What American Soldiers Did to SS Guards When They Found Dachau

On the morning of April 29, 1945, the war in Europe was already collapsing. Nazi Germany was dying on its feet. To the men of the 45th Infantry Division, advancing toward a large complex near Munich felt routine—another objective, another set of orders, another long day in uniform.

They thought it was a factory.

They were wrong.

What they found at Dachau concentration camp would not only scar them for life—it would push some of them past the breaking point, into a moment so violent and morally explosive that the U.S. Army would later try to bury it forever.

This is the story of the day the liberators lost control.

THE TRAIN THAT BROKE THE WAR

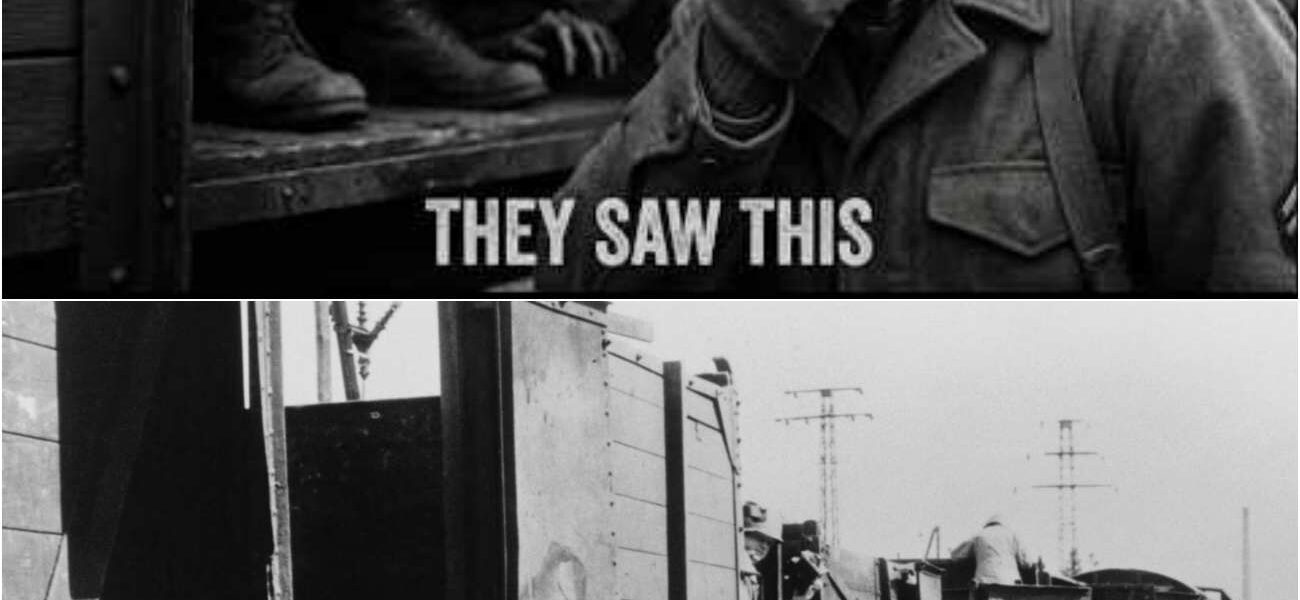

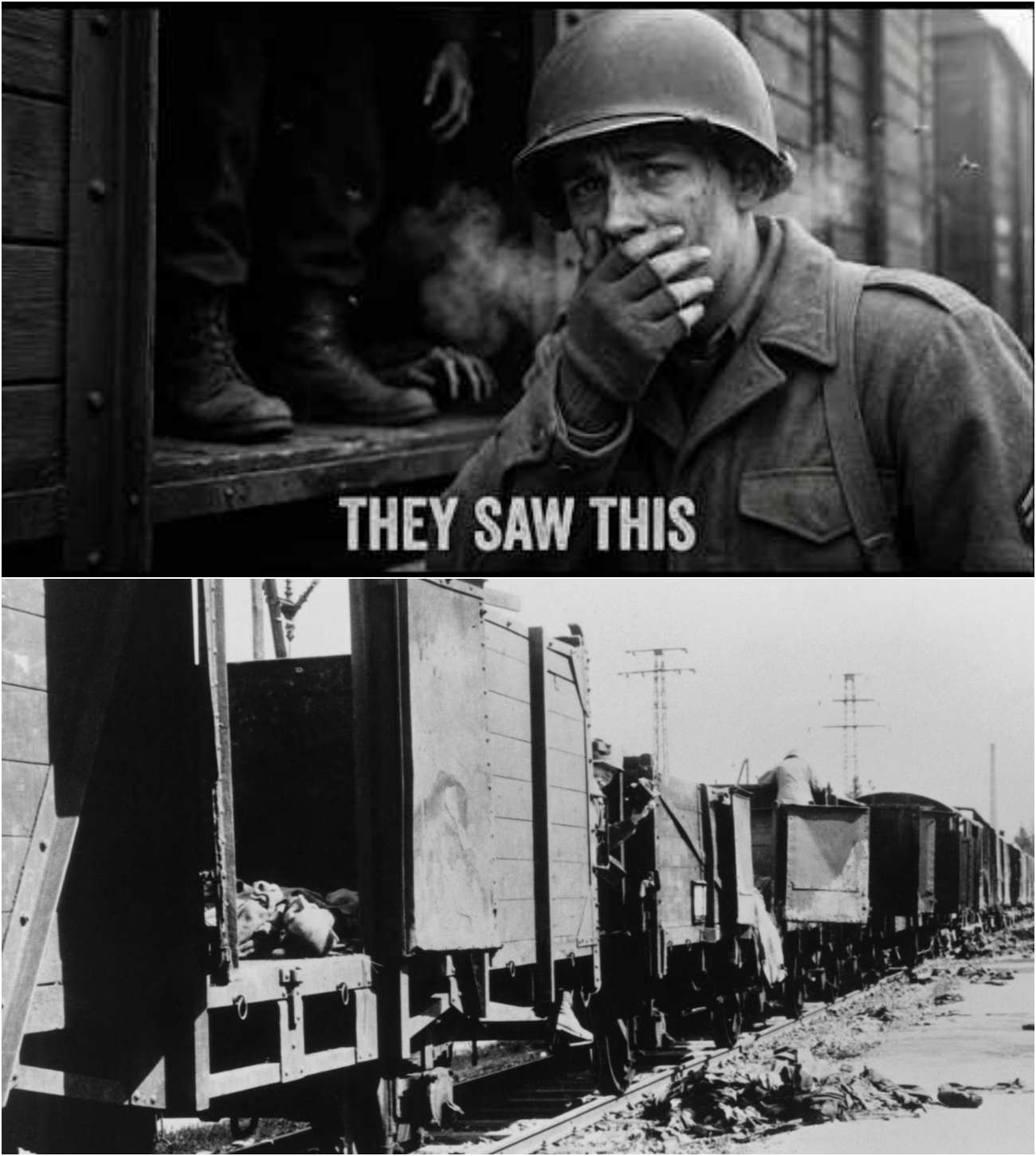

The first thing they reached wasn’t the camp itself, but a railroad siding. Thirty-nine cattle cars sat motionless on the tracks. The smell hit before anything else—sweet, rotten, unbearable.

A lieutenant climbed up and slid open a door.

Inside were bodies. Thousands of them.

Men, women, children—stacked like firewood. Starved. Frozen. Some bore bite marks. The living had tried to eat the dead.

Veteran soldiers dropped to their knees. A 19-year-old from Oklahoma sobbed openly in the snow. Others vomited. These were men who had survived Anzio and Southern France, who had watched friends die under artillery fire—but nothing prepared them for this.

In that moment, grief curdled into rage.

“DON’T LOOK”—AND THEN LOOKING ANYWAY

Lieutenant Colonel Felix Sparks tried to keep order. “Keep moving,” he shouted. “Don’t look.”

No one could obey.

The soldiers passed the train, eyes locked with hollow skulls that seemed to stare back. More than 2,000 bodies lay there—evidence of systematic murder delivered to them without warning.

From that instant, the rules changed.

The Geneva Convention felt meaningless. Surrender protocols felt obscene. The war stopped being abstract and became personal.

THE CLEAN NAZI AND THE WHITE FLAG

At the camp gate, chaos erupted.

Inside the fences, nearly 30,000 prisoners—skeletal, barefoot, barely alive—screamed with joy as American troops entered. They cried “Americans! Americans!” and surged forward like ghosts learning they were free.

Outside, the SS still stood.

The camp commandant had fled, but a young SS officer remained, impeccably dressed. He stepped forward under a white flag and announced he was surrendering Dachau to the United States Army.

He expected professionalism.

He expected the rules.

An American officer looked at him—then back at the train.

The officer spat in his face.

THE COAL YARD

Near a coal yard, a group of SS guards tried to surrender. Hands up. “Hitler kaput,” they shouted, believing the phrase might save them.

It didn’t.

Lieutenant Jack Bushyhead, a Native American officer, had just seen the crematorium. Ash still warm. Ovens full. His hands were shaking.

He didn’t shout an order.

He gestured.

The SS men were lined up against a wall. Fifty of them. Some cried out about the Geneva Convention. A machine gun was mounted. The lieutenant nodded.

Ten seconds later, it was over.

Bodies fell into the coal dust. Blood stained the snow black and red. Some guards twitched on the ground as bullets tore through them again.

When Colonel Sparks arrived and fired his pistol into the air, screaming for the shooting to stop, the gunner looked at him—crying, unrepentant.

“They deserved it,” he said.

EXECUTIONS IN THE TOWERS

The killings didn’t stop there.

At one watchtower, SS guards tried to climb down with their hands raised. American soldiers shot them off the ladder. Their bodies fell into the moat.

The soldiers emptied their magazines into the water to make sure.

One GI later wrote home:

“It wasn’t war. It was an execution. And I didn’t feel a thing.”

WHEN THE VICTIMS TOOK THEIR TURN

Then the prisoners joined in.

Barely able to stand, they dragged an SS guard from a tower and beat him to death with shovels, sticks, and fists. American soldiers stood nearby, smoking.

“Should we stop them?” an officer asked.

“No,” a sergeant replied. “Let them finish.”

In another section of the camp, prisoners found a German kapo—a collaborator who had beaten fellow inmates for the Nazis. They drowned him in a latrine.

For roughly an hour, Dachau had no law.

THE INVESTIGATION NO ONE WANTED

Photos were taken. American soldiers posing beside executed SS guards. Images from the coal yard.

An official investigation followed. The report concluded U.S. troops had violated international law. Court-martials were recommended.

The file landed on the desk of George S. Patton.

Patton studied the photos—first the SS dead, then the train.

He exploded.

“War crimes?” he reportedly said. “You walk into a place like that and expect my boys to follow the rule book?”

Patton called the SS “the slime of the earth.” He refused to sign the charges. The report was destroyed—or buried so deep it might as well have been.

Dwight D. Eisenhower agreed. Prosecuting the men who liberated Dachau would shatter morale. The investigation was quashed.

No trials. No punishments.

HISTORY’S MOST UNCOMFORTABLE QUESTION

Today, Dachau stands as a memorial to its victims. There is no monument for the SS guards executed against the wall.

Neo-Nazis point to the reprisals and say, “See? The Americans were just as bad.”

Historians reject that lie.

This was not policy.

This was not genocide.

This was a human breaking point.

The soldiers of the 45th Infantry Division didn’t come to Dachau to kill prisoners. They came to end a war—and walked into hell.

One veteran said years later:

“I know killing prisoners is wrong. But that day, in that place, it felt like the only right thing to do.”

That is the question Dachau leaves behind.

When you see pure evil up close—when it stares at you from a boxcar—do you remain a soldier… or do you become an avenger?

History still hasn’t answered.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.