Cheating Death: They sent him to die, but he danced through a storm of German lead like it was a sunny afternoon. NU

Cheating Death: They sent him to die, but he danced through a storm of German lead like it was a sunny afternoon

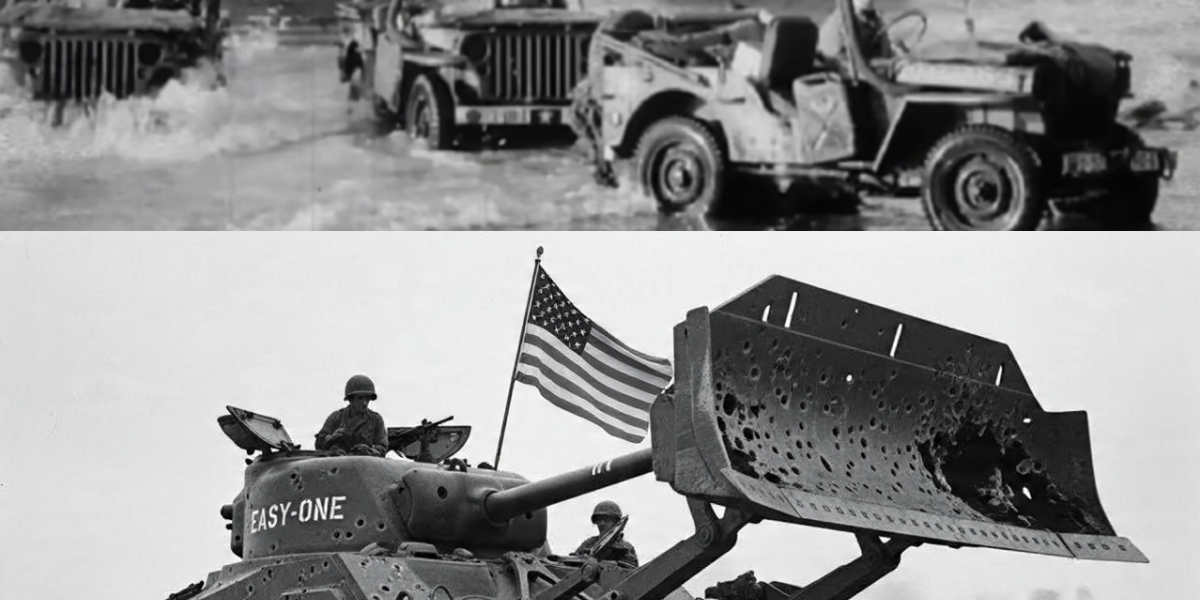

The morning of June 6, 1944, did not begin with glory for Private Vinton Dove. It began with the smell of diesel, vomit, and the metallic tang of salt air. At 7:30 a.m., the 24-year-old construction worker from Virginia was crouched behind the steel-plated cab of a Caterpillar D8 bulldozer, watching the cold Atlantic waves wash over the corpses of the fifth assault wave at Omaha Beach.

Dove had exactly two months of bulldozer training and zero minutes of combat experience. His commanding officer in Company C of the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion had been blunt: the survival rate for dozer operators was less than 20%. The engineers called it a “suicide mission.”

The German 352nd Infantry Division had turned Exit Easy-1 into a vertical killing field. Seventeen machine-gun nests, four anti-tank guns, and pre-registered mortar coordinates had trapped 4,000 American soldiers behind an eight-foot wall of shingle stones. If the bulldozers couldn’t clear a path for the tanks and supply trucks, the invasion of Omaha Beach would fail by lunch.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF A MASSACRE

The plan had been flawless on paper. Heavy bombers were supposed to level the German bunkers. Navy destroyers were supposed to suppress the artillery. Duplex Drive (DD) Sherman tanks were supposed to swim ashore to provide cover.

The reality was a disaster.

-

The Bombers: Released too late due to cloud cover; all 1,300 tons of bombs landed three miles inland.

-

The Tanks: 27 of 32 tanks sank in the six-foot swells.

-

The Navy: Shelling was too brief; German gunners remained untouched in their concrete casemates.

Dove drove his dozer into neck-deep water at 07:28. The waterproofed engine coughed, roared, and bit into the sand. As the ramp dropped, Dove saw two other bulldozers already burning at the waterline. He was the last operational dozer in the eastern sector.

THE SATURDAY AFTERNOON BLUFF

German gunners realized the bulldozer was the most dangerous weapon on the beach. They concentrated every weapon they had on Dove’s machine. Bullets sparked off the blade in continuous, blinding streams. Dove couldn’t raise the blade without exposing himself, and he couldn’t lower it without losing visibility. He kept the blade at chest height and drove blind.

At 08:00, he hit the shingle bank. The dozer bucked like a wild horse. Stones the size of grapefruits cascaded over the hood. Dove throttled up, the engine screaming as the tracks finally found purchase.

He created a gap five feet wide. Then twelve feet. Then twenty. Every German mortar observer within 400 yards began walking shells toward his position. Dove and his relief operator, Private William Shoemaker, began a lethal dance, switching seats every twenty minutes to keep the machine moving.

Watching from five miles offshore on the cruiser USS Augusta, General Omar Bradley lowered his binoculars. He saw the carnage on Omaha and turned to his staff, preparing to order a full evacuation. Then, he spotted something through the smoke: a single bulldozer on the eastern flank, moving stones as if it were a “Saturday afternoon back home.”

“I’ll never forget it,” Bradley later wrote. “Like they were plowing a driveway while the world exploded.”

THE BREAKDOWN IN THE KILL ZONE

At 08:47, disaster struck. A German machine-gun burst stitched across the right track housing. Three track links sheared completely. The track separated, the dozer lurched, and the engine stalled.

Dove and Shoemaker were now sitting ducks, half-in and half-out of a 9-foot-deep anti-tank ditch. To stay was to die. To run back for cover was to abandon the only exit for 4,000 men.

Dove ran. Not for cover, but for a crowbar.

Under a curtain of tracers that whined inches above his helmet, Dove levered the broken track back onto its sprocket. He didn’t have a maintenance tent or four hours. He had a rusted bar and thirty seconds.

Shoemaker hit the starter. The Merlin-inspired engine coughed black smoke, caught, and roared. The tracks bit. The dozer lurched forward out of the ditch. At 09:14, they resumed their work.

THE STATISTICAL ANOMALY

By 10:32 a.m., the first Sherman tank rolled through the gap Dove had carved. By noon, 3,000 vehicles had followed. Exit Easy-1 became the principal artery of the Omaha invasion.

Dove sat on the back of his broken machine, his hands finally beginning to shake. He had been under direct fire for three hours and twenty-six minutes.

Decades later, a military researcher at the Army War College analyzed the data from Exit Easy-1. German after-action reports confirmed that the strongpoint had fired over 23,000 rounds at Dove’s position. Statistically, Dove’s probability of survival was calculated at 0.003%.

The researcher labeled it a “statistical outlier that defied mathematical modeling.” Something outside the parameters of physics had intervened.

THE MODESTY OF A GIANT

General Bradley recommended both Dove and Shoemaker for the Medal of Honor. However, the recommendation was downgraded by General Eisenhower to the Distinguished Service Cross. No official reason was given, though rumors suggested Eisenhower didn’t want to award the highest honor for “engineering work.”

Vinton Dove returned to Virginia in 1945. He went back to work in construction, operating bulldozers for 38 more years. He never joined veterans’ groups. He never marched in parades. He kept his Distinguished Service Cross in a dresser drawer, under a stack of socks.

When his son asked him why he never spoke about D-Day, Dove’s response was always the same: “I wasn’t a hero. The heroes are still on the beach. I just did what I was told. I was lucky I made it across.”

EPILOGUE: THE BLADE IN THE MUSEUM

Vinton Dove died in 2003 at the age of 83. Shortly before his death, he donated his uniform and medal to the Engineer Museum at Fort Leonard Wood.

The centerpiece of the exhibit is a section of the actual bulldozer blade recovered from Omaha Beach in 2002. It is rusted and pitted, but if you look closely, you can still see the indentations of German bullets.

The museum placard doesn’t mention the “0.003% survival rate.” It doesn’t mention the “statistical impossibility.” It simply tells the story of a private who worked a machine like it was a Saturday afternoon—and in doing so, ensured that the thousands of men behind him would live to see Sunday morning.

The beach at Exit Easy-1 is now a peaceful paved road. Tourists drive over it every day, unaware that the ground beneath them was once cleared by a man who refused to believe the math of his own death.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.