Auschwitz’s “Angel of Death”: Josef Mengele and the Weaponization of Medicine

On the railway ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, death could be delivered with the smallest gesture. A hand moved left, and a family disappeared into the machinery of murder. A hand moved right, and a prisoner entered a system of forced labor where hunger, disease, and exhaustion carried out a slower destruction. Survivors remember this ramp not only for the crowds and the barking orders, but for the calm routines that made catastrophe feel like a schedule.

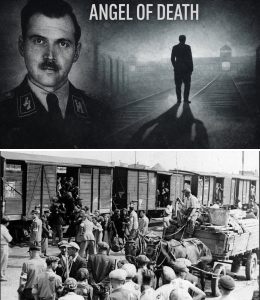

Among the SS physicians who performed selections, one name became a symbol. Josef Mengele was later called the “Angel of Death” by many who survived. He was not the only doctor at Auschwitz, and he did not invent the camp system. Yet his presence on the ramp, his fixation on certain prisoners, and his use of the camp as a laboratory made him one of the most notorious figures in the medical crimes of the Holocaust.

What makes the story especially chilling is not merely the violence, but the way it was wrapped in professional language. Mengele had degrees, credentials, and the polished manner of an educated man. He understood the outward symbols of medicine: white coats, examinations, charts, measurements, diagnoses. At Auschwitz those symbols became tools of domination. Healing was replaced by calculation. The patient was replaced by the specimen. The clinic was replaced by the camp.

Mengele was born on 16 March 1911 in Günzburg, Bavaria, into a prosperous family. His father owned a successful company manufacturing agricultural machinery, and the household’s status provided stability and opportunity. In the Germany of the interwar years, ambition could be rewarded with education, and Mengele pursued academic achievement with intensity.

He studied medicine and physical anthropology, earning advanced degrees before the Second World War. In another context, the combination might have led to an ordinary scientific career: research posts, publications, lectures, and respectable hospital work. Nazi Germany, however, turned certain sciences into an ideological battleground. Racial theory presented itself as biology. Eugenics was framed as progress. Careers advanced fastest when they served the state’s worldview.

In 1937 Mengele joined the Nazi Party, and in 1938 he joined the SS. These were not neutral affiliations. The SS fused bureaucracy with brutality and offered ambitious men a ladder of power and protection. Inside that structure, “research” could be used to justify persecution, forced sterilization, and murder. Ideology did not distort medicine by accident; it demanded that medicine participate.

In May 1943 Mengele arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Auschwitz was both a vast complex of concentration and forced-labor camps and a center of mass killing. It became the largest killing site of the Holocaust, where Jews were murdered on an industrial scale, and where many other groups—including Roma—were persecuted, imprisoned, exploited, and killed. The camp’s purpose was not rehabilitation or detention. It was destruction, carried out with administrative order.

Selection was the hinge on which that system turned. Trains arrived packed with people from across occupied Europe. SS personnel forced deportees onto the ramp, shouted instructions, and split families in moments. SS doctors stood at the center of this process. Their “assessment” determined who would be exploited for labor and who would be killed immediately.

Selection was not medical care in any humane sense. It was an administrative act that gave murder a clinical mask. People deemed “unfit” for labor—often children, the elderly, the ill, and many mothers with small children—were typically sent directly to gas chambers. Those deemed “fit” were registered, stripped, tattooed, and worked under conditions designed to break bodies. In this system, a doctor’s hand could function as a death sentence.

Many SS doctors found selections unpleasant and tried to limit their exposure. Mengele became infamous because he did the opposite. Survivors described him arriving on the ramp even when not scheduled, carefully groomed, confident, sometimes smiling, sometimes performing calmness as if it were a private signal of power. The outward image mattered to him: the cultured professional who could decide human futures as if sorting paperwork.

Mengele also carried out selections inside the camp. He inspected barracks and infirmaries and could order prisoners who did not recover within a set period to be killed. Within Auschwitz, the power to select was the power to kill. The camp turned physicians into gatekeepers of life and death, using the appearance of “health” as a criterion for survival under slavery.

At the same time, Mengele used Auschwitz as a laboratory. The camp placed thousands of people under total SS control, enabling experiments that would have been impossible under ethical or legal constraints. His projects were tied to Nazi racial ideology and to his own ambition: studies of twins, of people with dwarfism, and of traits such as heterochromia, or different-colored irises.

His obsession with twins was rooted in a warped approach to genetics. Identical twins, he believed, could serve as perfect “control” and “test” pairs. Twins also represented a fantasy within Nazi thinking: the possibility of manipulating reproduction to increase the birth of “desired” populations. When transports arrived, Mengele searched the crowds for twins. A question that could terrify parents—“Are you twins?”—might pull children from the line and temporarily spare them immediate death.

That apparent “reprieve” carried its own horror. Twin children were subjected to constant examinations and measurements. Blood was drawn repeatedly. Physical features were cataloged in obsessive detail. Medical procedures were performed without consent, and in many accounts, without adequate anesthesia or concern for suffering. The children were treated as specimens. Their pain was ignored as irrelevant to the “research.” In the logic of the camp, harm could be described as data collection.

Other prisoners were chosen because they matched a category that interested the doctor. People with dwarfism were examined and subjected to experimental procedures. Prisoners with unusual eyes were targeted. In some cases, chemicals were injected into eyes in attempts to affect color, causing injury and long-term damage. The goal was never to heal. It was to control bodies for ideological questions that had no legitimate scientific foundation.

Mengele’s work in the Roma family camp included attention to noma, a gangrenous disease associated with severe malnutrition and poor hygiene—conditions created by imprisonment itself. Instead of addressing the conditions that produced such illness, SS “research” treated disease as an opportunity. Suffering was not a problem to solve but a resource to mine. The camp inverted the ethics of medicine: it manufactured misery and then treated misery as a laboratory asset.

Mengele’s projects did not stay contained within the barbed wire in his imagination. He presented his work as if it belonged to legitimate science. He kept meticulous notes, filled out detailed questionnaires, and treated the camp’s records as if they were medical charts rather than instruments of terror. He corresponded with researchers and institutions inside Germany, seeking professional recognition and treating Auschwitz as a “research opportunity” rather than a crime scene. In that mindset, the moral inversion was complete: the “crime,” he suggested in conversation, would be failing to exploit what the camp made possible.

This posture—bureaucratic, orderly, educated—was part of what survivors found so disturbing. Mengele was not remembered as a shouting fanatic who lost control. He was remembered as controlled. Some survivors recalled him speaking softly to children before sending them away. Others recalled the contrast between his calm manner and the brutality that followed. In social settings with fellow SS personnel, he could be charming and witty. In the camp, he could be cold, methodical, and indifferent to suffering because he had trained himself to treat pain as irrelevant.

Auschwitz included the Roma family camp, where SS policies produced starvation, disease, and death. Mengele exploited that population for pseudo-scientific study, treating deprivation and illness as “material” rather than suffering to relieve.

One reason Mengele’s name endures is that he specialized in choices that felt personally targeted. Selection already meant losing family in minutes. Mengele intensified that terror by searching for twins and by transforming the selection line into a hunting ground. For a parent, the moment could be unbearable: admitting “yes” might spare the children immediate death but condemn them to a laboratory; denying it might send them to the gas chambers. Either way, the SS had the power. Mengele’s question turned family bonds into a trap.

The end of the Auschwitz period did not bring immediate clarity for justice. In 1945, Europe was a landscape of ruins and displaced people. Millions were moving: liberated prisoners, refugees, demobilized soldiers, and perpetrators trying to blend into the crowd. Allied intelligence agencies were focused on stabilizing occupied zones and preparing for new geopolitical conflict. Identification lists were incomplete. Documents were missing or forged. In that chaos, Mengele could become one more anonymous German man with a paper trail that did not quite match the truth.

His escape to Argentina in 1949 was not a solitary feat of endurance. It was enabled by networks of assistance, sometimes ideological, sometimes opportunistic. Former SS men helped each other. Sympathetic officials looked away. Money traveled from Germany to South America. The broader phenomenon—often discussed under the label “ratlines”—included clergy, smugglers, and intermediaries who moved people across borders in the postwar years. Humanitarian travel documents, meant to address a refugee crisis, were among the tools that perpetrators could misuse.

For years in Buenos Aires and beyond, Mengele lived a life that was ordinary on the surface: work, social gatherings in expatriate circles, routines. A man associated with the murder and torture of children could eat dinner, meet friends, and watch life continue. When pressure increased—after high-profile Nazi prosecutions and after Israel captured Adolf Eichmann in 1960—Mengele moved more cautiously, retreating into rural areas and relying on contacts. Each move was an admission that law could reach him, but not quickly enough.

The pursuit of Mengele involved multiple governments, and it exposed the limits of international justice. Declassified investigations, including later reports by U.S. authorities examining efforts to locate him, show how difficult it could be to follow a suspect across borders when he had allies, aliases, and time. Even credible leads could collapse for lack of cooperation or for lack of resources. Some states were reluctant to confront communities that sheltered fugitives. Some agencies pursued other priorities. The result was a manhunt that became famous, yet often ineffective.

When his death was confirmed in the mid-1980s, the news did not bring closure so much as a new kind of anger. Mengele had died by accident, not by judgment. He had not sat in a courtroom to face witnesses. There was no verdict that matched the scale of the crimes. For many survivors, the confirmation felt like a final theft: even accountability had been denied. The act of exhumation and identification proved his escape, but it also proved that time, not law, had ended his flight.

The legacy of Mengele’s crimes is therefore twofold. It is a warning about medicine without ethics and science without humanity. But it is also a warning about justice without persistence. The Nuremberg Code arose from the determination to state, in legal form, what should have been obvious: that consent is essential and that human beings are not raw material for experiments. Yet the most famous “doctor” of Auschwitz escaped the courtroom that produced those principles. The contradiction remains part of the story the world must remember.

The horror of Mengele’s story cannot be separated from the system around him. Auschwitz-Birkenau was not a rogue experiment run by a single man. It was an institution built for mass murder and exploitation, staffed by administrators, guards, engineers, and medical personnel who enabled it. Mengele became a symbol because his role was visible—because he appeared on the ramp, because he singled out children, because survivors could attach a face to the experience of selection and “experimentation.” But the institution that enabled him was vast, and its violence was systemic.

This distinction matters because it prevents a comforting myth: that one extraordinary monster caused the worst outcomes, and that removing one man would have restored sanity. The camp would still have killed without Mengele. Yet his particular crimes demonstrate how quickly professional ambition can fuse with state ideology when the victims are declared less than human.

As the war turned against Germany, Mengele’s presence at Auschwitz ended as abruptly as it began. In January 1945, with the Soviet army approaching, the SS evacuated Auschwitz and destroyed evidence where it could. Prisoners were forced on death marches. Camp staff fled west. Mengele left with retreating forces, attempting to preserve parts of his records and belongings, and began a long flight from accountability.

In the postwar chaos, Allied forces detained vast numbers of German soldiers and SS personnel. Mengele was captured by American troops and held in prisoner-of-war camps. Yet he was released, not recognized as the wanted doctor of Auschwitz. Identification systems were imperfect, records were incomplete, and the scale of detentions overwhelmed administrators. One factor later noted by historians was that he did not bear the SS blood group tattoo that helped identify many SS members. Without that marker, he could claim a different identity and walk away.

For years he hid in Germany under false names, working as a farm laborer. Then, in 1949, he fled Europe to Argentina, traveling along escape networks sometimes called “ratlines.” He used a travel document issued through postwar humanitarian systems of documentation. The aftermath of the war created enormous movements of displaced persons, refugees, and survivors. In that turbulent world, some perpetrators exploited the same channels meant to aid the vulnerable.

In South America, Mengele lived with varying degrees of openness, helped by sympathizers and by financial support from his family. Over time, pressure increased. West Germany issued warrants. Israeli intelligence and Nazi hunters pursued leads. Mengele moved between Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil, using aliases and relying on networks that helped former Nazis resettle. He remained a ghost not because he was invisible, but because protection and indifference could be stronger than pursuit.

The hunt for Mengele became one of the most notorious manhunts of the postwar period. Nazi hunters such as Simon Wiesenthal publicized his crimes and pressed governments to act. Investigators followed rumors, traced acquaintances, and tried to map the support systems that allowed fugitives to survive. Yet for decades, Mengele remained free. Leads appeared and vanished. Sightings turned out to be mistaken. International cooperation often arrived late, or not at all.

In 1979, Mengele died after suffering a stroke while swimming off the coast near Bertioga, Brazil, and he drowned. He was buried under a false name. For years, authorities did not know he was dead, and the pursuit continued. Only in 1985 were his remains exhumed and his identity confirmed through forensic analysis. Later scientific testing reinforced the identification. He had escaped trial and punishment and died far from the ramp where he once decided life and death.

The fact that he was never tried is not only a story about one man. It is also a story about the limits of postwar justice: displaced Europe, uneven international cooperation, political priorities reshaped by the Cold War, and bureaucracies struggling to process the scale of crimes. Mengele fell through cracks that were created by institutions, not by fate.

Yet the moral reckoning that followed the war did not ignore the medical crimes. The Doctors’ Trial at Nuremberg, held in 1946–47, prosecuted German physicians and officials for crimes including medical experimentation on prisoners. Out of that legal process came the Nuremberg Code, a landmark set of principles emphasizing voluntary consent and ethical constraints in human experimentation. It was drafted in direct response to the Nazi example: a reminder that scientific capability without ethics can become a weapon.

The Nuremberg Code did not end unethical research forever, but it established a foundation for modern medical ethics. Its core insistence—that human beings are not instruments for a researcher’s ambition—stands in direct opposition to what Auschwitz made possible. The Holocaust forced the world to confront a devastating truth: technical skill and education are not safeguards if ideology removes empathy and law removes restraint.

Survivors have carried the heaviest burden of this history. Many twin survivors described lifelong trauma, physical injury, grief for siblings murdered after being used as “controls,” and the peculiar burden of surviving a system designed to erase them. Their testimonies turned an SS doctor’s paperwork into a human story of pain and endurance. They kept the crimes from fading into abstraction and reminded the world that behind every statistic was a child with a name, a family, and a stolen future.

It is tempting to imagine Mengele as an exceptional monster who appeared from nowhere. But his story is also about ordinary structures—universities, research institutes, professional hierarchies—being captured by a regime that defined entire populations as unworthy of rights. Nazi ideology provided justification. Career ambition provided incentive. Auschwitz provided opportunity. The combination produced a physician who transformed the symbols of healing into instruments of cruelty.

The railway ramp at Birkenau is now a historical site. Photographs show tracks disappearing into open ground, and visitors stand where victims once stepped down from freight cars into confusion and terror. The physical space is quiet. The moral space is not. It asks how a society allowed medicine to become a partner in mass murder, and how professionals convinced themselves that brutality could be called “research.”

The lesson is not that evil always looks dramatic. Sometimes it arrives with good manners, polished shoes, and careful paperwork. That is why Mengele remains a warning. Remembering him is not about granting a perpetrator macabre fame. It is about refusing the comfort of distance and insisting on accuracy, accountability, and ethical vigilance.

Justice did not reach Josef Mengele in a courtroom. But history continues to judge him through survivor testimony, archival documentation, and the ethical frameworks built in the aftermath. The responsibility now belongs to the living: to keep the record clear, to resist the misuse of science, and to treat every human being as more than a category on someone else’s clipboard.