- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- “Don’t Fall in Love With the Enemy” — Japanese Women POWs Warned, Kindness Followed. VD

“Don’t Fall in Love With the Enemy” — Japanese Women POWs Warned, Kindness Followed. VD

“Don’t Fall in Love With the Enemy” — Japanese Women POWs Warned, Kindness Followed

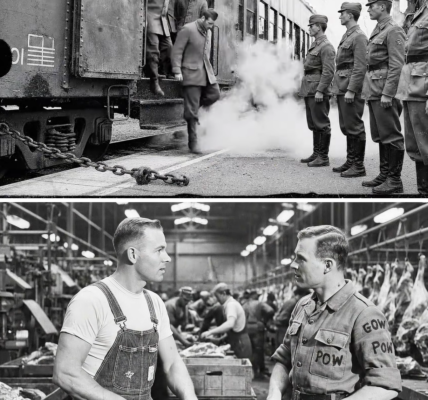

In the Shadow of War

The sun beat down relentlessly on the Texas desert as Ko Tanaka, a 20-year-old Japanese translator, sat silently in the back of a military truck. It was August, and the dry heat seeped into her skin like a thousand needles. The metal beneath her burned through her thin cotton dress, and each breath felt as if the very air was being stolen from her lungs. The convoy was heading to an American internment camp, and with every mile, Ko’s heart raced faster, her grip on the metal rail beside her tightening as if it could somehow hold her together.

Ko wasn’t alone. Surrounding her were 42 other women—nurses, radio operators, clerks—each one a prisoner, captured in the final chaotic days of the war. They had all been raised on the same terrifying stories of American cruelty. Propaganda films had painted the enemy as monstrous, merciless creatures with no regard for the lives of their captives, especially the women. But as the truck rumbled on, Ko’s mind kept replaying her mother’s final, desperate words: “If the Americans capture you, take your own life. Death is better than dishonor.”

A razor blade had been sewn into the sleeve of Ko’s dress, a silent insurance policy against the fate that awaited them. She could feel its cold presence pressing against her skin, a reminder that, in her mind, death was the only escape from dishonor.

The truck finally slowed, and through the canvas covering, Ko could see the shadow of watchtowers rising against the impossibly blue Texas sky. The gate loomed ahead, its barbed wire flashing in the sunlight like the cruel smile of an executioner. This was it. The moment they’d all been dreading.

As the truck came to a stop, Ko’s heart hammered in her chest. The boots of American soldiers could be heard crunching on the gravel, and their harsh, guttural language filled the air. Her breath caught in her throat as her body tensed, preparing for the worst. But when the truck’s canvas flap was pulled back, revealing the soldiers outside, Ko’s world tilted.

The men were not the demons she had imagined. They were young, just boys really, standing in loose circles, helmets tucked under their arms. They didn’t seem like monsters—they seemed confused. Their faces betrayed uncertainty and discomfort, not the violence she’d been warned about. There was no cruelty in their eyes, no hunger for brutality, just the quiet unease of men who weren’t sure what to do with a group of defeated women.

One soldier stepped forward. His red hair caught fire in the sunlight, and freckles dotted his face. He couldn’t have been older than 25. Ko watched as he cleared his throat and spoke in a voice far softer than she had expected.

“Ladies,” he said, pausing as if unsure of what to say next, “You are now prisoners of war under the authority of the United States Army. You will be processed, given medical examinations, and assigned quarters. You will be treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.”

The words barely registered in Ko’s mind. The women around her remained silent, staring at the ground in fear. They had been taught to expect nothing but cruelty. But Ko’s father, a professor of literature, had taught her English in secret. And so, when the sergeant asked if anyone spoke the language, Ko’s hand rose, trembling, but resolute.

“I speak a little English,” she whispered.

The sergeant’s face brightened with relief, and he gestured for her to step down from the truck. As Ko hesitated, he reached up and helped her down, his grip firm but gentle. She expected his hands to be rough, to grab her, but instead, they were steady, almost tender. There was no violence in his touch, only a strange care that made her stomach twist in confusion.

The sergeant introduced himself as Buck Thompson, and as he led them toward the camp, Ko’s mind raced. She had expected brutality, torture. But what she saw was nothing like that. The buildings were clean, orderly, and freshly painted. Gardens bloomed alongside barracks, and the soldiers, though armed, seemed relaxed, almost bored. There was no looming sense of danger. Only calm, routine.

But it was when they were led into the mess hall that the enormity of what was happening truly hit Ko. The food laid out before them—real food, hot and abundant—was beyond anything she could have imagined. She had not tasted a proper meal in months, and the sight of it almost broke her. There was rice, perfectly cooked chicken, vegetables, cornbread, and even fresh peaches. It was a meal that spoke of comfort, of abundance, of a nation that could afford to feed its enemies like honored guests.

Ko’s hand trembled as she took the tray. The American soldier who served her, Private Martinez, smiled at her. “Enjoy, ma’am,” he said, his voice kind and genuine.

Ma’am. Ko could not remember the last time anyone had addressed her with such respect. She carried the heavy tray to a table, her mind reeling. These soldiers, these Americans, had been painted as monsters. But here they were, feeding her like a human being, like a person of value. The contradiction was too much to process, and Ko sat there, staring at her food, unable to understand the world around her.

Fumiko Yamamoto, the eldest among them, leaned over and whispered in Ko’s ear, “Don’t trust them. This is a trap.”

But the hunger was too great. Slowly, the other women began to eat, tentatively at first, but with growing desperation. The food tasted like life, like survival. Ko took a bite of chicken, and the flavor exploded in her mouth, rich and smoky, so tender it fell apart on her tongue. She had forgotten what it was like to eat with joy.

In the days that followed, Ko worked alongside the soldiers, translating and helping the women understand their new reality. But every time she looked into the eyes of the men, she saw something that didn’t align with the stories she had been told. They were human, just like her, trying to survive in a world that had been torn apart by war.

Sergeant Thompson, in particular, seemed different. He treated Ko with respect, with care. There was no hatred in his eyes, no malice in his words. He was simply a young man, doing a job, trying to navigate a world that had become irreparably broken. Ko found herself drawn to his humanity, to the quiet kindness he showed even as they both lived through the rubble of war.

And in those quiet moments, Ko began to understand the true cost of war. It wasn’t just the loss of life or the destruction of cities—it was the loss of humanity. Both sides had been dehumanized by their leaders, by the propaganda that taught them to hate. But here, in the mess hall, in the library, in the small exchanges between prisoners and guards, humanity found a way to survive. And perhaps, just perhaps, that was the first step toward healing.

Ko would never forget the lessons she learned at Crystal City. They were not the lessons of war she had been taught as a child, but the lessons of kindness, of truth, of the complexity of human nature. In those moments, she learned that even enemies could become friends, that the greatest strength lay in choosing humanity over hatred.

And as the camp doors closed behind her, and the journey back to Japan began, Ko knew that she was not the same person who had stepped onto that truck months ago. She was someone different, someone who had seen the world not as black and white, but as a tapestry of contradictions, of kindness and cruelty, of strength and vulnerability.

Ko Tanaka’s story is a reminder that even in the darkest times, even in the worst of circumstances, humanity can still shine through. And it is through kindness, through understanding, that we can begin to heal the wounds of war.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.