America Copied Britain’s Nissen Hut — But Missed the One Thing That Made It Great

n the archives of military engineering, few designs were as brilliant or as misunderstood as the Nissen Hut. Conceived in the mud and chaos of 1916, it became Britain’s quiet weapon of endurance. Decades later, when America sought to replicate its success, the result was impressive, but not identical.

Because somewhere between adaptation and ambition, the US version lost the one principle that made Nissen’s creation a masterpiece of wartime design. When Major Peter Norman Nissen trudged through the mud of Northern France in 1916, he was not thinking about architectural fame. He was watching soldiers freeze to death. The Western Front was a graveyard of innovation.

Timber was scarce, canvas tents collapsed under snow, and every attempt to build lasting shelter was destroyed by artillery or exhaustion. Nissen, a Canadian-B born mining engineer serving with the Royal Engineers, saw something others overlooked. Stacks of unused corrugated iron sheets lying forgotten near supply depots.

Those thin curved panels meant for roofing were everywhere, rusting in the rain while men slept in the cold. He began sketching ideas in a solders’s notebook, drawing half circles and noting angles. The genius of his thought was not complexity, but brutal simplicity. What if the roof itself became the walls? What if strength came from the curve? Within a week, Nissan had built a crude prototype, a half cylinder of bent steel sheets joined at the seams, needing no beams or pillars to hold it up.

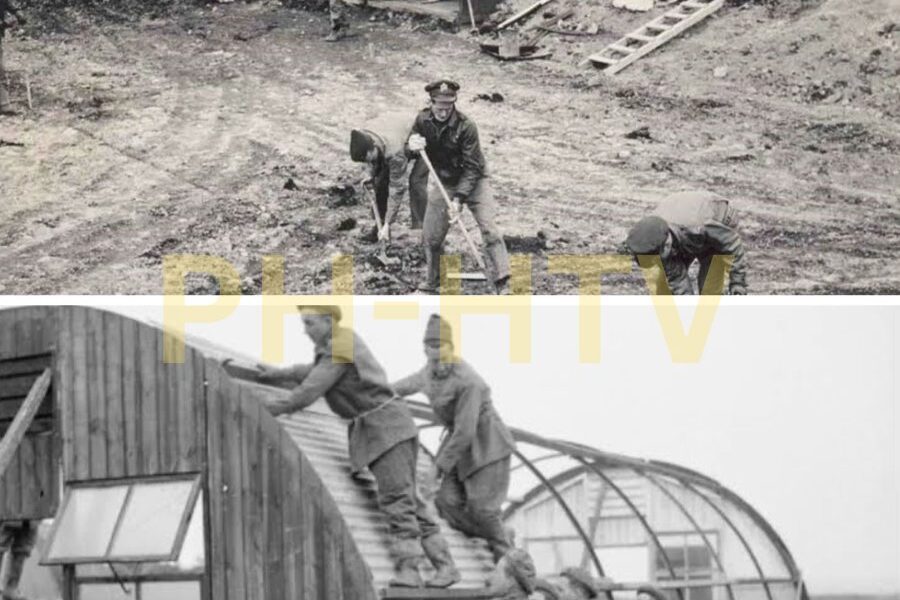

Six ordinary soldiers, none of them trained builders, erected it using only basic army tools. In less than four hours, a new kind of shelter stood against the wind. The design evolved quickly. Two more prototypes followed as Nissen refined dimensions and tested materials. The final version used pre-drilled corrugated sheets, perfectly spaced 14 in apart, so no measurement errors could delay construction.

Pre-fabricated wooden ends with doors and windows arrived, ready to bolt on. Even transport was solved. Nissen worked with three draftsmen to create foolproof packing diagrams showing how a complete hut could fit inside a three-tonon truck with space left for three men. Every element of his design was engineered for speed, precision, and common sense.

In March 1916, the British Army approved testing. At Richboroough Port, the 172N tunneling company assembled 20 huts in a matter of days. Officers were stunned. A shelter that could be packed, shipped, and built anywhere without architects, without carpenters, without delay. The War Office ordered 10,000 units before winter.

By the time the S offensive raged later that year, Nissen huts were rising behind the lines faster than trenches could be dug. For soldiers who had lived under canvas, the curved steel felt almost luxurious. The standard hut measured 16 ft wide and could house 30 men comfortably. The design’s strength lay in its geometry. The curve distributed stress evenly, so blast waves and shrapnel deflected harmlessly across the metal skin.

Vertical walls, the weak points of traditional buildings, no longer existed. Bolts overlapped three layers of corrugated iron, forming a continuous shell that resisted collapse even under nearby shellfire. Inside, conditions were basic but dry. Wooden floors kept the men off the damp ground. Adjustable vents at each end improved air flow and reduced condensation.

In the field hospitals near the sum, construction units erected Nissen huts under artillery fire to shelter the wounded. The huts could be placed on wooden sleepers, concrete, or directly on packed earth if the front demanded haste. With six men and a single day of work, they could build a home in no man’s land. By 1918, more than 100,000 nizen huts stood across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

They became the silent architecture of the British war effort. Barracks, supply depots, command posts, and field hospitals, all uniform, reliable, and unmistakably British. Each curved outline symbolized an empire’s ability to adapt under pressure. Soldiers joked that the huts could survive the war better than they could.

Peter Nissen never profited from his invention. As an active duty officer, he wasn’t entitled to payment. The War Office, however, recognized his contribution and allowed him to patent the design after the war ended. He returned to civilian life in 1919. A quiet man who had changed military engineering forever. When American engineers first studied the British Nissen Hut blueprints, they admired the elegance, but they also misunderstood it.

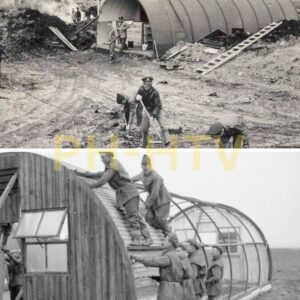

To them, the design looked too simple. the curved steel shell, the modular ribs, the minimal floor, it almost seemed primitive compared to America’s industrial construction standards of the early 1940s. So when the US Navy decided to create its own version in 1941, they didn’t copy it line by line. They redesigned it stronger, bigger, and heavier.

That redesign would become the Quonet Hut, named after Quanset PointNaval Air Station in Rhode Island, where the first prototypes were built in record time. Within just 60 days, the first production models rolled out. They were larger, typically 16x 36 ft, later expanded to 20x 48 ft with plywood ends, doors, and insulation.

They could be packed flat, shipped anywhere, and assembled by untrained soldiers. Over 150,000 were built by the end of the war. A staggering number that turned the Quonet Hut into a symbol of American logistical power. But for all that success, the Americans had missed what made the Nissen Hut great. The British version wasn’t just a shelter.

It was a masterpiece of efficiency. It used the fewest possible materials, minimized labor, and could be disassembled and moved in hours. Its secret lay in the perfect curvature of the shell, strong enough to resist snow and wind, but light enough to transport easily on muddy roads and wooden carts. The Americans, however, altered the curvature.

They made it wider and flatter to increase space. And in doing so, they lost the mathematical perfection that made the Nissen structure self-supporting. The result, the quantit was stronger on paper, but less efficient in the field. It required more materials, more insulation, and sometimes a foundation. Niss’s huts could stand almost anywhere.

Grass, dirt, even mud. Quanets needed preparation, and when mass deployment began across the Pacific, that difference became painfully clear. Still, the Quanet had its advantages. It was more comfortable, more versatile, and easily adapted for offices, hospitals, workshops, and barracks. For American troops landing in remote islands from Guadal Canal to Okinawa, the curved steel shelters became a familiar site.

They called them tin cans or half moons. But to many soldiers, they felt like a little piece of home in the middle of chaos. By 1944, entire bases and field hospitals were built from quonet huts alone. In Britain, soldiers continued to live in the original Nissen huts, simpler, cheaper, but colder. The Americans brought plywood, insulation, and even small stoves into theirs.

Different philosophies reflected in metal and wood. One born from necessity, the other from comfort. Yet even decades later, veterans and historians would agree the Nissen Hut’s design remained unmatched for sheer efficiency and portability. And though America’s Quonet became more famous, it was in truth a tribute to a forgotten British engineer who solved a problem no blueprint alone could measure, the speed of survival.

After the war, the Quanet Hut didn’t disappear, it multiplied. Across America’s returning bases, the curved shells were sold to civilians for a few hundred a piece. They became post-war homes, classrooms, churches, and repair shops. Even today, scattered across the Midwest and Pacific Islands, you can still spot their familiar half circle silhouettes, rusted but standing strong.

The Nissen Hut 2 lived on. In Britain, thousands were repurposed after 1945 as farms, stores, garages, and community halls. But while the Quonet became an American icon, Nissen’s name faded quietly into history. Few knew that the design that housed millions of soldiers began in the mud of the sum, drawn by a mining engineer who refused to watch men die without shelter.

There’s a poetic irony in that. Peter Norman Nissen, the man who built speed and efficiency into steel, died just before the world truly realized his genius. He was only 58 when pneumonia took him in 1930, never seeing his invention shelter another generation of soldiers through yet another world war.

And when war came again in 1939, Nissen Buildings Limited, waved all royalties, allowing Britain to produce the huts freely for the war effort. They didn’t make a fortune. Uh they made history across the Atlantic. The Americans industrialized the idea, refined the materials, and stamped their name on it. But even they never denied where it came from.

In official US Navy records from 1941, the Quanet is described plainly as an adaptation of the British Nissen Hut. It was imitation, yes, but also admiration. So, in the end, this isn’t a story of rivalry. It’s a story of two nations solving the same problem in their own way. Britain created the design that won time on the battlefield.

America scaled it into a symbol of global logistics. And together, they built something that outlived them both. A structure born from war, yet remembered for endurance, adaptability, and human ingenuity. Today, every arched steel shed, every prefab dome in disaster zones, and every emergency shelter on a distant shore still carries a trace of Niss’s curve.

A quiet reminder that the simplest ideas born in desperation can outlast empires.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.