8 sailors, one rubber boat, and a daring explosion—the only ground attack on Japan’s mainland in history. NU

8 sailors, one rubber boat, and a daring explosion—the only ground attack on Japan’s mainland in history

At 11:58 p.m. on July 23, 1945, the sea off the coast of Karafuto was as black and cold as ink. Commander Eugene Fluckey, the 31-year-old captain of the USS Barb, stood in the conning tower, his binoculars fixed on two tiny rubber boats bobbing toward the Japanese shoreline.

Fluckey was already a legend. He held the Medal of Honor for a daring raid into a shallow Chinese harbor months earlier. He had destroyed 17 ships and recently led the first-ever submarine-launched rocket attacks in naval history. But tonight, his target wasn’t a ship. It was a 16-car freight train.

The Japanese had moved 400 trains along this coastal railway in the past month, funneling ammunition and troops south to brace for an American invasion. Fluckey had watched them through his periscope for weeks, frustrated that his torpedoes couldn’t reach the land. Finally, he decided: if the submarine couldn’t sink the train, his sailors would.

The Scouting Party: Eight Boy Scouts and a Pickle Jar

This was a mission without precedent. No American combat troops had ever landed on the Japanese home islands during the war. To pull it off, Fluckey called for volunteers with two bizarre requirements: they had to be unmarried, and they had to be former Boy Scouts. He believed the scouts had the innate navigation and discipline needed to survive a night in enemy territory.

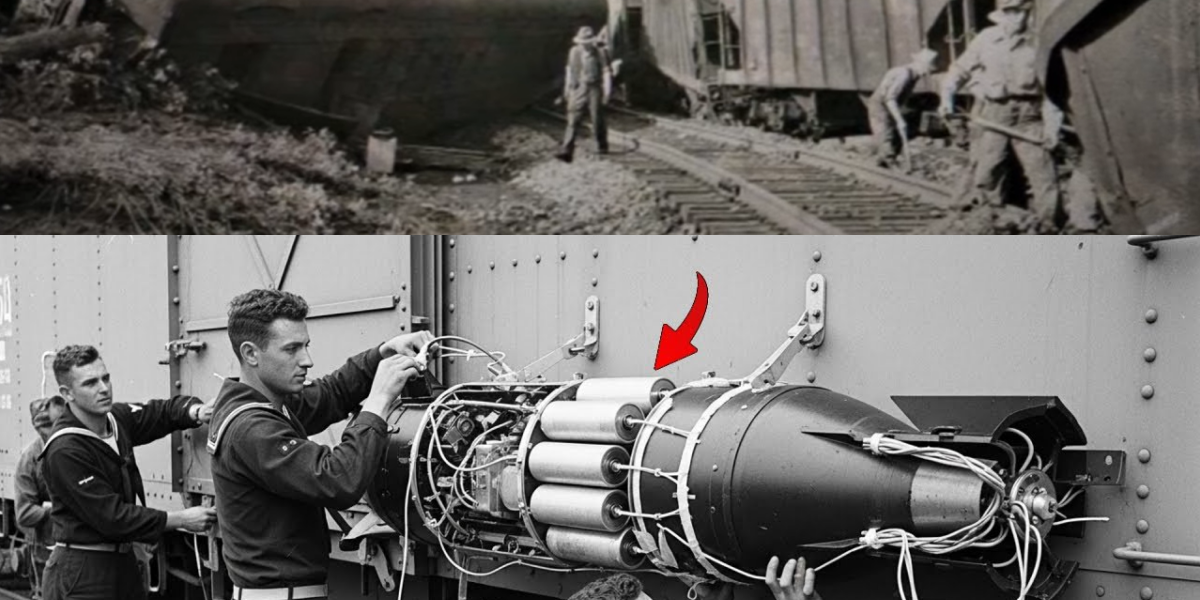

The “invasion force” consisted of eight men, led by Lieutenant William Walker. They carried a 55-pound scuttling charge—an explosive usually reserved for destroying the submarine itself.

The detonator was a masterpiece of improvisation. Electrician’s Mate Billy Hatfield had rigged a micro-switch inside a pickle jar. He remembered a childhood trick of placing walnuts on tracks to watch trains crack them open. He designed the switch so that when a heavy locomotive passed over the rail, the track would sag just enough to compress the switch and complete the circuit. Simple physics, catastrophic potential.

40 Minutes in the Lion’s Den

At 12:07 a.m., the boats hit the gravel. The eight men dragged their rafts into the pine trees and moved in single file. They had 90 minutes before the first hint of dawn would expose them.

The terrain was a nightmare. Between the beach and the railway lay a 6-foot drainage ditch filled with icy water and 1,500 feet of flat, open ground. If a Japanese patrol spotted them, they were dead; there was nowhere to hide but the tall grass.

They reached the tracks at 12:28 a.m. While six men formed a perimeter, Hatfield and another sailor began to dig. They worked with frantic, silent efficiency. Gravel flew. Sweat stung their eyes despite the biting night air. They buried the bomb between the wooden ties and meticulously positioned the pickle-jar switch flush against the underside of the rail.

By 12:41 a.m., the trap was set.

They spent the next few minutes erasing their footprints, smoothing the gravel until the tracks looked undisturbed. If a Japanese maintenance crew inspected the line at dawn, they would see nothing.

The Escape and the Wait

The return trip was a blur of adrenaline and mounting dread. Every shadow looked like a Japanese sentry. Every snap of a twig sounded like a rifle bolt. They crossed the open ground in three minutes, waded through the ditch, and reached the rubber boats just as the eastern horizon began to turn from black to a ghostly gray.

They paddled hard, fighting the incoming tide. By 1:18 a.m., they reached the Barb. Hands reached down from the deck to pull them aboard. The boats were deflated, the hatch was sealed, and Fluckey took the submarine to periscope depth.

“Now,” Fluckey whispered to his crew. “We wait.”

For over an hour, the control room was silent. The only sound was the hum of electric motors and the occasional ping of the sonar. 2:00 a.m. passed. 2:30 a.m. Fluckey was about to order a withdrawal when the radar operator spoke up: “Surface contact on land, Captain. Moving south. Speed 30.”

The Fireball at 2:47 A.M.

Fluckey pressed his eye to the periscope. He saw the silhouette of the locomotive, its headlight cutting through the mist, smoke trailing from the stack. It was a heavy supply train, exactly what they had hoped for.

As the train reached the section of track where Hatfield had buried the device, Fluckey held his breath.

At 2:47 a.m., the coastline erupted.

A pillar of fire shot 200 feet into the air. The 55-pound charge had detonated precisely as the locomotive hit the switch, triggering the engine’s massive boiler to explode. Superheated steam and burning coal rained down on the wreckage.

The front of the train vanished in the blast. The momentum of the rear cars drove them into the fireball, accordion-folding into a mountain of twisted steel. Because the train was carrying ammunition, secondary explosions rippled through the valley for minutes. Eight seconds after the flash, the deep, rumbling boom vibrated the Barb’s hull, 950 yards offshore.

“Take her down!” Fluckey ordered. The Barb slipped beneath the waves and headed for deep water just as Japanese coastal defenses began to scramble.

The Legacy of the Locomotive

When the USS Barb returned to Midway, a small crowd was waiting. Word had already spread. The “Midnight Raiders” were exhausted, but they had rewritten the rules of naval engagement.

The Japanese never realized the explosion was an American sabotage mission. Their internal communications blamed a “catastrophic boiler failure” and poor maintenance. They spent weeks clearing the wreckage, unknowingly allowing American intelligence to map their supply disruptions.

The USS Barb finished the war as one of the most decorated vessels in the fleet. But the most famous part of her legacy is her battle flag. Among the rows of white blocks representing sunken ships, there is one unique silhouette that appears on no other submarine flag in history: A black steam locomotive.

Commander Eugene Fluckey lived to be 93, always insisting that his greatest achievement wasn’t the Medal of Honor, but the fact that in five war patrols, he never lost a single man. He proved that with a little ingenuity, a few Boy Scouts, and a pickle jar, even a submarine could conquer the land.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.