America Had No RUBBER in 1942 — So They Invented Synthetic Rubber From Oil

December 8th, 1941, Washington DC. The day after Pearl Harbor. While Americans absorb the shock of war, a handful of men in a war department conference room stare at a different kind of catastrophe. Not on a map, on a spreadsheet. The numbers are brutal. US military rubber stockpile, 600,000 tons.

Rubber needed for full mobilization, 800,000 tons per year. Natural rubber supply zero. Japan controls 90% of the world’s rubber plantations. Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, all occupied or about to be. America’s entire rubber supply just vanished overnight. A colonel speaks quietly. Gentlemen, we have enough rubber to fight for 7 months.

After that, every tank stops moving. Every aircraft stays grounded. Every vehicle sits idle. We can’t make tires. We can’t make hoses. We can’t make gaskets, belts, or seals. Without rubber, modern warfare is impossible. The room is silent. Then someone asks the question everyone’s thinking. Can we make rubber artificially? Another man shakes his head.

Germany’s been trying since 1933. Their synthetic rubber barely works. It cracks in cold weather. deteriorates in heat. We’re years behind them. Then we have seven months, the colonel says, to do what Germany couldn’t do in eight years. Or we lose the war without firing a shot. This is the documented story of how America faced total rubber collapse in 1942.

How a handful of chemists racing against time created synthetic rubber from petroleum. and how that desperate gamble became one of the most important industrial achievements in history. But first, we need to understand what made natural rubber irreplaceable and why everyone thought synthetic rubber was impossible. The rubber problem.

Rubber comes from trees. Specifically, Ha Brasilianis, the rubber tree native to the Amazon. Workers cut the bark in diagonal slashes. White latex oozes out, collected in cups. The liquid is processed, smoked, and dried into raw rubber. The process hasn’t changed fundamentally in centuries. What changed was scale.

In 1900, the world used 50,000 tons of rubber annually. By 1940, 1.4 million tons. Almost all of it came from Southeast Asian plantations. British Malaya produced 40% of global supply. Dutch East Indies produced 35%. French Indo-China produced 8%. Thailand, Salon and Sarowak produced the rest. This concentration created a strategic vulnerability.

Whoever controlled Southeast Asia controlled rubber and in December 1941, Japan seized it all. The American auto industry consumed 450,000 tons of rubber annually. Military mobilization would require double that. One B7 bomber contained over 1,000 lb of rubber in tires, hoses, gaskets, and seals. One tank used 1,200 lb.

One battleship required 75 tons. A single jeep needed 32 lb just for tires. Multiply across millions of vehicles, and the numbers become staggering. Without rubber, mechanized warfare stops. period. President Roosevelt understood immediately. On December 19th, 1941, 11 days after Pearl Harbor, he established the Rubber Reserve Company under the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

Mission: Acquire every scrap of rubber in America and find alternatives. Any alternatives? The stockpile inventory revealed the crisis. 600,000 tons total reserves. The military alone needed 800,000 tons per year. Civilian consumption, another 600,000. American needed 1.4 million tons annually and had access to zero production.

The mathematics were catastrophic. The German head start. Germany had faced this problem earlier. After World War I, the Versailles Treaty restricted German access to colonial resources, including rubber. In 1926, German chemist Fritz Hoffman at Bayer Laboratories synthesized the first practical artificial rubber called buuna from butadine and natrium/sodium.

The name became shorthand for synthetic rubber. By 1933, Nazi Germany prioritized synthetic rubber development. Hitler knew war was coming. He knew Germany would be blockaded. Rubber was strategic. IG Farbin, the massive German chemical conglomerate, built synthetic rubber plants.

By 1939, Germany produced 22,000 tons of Bunacsess annually. The Allies studied captured German rubber. The verdict was harsh. It worked barely. German Buna cracked at low temperatures, degraded rapidly in heat, performed poorly in aircraft tires and military applications, but it was better than nothing. Germany was eight years ahead of America in synthetic rubber research and their products still didn’t work well.

American chemical companies had experimented with synthetic rubber during the 1930s. Standard oil, DuPont, Goodyear, Firestone, US Rubber, Goodrich all conducted research. Results were disappointing. Natural rubber had properties synthetic versions couldn’t match. Elasticity, resilience, heat resistance, durability.

Every synthetic formula sacrificed something critical. The chemistry was understood theoretically. Rubber is a polymer, long chains of isoprene molecules. Natural rubber contains thousands of isoprene unitslinked together. The challenge was replicating that structure artificially. German Buna used butadyne instead of isoprne polymerized with styrene.

The resulting polymer resembled rubber but wasn’t identical. Close but not close enough for demanding applications. When war came, America faced a choice. Copy German formulas that barely worked or start from scratch and hope for breakthroughs. They chose both. In January 1942, the government created the Rubber Development Corporation.

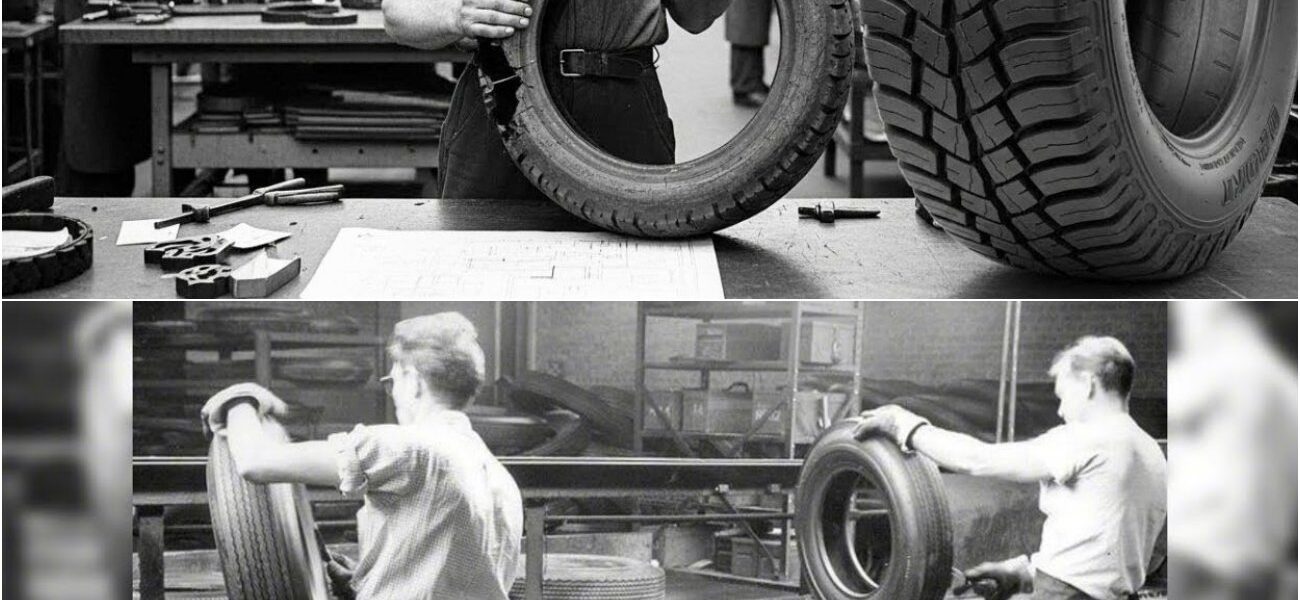

Director Jesse Jones, Commerce Secretary. Technical lead, Bradley Dwey, chemical engineer. Their mandate, produce 800,000 tons of synthetic rubber per year. By 1943, 18 months to build an industry that didn’t exist using chemistry that didn’t work against a clock that couldn’t be stopped. The Crash Program. February 1942. Dwey assembled America’s top rubber chemists in Akran, Ohio, the heart of US topper.

Tire manufacturing representatives from every major company. Goodyear Firestone. Goodrich. US rubber. Dupont sent chemists. Standard oil sent petroleum engineers. Dao chemical sent polymer specialists. These men were competitors. Fierce competitors. They’d spent decades guarding proprietary secrets. Now Dwey told them everything changes.

Gentlemen, we’re facing extinction. I don’t care about patents. I don’t care about trade secrets. I don’t care about competitive advantages. We share everything. Every formula, every failure, every success or we lose. The companies agreed reluctantly at first, then desperately because the alternative was losing their country.

The technical challenges were staggering. Natural rubber comes from trees that took decades to cultivate. Synthetic rubber required petroleum feed stocks that had to be refined, processed, and polymerized through complex chemical reactions. The process chain looked like this. crude oil, refining, buddyene extraction, polymerization, rubber production.

Each step required specialized facilities that didn’t exist. Building one plant would take years. They needed dozens. In months, April 1942, the government authorized $700 million for synthetic rubber plants, equivalent to 12 billion today. $50 one plants to be built simultaneously across the country. Butadyen facilities in Texas, Louisiana, West Virginia.

Polymerization plants in Ohio, New Jersey, Kentucky. Styrene production in Texas and Delaware. Carbon Black facilities in Louisiana and Oklahoma. The construction program rivaled Manhattan project in scale and urgency. But unlike atomic research, this was public. Everyone knew about it. The pressure was immense. Engineers worked around the clock designing facilities.

Construction crews broke ground before designs were finalized. Equipment was ordered before buildings existed to house it. Normal construction sequencing collapsed. They built and designed simultaneously. In Baytown, Texas, a butime plant went from groundbreaking to production in 11 months, normally 3 years minimum. In Institute, West Virginia, a styrenebutadian facility was producing rubber 13 months after construction started.

Industry veterans called it impossible. Then watched it happen. The chemistry problem. While construction raced forward, chemists faced the harder problem, making synthetic rubber that actually worked. German bunaw was the baseline. butadyne styrene c-olymer 75% butadine 25% styrene the Germans had proven it was possible but possible wasn’t good enough military specifications required rubber that performed across extreme temperature ranges -40° F to 250° F that resisted oils fuels and chemicals that maintained elasticity under stress that lasted years, not months. German

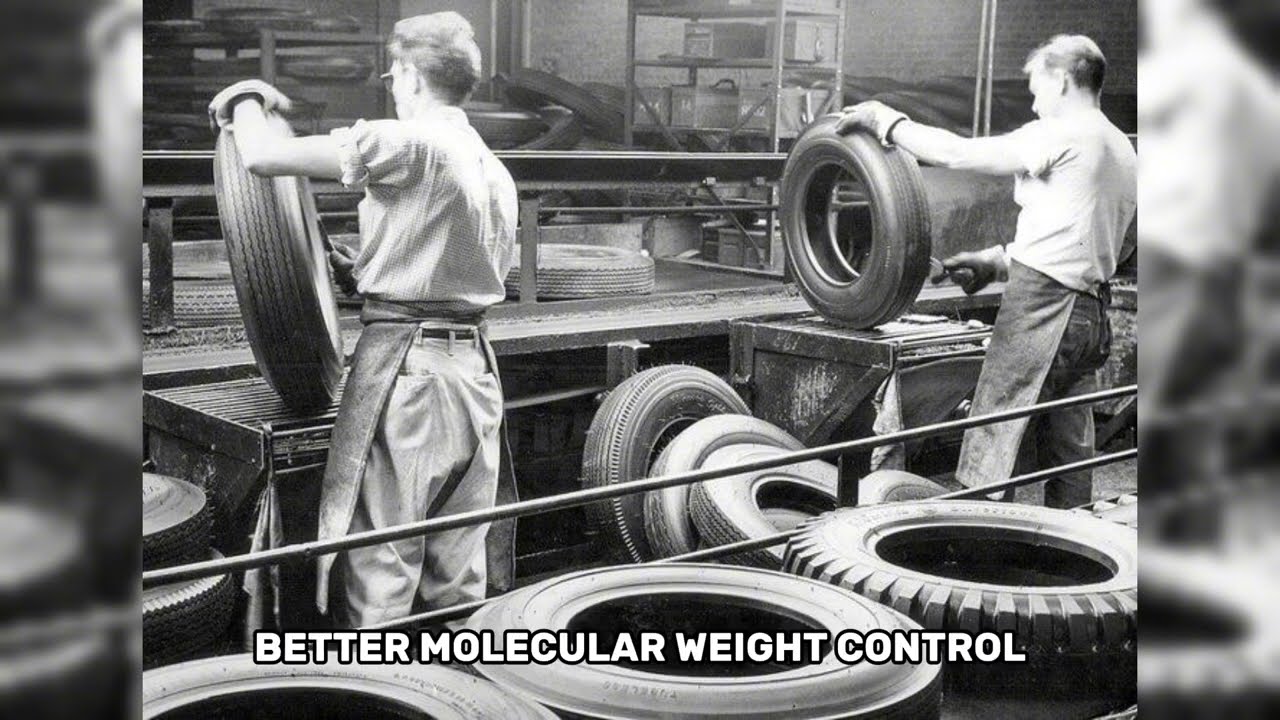

Buna failed most of these requirements. The breakthrough came from multiple sources simultaneously. Standard oil researchers modified the polymerization process controlling temperature and pressure more precisely. Dupont chemists discovered that adding small amounts of modifiers, fatty acids, and recaptins improved molecular weight control.

Goodyear researchers found that changing the ratio of butadion to styrene from 7525 to 7723 dramatically improved low temperature performance. Goodrich scientists developed better vulcanization processes adding sulfur to cross-link polymer chains. These discoveries were shared immediately. No company hoarded breakthroughs.

Every improvement circulated through the entire program within days. Competitive advantage meant nothing if America lost. By June 1942, American chemists had created GRS, government rubber styrene. The formula was similar to German bunash, but with critical improvements, better molecular weight control, improved temperature stability, enhanced durability.

GRS still wasn’t as good as natural rubber, but it was close enough and it could be made from petroleum in America. Beyond enemy reach production, August 1942, the first synthetic rubber plants came online. Output 2500 tons per month. Target 67,000 tons per month. They weren’t even close.

The facilitiesworked technically, but scaling chemical production from laboratory to industrial scale revealed countless problems. Reactors plugged with polymer residue. Pipes corroded from chemical exposure. Valves failed under pressure. Temperature control systems couldn’t maintain precision across large volumes. Each failure meant shutdown, investigation, redesign, restart.

Meanwhile, the rubber stockpile dwindled. By September, reserves fell to 400,000 tons. Four months of supply remaining. The government instituted rationing. Civilian tire production halted completely. Automobile manufacturing stopped. Existing tires were recapped, recycled, rationed. A nationwide scrap rubber drive collected old tires, boots, hoses, anything rubber.

Citizens donated rubber goods patriotically. The campaign collected 450,000 tons of scrap. It helped, but scrap rubber was degraded. Useful for low-grade applications, but not military equipment. The synthetic plants had to work. October 1942. Production reached 8,000 tons per month. Still inadequate, engineers and chemists lived at the plants.

70our weeks became normal. They optimized every step. adjusted temperatures, modified catalysts, redesigned equipment on the fly. The learning curve was brutal, but production climbed 10,000 tons in November, 152,000 tons in December, 22,000 tons in January 1943. Then testing began. Military specifications required proof.

Could GRS rubber survive combat conditions? The Army tested tires on jeeps driven through desert heat and arctic cold. The Navy tested hoses and gaskets in ship’s engine rooms. The Air Force tested components in aircraft operating at 30,000 ft. Results varied. GRS performed adequately in most applications. Excellent in some, poor in others, but adequate was enough.

Natural rubber had been optimal. Synthetic was workable, and workable meant survival. The turning point. March 1943. Synthetic rubber production reached 50,000 tons per month. The crisis was easing. Not solved, but no longer existential. By June, 65,000 tons monthly. The plants were approaching target capacity.

By September, 70,000 tons. They’d done it. 18 months from 0 to 840,000 tons annually. more than pre-war natural rubber imports. The impossible had become real. But challenges remained. GRS still underperform natural rubber in critical applications. Aircraft tires, tank treads, high performance hoses. For these, chemists developed specialized variants.

GRRI used isoprne instead of butadyne more closely mimicking natural rubber. Neoprene, a DuPont development, resisted oils and heat better than any natural rubber. Rubber excelled in inner tubes and gaskets. American synthetic rubber wasn’t one product. It became a family of specialized polymers, each optimized for specific applications.

Better than trying to replace natural rubber with a single formula. The diversity provided flexibility natural rubber couldn’t match. By 1944, synthetic rubber production exceeded 1 million tons annually. America produced more synthetic rubber than the entire world had produced natural rubber in 1940. The scale was staggering.

51 plants running continuously, 75,000 workers, 20,000 tons of beautifying weekly, 5,000 tons of styrene. The supply chain stretched across the country. Texas oil fields provided crude. Louisiana refineries extracted butadine. Ohio plants polymerized rubber. Michigan factories molded tires. Each piece interconnected, disrupting any length threatened the entire system.

But no enemy could disrupt it. The plants were in America. Beyond bombing range, beyond submarine reach, the German collapse. While America built synthetic rubber capacity, Germany struggled. Allied bombing targeted German chemical plants relentlessly. IG Farbin’s facilities at Ludvik Sophen Leverkusen and Holes suffered repeated raids. Production collapsed.

By 1944, German synthetic rubber output had fallen 40% from peak levels. Worse, quality degraded. Desperate to maintain output, German chemists cut corners, reduced polymerization times, skipped quality controls. The resulting rubber was barely functional. German tanks shed tracks. Luftwafa aircraft had tire failures on landing.

Vehicles broke down from failed hoses and gaskets. The rubber crisis Hitler had feared in 1933 arrived in 1944. German logistics depended on horses more than vehicles by war’s end, partially because they ran out of rubber. The contrast was stark. America entered the war with no synthetic rubber industry and built one from scratch in 18 months.

Germany had an 8-year head start and lost their capacity through bombing and resource depletion. Superior American industrial capacity combined with shared technical knowledge and massive government investment achieved what German otterarchy could not. Postwar impact victory in Europe. May 1945. Victory in Japan. August 1945.

The war ended. But synthetic rubber production continued because everyone realized something remarkable. They’d created an industry that worked betterthan the natural version for many applications. Postwar synthetic rubber wasn’t a desperate substitute. It became the preferred material. By 1950, 50% of US rubber was synthetic. By 1960, 70%.

By 1970, 75%. Today, over 60% globally. Natural rubber remains optimal for certain applications. heavyduty tires, earthquake dampers, medical devices. But for most uses, synthetic rubber offers advantages. Consistency. Natural rubber varies by plantation, season, and processing. Synthetic rubber is chemically identical every batch.

Performance. Specialized synthetics outperform natural rubber in heat resistance, chemical resistance, or durability. Cost. Synthetic rubber prices are tied to petroleum. More stable and often cheaper than natural rubber. Supply security. Synthetic rubber can be produced anywhere with petroleum and chemical facilities.

No dependence on tropical plantations. The synthetic rubber industry created in 1942 exists today. Expanded, refined, global. The chemistry developed in desperate 18-month crash programs became the foundation for modern polymer science. Styrene butadian rubber SPR the descendant of GRS is the most widely produced synthetic rubber.

50% of all rubber tires are made from SPR. The formula is essentially unchanged from 1943. Polybutadene rubber developed during the war is the second most common used in tires, belts and hoses. Polyclloroprene, neoprene, polyisoprene, bud rubber, nitral rubber, all developed or refined during the World War II synthetic rubber program.

The hidden victory. Historians debate which factors won World War II. Industrial production, codereing, strategic bombing, nuclear weapons. But rarely do they discuss rubber. It’s boring, technical, unglamorous. Yet without synthetic rubber, America couldn’t have won, couldn’t have fielded millions of vehicles, couldn’t have sustained mechanized warfare across two oceans and four continents.

Every tank, every aircraft, every ship, every jeep depended on rubber. And in 1941, America had none. The numbers tell the story. Total synthetic rubber produced by America 1 1942 1 945 3.4 4 million tons. Vehicles equipped 2.6 million military vehicles, 300,000 aircraft, 4,000 ships, tires manufactured, 86 million.

Without synthetic rubber, these numbers would be impossible. The war would have been lost. Not through military defeat, but through industrial paralysis. compared to Germany. Total synthetic rubber production 21933 1 945 1.1 million tons over 12 years. America produced three times more in 4 years.

The disparity reflects industrial capacity but also something deeper. America’s willingness to share knowledge to prioritize national survival over corporate advantage. German synthetic rubber development was controlled by IG Farbin, a cartel protecting patents and profits. American development was collaborative, government-f funded, open. The difference was decisive.

The forgotten chemists. Names like Eisenhower and Patton are remembered. Names like Bradley Dwey and the thousands of chemists who created synthetic rubber are forgotten. Yet, their contribution was equally critical. Without generals, armies would lack leadership. Without rubber, armies wouldn’t move.

The chemists who worked one eight-hour days in Texas refineries deserve recognition. The engineers who built 51 plants in record time deserve remembrance. The workers who operated facilities under pressure deserve acknowledgement. They won no medals, fought no battles, but they won the war as surely as any soldier. One chemist interviewed after the war described the pressure.

We knew the entire war effort depended on us succeeding. Every day we failed meant soldiers died because equipment didn’t arrive. That knowledge drove us. We’d work until we collapsed, sleep 4 hours, and return. Not for patriotic speeches or propaganda because we understood the mathematics. No rubber equals no mobility equals defeat. It was that simple.

The modern legacy. Today, synthetic rubber is ubiquitous, invisible. Every car has 200 lb of rubber in tires, seals, hoses, and belts. Every aircraft uses thousands of rubber components. Every smartphone has rubber in shock absorption and ceiling. The modern world runs on rubber. 90% of it is synthetic.

Created from petroleum through processes developed in desperate 1942 crash programs. The technology has advanced. Modern catalysts improve polymerization efficiency. Computer modeling optimizes molecular structures. New formulas create rubbers with properties impossible in 1943. But the fundamental chemistry remains unchanged.

Polymerize butadine with styrene. Control molecular weight. Vulcanize with sulfur. The process American chemists perfected under wartime pressure. Still produces most of the world’s rubber. And the strategic lesson remains relevant. Control of natural resources creates vulnerabilities. Dependence on foreign supplies becomes liability during conflict.

The ability to synthesize critical materials from availableresources provides security. America learned this in 1942 when Japan sees rubber plantations. The response creating synthetic rubber from petroleum ensured it never happened again. Conclusion. The quiet revolution. December 1941, America faced rubber catastrophe. 7 months of supply, no natural sources.

Every expert said synthetic rubber couldn’t match natural performance. Germany had tried for 8 years and failed. America had 18 months or lose the war. They succeeded not through single genius breakthrough, through collaborative desperation, shared knowledge, massive investment, brutal work schedules, and fundamental chemistry that it turned out worked better than anyone expected.

By 1945, America produced more rubber than the world had ever seen. All synthetic, all from petroleum, all created in facilities that didn’t exist in 1941. The industry built under crisis became permanent, profitable, essential. Today, synthetic rubber is a 35 billion global industry employing hundreds of thousands, producing 15 million tons annually, all descending from desperate 1942 programs.

The lesson isn’t just technical, it’s philosophical. When catastrophe threatens, impossible becomes irrelevant. You do what’s necessary or perish. America in 1942 faced impossible chemistry, impossible timelines, impossible scale, and achieved all three because failure meant extinction. Success meant survival. And when those are the alternatives, people find ways.

The rubber crisis of 1942 forced innovation that changed the world. Not just winning the war, creating materials that enabled post-war prosperity, modern transportation, global commerce, technological advancement, all built on rubber, synthetic rubber made from oil, invented in 18 desperate months. Because America had no choice and succeeded beyond anyone’s imagination.

If this story of how desperate crisis created lasting innovation inspired you, hit that like button and subscribe. We bring you the forgotten technical achievements that shaped history, the unglamorous innovations that won wars, and the quiet revolutions that changed everything. More incredible documentaries coming your