One Leather Notebook Changed Everything: The Canadian Nurse Who Saved 412 German Wounded—Then Got Captured._NU

One Leather Notebook Changed Everything: The Canadian Nurse Who Saved 412 German Wounded—Then Got Captured.

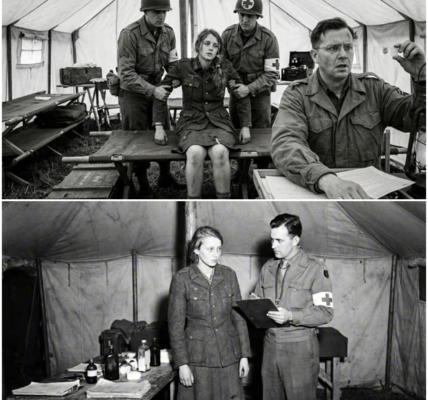

ORTONA, ITALY — December 1943. In a dim canvas tent four miles behind the front, the war sounded like it always did: men groaning, boots scraping on packed earth, metal instruments clinking against trays, and distant artillery rolling like weather. The surprise was not the noise. The surprise was the calm voice cutting through it.

“Hold still. Breathe. You’re safe here.”

Nursing Sister Grace McFersonson stood in the center of a Canadian casualty clearing station with her sleeves rolled above her elbows and a Red Cross armband on her left arm. Her apron, once white, had been stained brown and rust-red by days of continuous work. She tied off a fresh bandage on a Canadian corporal’s arm as a German patrol stepped through the tent flap and paused, struck by the smell of antiseptic layered over sweat, blood, and the sweet rot of infection.

Hauptmann Wilhelm Richter, a thirty-six-year-old officer from Hamburg, had walked through captured buildings across the war’s map — farmhouses in France, battered command posts in North Africa, schoolrooms turned into offices. He expected fear when his men crossed a threshold. Here he found routine. He found order. He found a woman who did not look away.

Richter’s patrol had seized the sector only hours earlier during a counterattack in the Battle of Ortona, the brutal week Canadians would later call “Little Stalingrad.” Street by street, room by room, the fighting left rubble where homes once stood. Medical units were already overwhelmed. Stations designed for 150 beds held two or three times that number. Men lay on stretchers between cots, boots still on, faces gray with shock. The line between front and rear moved like a living thing, and on 20 December it moved again — swallowing the hospital tents.

War correspondents later described Ortona as a town fought over in fragments. Progress was measured in rooms, not streets. Infantry used demolition charges to “mouse-hole” through walls rather than step through doors covered by machine guns. The rubble did more than slow soldiers; it slowed stretchers. Medical orderlies carried men over broken stone while shells still fell, and ambulances queued in muddy lanes because there was no other path.

A casualty clearing station was meant to be a bridge between the battlefield and the larger hospitals farther south. It was where the wounded were sorted, stabilized, and either saved or lost. Triage happened fast: a quick look at a wound, a pulse felt through a glove, a tag tied to a wrist. Some men were rushed to surgery. Some were given morphine and a blanket and placed where a nurse could hold their hand. The staff worked in shifts that existed on paper and disappeared in practice.

At Grace’s station, tents were packed so tightly that nurses walked sideways between cots. The ground turned to mud mixed with blood. Boots stuck. Lanterns threw shaky light over faces that looked too young to be that tired. Supplies ran thin. Bandages were washed and reused. Penicillin was guarded like gold and rationed to cases that had a chance if infection could be stopped in time. Every choice carried a consequence that might be read later as mercy or mistake.

On 20 December, when German infantry moved through the olive groves toward the hospital compound, Grace had minutes, not hours. Evacuation was the standard answer, but standard answers fail when a man cannot be moved without dying on the stretcher. The doctors had men open on operating tables and others in shock, shivering under blankets. Some German prisoners lay among them, already sedated, already stitched. Grace made the simplest decision she could: she stayed with the patients she had.

Inside the main ward, Richter saw rows of cots. Canadian khaki. British badges. And then, to his confusion, German field-gray — not penned into a corner, not separated behind a rope, but mixed among the wounded from the other side. A German private lay beside a Canadian corporal. A German lance corporal slept next to a British sergeant. Fifteen German soldiers, then more, splinted and stitched with the same care given to everyone else.

On a wooden table near the nurse’s work area, metal identification tags lay scattered in dull lamplight. Richter picked one up. It was German. Another. German. Another. Dozens. Dog tags, the small official proof of a life, collected and logged like chart numbers.

Grace finished her task, wiped her hands on a cloth that would never be clean again, and faced the officer. She was younger than he expected, perhaps twenty-eight or thirty, thin with exhaustion, dark circles carved under steady eyes. She spoke slowly, in English, as if the language itself were a tool.

“I am Nursing Sister Grace McFersonson,” she said. “This is a medical facility protected under the Geneva Convention. These men are under my care.”

Richter watched her without blinking. “You have treated our men?” he asked, the German accent heavy on each word.

“I have treated wounded men,” Grace replied. “All wounded men who came through these tents.”

Her answer was not defiance. It was a statement of practice, spoken by someone who had been making the same choice every hour for weeks.

To understand why, you have to look back beyond Ortona’s ruined streets to a different kind of quiet: Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1915. Grace was born in the middle of the First World War to a father who worked as a pharmacist. She grew up watching him fill prescriptions and advise people who could barely afford to be sick — factory workers with influenza, mothers worried over feverish children, veterans who never fully healed. Her father helped whoever came to the counter. Payment mattered less than need. The lesson sat deep: when someone needs help, you help.

By 1938 Grace completed nursing training at Winnipeg General Hospital. She was twenty-three and working in Toronto when war returned in September 1939. Within months, the Canadian Army Medical Corps called for nurses willing to serve overseas. Grace volunteered early in 1940, joining thousands of Canadian women who would become Nursing Sisters in uniform. They trained in England for months, and it was not gentle. They learned battlefield wounds civilian hospitals rarely saw: shrapnel tears, crush injuries, burns, and infections that turned quickly fatal when supply lines broke. They learned emergency surgery, strict hygiene in impossible conditions, and how to keep a steady voice when men screamed.

In 1943, Grace was sent to Italy as the Allied invasion climbed from Sicily to the mainland and pushed north through mountains, rivers, and mud. She was assigned to a Canadian field dressing station attached to the 1st Canadian Division, then promoted to Nursing Sister in charge at a casualty clearing station near Ortona. The CCS sat close enough to the front that nurses could hear artillery and sometimes feel shells land nearby. It was the first major medical stop after the battlefield: if a man could be saved there, he could be shipped to larger hospitals farther from the guns. If he could not, he would be buried near the station before his name had time to feel real.

The rules about prisoners were clear on paper. Allied wounded would receive full treatment. Enemy wounded would be segregated and given only basic care until transfer to prisoner hospitals. In late 1943, the paper rules collapsed under the weight of reality. There were too many casualties, too few beds, and too few hands. Prisoner hospitals overflowed. Captured Germans began arriving at Canadian stations because there was nowhere else to put them.

At first, there were only a few dozen. Grace did not receive a speech, an order, or permission. She received bodies. Men burned, bleeding, shaking, whispering for water, crying for their mothers. In that moment the uniform became secondary to the wound. Grace made the choice that would later define her: she treated them.

She also wrote everything down.

Grace kept a leather notebook beside her instruments. Name, rank, unit, wound, treatment, outcome. The habit served two purposes. It created order in chaos, and it created a record no one could erase with opinion. By the end of November 1943, she had treated thirty-eight German wounded. By mid-December, 147. On 20 December, the morning the counterattack shifted the line over her tents, the number in her book reached 412.

Richter asked, quietly now, “How many?”

Grace walked to her desk, lifted the leather notebook, and brought it to him as if presenting a chart to a doctor. She opened it. Page after page of German names, written in neat hand, dates and treatments aligned like columns. The tally was not rumor; it was ink.

“Four hundred and twelve,” she said. “Between November and today.”

The tent held its breath. The only sounds were moans and the distant guns still pounding the town.

Richter read several pages. He recognized unit numbers from the sector. He recognized the pattern of real casualties, not invented heroics. He looked up at the nurse whose hands had been saving people his side called enemies.

“You are under German protection now,” he said at last. “You will continue your work. You will also treat our wounded who are brought here. Do you understand?”

Grace met his gaze. “I was already treating your wounded,” she answered.

Seven words, plain as bandages, and something in the tent shifted. Richter had come to capture an enemy medical station. Instead he walked into a place where the war’s logic had been bent by a nurse’s ethics.

For the next eleven days the casualty clearing station remained under German control. In that span, Grace was both prisoner and indispensable professional. German guards ringed the hospital compound, but their job was to protect the facility, not to lock her away. The Germans needed every medical station they could keep running; casualties were high on both sides, and a functioning CCS was rare. Grace and her nurses continued surgeries, transfusions, amputations, and endless dressing changes. They worked with the same urgency they had before the occupation, because urgency was not political; it was medical.

During the occupation, sixty-three new German casualties arrived at the station from the fighting around Ortona. Grace treated every one. She also continued caring for Canadian and British wounded already in her tents. The Germans did not segregate them. The cots remained mixed. The arrangement was born of necessity and held together by one constant: Grace’s refusal to change her standards depending on the uniform at the end of the bed.

Richter visited daily. Sometimes he brought German medical officers who consulted Grace on difficult cases. They asked her opinion about treatments and supplies. In the tent, rank meant less than competence. Grace was addressed not as a captured enemy, but as a colleague who happened to speak English.

On the fourth day, a German army doctor arrived from headquarters: Dr. Ernst Müller. His task was to assess the situation and recommend what to do with the Canadian medical staff. Should they be sent to a prisoner-of-war camp? Should they remain? Müller spent hours examining patients, reading Grace’s records, and watching procedures. He observed the use of penicillin — still new and precious — to prevent infection in wounds that would otherwise turn fatal. When he finished, he wrote a report recommending that Grace and her staff be allowed to continue working under German supervision, not as a favor, but as a practical necessity and an acknowledgment of uncommon professional conduct.

The recommendation was approved.

Among the German wounded who passed through Grace’s hands were men whose names would travel beyond the battlefield. Klaus Becker, twenty-one, arrived with severe burns after a shell ignited his uniform. Grace cleaned dead tissue, applied sulfonamide powder, changed dressings every few hours, and fought infection with the tools she had. Becker survived.

Friedrich Steiner arrived with a shattered shin from a mine blast. Many doctors would have amputated immediately. Grace spent hours cleaning the wound, removing shrapnel fragments, setting bone with pins, and pushing antibiotics on a strict schedule. Steiner kept his leg. He would limp for life, but he would walk.

Grace documented each case with the same neat handwriting, as if order itself were a form of mercy.

Word spread through German units that a Canadian nurse was treating their wounded with professional care. Some soldiers wrote letters home. One letter, later recovered, described her exhaustion and her insistence on changing bandages even when she could barely stand. The letters did not describe kindness as softness. They described it as labor.

On 31 December, Allied forces launched a counterattack and pushed the Germans back. The sector around the casualty clearing station was retaken. Grace and her staff were liberated. Canadian officers entering the compound expected devastation and disorder. Instead they found a hospital still functioning. Patients lay where they had been, receiving care. Records were intact. The mixed cots were still mixed, and the nurse in charge was still working.

Grace’s story traveled upward quickly. Newspapers at home loved the headline: a Canadian nurse had saved hundreds of German lives. A nomination for the Royal Red Cross followed, and for civilians the story fit a comforting frame — mercy triumphing in war. Inside military offices, the reaction was more complicated. Some officers argued she violated regulations by giving advanced treatment to enemy prisoners who might recover and return to the front. They asked a harsh question that sounded logical in a briefing room: had she saved a man who would later kill an Allied soldier?

The controversy reached Brigadier Frederick Stearns, the senior Canadian medical officer in Italy. After reading reports and testimony, he wrote a defense that cut through the debate with a clinician’s clarity. Any nurse who would allow a man to die without treatment, regardless of nationality, was not worthy of being called a nurse, he wrote. Critics, he added, had never worked in a casualty clearing station where men died by the dozens while staff fought shock, blood loss, and infection with limited hours and thinner supplies. In that environment, refusing care was not strategy; it was surrender of the profession’s core purpose.

A German message later arrived through neutral Switzerland acknowledging Grace’s humanity and skill. Neither side wanted a public ceremony with the enemy, but the acknowledgment was recorded in official files — a quiet note that even in war there were actions that did not fit propaganda.

Grace returned to work. Ortona’s fighting moved on. Over the course of the Italian Campaign, her stations treated thousands of Allied casualties and, eventually, more than 1,600 German wounded. Her facility’s survival rate for German prisoners was markedly higher than typical, in part because she insisted on equal standards: the same antibiotics, the same urgency, the same careful dressing changes, the same willingness to sit with a frightened man until his breathing eased.

Years later, those numbers would be quoted as evidence. Grace cared less about statistics than about the simple moment when a hand reached for hers and she squeezed back, whether the hand wore a Canadian tag or a German one.

After the war, Grace returned to Canada in 1946, thirty-one and exhausted from five years of relentless work. She became a nursing instructor in Vancouver and later taught in hospitals across the country. Students remembered that she spoke often about technique, but more about principles: competence without cruelty, discipline without dehumanizing. She taught that the job was to treat the patient in front of you, not the uniform he arrived in.

Letters arrived for decades. Canadian veterans thanked her for the day German rifles entered the tent and she stood her ground with nothing but a Red Cross armband and authority earned by work. German veterans sent photographs of families made possible by survival. Klaus Becker wrote years later asking to find the nurse who saved him; Grace answered, and they corresponded until his death. Friedrich Steiner mailed a photograph of himself with his wife and children, writing that he walked because she refused to treat him as less human than the man beside him.

Wilhelm Richter survived the war as well. Captured in 1945, he wrote a statement for Allied records describing the incident at the casualty clearing station. He wrote that he had seen many acts of courage in the war, but rarely moral courage like a nurse refusing to let hatred dictate who deserved care.

Grace did not romanticize what she had done. She knew that some German soldiers she saved recovered and returned to combat. The thought troubled her, and when asked later whether she regretted treating enemy wounded, she answered with a simplicity that sounded almost stubborn: “I was a nurse. They were wounded. What else was I supposed to do?”

In 1985, decades after Ortona, a joint Canadian–West German ceremony in Italy honored medical personnel who served in the campaign. Grace attended at age seventy, returning to the landscape where her choices were tested. Veterans from both sides shook her hand. One German man told her he had never met her in 1943, but he had heard her name. “You reminded us,” he said, “that even in war some people remain human.”

In later retellings, the most arresting object was not a medal or a photograph, but that leather notebook: page after page listing German names beside Canadian and British ones, the same ink, the same careful columns. It showed what the tent had already proved—medical neutrality is not a slogan; it is a practiced discipline. The Red Cross armband did not stop bullets, but it gave Grace language to insist on boundaries, and the notebook gave her proof that those boundaries were honored in action. For the wounded, it meant equal bandages. For commanders, it meant a record they could not argue away.

If the Battle of Ortona is remembered for shattered buildings and house-to-house fighting, Grace McFersonson’s story is remembered for a different kind of resistance: the refusal to let the war’s categories erase a patient’s humanity. In a tent lit by kerosene lamps, surrounded by mixed cots and scattered dog tags, a Canadian nurse made mercy a daily procedure, documented it in ink, and forced both enemies and allies to confront what medical duty truly means.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.