The Garbage Gun: They laughed at his cheap, mail-order rifle, until he used it to silence 11 snipers in 4 days. NU

The Garbage Gun: They laughed at his cheap, mail-order rifle, until he used it to silence 11 snipers in 4 days

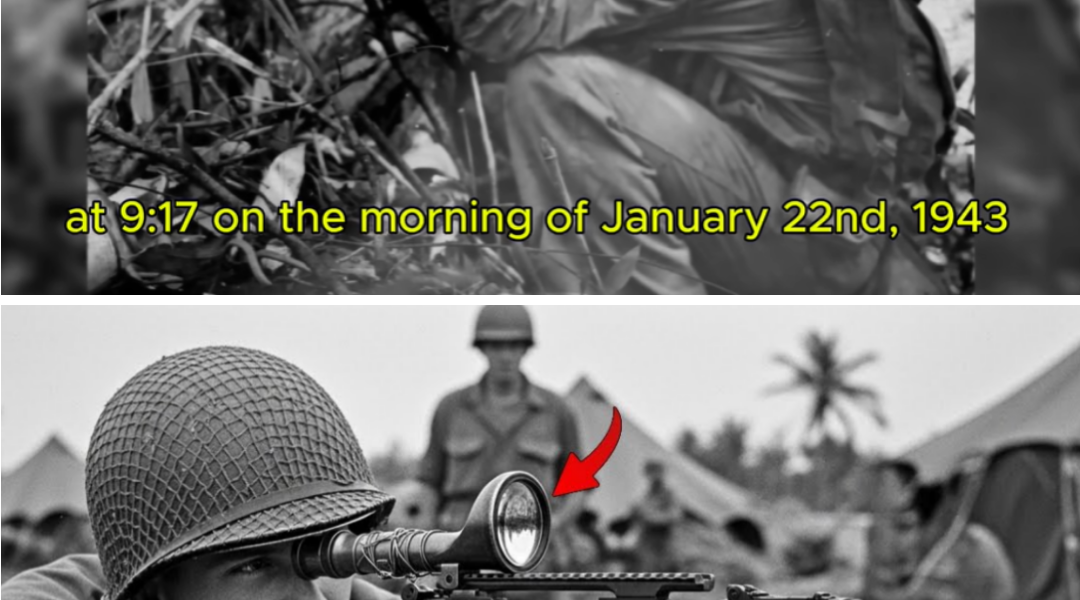

The humid, salt-thickened air of Guadalcanal in January 1943 was a soup of black mold and stagnant rot. Deep within the banyan groves west of Point Cruz, the men of the 132nd Infantry Regiment were being picked apart by a ghost. Fourteen Americans had fallen in seventy-two hours, each killed by a single shot from an invisible enemy. The Japanese snipers, tied into the high canopies of 90-foot trees, were winning.

In the mud of a frontline bunker, 27-year-old Second Lieutenant John George crouched with a weapon that had been the joke of the battalion for six weeks. While his peers carried the rugged, semi-automatic M1 Garand, George held a Winchester Model 70—a bolt-action civilian hunting rifle he had ordered through the mail from Illinois.

THE “TOY” THAT SAVED A BATTALION

John George was no ordinary soldier. In 1939, at just 23, he had become the youngest Illinois State Champion marksman in history, hitting targets at 1,000 yards with clinical precision. When his National Guard unit was called to duty, George knew the standard-issue sights wouldn’t be enough for the dappled light of a jungle canopy. He spent two years of his pay to buy the Winchester, outfitted with a Lyman Alaskan scope.

His commanding officer, Captain Morris, had openly mocked the weapon. “Is that for deer or Germans, George?” he’d asked. “Leave the toy in your tent and carry a real man’s gun.”

But on the night of January 21st, after three more men died from tree-top fire, the mockery stopped. The battalion commander summoned George. “They’re killing us faster than malaria,” the Colonel said. “I want to know if that mail-order sweetheart of yours can actually hit anything.”

THE FOUR-DAY PURGE

At dawn on January 22nd, George began his hunt. He moved alone, refusing a spotter or radioman. He knew that in a sniper duel, two silhouettes were twice as easy to kill as one.

He glassed the massive banyan trees through his 2.5x magnification scope. The jungle was a chaos of movement, but George was looking for something specific: a shift in the shadows that didn’t match the wind. At 9:17 AM, he saw it. A branch 87 feet up shifted unnaturally. Through the glass, he saw the dark shape of a Japanese sniper facing east, waiting for an American supply column.

George adjusted his scope—two clicks right for wind—and squeezed the 3.5-pound trigger. The Winchester barked. 240 yards away, the sniper tumbled through the branches like a broken doll.

The Scorecard of Point Cruz (January 22–25, 1943):

THE BAIT AND THE HOOK

The most dangerous moment came on the third day. George spotted a Japanese sniper low in a palm tree—a mere 40 feet up. It was an amateur position. George hesitated. He had killed eight men; the survivors wouldn’t be this careless.

He lowered his rifle and glassed the surrounding area. Eleven minutes of agonizing patience later, he found the truth. Ninety feet up in a neighboring banyan sat the real threat—an elite marksman watching the palm tree, waiting for George to reveal his position by taking the easy shot.

George used the bait against them. He fired a “snap shot” at the decoy, and as the real sniper turned toward the sound, George worked the bolt and sent a second round into the banyan tree before the enemy could even level his rifle.

FROM HUNTER TO TEACHER

By January 25th, the groves were silent. The threat that had paralyzed an entire battalion had been systematically dismantled by one man and a “mail-order toy.”

Recognizing his genius, the regimental commander, Colonel Ferry, didn’t punish George for his non-standard gear. Instead, he promoted him and gave him a new mission: Create a sniper section. George was given fourteen Springfield rifles with Unertl scopes—leftovers from the Marines—and forty of the best marksmen in the regiment.

George taught them the “Craftsman’s Approach” to war. “The jungle isn’t a battlefield,” he told them. “It’s a hunting ground. You don’t fire to suppress; you fire to execute.” In just twelve days, George’s team confirmed 74 more kills with zero American casualties.

THE MARAUDER’S PATH

John George’s war didn’t end on Guadalcanal. He volunteered for a classified mission in Burma, joining the legendary Merrill’s Marauders. He carried his Winchester over 700 miles of the most “impassable” terrain on earth, crossing mountains and rivers to capture the Myitkyina airfield.

Though the close-quarters nature of the Burma jungle meant fewer long-range shots, George’s reputation preceded him. He was the “Ghost of the 132nd,” the man who proved that skill and the right tool could defy the industrial scale of modern warfare.

LEGACY: “SHOTS FIRED IN ANGER”

After the war, John George became a distinguished academic and a consultant for the State Department on African Affairs. But he never forgot the lessons of Point Cruz. In 1947, he published Shots Fired in Anger, a clinical, unembellished account of small-arms combat. It remains a foundational text for military historians and marksmen today.

John George passed away in 2009 at the age of 90. His Winchester Model 70—the rifle that was laughed at by armorers and captains alike—now sits in the National Firearms Museum in Virginia. It looks like a simple hunting rifle, but it is a $High-Alert$ reminder: The man behind the trigger matters infinitely more than the army behind the man.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.