A Texas Farmer Found 50 Fugitive German Female POWs in His Barn — What He Did Next Shocked the World. NU.

A Texas Farmer Found 50 Fugitive German Female POWs in His Barn — What He Did Next Shocked the World

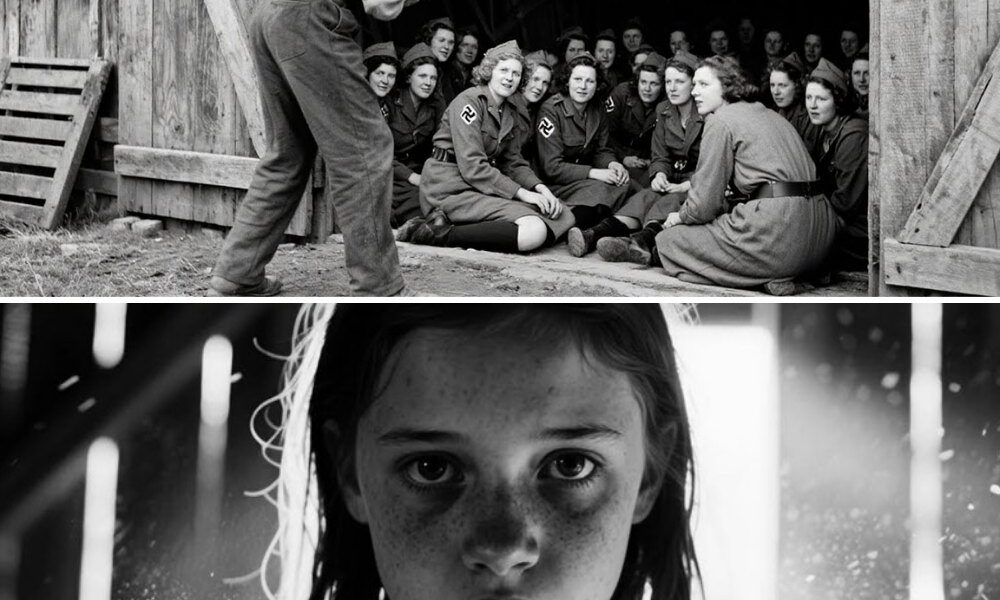

Fredericksburg, Texas. October 1944. Samuel Brown pushed open his barn doors at dawn, expecting the familiar smell of hay and livestock. Instead, he found eyes. 50 pairs of them staring back from the darkness. Women huddled in his hoft and stalls, dirt streaked faces showing exhaustion and terror in equal measure.

They wore faded prison uniforms. They spoke German in desperate whispers. They’d escaped from somewhere, fled through miles of Texas night, and chosen his barn as sanctuary. Samuel stood at the threshold, shotgun in hand, facing a decision that would define the rest of his life.

The sun had barely cleared the horizon when Samuel Brown began his morning rounds. October in the Texas Hill Country meant temperatures finally dropping from brutal to merely uncomfortable. Mornings crisp enough to require a jacket that would be shed by noon. He was 62 years old, a second generation German immigrant whose father had homesteaded this land in the 1880s, building a life from limestone and determination.

The farm sprawled across 300 acres wheat fields, a small cattle operation, chickens, the vegetable garden his late wife had planted, and he’d maintained from habit more than necessity. The barn stood 50 yards from the house, a structure his father had built from native stone and timber designed to last generations. It housed equipment, feed, and the two mules Samuel still used for work in the steeper terrain where tractors couldn’t navigate. He approached the barn carrying a bucket of feed mind on the day’s tasks. Fence repair in the north

pasture, harvesting the last of the fall vegetables, maybe riding into town for supplies, though gasoline rationing made every trip a calculation. The war had reached even into this quiet corner of Texas rationing. Scrap drives, young men disappearing into military service, never quite all returning.

The barn door stood slightly a jar. Samuel paused. He’d locked it last night. He was certain of that. Certain the way you’re certain about habits performed daily for decades. Winged couldn’t have opened it. The latch was secure, requiring deliberate lifting. He set down the feed bucket and retrieved his shotgun from where he depropped it against the fence post.

Coyotes had been troublesome lately, and vagrant workers occasionally sought shelter without permission. He approached quietly, boots crunching on gravel that sounded loud in the morning stillness. The barn door swung open with its familiar creek. Morning light streamed through, illuminating dust moes that danced in the air. The smell hit him first.

Not the expected aroma of hay and animal, but something else. Unwashed bodies. Fear. The metallic tang of exhaustion pushed past human limits. Then he saw them. Women filled his barn. They sat in the hoft, stood in empty stalls, huddled in corners behind equipment. 50 at least, maybe more.

They wore identical gray uniforms that hung loose on frames clearly undernourished. Their faces showed dirt and exhaustion, eyes wide, with a particular fear of people who’d reached the end of options. One woman stood at the front, older than the others, maybe 40, with iron gray hair pulled back severely. She stepped forward, hands raised in surrender or supplication. Bit, she said in German.

Please, we are hungry. We are dot dot dot g e flowhen dot dot dot escaped from camp. Please don’t shoot. Samuel’s shotgun stayed level. His mind raced through implications. P camp escapes, Germans, women, which was unusual most camps held men.

50 of them which suggested organization rather than opportunistic flight in his barn on his property making him complicit in whatever they’d done. “How long have you been here?” he asked in German. His father had insisted Samuel maintained the language despite being born in Texas, despite the anti-German sentiment of the First War. That insistence now felt prophetic. The woman’s eyes widened at hearing her language. Since last night late, we walked from Kev Swift.

Two days, maybe more. We followed the railroad, then the creek. We saw your barn from the ridge. We thought, “Dot dot dot dot dot dot dot.” Her voice broke. We are so hungry. The children especially. Children, she gestured to the back of the barn. In the darkest corner, Samuel now saw smaller forms girls, maybe 14 or 15, technically women, but barely.

They stared with eyes too old for their faces, hollowed by experiences Samuel couldn’t imagine. He lowered the shotgun slightly. Camp Swift is 60 mi east. You walked 60 mi. Some ran, some walked, some crawled the last miles. Three didn’t make it collapsed. couldn’t continue. We left them with water, hoped someone would find them.

She swayed slightly, exhaustion visible in every line of her body. We couldn’t go back. The camp something happened. Guards were there was violence, panic. The fence was damaged in the confusion. We ran. 52 of us initially, now 50. Samuel’s mind worked through scenarios.

Camp Swift was a major P facility holding thousands. A mass escape of 50 women suggested chaos, breakdown of security, something beyond routine flight. The authorities would be searching. Dogs, vehicles, aircraft, possibly finding them here would mean questions Samuel couldn’t easily answer. Consequences that could destroy what remained of his life. The right thing was obvious. Call the sheriff.

Report the escapes. Let proper authorities handle the situation. That was what the law required, what duty demanded. Samuel was a loyal American despite his German ancestry. He’d bought war bonds, sent his nephews to serve, accepted rationing without complaint.

But looking at these women exhausted, starving, terrified, he couldn’t see enemies. He saw his wife’s face in their desperation, remembered her final months when illness had reduced her to similar frailty. He saw his mother in the older woman’s stern dignity, the way she held herself upright despite obvious exhaustion. He saw humanity in its most vulnerable state. Asking for help he had the power to give or withhold.

“Wait here,” he said finally. “Don’t move. Don’t make noise. I need to think.” He walked back to the house, leaving the shotgun propped outside the barn. If they wanted to harm him, they’d had opportunity while he slept. The fact that they’d simply hidden suggested desperation rather than aggression. Inside the house, Samuel sat at his kitchen table, the same table where his father had made the decision to leave Germany, where Samuel had proposed to his wife, where they’d received news of nephews lost in this war. The table where decisions with weight got made. The sensible choice was

clear. Call authorities. Report the escapes. Protect himself from accusation of harboring fugitives. Let the system handle whatever had caused this mass flight. But Samuel thought about his father’s stories about leaving Germany because the old country had become something unrecognizable. about choosing Texas because America promised something different, not perfection, but the possibility of building life based on work and honesty rather than birthright and politics, about the importance of doing right, even when right was complicated. He thought about the young ones in the

barn. children really, despite what uniform or age might technically designate them. Hungry, terrified, having walked 60 miles through Texas wilderness on the desperate hope that someone would show mercy, Samuel stood and walked to his pantry. He began pulling out food.

By the time Samuel returned to the barn, arms loaded with bread, cheese, dried meat, and every apple from his storage celler, the women had organized themselves with military precision. The older woman who introduced herself as helped man Martha Keller, a communications officer captured in North Africa, had established order. The women sat in rows, quiet and disciplined despite obvious hunger and exhaustion.

I’m going to feed you, Samuel said in German. Then we need to talk about what happens next. He distributed food, watching 50 starving women maintain discipline as they ate. No fighting, no grabbing, careful rationing among themselves. The oldest made sure the youngest ate first. Those with injuries received extra portions.

The organization spoke of training, but also of something deeper communal care forged through shared hardship. Keller approached while the women ate. Hair Brown, she said, having noted his German surname on the mailbox. We don’t expect charity. If you feed us, we can work. We’re trained medical personnel, communications, logistics. Whatever you need done, we can do it. We just need time to figure out what to do next.

What happened at the camp? Samuel asked. Why did you run? Keller’s face darkened. There was an incident. Allegations of mistreatment. Some of the guards, not all, but some. They’d been using their authority inappropriately with female prisoners. When it came to light, there was panic, violence, chaos. In the confusion, part of the fence failed. We saw opportunity and took it.

We knew the consequences of staying outweighed the risks of flight. Samuel felt anger rising in his chest. Whatever America’s faults, whatever justified criticism existed, the systematic mistreatment of prisoners under protection violated everything he believed his country stood for. All 50 of you faced this? No. But we’re all part of the same unit.

captured together, held together. When the youngest ones were threatened, the rest of us chose solidarity. We protect our own. Keller met his eyes steadily. I understand you’re taking enormous risk helping us. You could turn us in. Protect yourself. We wouldn’t blame you. But if you give us a few days, just days, we can contact proper authorities through Red Cross channels.

Report what happened. Ensure testimony is documented before we return to military custody. That’s all we’re asking. Chance to tell truth without it being buried. Samuel looked around the barn. 50 women who’d walked 60 mi rather than accept mistreatment. Who’d maintain discipline and care for each other through what must have been a nightmarish journey.

Who were asking not for permanent refuge but simply for time to ensure justice before surrendering. You can stay, he heard himself say. 3 days I’ll provide food, shelter, water. You’ll stay out of sight. My nearest neighbor is 2 mi away, but hunters use these hills. After 3 days, we contact Red Cross together.

Arrange proper surrender with guarantees about investigation. Agreed. Keller’s eyes filled with tears. She refused to let fall. Thank you. Thank you. Well repay this kindness. Somehow you’ll repay it by staying hidden and staying quiet, Samuel said practically. And by helping with farm work if you’re able. I can’t run this place alone my wife passed 2 years ago.

My sons live in Houston. If you’re working, you’re less likely to be noticed if anyone does come around. Over the following hours, the barn transformed into organized camp. The women cleaned themselves using wellwater Samuel provided in buckets. They washed their uniforms.

Samuel provided clothesline rope and soap and wore his late wife sess clothes while the uniforms dried. The sight of German pose wearing his Greta’s dresses created a surreal dissonance Samuel couldn’t quite process. Keller organized work details. Those with medical training examined injuries from the journey, blistered feet, dehydration, a twisted ankle, various cuts and bruises.

Those with strength began farm work under Samuel’s direction. Within hours, his neglected fence line was repaired, his vegetable garden harvested, his equipment organized with Germanic efficiency. “You’re too good at this,” Samuel observed, watching them work. This isn’t survival desperation. This is trained competence.

A younger woman named Elsa, who spoke better English, smiled slightly. We’re German military personnel. Efficiency is what we do. Camp taught us American agricultural methods. We’ve been working farms around the camp for months. This is familiar labor. By evening, Samuel’s farm looked better than it had in 2 years.

The women had accomplished in hours what would have taken him weeks. They’d organized his barn, repaired structures he’d been putting off, even started repairs on his tractor that had been sitting broken since spring. Dinner was communal. Samuel cooked, or more accurately, supervised while German military cooks transformed his basic ingredients into a meal that fed 52 people.

They ate in the barn, sitting on hay bales, talking quietly in German about families, homes, the lives they’d left behind. Samuel sat with Keller and several of the older women. “Tell me about yourselves,” he said. “Not as soldiers or prisoners, as people.” The stories emerged slowly. Greta, not his wife.

A different Greta had been a school teacher in Munich, conscripted into communications work because she spoke French and English. Anna was a nurse from Hamburg who’d volunteered for military service thinking it was duty. Lisel had been studying medicine when the war interrupted, found herself assigned to field medical units.

Each had a story of ordinary life disrupted by war, of choices made with limited information, of finding themselves far from home in circumstances they’d never imagined. “Do you believe in what you fought for?” Samuel asked carefully. Keller answered, “Most of us believed in defending our country. Some believed in the regime’s promises.

But belief has been tested by reality. the things we’ve seen, the truth about what was being done in Germany’s name. It’s complicated. We’re Germans. That won’t change. But we’re not what the propaganda said we were. And Germany isn’t what the propaganda said it was. We’re learning that in captivity. Learning that enemies can be kind, that strength doesn’t require cruelty, that there are different ways to live than what we were taught.

Samuel thought about his father’s decision to leave Germany. The old man had seen something in his homeland that troubled him enough to cross an ocean. Now his son sat in a Texas barn feeding German prisoners, hearing them describe the same disillusionment that had driven his father to Texas 60 years prior. Tomorrow, Samuel said, we work on contacting the Red Cross.

We start documenting what happened at Camp Swift. We prepare for your eventual surrender. But we do it right with guarantees that your testimony will be heard. That investigation will happen. That you’re not just returned to silence. The women nodded. In their faces, Samuel saw relief mixed with lingering fear. They’d take an enormous risk fleeing.

They’d put their lives in the hands of a stranger who could betray them easily. But they’ chosen to trust human decency over system failure. And somehow, impossibly, they’d found what they needed. That night, Samuel sat on his porch, looking toward the barn where 50 German women slept in his hay. His father would have understood this choice. His wife certainly would have.

The law might not, but laws written by men sometimes failed to account for complicated human circumstances. He’d harbor them for 3 days, help them tell their story, then arrange proper surrender. It wasn’t legal, wasn’t safe, wasn’t sensible by any conventional measure, but it was right in a way that transcended those considerations.

And sometimes Samuel believed doing right mattered more than doing legal. Dawn of the first full day brought structure. Keller organized the women into shifts. Some worked Samuel’s farm, others rested. And recovered, a few began documenting their allegations in careful German that Elsa translated into English.

The barn became command center, infirmary, dormatory, and workspace simultaneously. Samuel rode into Freicksburg midm morning, ostensibly for supplies. In reality, he needed to gauge whether search efforts were visible. The town buzzed with news. A mass escape from Camp Swift. 50 women missing. Search parties deployed. But the search was concentrated east along direct routes between the camp and Mexico.

No one imagined the escapes would flee west, deeper into Texas toward the hill country rather than the border. At the general store, Samuel bought extra supplies, more food than one man needed, but not so much as to raise obvious suspicion. The storekeeper, Martha Hoffman, noticed anyway. That’s a lot of flour, Sam, she observed. Thinking about doing more baking.

Greta always said I should learn. Seems like time to try. Martha nodded sympathetically. Missing her more this time of year, I imagine. Fall was her favorite season. The comments stung with truth. Greta had loved autumn. In the cooling weather, harvest time, the way lightsed gold across the hills, she’d have known exactly what to do with 50 scared women in the barn. Probably would have invited them into the house.

Truth be told, back at the farm, work continued. The women had harvested his entire vegetable garden, preserving what could be preserved, storing what could be stored. They’d repaired every fence line, organized his tool shed with military precision, even started maintenance on his windmill, and had been squeaking for months. “You’re too efficient,” Samuel told Keller. “You’re making me look bad.

Neighbors will wonder how I suddenly got so much done. Would you prefer we work slower?” Keller asked with slight smile. “I’d prefer you stay hidden. But since you’re here, might as well let you fix things I’ve been putting off for 2 years. By afternoon, Samuel had set up a makeshift office in his house.

Keller and three others with legal or administrative training began preparing documentation. They wrote detailed accounts of incidents at Camp Swift names, dates, specific allegations. They prepared testimony for Red Cross investigation. They drafted requests for transfer to different facilities under proper supervision. Elsa served as translator, her English proving fluent. I studied literature at university, she explained.

Before the war, I was going to be a teacher. Now I’m translating prisoner complaints in a Texas farmhouse. Life is strange. What will you do after the war? Samuel asked. I don’t know. Germany will be destroyed. That’s obvious now. Maybe stay in America if possible. Maybe teach German to American students or teach English to German refugees.

Use language skills to build bridges instead of defend borders. She paused. Your German ancestry? Yes. Your father came from Germany? 1882. From va. He said Germany was becoming something he couldn’t support. So he left. Smart man. I wish Moore had his foresight.

Maybe if Moore had left, less had stayed silent, things would be different. Elsa returned to translating, but Samuel saw tears on her cheeks. The second day brought unexpected visitors. Samuel was working in the field with several women. They wore his late wife’s clothes and sun hats. Could pass for hired help at distance when a sheriff’s vehicle approached down his long driveway. Get to the barn,” Samuel hissed.

Now quietly, the women vanished with practiced speed. By the time Sheriff Tom Vber reached Samuel, the farmer was alone, repairing fence like he’d been doing it all morning. “Morning, Sam,” Vber called. “Got a minute? Sure thing, Tom? What brings you out? That escape from Swift.

50 German women been missing three days now. Search parties are covering the area. Haven’t come across anyone unusual, have you? Samuel’s heart pounded, but his face stayed calm. Can’t say I have. Been pretty quiet out here. What makes you think they’d come this way? Probably wouldn’t, but we’re checking everything within a 100 miles.

Mind if I look around? Samuel’s mind raced. The bar was full of evidence, too much for 50 women to hide completely, but refusing search would raise immediate suspicion. Sure, he said, though I don’t know what you expect to find. Been just me and the livestock for months now. They walked toward the barn.

Samuel’s mouth went dry. If Vber looked in the hoft, if he noticed the organization, if he found any of the women who couldn’t evacuate fast enough. Vber paused at the barn door. Place looks good, Sam. Better than last time I was out here. Been keeping busy. Idle hands and all that. Ver scanned the barn interior. Samuel held his breath.

The space looked normal equipment. Hey, feed. No obvious sign of 50 women living there. Keller had planned for this. He realized they’d known searches were possible, had organized with that threat in mind. Well, keep your eyes open, Vber said finally. These women are desperate, might be dangerous.

You see anything suspicious? Call immediately. Don’t try to handle it yourself. We’ll do, Tong. After Vber left, Samuel sagged against the barn wall. Keller emerged from behind a false wall in the tack room where they’d hidden. “That was close,” she said. “Too close. We’re running out of time. We need to contact Red Cross today.

” That afternoon, Samuel drove to Austin, a 2-hour trip that consumed precious gasoline rations. At the Red Cross office there was staffed by people who could initiate proper channels. He met with a representative named Dorothy Chun, explaining carefully, choosing words that conveyed urgency without exposing too much too fast. I have information about Camp Swift, he said.

About the women who escaped. They’re willing to surrender, but only with guarantees. Investigation into what caused the escape, transfer to different facility, protection from retaliation. Chun listened with professional calm. That’s quite serious allegation, Mr. Brown.

Do you have evidence, documentation, testimony, witnesses ready to provide sworn statements, but only with proper protections in place first? Where are these women now? Safe. That’s all I’ll say until I have your guarantee that this will be investigated properly. Chun made phone calls, consulted with supervisors. The process took hours, but finally she returned with an answer.

We can arrange supervised surrender. Military police will take custody, but Red Cross observers will be present. Investigation will be opened immediately. The women will be transferred to Camp Ko in Mississippi pending investigation results. But this needs to happen soon every day. They remain at large increases legal jeopardy for everyone involved.

Tomorrow, Samuel said, “At my farm, we’ll need assurance of safe transport, proper medical examination, and documentation of their condition at surrender.” Agreed. Be at your farm at 1,000 hours tomorrow. We’ll have appropriate personnel present. The drive back to Frederick’sburg felt longer than the drive out. Samuel’s hands shook on the wheel.

He just admitted to harboring fugitives, set in motion events. that could still result in his arrest, but he’d also potentially protected 50 women from returning to dangerous situation without oversight. At the farm, he gathered the women in the barn tomorrow morning, 1,000 hours. Red Cross and military police will arrive.

You’ll surrender with guarantees investigation, transfer, observers present throughout. It’s the best I could arrange. The women absorbed this with mixed reactions. Relief that the hiding was ending. Fear about what came next. Gratitude for time they’d been given. Keller stepped forward. Hairbr can never repay what you’ve done. Risking yourself, your home, your freedom for enemy prisoners you’d never met.

This isn’t how we were told Americans would treat us. How were you told? that Americans were soft, weak, concerned only with comfort and profit, that they’d never risk anything for principle. She smiled slightly. The propaganda was wrong about that, too. That final night, the women prepared to leave. They cleaned the barn meticulously, removing all trace of their presence.

They returned Samuel’s late wife’s clothing, washed and folded with care. They left his farm better than they’d founded fences repaired, equipment maintained, even a vegetable garden planted for spring that Samuel wouldn’t have to manage alone. A young woman named Sophia approached Samuel as he sat on his porch, watching the sunset over hills his father had chosen 60 years earlier.

“I wanted to thank you personally,” she said in halting English. “Not just for hiding us, but for seeing us, his people. Most guards at camp, they saw uniforms. You saw humans. My father taught me that. Samuel said that uniform or accent doesn’t change what’s underneath. We’re all just trying to survive, do right, find meaning in circumstances we don’t control.

Will you be in trouble for helping us? Maybe. Probably. But some troubles are worth having. My wife used to say, “You can’t die with your decency intact if you never risk it.” She’d have approved of this choice. That matters more than legal consequences. Morning arrived cold and clear. The women dressed in their prison uniforms, cleaned and repaired as best possible.

They stood in formation in Samuel’s yard, disciplined and dignified, despite exhaustion and fear about what came next. The vehicles arrived precisely at 1,000 hours. Military police in two trucks. Red Cross representatives in a sedan. A doctor and nurses in an ambulance. The convoy raised dust on Samuel’s long driveway announcing arrival with deliberate visibility.

Lieutenant Colonel James Harrison emerged from the lead vehicle. He was older, career military, with a face that showed he’d seen complications before. A Red Cross observer, Dorothy Chun, who’ coordinated this surrender, stood beside him. Mr. Brown, Harrison said, “I understand we have a situation.” “Yes, sir.

These women escaped Camp Swift 3 days ago. They’ve been here under my protection. They’re ready to surrender, but only with guarantees of investigation and safe transfer.” Harrison surveyed the 50 women standing at attention. His expression showed surprise at their organization and condition. They look well cared for. They worked my farm in exchange for shelter and food.

They’ve been respectful, disciplined, and honest about their situation. Chon stepped forward with documentation. We’ve received testimony alleging serious misconduct at Cam Swift. These women are willing to provide sworn statements and cooperate fully with investigation, provided they’re transferred to different facility pending resolution. Harrison nodded slowly. Camp Ko in Mississippi already arranged.

They’ll be transported today, examined by medical personnel. Statements taken by military investigators. Mr. Brown, you understand you could face charges for harboring fugitives? I do. I’m prepared to face whatever consequences are appropriate. Given that you arranged their surrender and potentially prevented further incident, I’m recommending leniency, but you’ll need to provide full statement about events.

Over the next hours, the surrender processed with bureaucratic efficiency. Each woman was examined by medical personnel, their injuries documented, health status recorded. Military investigators took preliminary statements. Red Cross observers ensured proper procedure throughout. Keller approached Samuel before boarding the transport truck. We’ll tell them everything about the conditions that caused the escape.

About how you helped us, about the kindness you showed when you had every reason to turn us away. Just tell the truth, Samuel said. That’s all that matters. Truth about what happened at Swift. Truth about what you experienced here. Let the facts speak. Will we see you again? I don’t know. Maybe after the war if you return to this area or if you need someone to testify about your character.

I’ll be here. She handed him a folded paper. We wrote this together. All 50 of us. Keep it. Remember that we’re grateful even if we never see you again. The trucks departed, carrying 50 women back into military custody, but different custody than they’d fled with observers present, guarantees in place, investigation pending. Not perfect, but better than the alternative.

Samuel stood in his yard, watching dust settle on his driveway. His farm was empty again, quiet again, just him and the livestock and the endless Texas sky. But something had changed. The land itself seemed different, blessed somehow by having provided sanctuary when sanctuary was needed. He unfolded the paper Keller had given him.

It was written in German, 50 signatures below careful script, to Samuel Brown, who showed us that enemy is a political designation, not a human category, who risked everything to give us chance at justice. who fed us when we were hungry, sheltered us when we were hunted, treated us with dignity when we’d been treated as less than human. You didn’t do this for reward or recognition.

You did it because you saw people who needed help and you had the power to help. This is what we’ll remember about America. Not the camps or the captivity, but the farmer who opened his barn and saw not prisoners, but humans deserving care. We’ll carry this lesson back to Germany. Share it with future generations. Teach our children that kindness transcends nationality.

Thank you for showing us that our propaganda was wrong. That Americans are capable of moral courage our regime only pretended to have. You’ll never know the full impact of your choice. But we’ll spend our lives trying to be worthy of it.

Samuel folded the letter carefully and placed it in his pocket next to the photograph of his wife he always carried. Greta would have approved. His father certainly would have. That mattered more than whatever legal consequences might follow. Sheriff Vber arrived that afternoon having heard about the surrender. Herb You harbored those escaped prisoners. Sam, I did. gave them food, shelter, three days to prepare testimony about mistreatment at their camp, then arranged proper surrender with guarantees of investigation.

Vber was quiet for a long moment. That was either the bravest or stupidest thing you’ve ever done. Maybe both, but it was right. Authorities are deciding whether to press charges. Given that you arranged the surrender and potentially prevented further incident, I imagine they’ll choose leniency. But Samu took enormous risk. Risk worth taking.

My father left Germany because people weren’t willing to risk standing up for right. I wasn’t going to make his mistake by staying silent when I could act. Vber nodded slowly. For what it’s worth, I’d have done the same. wouldn’t tell most folks that, but between you and me, you did the right thing. The investigation that followed made national news. Camp Swift was temporarily closed pending inquiry.

Several guards faced courts marshall. Camp procedures were overhauled across the P system. The 50 women provided testimony that corroborated and expanded initial allegations, creating documentation that couldn’t be ignored or buried. Samuel gave his own testimony to investigators, explaining his decisions in straightforward language that acknowledged legal violations while asserting moral justifications.

The investigators listened with expressions that suggested they weren’t entirely unsympathetic to his position. Mr. Brown, the lead investigator, said, you violated multiple regulations regarding fugitive prisoners. You harbored enemy combatants. You failed to report escaped post to proper authorities. Under strict interpretation of law, these are serious offenses.

I understand. However, your actions potentially prevented further harm to vulnerable prisoners. You arranged voluntary surrender. You provided evidence crucial to investigation. Given these mitigating factors, we’re recommending no criminal charges. You’ll be placed under temporary observation, required to report regularly to local authorities for 6 months, but absent further incident, this matter will be closed.

Relief washed over Samuel, though he tried not to show it. Thank you. Don’t thank us. Thank the 50 women who testified on your behalf. They described you as exemplifying American values of justice and mercy. Their testimony was influential in our recommendation. The Red Cross wrote formal commendation. Fredericksburg’s German-American community, initially nervous about Samuel’s actions, gradually embraced him as someone who’d honored their shared heritage by refusing to tolerate injustice.

Even some who dequested his choice acknowledged that standing up for right had required courage they were unsure they possessed. Letters began arriving from the women at Camp Komo. They described better conditions, respectful treatment, proper procedures. They expressed continued gratitude for Samuel’s intervention.

Several mentioned plans to remain in America after the war to build lives that honored the kindness they’d received. One letter from Keller arrived in December. Hair Brown, I write to inform you that investigation concluded in our favor. Guards responsible for misconduct have been removed from P duty. Camp procedures have been reformed. We’re being treated with dignity and respect.

None of this would have happened without your courage to harbor us, to give us time to organize testimony, to arrange surrender with guarantees we’d be heard. You didn’t just save 50 lives. You potentially improved conditions for thousands of prisoners across the system. That’s legacy worth celebrating. When the war ends, several of us plan to return to Texas.

We’d like to visit your farm. Thank you properly. Help you with work as small repayment for enormous debt. Until then, know that you’re remembered in our prayers and thoughts. You showed us America at its best. We’ll spend our lives trying to show Germany at its best in return. Samuel kept the letter with the one signed by all 50 women.

They represented something he struggled to articulate proof that moral courage could matter, that individual actions could ripple outward in unexpected ways, that choosing kindness over expedience could create change beyond immediate circumstances. His nephews, when they returned from the war, were initially shocked to learn what their uncle had done. But after hearing the full story, after understanding the context and considerations, they expressed pride.

You showed those women what America means. One said, “Not the system or the policies, but the idea that we’re people who help other people when we can, regardless of uniform or nationality.” Fredericksburg, Texas, 1955. Samuel Brown was 73 years old, still farming the land his father had homesteaded.

The barn where 50 women had hidden now stood as reminder of choices that defined character. A car pulled up his driveway uncommon enough to warrant investigation. Samuel walked from his garden to greet the visitors. Four women emerged, middle-aged now, wearing civilian clothes and speaking English with German accents. Hair brown.

One said Martha Keller. We met in your barn long time ago. Samuel smiled, recognizing her despite years. Fra Keller, welcome back. We came to thank you properly and to help with farm work, if you’ll allow us. Several of us stayed in America, married, built lives here. We wanted you to know we never forgot. They spent the day working his land, the same land they’d worked a decade earlier as fugitives.

But now as free women, American citizens, living proof that enemies could become friends through simple acts of human decency. At sunset, sitting on his porch with these women who’d once hidden in his barn, Samuel reflected on his father’s choice to leave.

Germany his own choice to harbor fugitives the cascade of decisions that had led to this moment. “Did you ever regret it?” Keller asked. “Helping us, risking so much? Never, Samuel said honestly. My wife used to say, you can’t die with your character intact if you never risk it. I risked mine for 3 days in October 1944. Best decision I ever made. The women nodded. They understood.

They’d risked their lives fleeing Camp Swift. They’d trusted a stranger with their safety. They’d chosen to believe in human goodness despite years of evidence suggesting cynicism was safer. to choices that define us,” Keller said, raising her glass of lemonade. “To moral courage,” Samuel replied. They drank.

The Texas sunset painted the hills in colors that transcended language or nationality. Beauty that existed regardless of human conflict, that promised continuity beyond individual lives. Samuel’s barn stood against the darkening sky, sheltering livestock and hay and memory. 50 women had hidden there once, desperate and afraid.

One farmer had chosen kindness over expedience, shelter over security, right over easy. The story spread over years, told and retold, embellished sometimes, but rooted in truth. It became legend in Fredericksburg, reminder that moral courage could bloom in unlikely places. That individual choices mattered even in contexts of war and ideology.

Most importantly, it showed that enemy was political designation, not human category. That feeding the hungry, sheltering the vulnerable, choosing kindness, these were obligations that transcended nationality or circumstance. Samuel Brown had opened his barn to 50 fugitive Germans. In doing so, he’d opened door to transformation that rippled across decades improving P conditions, saving lives, demonstrating that American ideals could manifest through individual choices rather than just government policy. His father had

left Germany seeking America’s promise. Samuel had honored that promise by treating enemies with dignity they’d been denied. The circle was complete immigrant son proving immigrants faith justified showing next generation what courage looked like when character was tested.

The women departed at evening’s end promising to return to maintain connection forged in barn during three October days. Samuel watched them go and walked to his barn touching the stone his father had laid 70 years earlier. Some structures sheltered animals, others sheltered humans. A few in rare moments sheltered both, and in doing so demonstrated that civilization has measure, was in wealth or power, but willingness to extend care regardless of who was asking.

Samuel Brown had measured well. His barn had, too.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.