The river looked almost peaceful.

From the high bluff where the observation post had been scraped out of the mud, the Rhine spread out in a wide, gray sweep under the March sky, the current sliding past in long, muscular ripples that tugged at the scattered debris drifting along its surface. A thin mist hung over the water, softening the far bank into a darker smudge. Somewhere on that far side, Germany was dying—but it wasn’t dead yet.

It was March 23rd, 1945, and for four long, brutal years this river had been more than a line on a map. The Rhine was the psychological wall of the Third Reich, the last great moat before the heartland. In every German’s imagination, it was sacred, storied in legend and song. In the imagination of Allied planners, it was something else entirely: the last obstacle. Once that river was crossed in force, once armor and supply columns poured over it, the war in Europe would not simply be turning—it would be ending.

On the north bank, in a sprawling tented city of command posts, supply dumps, and carefully arranged artillery positions, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was getting ready to write his name into that history.

Montgomery’s war had always been tidy, in its way. He believed that battles were problems to be solved, equations with variables that could be controlled if you were careful enough, cautious enough, methodical enough. Now, on this gray March day, he was standing in front of the grandest equation of his career.

He had a million men. That number meant something to him. It had weight. A million men in crisp tables on a situation map, a million men sorted into divisions and brigades and battalions. He had nearly three thousand artillery pieces, each carefully sited, carefully registered on every possible target on the far bank. He had air support scheduled in precise blocks. He had a massive airborne assault ready to drop behind German lines. He had press officers, and official photographers, and carefully worded communiqués prepared for release.

He had, most importantly, the eyes of the world.

Montgomery stood in his command caravan, that odd combination of Spartan military order and British domestic comfort, and listened while a staff officer read out the latest meteorological report. Wind direction. Cloud cover. Visibility over the drop zones. Everything, everything, had to be right.

He was the hero of Britain, the man of Alamein, the savior who had given his country its first clear victory against the Germans in North Africa. The British public had endured the Blitz, rationing, years of grim news. They were tired, and they wanted not just the end of the war, but a moment—one great, shining moment—to justify all of it. Churchill knew that. The newspapers knew that. And Montgomery knew that better than anyone.

He needed this crossing.

That was why, weeks earlier, he had argued, cajoled, and finally demanded that the American armies around him stop. Not forever. Not even for long, not on paper. Just long enough for him to assemble his masterpiece.

Fuel, ammunition, bridging equipment—all of it, he insisted, should be diverted north, to his sector. He pushed the idea hard in meetings, in memos, in cable traffic. The Americans, he argued, were too spread out, too impulsive. Their generals liked to dash here and there, burning fuel, grinding down their supplies for local advantage.

This crossing, he argued, was not the time for improvisation. This crossing had to be controlled. It had to be his.

General Dwight Eisenhower, weary, steady, perpetually balancing egos as much as armies, listened. He listened to Montgomery, and to British political pressure, and to the quiet, increasingly impatient Americans around him. He listened and he did what he had been doing since 1942: he chose compromise. The American advance would be paused. Across from the Rhine, formations already poised on its west bank would hold their places, conserve fuel, and wait for Operation Plunder, Montgomery’s grand assault.

A cable went out, with the calm finality that only a few lines of text can have. To the commander of the American Third Army it was very simple: hold your positions. Do not cross the Rhine. Support Montgomery’s plan.

The cable went out. The words reached a headquarters a little farther south, where a very different kind of general was pacing like a caged animal.

George S. Patton could not stand still.

He moved restlessly around the room that served as his forward command post, the heels of his polished boots clicking against the rough wooden floor. A map of the Rhine lay spread across a trestle table, its folds weighted down with coffee mugs, a stray wrench, and the butt of a .45. Colored chinagraph lines and pins traced the Third Army’s advance to date. Units were marked where they had paused, obediently, under Eisenhower’s orders.

Patton stared at the river line, his jaw working, his fingers tapping on the map. Outside, trucks rumbled past in the mud, engines backfiring, men shouting briefly and then fading away as the convoy moved on. Somewhere a generator coughed into life, then steadied to a drone.

He glanced up at the wall. Somebody—one of his staff officers, perhaps—had tacked up a clipping of a British newspaper, its headline praising “Monty’s Master Plan.” Another sheet held notes from SHAEF about fuel priorities and the need for “coordinated action.”

Patton’s lip curled.

Coordinate. Wait. Support.

He remembered Sicily. He remembered standing on a makeshift podium in Messina, the dust of the march still on his boots, while a British column marched in with bagpipes skirling, expecting to find an empty city, expecting to be greeted as conquering heroes. He remembered Montgomery’s face as he rode in, raised chin, stiff posture, only to see Patton already there, already receiving the salutes, already claiming the prize.

Patton had beaten him there by hours. Hours that stung like a lifetime.

Montgomery had never forgotten that moment. Neither had Patton.

They were opposites, everyone said so. Monty with his crisp beret and carefully composed set-piece battles. Patton with his gleaming helmet, his ivory-handled pistols, his obscene vocabulary, and his sermons on aggression. One was a quiet mathematician of war. The other was a cavalryman from another century, reborn into the mechanized age.

Oil and water, the staff officers joked. They weren’t wrong. And now, once again, fate had drawn a neat line between them: a river that only one of them could truly claim in the eyes of history.

Patton leaned over the map, his finger tracing the course of the Rhine around a small dot labeled Oppenheim. He thought of what he had seen these last weeks: German units falling back in ragged disorder, columns of prisoners with hollow eyes, bridges blown in haste and sometimes not at all. The Wehrmacht was still dangerous in places, still capable of sudden, fierce resistance—but the structure was cracking. Messengers weren’t arriving. Orders weren’t being obeyed. The great enemy that had seemed untouchable in 1940 was now a wounded animal losing blood by the hour.

He knew what time meant now. Every day—every hour—lost to caution was a gift to the defenders on the far bank. Give the Germans a few more weeks, and they would dig in along the east side of the river, plant mines and guns and barbed wire, set up interlocking fields of fire, call in reserves from wherever they could scrape them together. Crossing then would be a butcher’s bill written in thousands.

To Patton, the logic was brutal and simple: If you can cross now, you cross now.

He straightened up and turned to the small knot of officers clustered near the doorway. They had been waiting for this, watching the anger build in their commander’s tight shoulders, in the way his jaw clenched whenever someone mentioned “holding for Monty.”

Major General Walton Walker, commander of XX Corps, stood with his arms folded, a cigarette burning low between his fingers. General Manton Eddy, of XII Corps, sat on the edge of a field chair, one boot bouncing. A couple of colonels hovered nearby, notebooks ready, trying not to look too openly anxious.

“Gentlemen,” Patton said, his voice clipped but controlled. “We’ve been ordered to sit still and wait while the British put on their show.”

No one said anything. The men shifted, glanced at each other, waited.

Patton’s eyes glittered.

“I’m not going to do it.”

The words fell into the silence like stones dropped into deep water.

Walker looked down, exhaled smoke slowly through his nose. Eddy’s boot stopped bouncing.

Patton stabbed a finger at the map, at that little bend near Oppenheim. “The Krauts are running,” he said. “They’re falling back in ones and twos. They’re blowing bridges when they can, but half the time they don’t have the charges. We wait for Monty’s opera, and they’ll have time to get their act together. They will make us pay for every yard of that bank. They’ll make our boys crawl through fire.”

He took a breath, then another, forcing his tone to remain even.

“I’ve had orders from Ike,” he went on. “So have you. ‘Do not cross the Rhine.’” He spat the phrase as if it tasted bad. “Fine. We won’t cross it—officially. Not yet. We will, however, reconnoiter it.”

Walker’s eyes narrowed. “Reconnoiter, sir?” he asked cautiously. He had known Patton long enough to be wary of innocent-sounding words.

Patton’s expression turned into something like a grin, sharp and predatory.

“Reconnoiter,” he repeated. “I want a reconnaissance in force. I want our boys to go down to that river and find out just how soft the Krauts are on the far bank. If they find a good place to put in a bridge, they’ll let me know. If they find the enemy asleep, they won’t wake them.”

He let the implication hang in the air.

Eddy cleared his throat. “How big a reconnaissance, sir?”

“The Fifth Infantry Division,” Patton said briskly. “All of it. And I want engineers up front. Bridging equipment ready. Boats ready. I don’t want to find out in two days that we could have crossed last night.”

He paused, then added, “Make sure the word ‘crossing’ doesn’t appear in any orders. ‘Reconnaissance in force.’ That’s all. We’re obeying the letter of Ike’s instructions, if not the spirit.”

Walker’s cigarette had burned down to the filter. He crushed it out slowly in a tin ashtray.

“Bradley won’t like this,” he said.

Patton shrugged. “Brad’s a good man. He’ll understand if it works. If it doesn’t…” He spread his hands. “If it doesn’t, we’ll have a few patrols shot up and everyone will say, ‘Well, at least Third Army was aggressively reconnoitering.’”

“And if it does work?” one of the colonels asked, unable to help himself.

Patton looked at the river line again. His voice lowered, grew almost soft.

“If it works,” he said, “we end the war that much sooner. And when Monty walks up to his nice, shiny bridge with the cameras rolling, he’ll find out he’s late to his own party.”

Outside, someone shouted that the command car was ready. Patton nodded once, decisively.

“Get it done,” he told them. “Tonight.”

The sky that evening closed in low and thick, a lid of cloud that turned the world into shades of charcoal and slate. Along the west bank of the Rhine near Oppenheim, the darkness grew heavy and damp. The wind rolled in faint gusts off the water, carrying with it the cold wet smell of the river.

Men moved like shadows along the bank.

They were infantrymen of the Fifth Division, their faces blackened, their gear strapped tight to avoid any rattling. Helmets were pulled low. Rifle slings had been wrapped in cloth. Words were spoken in whispers, and even those were rare. The river made its own voice: a constant, rushing murmur punctuated by the occasional splash of driftwood or the clunk of something unseen against the bank.

Pale shapes loomed at the water’s edge: assault boats, light and narrow, their metal skins cold to the touch. Engineers moved among them, checking tie-downs, counting paddles, quietly assigning men to boats.

Lieutenant Harry Collins—twenty-three years old, more tired than he had known a man could be, and old enough now that he had stopped counting how many of his friends he’d buried—stood with his squad in the lee of a shattered farmhouse wall, watching the preparations.

“Looks like we’re really doing it,” one of his men murmured, breath steaming in the cold air.

Collins nodded once. He had heard, through the murky grapevine of army rumor, that “higher up” didn’t want them crossing yet. Something about the British. Something about politics. None of it mattered here, on the cold riverbank where his fingers had gone numb inside his gloves, and his helmet strap rubbed against the stubble on his jaw, and his stomach gnawed at itself because the last hot meal had been days ago.

All that mattered was that someone had decided that tonight, these particular men would slip into those particular boats and cross into Germany’s last sanctuary.

He looked at the far bank. It was just darkness. Somewhere over there were German sentries—maybe. Maybe not. Intelligence reports were contradictory: some said the enemy had pulled back; some said they were still there in strength. Collins knew better than to trust any of it. The only truth was the first time you saw muzzle flashes aimed in your direction.

An engineer captain came down the line, his red-lensed flashlight hooded, his voice low but firm.

“First wave,” he said. “Listen up. You know your jobs. No talking once you’re in the boats. Paddles only—no outboard motors until we’re sure the far side is quiet. If you take fire, you hug the deck and we keep going. If a boat flips, you swim. The current’s strong but the distance isn’t that far. You trained for this.”

He sounded confident. Collins was grateful for that. Confidence was a kind of currency out here. You pretended to have it so the men around you would have it, and they pretended for you in return. Together, you bought the courage to step into the unknown.

The captain moved on. A sergeant waved Collins’s squad forward toward the boats.

They clambered down the muddy bank, sliding and catching themselves, boots sinking into the cold, wet earth. The boats rocked as they stepped into them, water slapping softly against the hulls. Collins took his place near the bow, fingers tightening around the shaft of his paddle.

“Ready,” someone whispered.

A whistle, very soft, very brief.

Then they were off.

The river accepted them with a quiet, deadly indifference. The current gripped the little boats and dragged at them as men leaned into their paddles, muscles straining silently, breath coming in sharp bursts. The mist closed in. The west bank receded behind them into darkness. The east bank loomed ahead, a low, darker line that seemed maddeningly far away and yet dangerously close at the same time.

Collins’s arms burned. He forced himself to keep his stroke smooth, steady, matched to the men beside him. He could hear water dripping from paddles, the faint creak of strained metal. He could hear his own heartbeat, loud in his ears.

He listened for the other sound he was sure he’d hear at any second: the ragged, vicious ripping of machine gun fire.

Nothing.

The river slid beneath them. One boat, slightly downriver, drifted closer than it should; someone corrected softly. Behind them, another wave of boats pushed out, their shapes barely visible in the gloom.

Collins risked a glance upward. The clouds were a low, featureless ceiling. No stars. No moon. No help.

Please, he thought, though he could not have said to whom he was speaking. Just let them be asleep. Let them be gone. Let them be anything but ready.

The east bank swelled in front of them now. He could see brush. The dark teeth of tree roots. A faint, pale strip of mud where the water lapped.

“Easy,” he hissed. “Easy. Get ready to jump.”

The bow grated softly against mud. The boat rocked as men shifted.

“Go,” Collins whispered. “Go, go.”

He jumped, his boots sinking into cold, sucking muck up to the ankles. He lunged forward, hauling the boat farther onto the bank so the others could spill out behind him. Men scrambled, slipping, cursing under their breath. Rifles swung into hands. Eyes strained into the darkness of the tree line.

Somewhere a dog barked once, far off, then stopped.

No challenge. No shot.

Collins felt eerie disappointment under the relief. The empty bank made the enemy seem more ghostlike. He would almost have preferred something clear: tracers, shouts, the sharp certainty of being under fire. This silence felt like a hand reaching calmly out of the dark to close over his throat.

“Form up,” he breathed. “Two files. Up the bank.”

They moved, low and quick, hunched shapes sliding into the sparse cover. A tangle of bushes scraped at trousers. A piece of broken fencing snagged on a pack. Someone stumbled, swore softly, rose again. The line of trees gave way to a gentle slope.

Collins lifted a clenched fist. The column halted.

Ahead, a vague shape—maybe a figure?—stood against the pale sky, its outline blurred by the mist. Collins sank to one knee, rifle coming up, breath held.

“Wer da?” a tired voice called softly in German.

Collins’s finger tightened on the trigger. Then instinct and training overlapped and he snapped out, in halting German, “Patrouille. Nicht schießen.” Patrol. Don’t shoot.

The figure hesitated, then took two lazy steps forward. As it did, dim light from a shielded lamp behind it caught on the edge of a helmet.

Collins fired.

The helmet jerked, the shape crumpled. There was a shocked, sharp cry from somewhere off to the right.

“Los! Amis!” another voice shouted, suddenly desperate.

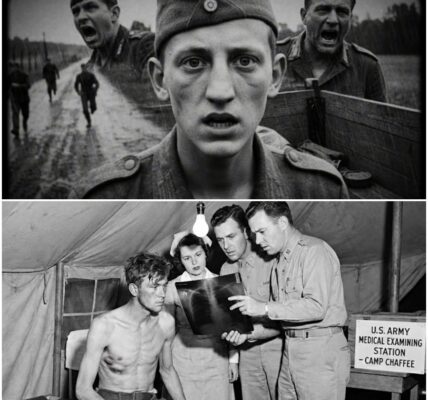

The bank exploded into motion. American rifles chattered in short, controlled bursts. Figures bolted from foxholes nearby, some still pulling on boots, some without weapons in their hands. Two Germans went down, arms flung wide. A third dropped his rifle and fell to his knees, hands up.

It was over in seconds. The shouting faded. A moan somewhere was cut off by a quick, practical command for a medic.

Collins exhaled slowly, his lungs burning. He looked around at the little patch of German soil they’d seized: a muddy slope, a few shallow dugouts, a pair of stunned, barely awake sentries.

“That’s your security, huh?” one of his men muttered. “Hell of a last line of defense.”

Once the first thin foothold had been taken, the rest followed with startling speed. More boats slid across the river, guided by engineers whose mouths were dry and whose eyes burned from lack of sleep. Battalion after battalion scrambled up the muddy bank, rifles at the ready, expecting always the long, rolling roar of enemy artillery that somehow never came.

By midnight, six battalions of the Fifth Division were on the far side, pushing cautiously inland, expanding the bridgehead. German resistance remained fitful, disorganized. Small groups of defenders fired from windows, from tree lines, from half-dug trenches, and were swept aside by the momentum of the American advance.

Back on the west bank, another group of men had begun their own grueling battle—this one with steel, current, and time.

The engineers worked like men possessed.

Under hooded lamps and flickering, dimmed headlights, they wrestled with massive pontoons, hauling the heavy sections into place along the bank. Bulldozers growled as they scraped ramps into the mud. Trucks backed up with their loads of bridging equipment, tires spinning briefly in the muck. The smell of exhaust and sweat and cold river air mingled in a sour, metallic taste.

Captain Jack Morris, commander of one of the bridging companies, had long since stopped feeling his feet. He barked orders over the din, the words coming out hoarse and clipped.

“Get that pontoon upriver—no, damn it, upriver, or the current’s going to swing it out of line! I want that anchor cable tight enough to sing. You—yes, you—get me another set of bolts; we’re short on the joint.”

Above them, the sky’s low lid of cloud glowed faintly now and then as distant artillery fired—British guns, mostly, far to the north, testing their registration. Occasionally, the whine of an engine would drift overhead and men would freeze, staring upward, wondering if this time the Luftwaffe really would appear and rake their half-finished structure with bombs and machine gun fire.

But the sky remained empty. The German Air Force, like the German Army, was a shadow of what it had been.

Morris moved along the growing line of connected pontoons, his boots ringing on the metal decks. Each section was linked to its neighbor with heavy hinges. Between them lay the promise of a road—a road that, if completed, would bear tanks, half-tracks, supply trucks, the whole roaring steel lung of the Third Army.

“Faster,” he urged his men. “We don’t know when higher headquarters is going to notice what we’ve done. I want armor rolling before anyone decides to get nervous.”

Cold water splashed up onto the pontoons, soaking trousers and socks. Hands, already raw from days of work, blistered anew under the strain. But the bridge grew, foot by foot, yard by yard, extending out over the swift water.

Just before dawn, in a muddy command post not far from the river, a field telephone trilled.

Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, reached for it, rubbing at his tired eyes with his free hand.

“Bradley,” he said.

From the other end of the line, a familiar voice snapped through, alive with a barely suppressed excitement that Bradley recognized at once.

“Brad,” George Patton said without preamble. “Don’t tell anyone, but I’m across.”

Bradley blinked. He was not yet fully awake; the night’s brief sleep had been troubled by staff estimates and casualty reports. “Across?” he echoed. “Across what, George?”

“The Rhine,” Patton replied, his tone almost impatient. “I sneaked a division over last night. Oppenheim. There are so few Krauts there they don’t even know it yet. So don’t announce it. If you announce it, the Nazis will wake up and start shooting.”

Bradley sat up straighter, fatigue dropping away like a cloak. “You crossed the Rhine?” he said slowly. “George, Monty is scheduled to launch his operation tomorrow. Operation Plunder. He’s expecting to make the first crossing in force.”

There was a brief, crackling silence as the signal bounced along its miles of wire.

“Well,” Patton said at last, a dry chuckle in his voice, “he’s a little late. I have a bridge operational. I have tanks moving. And, Brad, I want you to tell the British something for me.”

Bradley closed his eyes briefly. He could see the headlines already, could hear the grinding of teeth in the British press office. “What, George?”

“Tell them I’m keeping it a secret so I don’t embarrass them,” Patton said. “But tell them the Third Army is walking across the Rhine while they’re still getting their equipment ready.”

Bradley almost laughed, despite the ache building behind his eyes. He could imagine Montgomery’s reaction to that message all too clearly.

“George,” he began carefully, “Ike’s orders were—”

“I know what Ike’s orders were,” Patton cut in. “I obeyed them—more or less. I took a little reconnaissance in force. Turns out the far bank was asleep. I’m not going to sit here polishing my boots while that little Brit steals the war.”

“Just keep a lid on it for now,” Bradley said. “No press, no grandstanding. We’ll handle Montgomery.”

“You have my word,” Patton said, and Bradley was not entirely reassured by that. “No press,” the general added. “Well… not yet.”

He hung up and walked outside.

Dawn was riming the eastern sky with a faint, dirty pink. The air bit at his cheeks. Somewhere in the near distance, he could hear the clank and grind of tracks on metal. The pontoon bridge was finished enough, at least in its first span, to begin testing.

Patton strode toward the river, boots splashing in shallow puddles. A small entourage of aides and staff officers trailed after him, trying to keep up. He wore his steel helmet, polished and strapped just so, and the ever-present pistols at his hips. Mud spattered his trousers, but he did not seem to notice.

When he stepped onto the bridge, the steel decking vibrated faintly under his weight. Ahead, the first tank was nudging forward—a Sherman, its turret turned slightly to the side, tracks grinding slowly over the join between two pontoons. The engineers watched it with held breath, ready to shout orders if the structure shifted in any ominous way.

“Beautiful,” Patton murmured, almost to himself. “Beautiful.”

He walked steadily toward the center of the span. Cold wind came up off the water, tugging at his jacket. Below, the Rhine surged and rolled, thick and indifferent.

He stopped in the middle, turned, and held up a hand. The tank driver, staring through his vision slit, saw the gesture and brought the machine to a clanking, squeaking halt. The sound of its idling engine shuddered through the air.

Men on both banks paused to watch. Soldiers stood still at the approaches. Engineers leaned on wrenches. A few officers, hearing that Patton had gone out onto the bridge, had followed at a distance, curious.

Patton put his hands on his belt, gaze sweeping the river. This, he knew, was more than a practical crossing. This was a symbol. The Rhine meant something to the Germans—something wrapped up in myth and pride and all the toxic dreams of empire that had brought them to this ruin. To walk over it unopposed was already an insult. But Patton was a man who understood the theater of war.

He was, in his own way, a performer.

With hundreds of eyes on him, he unbuckled his belt, unbuttoned his fly, and, without a word, urinated into the Rhine.

A ripple of laughter, shocked and delighted, ran along the bridge and the banks. The wind carried the sound away downstream.

Patton zipped up again, his expression utterly serious, as if he had just carried out some solemn ceremony.

“I’ve been looking forward to that for a long time,” he said to no one in particular, though several aides stood close enough to hear. Then, louder, with a sudden grin, “Send a picture of this to Eisenhower.”

An enterprising photographer, quick on the draw, had already raised his camera. The click of the shutter was almost lost in the engine noise.

Patton waved for the tank to continue. The Sherman rumbled forward again, clattering over the steel plates, heading into Germany.

Behind it, more vehicles were lining up: trucks loaded with infantry, jeeps, armored cars. The bridge flexed and hummed under the growing weight, but it held. The Third Army, in defiance of timetables and official plans, was pouring into the east.

Far to the north, Montgomery’s preparations continued.

In his command caravan, the field marshal went over the latest schedule for Operation Plunder. Drop zones. H-hour. Artillery programs. The air was thick with cigarette smoke and the smell of coffee. Maps lay in layered sheets on the table, each one covering a narrower slice of the river line, each annotated in painstaking detail.

He knew that American units had been probing the river. Everyone knew that. Reports filtered in daily of patrols sent down to the bank, of small skirmishes, of attempted crossings that had been repulsed or had succeeded in only minor ways. It did not trouble him unduly. Local initiatives were to be expected. What mattered, in his view, was the grand design.

Behind his thin, sharp features and bright eyes, Montgomery harbored a bitter memory of Messina. He had been promised center stage there, and Patton had snatched it with a mix of disobedience and audacity. That would not happen again. Not this time. Not on the Rhine.

Plunder would be too large, too public, too central to the Allied timetable. The newspapers were already primed. Churchill himself would be present. The world would watch airborne troops dropping from the sky in their thousands, watch British and Canadian divisions driving over the river under a thunder of guns. It would be, he told himself, the culmination of his career.

On the morning of March 24th, he would give the signal, and history would be his.

On the morning of March 24th, the signal was indeed given.

Guns that had sat silent, muzzles dark against the pale sky, erupted in flame. The ground shook under the continuous crash. Along the riverbank, smoke screens billowed, rolling out in thick, chemical clouds to cover the movements of assault boats and amphibious vehicles. Above, the sky filled with aircraft, engines droning in layered choruses as they flew toward drop zones behind German positions.

Paratroopers, weighed down with equipment, shuffled along the interiors of lumbering transport planes, the green light above the door flicking on. “Go! Go!” their jumpmasters shouted, and they plunged into cold air, chutes snapping open, the sky suddenly filled with white silk mushrooms drifting down toward fields and forests.

Churchill would later describe it in glowing terms, the spectacle of it, the power and coordination. It was, by any conventional military measure, a well-executed assault. Bridges were seized. High ground was taken. German resistance, alerted by the preliminary bombardment, fought back with everything it could muster, but it was not enough.

The Rhine was crossed in force.

And yet, as Montgomery toured his sectors, watching his men push forward, something sour lurked at the back of his mind.

News traveled quickly in wartime, whether officially sanctioned or not. Talk about Patton’s crossing began as murmurs in staff corridors, as remarks in mess tents, as gossip traded between liaison officers in smoky anterooms.

“Did you hear?” someone would say. “Third Army’s already across. Tanks and everything.”

“Nonsense,” another would reply. “Not officially. Not in strength. Just local efforts.”

“Local efforts with bridges and armored divisions,” the first would say dryly.

By the time a British briefing officer arrived at Patton’s headquarters to “coordinate” the upcoming operations on March 24th, the reality was impossible to ignore.

The officer, a major with the neat mustache and self-conscious crispness of his class, stepped into the American command post with a leather folder tucked under his arm. He had his orders, his talking points, his carefully prepared map overlays showing where British forces would permit American bridging operations once the “primary crossings” were in place.

He expected to find American staff officers still planning their own river assault. Instead, he found a room humming with a different energy.

Maps on the walls were already marked with unit symbols on the far bank. Dispatch riders came and went with mud on their boots and rain on their coats. Radios crackled with traffic that spoke of towns inland, German road junctions, contact reports from units east of the river.

In the center of it all stood George Patton, his jaw set, his eyes bright. Mud flecked his boots. His helmet still bore marks from the fine spray of the river.

The British major cleared his throat, stepped forward, and saluted.

“General Patton, sir,” he began. “Major Fletcher, from Field Marshal Montgomery’s staff. I’ve been sent to coordinate our respective crossings of the Rhine. The Twenty-First Army Group’s plan is to—”

Patton held up a hand, cutting him off without ceremony.

“Major,” he said, “I think you should know that I already have three bridges across the Rhine, and I’m currently moving my Second Armored Division over them.”

Fletcher blinked. For a moment, the practiced phrases on his tongue simply vanished.

Patton went on, his tone almost genial.

“So you can tell the field marshal he can cross wherever he damn well pleases,” he added. “As long as he stays out of my way.”

The British officer opened his mouth, closed it, then managed, “I… see, sir.”

He did not see, not really—not yet. Only later, as he rode back toward Montgomery’s headquarters, would he begin to grasp the implications. The river that was supposed to be the stage for a British-managed climax had already been crossed elsewhere, in a way that would not easily be erased from the record, no matter how many carefully worded communiqués were issued.

Patton’s crossing at Oppenheim had cost his army twenty-eight casualties. Twenty-eight men killed, wounded, or missing. It was a grief for their comrades, for their families, as every loss was. But set against the scale of the war, it was astonishingly light.

Montgomery’s operation, conducted with every advantage of planning and preparation, cost the British thousands.

Historians would later analyze the reasons in long, sober paragraphs—surprise versus preparedness, the impact of preliminary bombardment on German readiness, the distribution of enemy forces at different points along the river. They would debate the ethics of Patton’s disobedience, the risks he took with his men’s lives, the strain he placed on Allied unity.

For the soldiers who had paddled across in the dark at Oppenheim, who had scrambled up a muddy German bank expecting to die and found instead a handful of sleepy sentries, the question took on a simpler shape.

Speed had saved them. Audacity had spared them the storm of artillery and machine-gun fire that would surely have greeted a heavily announced, well-advertised attempt days later.

In his diary that night, Patton wrote with a tone that mixed triumph and sardonic amusement. The Twenty-First Army Group, Montgomery’s command, he noted, was supposed to cross tomorrow. “I hope they make it,” he scribbled, “but we made it first.”

He did not need to spell out exactly whom that observation was aimed at.

Years later, when the war was over and Europe was rebuilding, the river at Oppenheim flowed on as it always had, indifferent to the blood that had been spilled along its banks. The crossings left their mark in concrete and steel, in road networks and old photographs, in the fading memories of men who had been young then and were old now.

Near the river, a small monument was erected. It spoke in simple, dignified words of the American Third Army, of the engineers and infantry who had crossed the Rhine here in March 1945. It did not mention the rivalry between Montgomery and Patton. It did not describe a British field marshal’s grand plan being overtaken by an American general’s impatience. It did not record the moment when a man in polished boots and a gleaming helmet had turned the sacred river of German legend into the butt of a crude joke and a defiant symbol.

But those who studied such things, who pored over after-action reports and diaries, who listened to old men’s stories over coffee and tape recorders, knew that the bridge at Oppenheim had been more than a structure of steel and wood.

It had been, in its own way, a statement.

While some made war a matter of perfect plans, others believed in seizing the moment with both hands, rules and rivalries be damned. While some sat for press conferences to explain how difficult the crossing would be, others slipped silently into the water and found that the hardest part was over before anyone else had finished talking about it.

On that cold March morning, when Patton stood at the center of that trembling pontoon bridge and looked down at the swirling gray Rhine, he was not thinking of political repercussions or of how history would judge him. He was thinking, as he often did, in the blunt, unvarnished terms of a soldier who had seen too many young men die because someone, somewhere, had hesitated.

He relieved himself into the river, zipped up, and smiled.

The war would grind on for a few more cruel weeks. There would be more battles, more last-ditch German defenses, more villages to fight through, more bridges to seize. Hitler would rage and issue orders nobody obeyed. Refugee columns would clog the roads. Concentration camps would be found and liberated, revealing horrors that rendered all arguments about glory and ego trivial by comparison.

But on the night of March 22nd–23rd, 1945, on a stretch of river near a small German town, the question of who had crossed the Rhine first in strength had been settled.

Not with a press release, not with a mathematically perfect timetable, not with a carefully arranged photograph of a prime minister in a bowler hat watching the proceedings.

It had been settled in the dark, in the splash of paddles, in the grunt of men hauling pontoons against the current, in the grimy smiles of engineers tightening the last bolts by feel, in the dry laugh of a general on a field telephone telling his friend, “I’m across,” when by all rights he should still have been waiting.

And it had been settled, in a way that no history book could quite capture, by a small, defiant stream of urine arcing from the bridge into the sacred river of Germany—a gesture as crude as it was clear.

While you were planning, it said, I was doing.