Beyond Endurance: A German woman’s collapse changed the rules of the gulag forever. NU.

Beyond Endurance: A German woman’s collapse changed the rules of the gulag forever

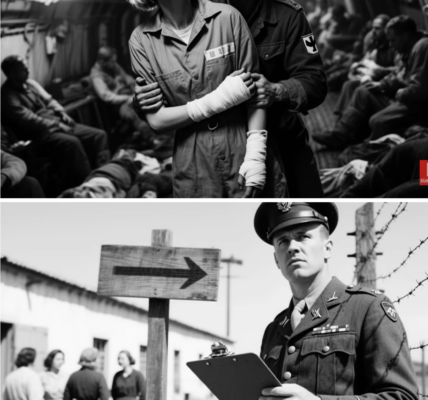

March 21st, 1945. A muddy forest clearing west of the Rhine. The air smells of wet pine, churned earth, and the lingering ghost of cordite. For Anelise Schmidt, a 21-year-old Signals auxiliary with the 53rd Signals Battalion, the world has shrunk to this cold, dripping patch of German soil. The frantic chatter of the MG42 has fallen silent. The final desperate crack of a Kar 98k rifle has faded, leaving an unnatural quiet broken only by the drip of water from skeletal branches and the distant, predatory rumble of engines. American engines.

Anelise’s fingers, numb and blue, are clenched around the strap of her headset—a useless relic of a command structure that no longer exists. Just hours ago, she was relaying coordinates, her voice a calm, professional monotone amidst the chaos as Hauptmann Richter tried to rally the remnants of their unit. Now, the Hauptmann lies near a shattered oak, his face turned toward a pitiless gray sky. The others are scattered—dead, wounded, or melting back into the woods. Anelise and a handful of others are all that remain. They are trapped.

The rumble grows louder. It is not just a sound; it is a physical pressure, a vibration that travels through the soles of her worn leather boots and into her bones. Then they appear, emerging from the misty treeline like steel behemoths: the Sherman tanks of the US 3rd Armored Division. Their turrets traverse slowly, menacingly.

Behind them, infantrymen spread out in a loose skirmish line, M1 Garands held at the ready. Their movements are fluid, economical, terrifyingly competent. They are not the exhausted, desperate soldiers of the Wehrmacht; they are hunters who have cornered their prey.

Anelise’s training, her discipline, the years of propaganda—it all evaporates in a cold wave of primal fear. A young corporal next to her, a boy named Dieter with fresh acne on his cheeks, makes a move to raise his rifle. An older Feldwebel—a sergeant with eyes that have seen Poland and Russia—slams the boy’s weapon down.

“Nein,” the old soldier rasps. “Es ist vorbei.” It is over.

A voice amplified by a bullhorn cuts through the tension. The meaning is unmistakable. “Drop your weapons. Put your hands on your heads. Hände hoch!”

One by one, the rifles clatter onto the wet leaves—the sound of finality. Anelise unplugs her headset and lets the apparatus fall. She raises her hands, palms open. She feels a hundred pairs of eyes on her. When a young private with tired blue eyes approaches her, he hesitates. He sees a woman in a grey-wool uniform, the lightning bolt insignia of the Nachrichtenhelferin on her sleeve. He motions with his rifle. “Hands up. Keep ’em up.”

She is a soldier, a prisoner, an enemy. The distinction no longer matters.

I. The Journey to the Cage

The journey is a blur of diesel fumes and suffocating twilight. Anelise is crammed into the back of a GMC truck, pressed shoulder-to-shoulder with men whose faces are masks of hollow-eyed shock. The smell is overpowering: sweat, fear, wet wool, and the metallic tang of blood. Through a gap in the canvas, she sees her homeland in ruins—villages turned to rubble, fields cratered by artillery.

When the convoy finally halts, harsh daylight floods the truck. Anelise stumbles out, her legs stiff, and sees a sea of tens of thousands of men. This isn’t a battalion; this is the death of an army.

The processing line is a lesson in dehumanization. A sergeant with a clipboard barely looks at her. “Schmidt, Anelise. Oberhelferin, 53rd Signals.” Her pockets are emptied: a photograph of her family in Dresden, a half-eaten bar of Ersatz chocolate, and a worn copy of Goethe’s poems. A corporal confiscates her pocket knife and pushes the rest back.

She is marched deeper into the burgeoning camp. There are no barracks, no buildings—nothing but a huge expanse of muddy farmland enclosed by towering fences of barbed wire. This is to be their home.

II. The Rheinwiesenlager

The place is officially designated Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosure A2. To the Germans, it is simply the Rheinwiesenlager—the Rhine Meadow Camp near Remagen. It is a holding pen carved from the waterlogged fields bordering the river. There is no shelter. The prisoners are expected to provide for themselves.

Anelise joins a small contingent of female prisoners. A nurse named Clara, a veteran of the Eastern Front, becomes her mentor. “Find high ground,” Clara advises. “And dig. Use your hands, a piece of wood, anything. The nights are cold and the rain will not ask for your permission.”

Survival is reduced to the primitive. For two days, they scrape at the hard clay with their fingers to create a shallow depression—a dugout just deep enough to offer meager protection from the wind. This hole in the ground is their sanctuary. At night, they huddle together for warmth, the thin wool of their uniforms a poor defense against the bone-deep chill.

Days settle into a grim routine dictated by two events: the distribution of food and the roll call. Food is a thin, watery soup served once a day and a single slice of hard black bread. But it is the roll call—the Appell—that becomes the central pillar of their existence.

III. The Trial of the Appell

Twice a day, at dawn and dusk, the whistles blow. The prisoners must assemble in neat rows of ten and stand at attention while American sergeants count. It is an exercise in control, a demonstration of power. But for the prisoners, it is a test of will. To stand straight, to hold your head high, is a declaration that you are not yet broken.

Collapsing during Appell is the ultimate sign of weakness. It draws the attention of guards who view it as either insubordination or a prelude to disease. The sick are taken to an infirmary tent on the edge of the camp, a place shrouded in rumor and fear. Few ever return.

So they stand. In the freezing rain. In the biting wind. For Anelise, the first few roll calls are a torture of muscles and bone. She focuses on the straightness of Clara’s spine and draws strength from it. She forces her mind to go blank, thinking only of the command: Stand.

By the third week of April, the camp has become a quagmire. The internal erosion is far worse than the physical. Hope is a finite resource. Anelise dreams of her mother’s cooking—roast pork and warm apple strudel—only to wake with tears on her cheeks and the bitter taste of mud in her mouth.

Clara remains her anchor. “Do not think of the whole day,” Clara rasps. “Think only of the next step: getting up, standing for the count, eating your bread. One step, then the next.”

IV. The Breaking Point

One morning, the whistle for roll call is a physical assault. Anelise lies in the damp dugout, her body refusing to move. Every joint aches; her head throbs with the drumbeat of misery.

“Anelise, it is time,” Clara’s voice is firm.

Getting up is an act of supreme will. A wave of vertigo hits her so hard she has to press her forehead against the muddy wall. The world is a blurry, tilting mess. She stumbles out into the gray pre-dawn light. Thousands of gray figures move like ghosts through the mist.

As they stand in formation, Sergeant Miller begins the count. “Bauer, Helga… Hier. Dresner, Eva… Hier.”

Anelise focuses on a guard tower silhouetted against the sky. She tries to detach her mind, but her body will not be ignored. Her legs feel like lead, trembling uncontrollably. Her heart hammers against her ribs—a frantic, irregular rhythm. A cold sweat breaks out on her brow despite the chill.

The sergeant’s voice is getting closer. She can feel the blood draining from her face. This is no longer discipline; it is a physiological battle, and she is losing. Her will is a fortress, but the walls are crumbling. She thinks of her mother’s face. I must stand for her. I must stand.

“Schmidt, Anelise!”

The sergeant’s voice cuts through the fog. It is her turn. She opens her mouth to form the simple, defiant word: Hier.

But no sound comes out. Her throat is tight, her tongue thick. All remaining energy is focused on the impossible task of remaining upright. Her vision tunnels. The guard tower, the faces, the gray sky—it all dissolves into a swirling vortex of black.

A final, desperate thought forms in her mind: “Ich kann không mehr stehen.” (I can’t stand anymore.)

Her body gives in before her will does. Her knees buckle first—a sudden, complete failure. There is no grace in the fall. She pitches forward like a marionette with its strings cut. She feels a brief, shocking sensation of weightlessness, and then the cold, wet slap of the mud as it rises to meet her.

A collective gasp ripples through the women around her. The last thing she registers is the sound of boots running on the wet ground and Clara’s frantic cry of her name.

Her battle to stand was over. The fight to simply live had entered its most desperate chapter.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.