Engineers Called His B-25 Gunship “Impossible” — Until It Sank 12 Japanese Ships in 3 Days. VD

Engineers Called His B-25 Gunship “Impossible” — Until It Sank 12 Japanese Ships in 3 Days

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17, 1942, Captain Paul I. Gunn crouched beneath the wing of a battered Douglas A-20 Havoc at Eagle Farm Airfield near Brisbane. Sparks leapt from welding torches as mechanics cut and reinforced the aircraft’s nose, tearing out the bombardier’s position and replacing it with something no bomber was ever meant to carry—four heavy .50-caliber machine guns aimed straight ahead.

Gunn watched in silence.

He was forty-three years old, a career naval aviator who had already lived several lifetimes before the war reached the Pacific. He had flown boats, fighters, and transports. He had built an airline in the Philippines. And now, while he stood under that wing, his wife and four children were prisoners of the Japanese in Manila, held behind barbed wire in the Santo Tomas internment camp.

Every mission mattered.

Every mistake cost lives.

The Fifth Air Force was bleeding.

Japanese convoys moved supplies and troops into New Guinea almost at will. High-altitude bombing didn’t work. Bombardiers couldn’t hit moving ships, and when the bombers flew lower, Japanese deck gunners cut them apart. In July alone, Gunn had watched eleven A-20s fail to return.

The math was simple and brutal.

If nothing changed, the Allies would lose New Guinea.

Paul Gunn believed bombers were being used the wrong way.

He believed they should fight like fighters.

His idea was dangerous, untested, and dismissed by most engineers as reckless. Bombers would come in low—so low the pilots could see faces on enemy decks. They would suppress anti-aircraft fire with overwhelming forward gunpower, then drop bombs that skipped across the sea like stones, slamming into hulls below the waterline.

But first, the aircraft had to survive the approach.

That meant guns.

Bigger guns.

The A-20 Havoc’s existing .30-caliber machine guns were useless against ships. Gunn stripped .50-caliber weapons from wrecked fighters, mounted them into the bomber’s nose, and shifted equipment aft to keep the aircraft from diving uncontrollably.

The first test flight nearly killed the pilot.

The second one flew—barely.

That was enough.

On September 12, 1942, sixteen modified A-20s screamed in at treetop height over the Japanese airfield at Buna. Their guns hammered nonstop, shredding aircraft on the ground and silencing defenses before anyone could react.

Fourteen Japanese planes destroyed.

Zero Allied losses.

General George C. Kenney wanted more.

But Gunn knew the A-20 wasn’t enough.

He needed a bigger hammer.

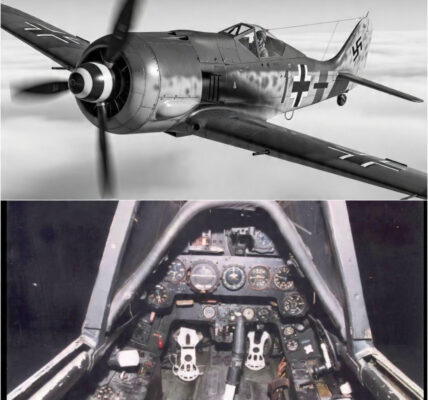

He chose the B-25 Mitchell.

Longer range. Heavier structure. Room for more guns.

He removed the bombardier entirely and filled the nose with four .50-caliber machine guns. Then he added external cheek mounts. Then he rotated the top turret forward.

Fourteen forward-firing guns.

The ground crews laughed and called it “Pappy’s Folly.”

Gunn flew it anyway.

The aircraft wanted to fall out of the sky on takeoff, but once airborne, it was unstoppable.

Kenney ordered mass conversion immediately.

Engineers back in the United States protested. They said it couldn’t fly. Said it was unsafe. Said it violated every design principle.

Kenney silenced them with one sentence.

“Twelve of those airplanes just destroyed an entire Japanese convoy.”

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea began on March 3, 1943.

Eight Japanese transports and eight destroyers carried nearly 7,000 troops toward New Guinea. High-altitude bombers failed again, as expected. Then, at mast-head height, the Strafers arrived.

They came in line abreast, a wall of fire.

Fourteen guns per aircraft.

Deck crews died where they stood. Bridges shattered. Engines burned. Bombs skipped off the water and detonated inside hulls.

Ships sank in minutes.

By nightfall, the convoy was gone.

The Japanese never again attempted large-scale reinforcement by sea.

The war in the Southwest Pacific had turned.

Word spread fast.

Factories retooled. North American Aviation built thousands of Strafer variants directly inspired by Gunn’s field modifications. Some carried a 75-mm cannon in the nose. Others carried rockets, napalm, or parafrag bombs.

They hunted ships.

They hunted aircraft on the ground.

They hunted supply lines until Japan could no longer move safely in daylight—or darkness.

The Japanese gave them a name.

“The Black Death.”

Gunn kept flying.

Not because he had to.

Because his family was still imprisoned.

Every mission brought him closer to Manila.

Then, in November 1944, Japanese bombers struck Tacloban airfield. Gunn was thrown to the ground by the blast. Shrapnel tore into his leg and shoulder. Surgeons told him his flying days were over.

He ignored them.

On February 3, 1945, American forces liberated Santo Tomas.

Gunn flew to Manila the next day against medical orders, leaning on a cane, gray and gaunt from years of strain. His wife didn’t recognize him at first.

Then he spoke her name.

They had survived.

That was the victory he cared about most.

By war’s end, nearly 5,000 B-25 Strafers had been built using Gunn’s concepts.

They sank over 800 ships.

Destroyed 2,000 aircraft on the ground.

And broke the back of Japanese logistics across the Pacific.

Paul Gunn never sought fame. He never chased rank. He wanted results.

Modern gunships, close-air-support aircraft, and attack doctrine trace their lineage directly to his work.

He proved bombers could fight forward.

He proved innovation could save lives.

And he proved that one determined man, armed with tools, courage, and an unshakable reason to fight, could change the course of a war.

Paul Gunn didn’t just build airplanes.

He built a way to win.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.