Heinrich Himmler is remembered as one of the central architects of Nazi terror: the Reichsführer-SS who presided over a vast empire of police power, concentration camps, and racial persecution. The name “Himmler” is so closely tied to the SS and the Holocaust that it can feel as if Heinrich emerged fully formed, a singular villain detached from ordinary life. He did not. He came from a respectable Catholic household in Bavaria, and he grew up with two brothers, Gebhard Ludwig Himmler and Ernst Hermann Himmler, raised under the same roof, the same rules, and the same social ambitions.

This is not a story of one monster surrounded by innocence. It is a story about how extremism becomes normal inside families and institutions. It is also a story about what happened after 1945, when one brother died in the ruins of Berlin, one swallowed cyanide in British custody, and one sat before Allied investigators insisting his brother had been personally kind.

A strict household, a familiar script

The Himmler boys were born into order. Their father, Joseph Gebhard Himmler, was a teacher of Greek and Latin who took pride in status and good connections. In family lore, he had once tutored Bavarian royals, a detail he liked to mention. Their mother, Anna Maria, ran the household with strict routine: Mass on Sundays, prayers before meals, rules for everything, and an expectation that boys should be disciplined and ambitious.

In later retellings, these were “good” values—faith, work, obedience, clean uniforms, good grades. In hindsight, the same training could be repurposed as habit: do what authorities demand, value hierarchy, and treat conformity as moral duty. Nothing in the home guaranteed that the sons would become Nazis, but the home did teach a comfort with systems that reward obedience and punish dissent.

The brothers attended good schools, wore uniforms, and learned early that approval came from performance. Their father expected achievement and reminded them of it, not gently, but as a constant pressure. In a household like that, failing was not a private disappointment; it was a moral weakness. The boys learned to present themselves as “upright” and to treat reputation as something you build and defend.

That focus on reputation helps explain a later family reflex: the urge to protect the Himmler name after the war by narrowing guilt to a single person. A family trained to equate status with worth will often cling to any story that keeps its status intact, even when the facts are corrosive.

Gebhard was born in 1898, the first son. Heinrich followed in 1900. Ernst arrived in 1905, five years behind, watching the older two define what “success” looked like. In family photographs from the early 1900s, the scene is conventional: parents standing behind children, faces composed, a careful performance of middle-class stability. These images later became part of the family’s psychological defense, proof, in their own minds, that they had been ordinary and therefore could not have been deeply implicated.

War and envy

World War I created the first major fracture in the brothers’ identities. Gebhard was old enough to serve. He trained, joined the Bavarian Army, and reached the Western Front late in the conflict. He fought in a world of mud, artillery, gas, and exhaustion, where survival could feel accidental. He returned home carrying the aura of a veteran, the kind of son their father admired: tested, decorated, and able to speak the language of sacrifice.

Heinrich trained as an officer cadet but never reached combat before the armistice. In a culture that prized medals and service, the “missed war” could feel like personal humiliation. Biographers note that Heinrich carried this failure as a grievance. His elder brother had proof of courage; he did not. That gap mattered because it shaped a craving to belong to a cause that promised status, uniforms, and a path to historical significance.

For Heinrich, politics offered what the war had denied him: a stage where loyalty could be measured in symbols rather than battlefield deeds. Party work, marches, and paramilitary discipline provided a substitute for military glory. It also allowed him to define enemies and imagine himself as a defender of “order,” a role that can feel heroic when a society is frightened and unstable.

Ernst was a child during the war, old enough to absorb defeat but too young to have any control over it. He grew up in a Germany that struggled to explain the collapse of an empire and the hardships that followed. In families like the Himmlers, the postwar years did not produce humility; they produced a search for restoration—an appetite for movements that promised order, discipline, and national rebirth.

Paramilitary politics and the road to Hitler

After 1918, Bavaria was a laboratory of instability. Street violence, coups, and political fear became part of daily life. Paramilitary groups formed and offered young men a new script: if the state is weak, a disciplined brotherhood can restore order. Both Gebhard and Heinrich passed through this world. They joined organizations that promised belonging and direction, and they learned to treat political violence as legitimate.

In 1919 the brothers moved from the citizens’ militia into the Freikorps orbit. Gebhard joined a unit under Franz Ritter von Epp, formed to crush leftist uprisings in the chaos of postwar Munich. The shift mattered: it turned politics into a battlefield and taught men that violence could be framed as civic necessity.

In 1923, Adolf Hitler attempted to seize power in Munich in what became known as the Beer Hall Putsch. Heinrich, already active in the Nazi Party’s paramilitary circles, was involved in the coup attempt. The putsch failed. Police fired on marchers. Hitler was arrested. But for those who had marched, failure became a credential. Participation marked them as early believers, and that early loyalty would later be rewarded.

Gebhard’s relationship to the early Nazi movement was shaped less by street theatrics and more by career. He studied mechanical engineering and worked in banking and technical education. He was the kind of man who understood institutions and credentials. Those skills would become valuable when the Nazis transformed the state into a machine of classification, advancement, and exclusion.

Ernst’s path was technical, but not apolitical. He completed university studies in electrical engineering in 1928. In 1931 he joined the Nazi Party, before Hitler came to power. Joining early was riskier than joining later; it suggests belief rather than opportunism. Yet later family narratives often tried to minimize Ernst’s politics by framing him as “just” a technician.

Three careers inside one regime

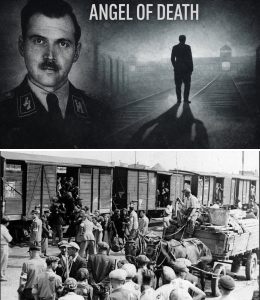

When Hitler became chancellor in 1933, the Himmler brothers’ choices solidified. Heinrich rose rapidly through the SS. He transformed the SS from a small elite unit into a vast organization that absorbed police powers, intelligence functions, and camp administration. He became one of the most powerful figures in the Third Reich and a central organizer of the Holocaust. His rise mattered inside the family because it turned the surname into leverage. In Nazi Germany, access often moved through personal networks. A brother of a powerful man did not need to give explicit orders to benefit; doors opened, positions became easier to secure, and criticism became risky. The Himmler family could tell itself that it was simply “successful,” while the state around it was turning success into violence.

His authority did not rely solely on charisma. It relied on bureaucracy: forms, files, classifications, and chains of command that made mass murder feel like “procedure.”

Gebhard’s career advanced once the Nazis took power. He became headmaster of a vocational school in Munich in 1933 and later headmaster of the Oskar von Miller Polytechnic, a higher institution specializing in technology. On paper, this looks like harmless education work. In practice, Nazi education was not neutral. It was a gatekeeping system. Technical training determined who could become an engineer, who could enter management, and who would be blocked, expelled, or redirected as “politically” or “racially” undesirable.

Gebhard joined the Nazi Party in 1933. But there was an image problem. Joining at the moment Hitler took power made a person look opportunistic in the eyes of “old fighters” who wanted to be seen as believers from the start. Gebhard solved this by arranging to have his wife’s lower party membership number transferred to him, making it appear he had joined earlier. The deception is small, but the motive is revealing: in a dictatorship, appearance and loyalty are professional assets.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, Gebhard moved into higher administrative roles linked to technical schooling and the Reich Ministry of Education. There, questions about “merit” could never be separated from ideology. The regime needed engineers and technicians for armaments and infrastructure, but it also demanded racial conformity and political reliability. Gatekeepers like Gebhard did not have to shoot anyone to cause harm; they simply had to decide who belonged and who did not.

His SS rank further complicates the postwar story that he was “only” an educator. By 1944 he held the rank of SS-Standartenführer, and his wartime postings connected him to Waffen-SS school oversight. Titles like these were not decorative. In Nazi Germany, rank signaled inclusion within an elite system that claimed ideological purity and demanded service to the regime’s goals.

Ernst’s contribution was less visible but no less consequential. With Heinrich’s help, he obtained a position in Berlin’s broadcasting world and rose into leadership roles inside the Reich broadcasting system. Nazi power depended on repetition and spectacle: rallies, speeches, orchestrated public rituals, and “news” that framed the regime as both modern and inevitable. Engineers like Ernst made propaganda technically possible at scale. In a dictatorship, the microphone is not neutral. It is a weapon of persuasion.

The regime understood broadcasting as strategic power. The Nuremberg rallies were designed as theater, with choreography, lighting, and mass participation. Broadcasting extended that theater beyond the rally grounds into homes and workplaces. The 1936 Berlin Olympics, heavily used as a propaganda showcase, likewise relied on modern communications to project an image of efficiency and normalcy.

Engineers were essential to that performance. A rally without sound is just a crowd; a rally with a broadcast becomes a national ritual. Technical managers controlled what the public heard and how reliably they heard it. In a system that demanded emotional unity, signal clarity was political power. Ernst’s career therefore sits in the same moral space as more visible propaganda figures: he enabled the message to travel.

Ernst’s work belonged to that infrastructure, and later accounts describe him as reaching SS rank and supplying information within elite networks.

The letter that breaks the family myth

For decades after the war, the family story was convenient. Heinrich was the aberration, the monstrous exception. Gebhard was “just” a teacher and administrator. Ernst was “just” an engineer. That myth depended on two tactics. First, it separated technical and administrative work from moral responsibility. Second, it treated family loyalty as evidence of innocence.

A later generation found the cracks. Katrin Himmler, Ernst’s granddaughter and Heinrich’s great-niece, began researching family records as an adult. She discovered documents showing that both brothers had joined Nazi organizations voluntarily and benefited from Heinrich’s rise. She also found evidence that her grandfather’s actions were not passive. In interviews and in her book about the family, she described her most disturbing discovery: a letter in which Ernst, writing to Heinrich, dismissed the usefulness of a Jewish engineer who sought protection, knowing the likely consequences in the regime’s classification system.

Her research emphasized something uncomfortable: the Himmlers were not monsters in appearance or manners. They were educated, ambitious, and socially conventional. In her telling, that normality is precisely what makes the story important. Mass violence is not carried out only by cartoon villains. It is built by networks of ordinary professionals who decide that career, loyalty, and ideology matter more than the lives of strangers.

Katrin’s work also illustrates how silence functions. Families do not always invent whole histories. They omit. They smooth edges. They remember promotions, not the policies behind them. They remember kindness to relatives, not harm to strangers. The omissions are tidy, and they allow a family to live with itself.

Collapse in Berlin, cyanide in custody

By 1943 and 1944, Allied bombing raids made Berlin dangerous even for those inside the regime. The brothers experienced the war’s collapse from inside the state they served. Yet the Nazi system continued to demand loyalty as reality broke down.

In the spring of 1945, Berlin became a battlefield. Soviet forces closed in, and the regime mobilized the Volkssturm, a last-ditch militia that conscripted men outside regular military service. Ernst, a radio engineer rather than a frontline soldier, was called up and killed in action on 2 May 1945 during the Battle of Berlin. His death is often described as futile: defending a regime that was already finished, in fighting that continued even after Hitler’s suicide.

Heinrich’s end came weeks later. He attempted to disguise himself after Germany’s defeat, but British forces captured him. During processing, he bit down on a cyanide capsule hidden in his mouth and died on 23 May 1945. The most feared SS leader avoided a courtroom, leaving historians and prosecutors to assemble accountability through documents rather than testimony.

Gebhard lived, and living created a second career: postwar survival. He fled Berlin, was arrested, and faced denazification. He was assessed as a “follower,” a category that allowed many former Nazis to avoid the harshest penalties. He lost pension rights but appealed successfully and had them restored in 1959. Later he worked in Munich as a study adviser in an office supporting Afghan students, arranging internships and helping them navigate German universities. The irony is difficult to miss: a man who had advanced inside a racialized state later helped young foreigners enter German education.

Denazification and the comfort of categories

Denazification was designed to purge Nazi influence and restore civic life, but it had built-in limits. It relied on categories—major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, followers, and exonerated persons—that could compress complex responsibility into a label. In practice, the “follower” category often became a path back into normalcy.

Many people filled out long questionnaires describing jobs, party memberships, and wartime roles. Panels weighed evidence and often relied on recommendations from local figures who had their own incentives to rehabilitate neighbors and colleagues. The process produced a kind of moral inflation: as millions claimed they were merely “following,” the category expanded to fit them. For some, it meant temporary penalties. For others, it meant the difference between public disgrace and a quiet return to professional life.

Many people who had benefited from the regime, or helped administer it, were reclassified as minor participants and returned to professional life.

Gebhard’s postwar statements also reveal how private loyalty can soften public truth. When questioned about Heinrich, he defended him personally, insisting he could not see Heinrich as responsible for the SS’s crimes. The statement is chilling not because it is unusual, but because it is familiar. It is the language of moral compartmentalization: he was kind to me, therefore he cannot be guilty.

Why the brothers matter

To talk about Himmler’s brothers is not to distract from Heinrich’s crimes. It is to clarify how those crimes were embedded in social and professional systems. Heinrich built the SS into the regime’s most feared instrument and helped coordinate genocide. Gebhard advanced inside technical education and the ministry world, gained SS rank, and helped administer a state where opportunity and exclusion were guided by ideology. Ernst helped maintain the broadcast machinery of propaganda, held SS rank, and—according to later research—used family access in ways that harmed others.

None of these roles required theatrical sadism. The regime did not need every participant to be a fanatic with a gun. It needed competent people who would do their job inside a state that defined “job” as the management of human categories. It needed people willing to accept that a memo could become a sentence.

The most frightening lesson is not that Heinrich Himmler had brothers. It is that their lives show how easily respectability can coexist with brutality, and how long a family and a society can insist on innocence by shrinking responsibility into smaller, more comfortable stories.

The collapse of the Third Reich did not automatically produce moral clarity. One brother died in Berlin’s ruins. One died by his own poison. One lived on, appealed, worked, and never publicly repented. Decades later, a descendant opened the files and refused to keep the family legend intact.

Reading this history is uncomfortable because it does not let us blame everything on a single madman. It asks us to watch the quiet choices: the promotion accepted, the joke repeated, the letter mailed, the form stamped, the silence kept until the damage becomes ordinary again.

Katrin Himmler’s public work showed how painful that refusal can be. She appeared in a documentary about descendants of Nazi perpetrators, describing the strain of carrying a notorious name while trying to live an ordinary life. She later co-edited and published a collection of Heinrich Himmler’s private letters with a historian, choosing exposure over comfort. Her point was not to claim virtue by confession, but to insist that the past cannot be managed like a family secret.

In that sense, the last act of the Himmler story is not committed by any of the three brothers. It is committed by someone born long after the war, who decided that truth matters more than inheritance.

That is where this story ends, not with a single dramatic scene but with a question that remains urgent in every era. When a system asks ordinary people to do extraordinary harm, how many will say no, and how many will quietly find a way to make it work?