He Flew to Scotland to End a War, Lived 21 Years Alone in Spandau, and Died at 93 by an ‘Official’ Hanging—Then They Demolished the Garden House in 48 Hours, Leaving History to Guess._NU Flew to Scotland to End a War, Lived 21 Years Alone in Spandau, and Died at 93 by an ‘Official’ Hanging—Then They Demolished the Garden House in 48 Hours, Leaving History to Guess._NU

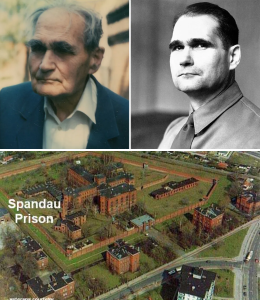

In August 1987, a 93-year-old man with severe arthritis was found dead in a small garden summerhouse at Spandau Prison in West Berlin. The official statement issued by the Allied authorities who administered the prison said Rudolf Hess had died by suicide. Yet immediately, the case attracted doubt: how could an elderly prisoner with failing health carry out a fatal hanging without help, and why was the physical setting of his death cleared and later demolished so quickly?

Hess’s last day became a magnet for suspicion, but it was only the ending of a life already marked by strangeness and contradiction. He had been one of Adolf Hitler’s earliest followers and, for a time, his public “right-hand man.” He then vanished from real influence, resurfacing in 1941 with a secret flight to Scotland that embarrassed the Nazi regime and puzzled Britain. After the war, he was convicted at Nuremberg and spent decades behind prison walls, becoming the final surviving major defendant from the tribunal and the solitary prisoner of a Cold War jail.

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess was born on 26 April 1894 in Alexandria, Egypt, into a wealthy German merchant family. His upbringing was shaped by expatriate discipline and the commerce of a colonial port, and later accounts emphasize that he admired aspects of British order and structure even as he would come to embody a movement defined by anti-British hatred. His father, a successful businessman, wanted him to enter commerce. The First World War disrupted that trajectory, as it did for an entire generation.

Hess enlisted in the German Army, served on the Western Front, and fought in major battles such as Ypres and Verdun. He was wounded and received the Iron Cross, eventually reaching the rank of reserve lieutenant. Like many veterans, he experienced the defeat of 1918 not as a political transition but as personal humiliation. The combination of loss, instability, and radical nationalist myths proved fertile ground for extremism.

On 1 July 1920, Hess joined the Nazi Party when it was still a marginal, violent movement. He became one of Hitler’s earliest adherents and quickly developed a reputation for devotion bordering on the religious. That devotion deepened after the failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, when Hitler and other conspirators were imprisoned at Landsberg. In prison, Hess served as Hitler’s secretary and aide, helping to transcribe and edit what became “Mein Kampf,” the ideological blueprint of Nazism.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Hess rose with him. He became Deputy Führer, a role that placed him high in Nazi party hierarchy and made him an important administrative figure. His signature appeared on key laws and decrees, including measures that formalized Nazi racial policy and stripped Jews of rights. At public rallies, especially at Nuremberg, he delivered speeches and performed loyalty with a ritual intensity that suited the regime’s political theater. In those years, he looked like the model subordinate: disciplined, devoted, and visible.

Yet Hess never fully mastered the ruthless internal politics of Hitler’s court. He was widely described as eccentric, rigid, and increasingly out of place among more calculating rivals. While men like Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring maneuvered for influence through propaganda and patronage, Hess often seemed to rely on the assumption that loyalty would be rewarded automatically. That assumption proved naïve. In authoritarian systems, proximity is never guaranteed, and formal rank can be hollow if gatekeepers control access.

By the late 1930s, Hess was being sidelined from major decisions. Martin Bormann, a skilled organizer, gradually took over many of his responsibilities and tightened control over Hitler’s schedule and paperwork. In such a system, the ability to decide who met the leader—and when—became power in its purest form. Hess, once indispensable, became symbolic. His public presence remained useful for ceremonies, but his influence in policy diminished.

Behind the scenes, Hess reportedly worried about Germany’s strategic position as war expanded. One concern attributed to him was the danger of fighting both Britain and the Soviet Union at the same time. As Hitler prepared Operation Barbarossa, the planned invasion of the Soviet Union, Hess convinced himself that Britain had to be neutralized first—preferably through negotiation. This belief set the stage for one of the Second World War’s most bizarre episodes: a senior Nazi leader attempting a personal peace mission.

On 10 May 1941, after several aborted attempts due to weather or mechanical issues, Hess climbed into a specially modified Messerschmitt Bf 110 at the Augsburg-Haunstetten airfield. He wore a leather flying suit and carried maps, money, and a distinctive collection of medicines and homeopathic remedies. His flight plan suggests careful preparation. He navigated toward the Frisian Islands, made a diversion intended to reduce radar detection, and then set course across the North Sea.

British radar detected an incoming aircraft and defensive measures were triggered, though interception efforts were unsuccessful. As fuel dwindled and darkness complicated navigation, Hess searched for his intended destination in Scotland: Dungavel House, associated with the Duke of Hamilton. Hess believed the Duke could connect him to influential circles who might consider peace. He had previously attempted to make contact by letter, and intelligence services were aware of unusual signals, even if they did not anticipate the precise form of his arrival.

Shortly before midnight, Hess bailed out by parachute. He landed at a farm near Eaglesham, south of Glasgow, injuring his ankle and becoming tangled in his chute. When approached by a local ploughman, he initially gave the name “Captain Alfred Horn,” but he soon identified himself as Rudolf Hess and requested to meet the Duke of Hamilton. Home Guard personnel took him into custody and he was transferred to military authorities. For Britain, the situation was both a security event and a political curiosity: a senior Nazi figure arriving uninvited, insisting he carried a message that could end a war.

Hess’s peace mission failed immediately as diplomacy. Churchill’s government dismissed the approach. Britain’s war aim was to continue resisting Nazi Germany, and the offer—whatever its details—came from a regime already committed to conquest and terror. Hess was interrogated, held as a prisoner of war, and later transferred between secure locations. His presence did, however, provoke speculation: if a man of his rank was willing to fly alone into enemy territory, what did that say about divisions within the Nazi leadership?

In Germany, Hitler reacted with fury. Publicly, Nazi propaganda portrayed Hess as mentally unstable and insisted he had acted alone. Privately, Hitler ordered that Hess would be shot if he ever returned to Germany. The regime’s reaction was shaped by fear as much as anger: allies and enemies alike might interpret the flight as evidence of splits or backchannel diplomacy. Casting Hess as unbalanced allowed the Nazis to deny responsibility, preserve Hitler’s image of control, and warn others against independent initiatives.

After the war, Hess was returned to Germany to face trial at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. His courtroom behavior became another source of fascination and confusion. He claimed amnesia for extended periods, and psychiatrists debated how much was genuine illness and how much was calculated performance. The tribunal’s chief psychiatrist described a complex condition: a neurotic presentation with paranoid and schizoid traits, and memory loss that appeared partly genuine and partly feigned.

Despite his theatrics, the tribunal convicted Hess of crimes against peace and conspiracy with other Nazi leaders. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, though some prosecutors and Soviet representatives argued he should be executed like other leading defendants. The sentence sent him to Spandau Prison, a large facility in West Berlin run jointly by the four Allied powers: the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. The prison became a Cold War institution as much as a penal one, a site where postwar justice was entangled with postwar rivalry.

Over time, the other Spandau prisoners were released. By 1966, Hess remained alone. For the next 21 years, he was the prison’s only inmate, guarded in a complex built for hundreds. The arrangement was costly and controversial. A contemporary report estimated that maintaining Spandau for one prisoner cost West Germany about $670,000 a year, a figure that invited both criticism and grim irony: a once-powerful Nazi leader kept alive and isolated at enormous expense.

Repeated campaigns sought Hess’s release on humanitarian grounds as he aged. Family members petitioned, and some politicians argued that indefinite solitary confinement was unnecessary. But the Soviet Union consistently opposed release. That stance fueled speculation that Moscow feared what Hess might reveal, or that his continued detention served symbolic purposes—proof that one major Nazi figure would never be forgiven. Whatever the motive, the result was the same: Hess lived out decades in a controlled, politicized isolation.

Isolation bred rumor. Hess developed persistent fears about poisoning and complained of chronic ailments. He was also known to have attempted suicide more than once while imprisoned, a fact later cited by authorities to support the plausibility of suicide in 1987. At the same time, his long captivity created ideal conditions for conspiracy theories. The most famous claimed the man in Spandau was not Hess at all, but a double substituted to conceal sensitive secrets about the 1941 mission.

Supporters of the “doppelgänger” theory pointed to alleged inconsistencies in scars and medical history, as well as to Hess’s odd behavior at Nuremberg. The theory persisted for decades in popular writing, partly because it offered a dramatic explanation for an otherwise bleak reality: one elderly man held alone in a massive prison, guarded by superpowers. For historians, the theory was largely speculative and unsupported, but it remained culturally powerful.

In 2019, a DNA study addressed the identity question directly. Researchers compared Y-chromosome markers from a blood sample attributed to the Spandau prisoner with those from a living paternal-line relative of Rudolf Hess. The reported statistical likelihood of close relation was 99.99 percent, strongly supporting the conclusion that the prisoner was Hess and not an impostor. The result did not resolve every mystery around him, but it closed a major avenue of speculation that had persisted for more than seventy years.

Identity, however, is not the same as explanation. The circumstances of Hess’s death remained contested. On 17 August 1987, he was found in the prison’s garden summerhouse, a small structure used as a reading room. The Four-Powers Authority announced he had hanged himself using an electrical cord. He was taken to a British military hospital and declared dead later that afternoon. A short note to his family was reportedly found, consistent with suicide.

Yet skepticism persisted for several reasons. Hess was extremely old and suffered from arthritis and other ailments. Critics questioned whether he had the strength and mobility to prepare a hanging apparatus without help. Others pointed to alleged irregularities at the scene. A medical attendant later claimed the room appeared disturbed and described the position of the cord in ways that, he argued, did not fit the official narrative. Hess’s lawyer and his son publicly suggested murder, and the son maintained that powerful states had an interest in silence.

Conflicting medical interpretations added fuel. Accounts circulated that a second examination suggested strangulation rather than classic hanging, though public documentation and access to records were limited and disputed. In a case already surrounded by secrecy, the inability of independent investigators to reconstruct events with confidence created a vacuum that speculation quickly filled. Even the smallest detail—who entered the room, what was moved, what was photographed—became politically charged.

Then came the demolition. After Hess’s death, Spandau Prison was demolished and the site redeveloped. Authorities argued the prison could become a neo-Nazi shrine if it remained. That concern was not abstract: Hess’s grave later became a pilgrimage site for extremists until authorities removed it and destroyed the marker. Seen from that perspective, demolition was an attempt to prevent ritualization. But demolition also erased the physical environment of the death, eliminating the possibility of new forensic reconstruction and ensuring that competing narratives would persist.

The historical context mattered. Hess died during a period when Cold War politics were shifting. Gorbachev’s reforms raised the prospect that Soviet archives might open and that long-classified wartime files could become public. As the last surviving major defendant from Nuremberg, Hess represented a living link to internal Nazi decision-making and to the strange diplomacy of 1941. His death also resolved a diplomatic and financial headache: the awkward international arrangement of guarding one prisoner for decades.

For historians, the most responsible approach is to separate the established timeline from the unresolved debate. It is established that Hess was a leading Nazi official, Deputy Führer, and participant in a criminal regime. It is established that he flew to Scotland on 10 May 1941, was captured, and spent the remainder of the war in British custody. It is established that he was convicted at Nuremberg and served a life sentence at Spandau, where he was the only prisoner for decades. It is established that he died in 1987 under an official ruling of suicide.

Beyond that, uncertainty begins. Historians still debate what Hess truly hoped to achieve in 1941 and whether any significant British figures were aware of his approach in advance. Intelligence files remain partly classified or were released in incomplete form, leaving room for competing interpretations. And while the DNA study undermined the doppelgänger theory, it did not prove or disprove murder in 1987. The death remains controversial largely because the physical evidence was limited and the setting was erased.

Hess’s life is therefore remembered less for redemption than for unresolved questions. His early devotion to Hitler helped bring a destructive ideology into power, and his later attempt at a private peace mission did not erase his responsibility. Yet his story also reveals how authoritarian systems consume their own. Loyal followers can be discarded when they become inconvenient, and gatekeepers can turn proximity into domination. In that sense, Hess was both perpetrator and cautionary example: a man who embraced a murderous regime and then discovered that, within it, loyalty did not guarantee protection.

In the end, Spandau did not merely imprison Hess. It preserved him in a Cold War glass case, watched by competing powers, until the moment he died and the physical prison was wiped away. The disappearance of the place did not end the debate. It ensured that, for many, the last question remains the loudest: not what Hess believed, but what happened in that small summerhouse when history’s most isolated prisoner died.

Hess’s prewar persona included a fixation on alternative medicine and mystical thinking, traits that later colored how observers interpreted his conduct. Colleagues described him as suggestible and prone to rigid, repetitive ideas. The fact that he carried homeopathic remedies on his Scotland flight became a shorthand for this eccentricity. It does not excuse his political actions, but it helps explain why rivals found it easy to dismiss him as strange once his usefulness declined.

The Scotland mission also remains debated in motive. Many historians view it as a personal fantasy: an isolated deputy imagining he could bypass governments and “solve” a war. Others treat it as a calculated bid to regain relevance by delivering what Hess believed Hitler needed—British neutrality before the Soviet invasion plan. A smaller camp argues that Hess may have been encouraged by intermediaries or misled by rumors of anti-Churchill influence in Britain. The surviving record supports careful planning of the flight but provides less certainty about the political assumptions behind it.

That tension—between a documented flight and an undocumented political context—keeps the episode alive. Each newly released memo or diary fragment reshapes the story without settling it, and uncertainty becomes the space where myth grows.

At Nuremberg, Hess’s behavior blurred the line between pathology and strategy. His amnesia claims, later partly withdrawn, complicated questioning and allowed him to occupy a peculiar role in the courtroom: present, but difficult to pin down. Psychiatrists offered clinical diagnoses, yet the proceedings were also political theater, and appearing unstable could function as a shield. At the same time, accounts from captivity suggest he genuinely feared poisoning and suffered anxiety and paranoia, patterns that intensified under confinement.

Spandau’s daily routine was strict and monotonous, designed to prevent escape and to avoid giving prisoners the aura of celebrity. When Hess became the sole inmate, the system turned surreal. The prison was administered jointly, with the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union rotating guard duties. Even small decisions—medical visits, building repairs, visitation procedures—could become diplomatic disputes. Hess was permitted limited exercise and garden time, which later included access to the summerhouse reading room.

The refusal to release him, especially the Soviet veto, became a political symbol in its own right. Supporters of release argued that an elderly man in failing health posed no danger and that continuing solitary confinement served no justice. Opponents insisted that the last surviving major Nuremberg prisoner embodied accountability, and that release could invite extremist celebration. The cost and awkwardness of maintaining one prisoner for decades made the controversy sharper, and it guaranteed that his name would outlive the prison that held him.

Spandau’s demolition after Hess’s death was publicly justified as prevention: remove a site that could attract neo-Nazi pilgrimage. The concern proved real; Hess’s grave later became a rallying point until German authorities removed it. Yet demolition also erased the physical setting of the death, foreclosing independent reconstruction and ensuring that competing narratives would persist. In that sense, Hess remains less a man than a historical pressure point, where secrecy, propaganda, and memory collide.