“Books for the Enemy?” — Why American Libraries Stunned Japanese POW Women

Seeds of Mercy

A Prisoner’s Choice

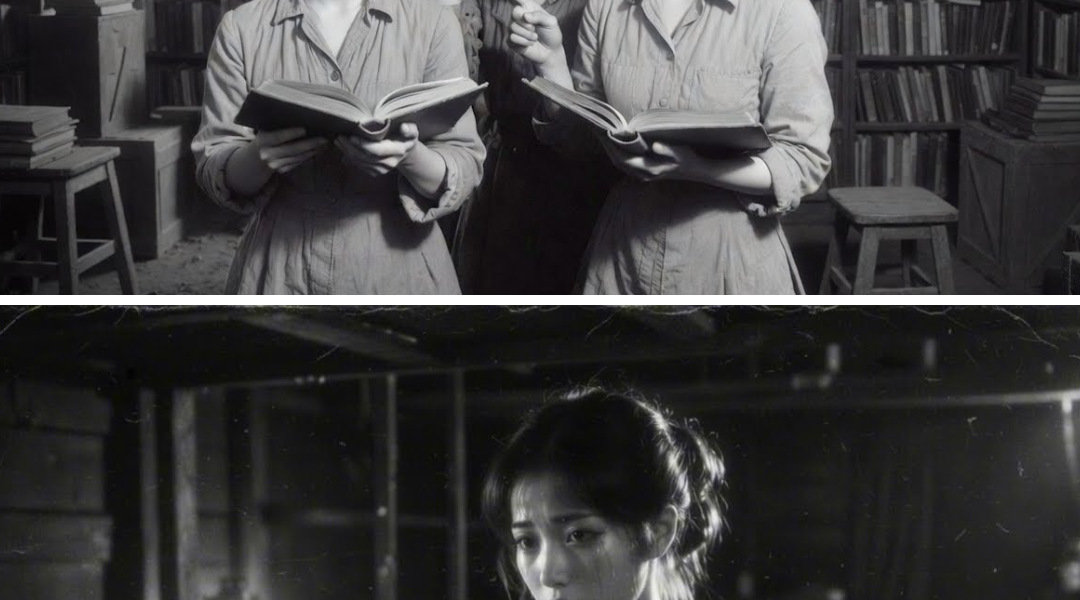

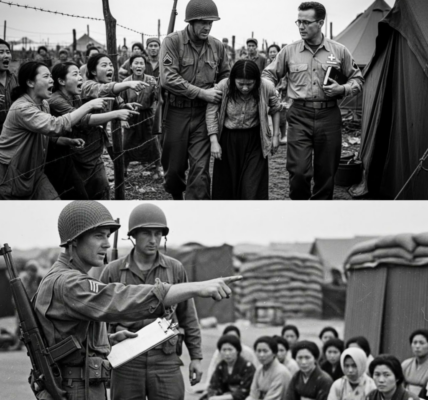

Sachiko Tanaka’s fingers hovered over the shelf. It was January 1945, and she was in a Texas prisoner of war camp, a far cry from the battlefields of Okinawa and Saipan, where she had once fought alongside her countrymen. But now, she was a prisoner, caught in the net of defeat, surrounded by women who shared her shame and fear. She had been raised to believe that surrender was dishonorable, that enemies were demons to be destroyed, not helped. Yet here she was, staring at a bookshelf, the very symbol of knowledge that she had been taught to fear.

The library was small, tucked away in a corner of the camp. Its dusty air smelled of old leather and paper, an unfamiliar, almost surreal scent after the constant stench of war. The room was quiet, save for the gentle hum of Mrs. Henderson, the camp librarian. She was a woman who had seen enough hardship herself, her own son lost to Japanese artillery just weeks before Sachiko’s arrival.

Sachiko had been prepared for cruelty. She had been taught that American soldiers were brutal, unmerciful. Yet, in front of her stood a woman who greeted her with a warm smile and offered her the freedom to choose a book from the shelves. No interrogation. No threats. Just a simple offer of knowledge.

“Take your time, honey. Any book you want,” Mrs. Henderson said, her Southern drawl carrying the warmth of kindness, a kindness Sachiko had been told was impossible in the enemy.

The Conflict of Survival

For years, Sachiko had carried the burden of survival. She had been taught that death was preferable to capture, that the enemy’s brutality knew no bounds. She had volunteered as a nurse for the Japanese army, believing she was helping her country, fighting for a righteous cause. But now that the war had ended in defeat, her survival felt like a betrayal. Her brother Teeshi had died fighting for the emperor’s honor, and their father had perished in the ruins of Hiroshima. To her, survival had become a silent shame.

The food they had been given was strange. Real bacon, eggs, butter, and coffee—luxuries she had not tasted in years. The Americans had given them these things, despite the pain and suffering Japan had inflicted on them. The nurse, Dr. David Walsh, had treated her with a kindness she had never expected. He had called her skilled, not a prisoner of war, but a person who could still be useful.

Now, in front of her, stood the librarian, offering books in her own language. The idea of reading felt foreign, almost like an act of defiance. How could she choose a book, something that represented the enemy’s culture, their way of life? She had been taught that Japan’s way was the only way, that their destiny was set in stone. But here, the idea of survival was not just about the body—it was about the mind.

The Key to Understanding

As Sachiko reached for the book, her hand trembled. She pulled back, then reached again, touching the spine of “The Secret Garden.” The cover was familiar—green cloth, faded from use, but it was the same book her mother had read to her when she was a child, before the war, before the devastation. Her mother had loved that book, and now, in this strange land, it felt like the last piece of her lost past.

Mrs. Henderson noticed her hesitation. “That’s a good one,” she said, her voice gentle. “I read it when I was little. You like gardens?”

Sachiko could hardly believe what she was hearing. Gardens? She had not seen a garden in years. She had seen fields turned to ash, cities burned to the ground, and the faces of the dying on every battlefield. But here, in the library, she was being offered something pure, something untouched by war.

It was too much. Too simple. Too kind.

A Moment of Mercy

With shaking hands, Sachiko took the book. She wrapped it in her jacket, careful not to let anyone see it. Tomoko, the leader of the resistance group in the camp, would never understand. Tomoko had always preached that survival was dishonorable, that accepting American kindness was an act of betrayal. But Sachiko couldn’t shake the feeling that this kindness was different. It was not manipulation. It was real.

That night, after the camp lights had dimmed and the women lay in their bunks, Sachiko opened the book. She read the first lines and felt the tears rise. It wasn’t the story of a garden, or a young girl finding her way. It was a story about renewal, about growth in the most unlikely places. It was the story of a secret garden hidden behind a locked door, just like her heart had been locked away by the walls of war and shame.

Mary Lennox, the orphaned girl in the story, found life in a garden that had been neglected, left to die. Sachiko saw herself in that garden, a woman who had been taught to die for a cause, but who now had to choose something different: to live for the truth.

The Library’s Legacy

Three weeks later, Sachiko returned to the library. She stood in front of Mrs. Henderson, her English improving, her heart heavier with the weight of what she had learned. Mrs. Henderson smiled when she saw her. “Finished already? My goodness, you’re a fast reader,” she said warmly.

Sachiko nodded, her mind still swirling with the implications of the story. “It’s beautiful. Thank you,” she said, her voice soft, filled with gratitude.

Mrs. Henderson’s eyes lit up. “Well, if you’re serious about learning, honey, I’ve got someone I want you to meet.”

That someone was Miss Sarah Roberts, a school teacher from Austin who had volunteered to teach English to the prisoners. Sarah’s bright enthusiasm was infectious, and under her guidance, Sachiko and the other women began to learn more than just the language of their captors. They learned about the world beyond their war, about democracy, freedom, and the power of education.

The more Sachiko learned, the more she began to question the lies she had been taught. The war had turned everything she knew into dust. The Emperor’s divine rule, the honor of battle, the unquestioned loyalty to the cause—all of it had been shattered. But in the library, Sachiko found something stronger than propaganda. She found truth. She found hope. And she found that, even in the darkest of times, kindness could still exist.

The Final Lesson

In late November, Mrs. Henderson gave Sachiko a final gift—”The Secret Garden” in a new copy, and an English-Japanese medical dictionary, along with a notebook and a pen set. “When Japan gets libraries again,” Mrs. Henderson said, “you find these books, you keep learning, you keep growing.”

Sachiko was overwhelmed. She held the gifts in her hands, unsure of how to express her gratitude. “I will treasure this always,” she said.

The war ended in August 1945, but for Sachiko, the real battle had just begun. She was still a prisoner, still caught between two worlds—the one she had left behind in Japan and the one she was beginning to understand in America. But now, she had a mission. She had learned that survival could be more than just a matter of living. It could be about healing, about teaching, about finding peace in the middle of war.

By January 1946, the women were ready to return to Japan. But the journey back was not just about physical distance—it was about spiritual transformation. Sachiko had learned that survival did not mean living in shame. It meant living with truth. And that truth was the seed of the garden she would carry home with her.

A Gift of Peace

When Sachiko finally returned to Japan, it was not the country she had left behind. The cities were in ruins, the people were starving, and the trauma of war was still fresh. But even in the midst of the destruction, Sachiko carried the lessons she had learned in America. She found work as a nurse, teaching others the things she had learned about healing, about mercy, about what it meant to truly live.

One day, she stood in front of a classroom of young nurses, teaching them about medical care and about the importance of communication with patients. She shared the lessons from Mrs. Henderson’s library—the importance of reading, the importance of questioning what they had been told, and the importance of kindness in healing.

And when one of her students asked where she had learned to teach in such a way, Sachiko smiled softly and said, “I learned from Americans. From a librarian who gave me a book when I thought survival meant shame. I learned that even in the darkest of times, there is always room for kindness.”

The legacy of that small library in Texas, of a woman who had lost her son and chose mercy over grief, lived on in Sachiko. She passed it on to her students, to her children, to her country. And in doing so, she planted the seeds of change, a garden that would continue to grow for generations to come.

In the end, the lesson was simple: the strongest nations are not the ones that dominate through force. They are the ones that lead by example. And sometimes, the most powerful weapon is not the one that destroys, but the one that heals.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.