October 14th, 1967, a 19-year-old private first class named James Torrance steps off a deuce and a half truck. NU

October 14th, 1967, a 19-year-old private first class named James Torrance steps off a deuce and a half truck

October 14th, 1967, a 19-year-old private first class named James Torrance steps off a deuce and a half truck. He has just spent three weeks in the Iron Triangle, sleeping in mud that smelled of rotting vegetation and cordite. He is caked in grime. His fatigues are stiff with dried sweat and his boots are rotting off his feet.

He looks around Long Bin and sees a swimming pool. He sees a basketball court. He sees a post exchange selling Seikko watches and stereo systems. He sees a blindingly strange normality. This is the central paradox of the American war in Vietnam. It was a conflict defined by the primitive terror of the jungle ambush, yet sustained by the most sophisticated, expensive, and massive logistical infrastructure the world had ever seen.

For every soldier pulling a trigger in the bush, there were seven men in the rear, building roads, frying hamburgers, fixing radios, and managing a supply chain that stretched 7,000 m back to San Francisco. You have heard the stories of the firefights. You have seen the footage of the Hueies dropping into hot LZ’s. But to understand the daily reality of the Vietnam War, you must look away from the treeine and look at the base.

From the sprawling city-sized complexes like Long Bin and Daang to the muddy ratinfested firebases cut out of the mountaintops near the Le Oceanian border, the base was the center of gravity for the American soldier. It was where the war stopped and the waiting began. It was where the collision between American industrial abundance and the harsh scarcity of Vietnam was most violent.

By 1969, the United States military had constructed a network of bases that consumed nearly half of the total war budget. They poured millions of tons of concrete into a country that had previously possessed only a few hundred miles of paved road. They built deep water ports, airfields capable of handling B-52s, and barracks that could house half a million men.

But the question remains, how did they actually live in these places? What was the psychological toll of fighting a war where you could eat a hot steak dinner at 18,800 hours and be under mortar fire by midnight? This story is not about the generals who drew the maps. It is about the grunts, the clerks, the mechanics, and the nurses who lived inside the lines.

It is about the smell of burning diesel mixed with burning excrement. It is about the boredom that was more dangerous than the enemy. It is about the frantic effort to recreate home in a place that wanted to kill you. To understand the life of the soldier in Vietnam, you have to understand the geography of their survival. The American military did not just occupy land. They terraformed it.

They attempted to impose a grid of order upon a chaotic insurgency. Zoom out. Look at the map of South Vietnam in 1965. It is a narrow curve of land flanked by the South China Sea to the east and the jagged spine of the Anomite Mountains to the west. The infrastructure is practically non-existent. The French colonial roads are narrow, cratered, and conducive to ambush.

There are no ports capable of offloading the massive tonnage required to sustain a modern mechanized army. General William West Morland knew that to fight a war of attrition, a war based on body counts and overwhelming firepower, he needed a logistics tale that was seemingly infinite. He needed to move men, artillery shells, and ice cream into the interior faster than the Vietkong could disrupt them.

This requirement birthed the greatest construction project in military history. A consortium of American construction firms known as RMKBRJ was hired to literally build the stage for the war. They employed tens of thousands of Vietnamese civilians and imported thousands of skilled laborers from South Korea and the Philippines. Between 1965 and 1967, they dredged harbors at Cameron Bay, turning a quiet, sandy inlet into one of the busiest ports in the world.

They laid asphalt over rice patties. They leveled hilltops. The result was a hierarchy of existence. At the top were the super bases. Places like Long Bin, Daang, Cameron Bay, and Tanute. These were not just camps. They were American cities transplanted into Asia. Long Bin Post covered 25 square miles. It had its own bus system, its own traffic laws, its own water treatment plant, and a population larger than many state capitals.

Here, soldiers lived in wooden hooches with metal roofs, slept on cotss with mattresses, and had access to electricity. The threat of death here came from erratic rocket attacks, usually at night, random and impersonal. But for the most part, life in the super base was a job, a 9-to-ive shift in uniform. Below the super bases were the division base camps.

Places like Coochi for the 25th Infantry Division or Camp Evans for the First Cavalry. These were rougher, closer to the fighting, but still relatively permanent. You had hot food, usually. You had showers, sometimes gravity-fed barrels, sometimes actual plumbing. You had clubs where enlisted men could drink warm beer and listen to Filipino cover bands play the Rolling Stones.

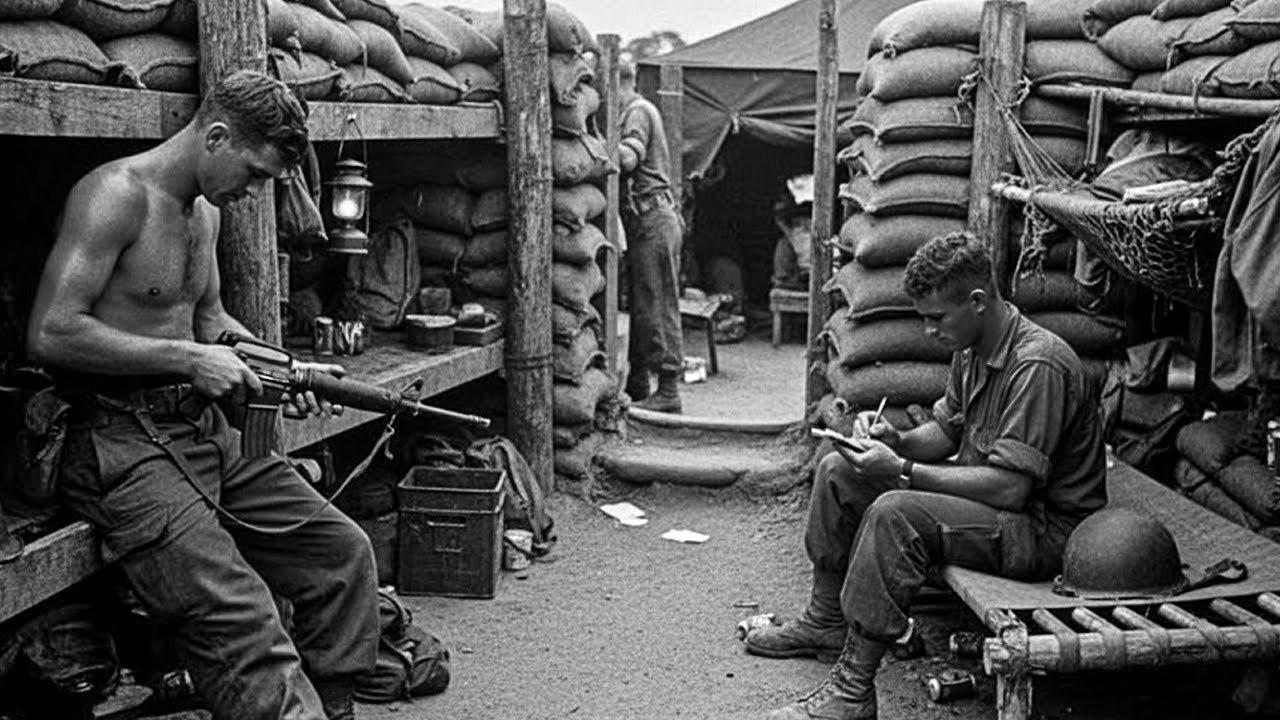

And then at the very edge of the American Reach were the fire support bases, the FSBs. These were temporary scars on the land carved out of the jungle by bulldozers and high explosives. They existed for one purpose, to provide artillery cover for the infantry operating in the field. An FSB might last 6 months or it might last 6 weeks. Life here was trogoditic.

Men lived in bunkers reinforced with sandbags and ammunition crates. There were no showers. Water came in by helicopter and black rubber bivbits. Food was sea rations heated with a pinch of C4 plastic explosive if you were brave or eaten cold if you were tired. The smell here was different. It was the smell of unwashed bodies, wet earth, and fear.

The disparity between these worlds created a unique psychological friction. A soldier could be pulled from the field where he had been sleeping in the rain and watching his skin rot from jungle rot and within 30 minutes be standing on a tarmac at Daang surrounded by men in starched uniforms who smelled like soap. It was a jarring transition that induced a kind of whiplash.

The war was everywhere and yet in the rear it felt like it was nowhere. Let us look at the numbers. In World War II, the ratio of combat troops to support troops was roughly even. By Vietnam, that ratio had shifted dramatically. For every man who actively patrolled the jungle, there were 6 to 10 men, ensuring he had bullets, boots, and letters from home.

This created a massive class divide within the military itself. The grunts, or boon rats, looked with disdain and envy upon the remfs, rear echelon motherfers. The friction between those who lived in the mud and those who lived in the air conditioning was a constant simmering undercurrent of the base life. But even the safest base was an illusion.

The perimeter wire was a psychological boundary as much as a physical one. Inside the wire, you were American. Outside the wire, you were a target. The Vietkong and the North Vietnamese army understood this reliance on the base. They knew they could not defeat the Americans in a head-to-head stand-up fight.

So they turned the bases into prisons. They mined the roads leading in and out. They launched 122 mm rockets into the mess halls at dinnertime. They made sure that even when a soldier was sleeping in a bunk bed, he was never truly safe. The setup of a forward operating base or a fire support base followed a grimly predictable architectural logic.

It began with the violence of creation. Imagine a hilltop in the central highlands. Dense double canopy jungle. Ancient trees. Silence broken only by insects. Then the sky tears open. F4 phantoms drop napalm and high explosive ordinance burning and blasting the vegetation away. Then come the CH47 Chinuks slinging bulldozers underneath their bellies.

The engineers, the CBS or Army combat engineers drop in. They push the scorched earth into BMS. They clear fields of fire. A fire support base was usually circular or triangular. At the center lay the tactical operations center, the TOC. This was the brain, usually a deep bunker buried under layers of sandbags and logs filled with radios, maps, and the constant static chatter of the war.

Around the TOC were the artillery pits, 105 mm or 155mm howitzers, the reason the base existed. These guns could throw shells 10 miles in any direction, providing a protective umbrella for the infantry patrols walking through the valleys below. Surrounding the guns were the living quarters, the hooches or bunkers, and around it all the perimeter, a burm of earth, then a trench, then layers of concertina wire, razor-sharp coils tangled together to snag clothing and skin.

Interspersed in the wire were claymore mines, trip flares, and foo gas drums. Npalm mixed with soap rigged to detonate and spray liquid fire. Life inside this circle was a study in contrasts. It was primitive living supported by space age technology. A soldier on a firebase might not have bathed in 3 weeks, but he could call in an airirst strike from a jet flying at Mach 1.

He might be eating ham and lima beans from a can packed in 1952, but he was listening to the latest Mottown hits on a transistor radio. The daily routine of the base was dictated by the sun and the enemy. Mornings began before dawn. Stand two. Every man on the perimeter moved to his fighting position. Weapon ready, eyes scanning the wire.

The transition from night to day was the most dangerous time. The enemy liked to attack when the shadows were long and the defenders were groggy. If no attack came, the sun rose and the heat began its climb. By 1,000 hours, the base was baking. Work details commenced. Filling sandbags, it is able to overstate the importance of sandbags in the life of a Vietnam soldier.

They were the fundamental building block of survival. Millions of them. Soldiers filled them with red clay, tied them, stacked them, realized the rain had rotted the bottom layer, and filled them again. It was a Cisophian task. A single bunker could require 500 sandbags. A base required tens of thousands.

The burlap rotted in the humidity or the rats chewed through them or the monsoon rains turned the filling to soup. So you filled them again. While the grunts filled sandbags, the logistics machine kicked into gear. The log bird, the supply helicopter, was the umbilical cord. It brought everything. Mail, ammo, water, hot a insulated mermite cans if you were lucky.

The sound of the rotor blades was the sound of life. When the bird landed, the dust storm it kicked up coated everything, stinging eyes and filling mouths with grit. But no one cared. The bird meant connection, but the bird also took things away. It took the body bags, the black green rubberized bags containing the remains of men who had been alive at breakfast.

On a firebase, the proximity of life and death was claustrophobic. You ate your lunch sitting on a crate of 105 mm shells that would kill people 5 miles away in an hour. You slept 10 ft from where a medic was treating a sucking chest wound. There was no sanitizing the war here. Contrast this with the division base camps.

At places like Camp Eagle or Chuai, the architecture was more permanent and the boredom was more insidious. Here, the enemy wasn’t always the NVA. Often, it was the crushing monotony and the deterioration of discipline. In the rear, soldiers lived in hooches. These were wooden structures with screened sides to let air pass through, raised off the ground on cinder blocks to keep out the snakes and the water.

They had plywood floors. Some enterprising soldiers managed to steal or barter for refrigerators, fans, even televisions. They decorated the walls with centerfolds from Playboy and posters of muscle cars. The base camp was a strange ecosystem of commerce and vice. Because the American military flooded the country with dollars and goods, a secondary economy exploded.

House girls, local Vietnamese women, were hired to clean the hooches, shine boots, and do laundry. They were a fixture of life in the rear. They walked through the gates in the morning and left in the evening. This permeability of the base was a constant security nightmare. The woman washing your fatigues might be memorizing the layout of the mortar pits to report back to the Vietkong infrastructure in the local village.

The barber shaving your neck might be a sapper by night. This paranoia permeated every interaction. The friendly wave could be a signal. The smile could be a mask. Food was the great morale regulator. In the base camps, messauls served hot meals. Scrambled eggs, often powdered but hot. bacon, toast, coffee. Dinner might be roast beef or fried chicken.

Ice cream was a strategic obsession. The military shipped millions of gallons of ice cream to Vietnam. It was a symbol of American power that we could keep vanilla dairy frozen in the middle of a tropical war zone. But the distribution was uneven. The rimfs in Long Bin had ice cream machines. The grunts on the fire bases got it only when a compassionate helicopter pilot decided to fly a tub out wrapped in a flack jacket to keep it cold.

Water was another obsession. You sweat gallons a day. Dehydration was a faster killer than the VC. On the fire bases, water was strictly rationed. You didn’t shower. You poured a helmet of water over your head if you had enough. You shaved dry or with cold water. But in the base camps, there were showers. They were often communal concrete slabs with pipes overhead, but the water was wet and it washed off the red dust.

Then there was the waste. A base with 5,000 men produces a staggering amount of waste. There were no sewage treatment plants in the field. There were piss tubes, artillery shell casings buried vertically in the ground, and there were [ __ ] burners. This is the visceral memory that haunts veterans 50 years later.

The latrines were simple wooden structures with cutout barrels underneath. Every day these barrels had to be pulled out, dragged to a clearing, dowsed with diesel fuel, and burned. The smoke was thick, black, and acrid. It clung to your clothes and your skin. It was the defining scent of the base. The setup of the American presence was intended to be overwhelming.

It was designed to prove to the North Vietnamese that resistance was feudal against such material wealth. But the environment fought back. The heat rotted the batteries. The humidity shorted out the radios. The mud swallowed the trucks. And the soldiers caught in the middle adapted. They customized their gear. They built unauthorized bunkers.

They created their own slang, their own rules, their own hierarchies. In the setup phase of this war, we see the illusion of control. The maps in the TOC showed clear lines of control, secure roads, and pacified villages. But the soldier standing guard on the perimeter of FSB Ripcord or pacing the wire at Bian Hoa knew the truth.

The base was an island and the ocean around it was deep, dark, and full of things that were waiting for the sun to go down. The base was also a place of intense noise pollution. It was never quiet. Generators hummed 24 hours a day. Helicopters took off and landed with a rhythmic thumping that vibrated in your chest.

Artillery fire was a constant background percussion, the outgoing that shook the dust from the rafters. You learned to sleep through the outgoing. It was the incoming that woke you up before you even heard it. The subconscious mind of the veteran became tuned to specific frequencies of danger, the whistle of a mortar, the crack of a rocket.

By late 1967, the American footprint was fully established. The logistics tail was wagging the dog. The bases were overflowing with men and material. But the question of how they lived is not just about the physical conditions. It is about the mental state. How do you maintain sanity when you are 19 years old, thousands of miles from home, bored out of your mind one minute and terrified the next? The answer lay in the small rebellions and the desperate camaraderie.

It lay in the cassette tapes sent from home, played until the ribbon snapped. It lay in the illicit pot smoking that became rampant as the war dragged on. It lay in the racial tensions that simmerred in the mess halls and the clubs reflecting the burning cities back in the states. The base was a microcosm of America, but an America under extreme pressure, distorted by heat and violence.

It was a place where the rules of civilization were suspended and replaced by the rules of survival. As we move deeper into the development of this story, we will look at the specific mechanisms of this life. We will examine the knight defensive positions, the sapper attacks that breached the wire, and the drug culture that swept through the barracks.

We will see how the illusion of the safe rear area was shattered during the Tet offensive when the war came crashing through the gates of the super bases. We will zoom in on the specific experiences of the men who kept the machines running and the men who relied on those machines to stay alive.

We have established the stage. The concrete has been poured. The wire has been strung. The stage is set. Now the actors take their places. The sun is going down. The generators are humming. And out in the jungle, something is moving. November 1968. The height of the buildup. The American war machine is consuming supplies at a rate that defies economic logic.

To understand the life of the soldier, you must first understand the sheer crushing weight of the stuff that surrounded him. We often picture the Vietnam War as a stripped down primitive struggle. Man versus nature, man versus man. But for the vast majority of troops stationed in the major base camps, the war was a bizarre exercise in consumerism.

It was the PX war, the post exchange. By 1969, the United States military was operating a retail network in South Vietnam that rivaled Sears or JC Penney. The sprawling PX at the long bin post was a warehouse of American industrial might. Inside the air conditioning hummed a lullaby of civilization.

A soldier could walk in from a patrol, scrape the red clay off his jungle boots, and purchase a Nikon camera, a TA reeltore tape deck, a Rolex Submariner watch, or a bottle of Chanel number five for a girl back in Cleveland. This was the surreal dislocation of the forward operating base. You were fighting a gorilla army that wore sandals cut from tire tread and lived on a cup of rice a day.

Yet inside the wire, you were surrounded by the excess of the greatest capitalist economy on earth. The logistics numbers are staggering. In 1968 alone, the Army and Air Force Exchange Service in Vietnam generated sales of over $300 million. That is nearly $3 billion in today’s currency. They sold 250,000 radios. They sold 180,000 cameras.

They sold millions of cases of beer. The beer is important. It was the lubricant of the base camp. Carling black label Budweiser Schlitz. It arrived in pallets stacked 10 ft high baking in the sun on the docks of Cameron Bay before being airlifted to the interior. But this abundance created a cruel geography of envy.

If you were a clerk at Tansson Air Base, you slept on a cot with sheets, you had a fan, and you could buy a cold Coke for 10 cents. If you were a grunt on a fire support base in the Asia Valley, luxury was a pair of dry socks. Let us zoom in on the fire support base. The FSB. This is where the abundance of the rear collided with the scarcity of the front.

Life on an FSB was defined by the log bird, the resupply helicopter. It was the heartbeat of the base. When the weather socked in, when the monsoon rains turned the sky into a solid gray sheet for 3 days, the base began to starve. Not just for food, but for the tools of war. Water was the primary currency. On a hilltop firebase, there is no groundwater.

Every drop had to be flown in. It arrived in bleets, giant black rubberized bladders that looked like beached whales slung underneath a CH47 Chinook. When the Bivet landed, it was an event. Men would scramble with 5gallon jerry cans. The water was hot. It tasted of rubber and iodine purification tablets. It was never cold. Drinking it was a chore, not a refreshment.

If the bivet didn’t come, you didn’t wash, you didn’t shave. Hygiene on the firebase deteriorated rapidly. This brings us to the jungle rot. It was a pervasive, inescapable fact of life. The combination of 90% humidity, constant sweat, and abrasive uniforms turned the human skin into a petri dish. Ringworm, hookworm, immersion foot.

Soldiers would wake up in their bunkers to find their boots had grown a layer of green mold overnight. They would take off their socks and peeling skin would come with them. The medics, the docks, waged a constant losing battle against fungus. They dispensed tubes of antifungal cream that the troops called courtesy of the lowest bidder. It rarely worked.

The only cure was to get dry. And in the central highlands during the rainy season, dry was a fantasy. Food on the firebase was a cycle of monotony. Sea rations, charlie rats. There were 12 menus. Everyone had a favorite and everyone had a hatred. Ham and lima beans, universally reviled as ham and motherfucers.

Beans and franks, spaghetti with meatballs. The ritual of eating was specific. You sat on a sandbag. You opened the can with a P38, a tiny hinged piece of metal that every soldier wore on his dog tag chain. The P-38 was perhaps the most reliable piece of equipment in the entire war. It never jammed. It never needed batteries.

You didn’t just eat the seation. You hacked it. You used a pinch of C4 explosive. Just a marblesized ball pinched from a claymore mine to heat it. C4 burns hot and fast, intense enough to boil a can of coffee in seconds. The soldiers knew the chemistry better than the scientists. They knew that burning C4 released toxic fumes, so you didn’t lean over it.

They knew that if you stomped on it to put it out, it might detonate, so you let it burn out. Contrast this with the Division base camp. At Chuli or Plecu, the mess halls were cavernous wooden buildings. They served a rations, fresh food, but the freshness was relative. Eggs were often powdered, milk was reconstituted, but they had ice.

Ice was the ultimate status symbol. The US military spent millions manufacturing ice in tropical heat. A block of ice on a firebase was a miracle. It was usually flown in by a sympathetic pilot who had wrapped it in a poncho. When it arrived, the men would chip at it with bayonets, putting shards into their warm canteen water, savoring the shock of the cold against their teeth.

It was a sensory reminder that a world outside the jungle still existed. But the physical conditions were only half the story. The psychological environment of the base was a pressure cooker. Boredom was the enemy. We see movies of constant combat, but the reality of the base was 99% waiting. Waiting for the patrol to come back, waiting for the rain to stop, waiting for the mortar siren.

This boredom bred a specific kind of counterculture. By 1969, the discipline of the Wuwa or Korea era army was fraying at the edges. In the privacy of the bunkers, the hooches, a different army emerged. Music was the soundtrack. The armed forces Vietnam network, AFVN, broadcasted officially sanctioned news and music, but the soldiers had their own ecosystem.

Akai and Teik realtore tape decks were everywhere. The music was a tribal signifier. In Soul Alley, the section of the base dominated by black troops. James Brown and Artha Franklin blasted from the speakers. The DAP became the greeting complex ritualized handshakes that could last 30 seconds. A secret language of solidarity that excluded the white officers.

In the white hooches, it was Credence Clearwater revival, the Doors, Hrix, and country music for the boys from the south. The sonic landscape of the bass was a cacophony of conflicting cultures. And then there were the drugs. We cannot talk about bass life without talking about the chemical alteration of reality.

In 1965, the drug of choice was beer. By 1968, it was marijuana. By 1970, it was heroin. The marijuana in Vietnam was potent, far stronger than the ditch weed back in the States. It was often dipped in opium. On the firebases, it was smoked through the barrel of a shotgun, a practice literally called shotgunning. A soldier would blow smoke into the brereech, and another would inhale from the muzzle.

It was a grimly ironic misuse of a weapon of war. Why did they do it? Not just for rebellion. They did it to numb the sensory overload, to dull the fear, to make the time pass. In the rear areas, the drug trade was brazen. Hooch maids, the Vietnamese women hired to clean, would bring packs of pre-rolled joints and cigarette cartons.

The officers knew, the MPs knew, but unless it affected combat readiness, it was often ignored. It was a containment strategy. Let the men blow off steam so they don’t blow up the base. But the racial tensions were not always contained. The rear echelon was where the race war back home spilled over into the war abroad. In the bush under fire, color didn’t matter.

You relied on the man next to you to suppress the enemy. But back at the base, the hierarchy returned. Black soldiers disproportionately drafted and assigned to combat roles returned to base camps to see Confederate flags hanging in white hooches. Brawls in the enlisted men’s clubs were common. Flashlights against Jaws, knives pulled in the latrines.

The base was a pressure cooker of American social dysfunction, superheated by the tropical sun. Let’s look at the infrastructure of waste, the [ __ ] burners. If there is one universal memory for the Vietnam veteran, it is the smell of burning excrement. In the temporary bases, there was no plumbing. The latrines were simple wooden boxes over cut off 55gallon drums.

Each morning, the low men on the totem pole, usually the new guys, the FNGs, fuking new guys or those on disciplinary detail, had to pull the drums out. They would drag them to a clearing, pour diesel fuel into the sludge, and ignite it. But wet sludge doesn’t burn easily. It requires constant stirring.

Soldiers stood there with sticks, stirring the burning waste as thick, black, oily smoke billowed into their faces. The smell stuck to your skin, your hair, your uniform. It was the smell of the war’s digestive system. It was a humiliating, primitive task performed in the shadow of multi-million dollar radar arrays.

The contrast between high techch and lowife was everywhere. You had the sniffer missions, helicopters equipped with ammonia sensors designed to detect the smell of enemy urine in the jungle. High technology. Yet on the ground, American soldiers were burning their own waste in barrels because they couldn’t build a septic tank. This was the development of the war.

A sprawling, messy, contradictory evolution. As the years went on, the bases became more permanent, more comfortable, and more dangerous. The perimeter was the defining line, the wire. A standard fire support base had three layers of defense. First the bunkers, then the trench line, then the wire, tanglefoot, low wire to trip you.

Concertina, coils of razor wire, and the claymores. The M181 Claymore mine was the soldier’s best friend and worst nightmare. A curved block of plastic explosive embedded with 700 steel ball bearings. When detonated, it sent a fan of steel shredding everything in a 60° arc. Every evening at stand 2, the base shifted from a workplace to a fortress.

Soldiers moved to the perimeter. They checked the clackers, the firing devices for the claymores. They set the trip flares. The night was a different country. During the day, the base belonged to the Americans. The helicopters ruled the sky. The trucks ruled the roads. But at night, the base shrank.

The jungle crept closer. on the perimeter. You didn’t look. You listened. You listened for the snap of a twig, the sound of wire being cut. The NVA sappers were ghosts. They stripped down to their underwear, covered their bodies in grease or charcoal to avoid reflection and insects, and crawled. They could crawl through a field of dry leaves without making a sound.

They could rotate a claymore mine so it faced back at the Americans without tripping the wire. The soldiers on guard duty popped hand illums, handheld flares, or called for illum from the mortar pit, a thump from the pit, a weight of 20 seconds, and then a pop high above. A parachute flare would drift down, bathing the landscape in a swaying artificial daylight.

The shadows moved. The trees looked like men. The rocks looked like trucks. Paranoia was the default state. In the Division base camps, the threat was less personal, but more massive. Rocket attacks. the 122mm Soviet rocket. It was a terror weapon. It arrived without warning. A supersonic shriek, then an explosion that could level a hooch.

Soldiers in Daang or Bian Hoa developed a Pavlovian response. At the first sound of the siren, or the first crack of an impact, they were out of their bunks and into the bunkers. You slept in your underwear, but you grabbed your flack jacket and helmet. The bunkers in the rear were concrete pipes buried in the earth or sandbag structures.

You sat there in the dark listening to the explosions walking across the base. Crump, crump, crump. You counted. You waited. You smoked. Sometimes the rockets hit the ammo dump. When the ammo dump at Daang or Long Bin went up, it was like a nuclear detonation. Fireballs rose thousands of feet into the air. Secondary explosions cooked off for days.

artillery shells, millions of rounds of small arms ammo, rockets, all destroying themselves. The soldiers watched it with a mix of awe and horror. It was the most expensive fireworks display in history. But amidst the rockets and the rot, there was the world, the connection to home. Mail call was the holy hour. When the mailbag was dumped out, the noise of the base stopped.

A letter from a girlfriend, a tape from mom, a package of cookies that had been crushed into powder. It didn’t matter. It was proof that you still existed outside of the green machine. But the letters also brought pain. Dear John letters were an epidemic. A soldier would get a letter saying, “I can’t wait anymore.” Or, “I met someone at college.

It devastated morale.” A man who received a Dear John letter was a liability on patrol. He was distracted. He was fatalistic. His buddies would watch him closely. The world was changing while they were gone. The soldiers who arrived in ‘ 65 came from a country that supported the war. The soldiers arriving in ‘ 69 came from a country that was burning draft cards.

They read about the protests in Stars and Stripes. They saw the pictures of long-haired students screaming at policemen. They felt abandoned. They were stuck in a firebase on the Cambodian border fighting for a country that seemed to despise them. This isolation drove the tribes of the base closer together.

the squad, the platoon, the hoochmates. You might hate the war. You might hate the army, but you loved the guy sleeping on the cot next to you. You shared your water. You shared your ammo. You shared your fear. And you shared the work. The endless, backbreaking work of maintaining the base. The base was a living organism that wanted to die.

The sandbags rotted, the trenches collapsed, the vegetation grew back overnight. If you weren’t on patrol, you were on a work detail. Burn [ __ ] fill sandbags, paint rocks. The absurdity of painting rocks white to line the path to the HQ bunker while the enemy was planning to overrun you was not lost on the grunts.

It was the army way. Busy hands don’t have time to mutiny. But the greatest logistical feat was the movement of men. The Freedom Bird, the chartered commercial airliner that took you home. The countdown to the Freedom Bird was the obsession of every soldier. The short- timers calendar, a drawing of a nude woman divided into 365 sections colored in day by day or a stick with notches.

When a soldier got short, less than 30 days left in country, he was treated differently. He was short. He was lucky. He was nervous. The fear of dying on your last day was a tangible weight. Don’t send me out, Sarge. I’m short. And often the sergeants would keep them on the base, put them on the radio, keep them safe. But safety was an illusion.

Let’s zoom in on a specific date. February 1969, post Tet. The American command believes they have secured the major bases. They believe the Vietkong is decimated. They are comfortable. The base at Long Bin is quiet. The perimeter lights are humming. The drug use is high. The guard towers are watching the wire, but the guards are tired.

They are listening to the radio. They do not see the grass moving. They do not see the wire cutters. The enemy had studied the base life, too. They knew the shift changes. They knew the blind spots in the lights. They knew that the Americans were addicted to their comforts, to their routines. And they use that comfort as a weapon.

The sapper is the ultimate predator of the base. He does not need a logistics tail. He does not need a helicopter. He needs a pair of shorts, a satchel charge, and an AK-47. He turns the American strength, the vast sprawling size of the base into a weakness. You cannot watch every inch of a 20-m perimeter.

As we move toward the climax of this story, we must understand that the base was not a fortress. It was a trap. The walls kept the world out, but they also kept the soldiers in. And when the walls were breached, the psychological shock was total. The illusion of safety is about to be shattered.

The music in the club is about to be drowned out by the scream of incoming. The air conditioner is about to stop. The lights are about to go out. 02117 hours. The perimeter of fire support base gold, Tyin Province. The darkness is total. The moon is obscured by heavy cloud cover. Inside the wire, 300 Americans are sleeping, playing cards, or staring into the black void.

They do not hear the snapping of the trip wire because the sapper does not snap it. He holds it. The North Vietnamese sapper, the Dak Kong, was the apex predator of the base war. He was not a conscript peasant. He was a highly trained specialist who spent months practicing on mock-ups of American bases. He knew how to breathe through a bamboo tube while submerged in a muddy ditch.

He knew how to cut barbed wire so that the tension didn’t release with a twang, but unspooled silently like a dying snake. He wore only shorts, his skin coated in a mixture of grease and charcoal to make him slippery and invisible to the naked eye. He is inside the wire. He is 10 ft from a bunker where two gis are sharing a cigarette.

This is the moment the illusion of the secure rear area evaporates. The attack does not begin with a roar. It begins with a thump. The sound of a satchel charge, canvas bags filled with TNT and a friction fuse. Landing on the corrugated metal roof of the tactical operation center. 3 seconds later, the world ends. The explosion flattens the command bunker.

The shock wave blows out the eardrums of every man within 50 m. Before the dust settles, the B40 rockets start coming in. The green tracers of AK-47s erupt inside the perimeter. Panic. Absolute disorienting panic. This is the chaotic reality of a base overrun. Soldiers wake up to the sound of screaming.

They grab M16s and scramble out of hooches in their underwear, bare feet cutting on gravel. There is no front line anymore. The enemy is everywhere. The enemy is in the mess hall. The enemy is by the showers. The American response is a spasms of overwhelming violence. The call goes out. Blue Max, Blue Max, or Broken Arrow.

Within minutes, the sky above the base turns into a ceiling of fire. The AC-47 spooky gunship arrives. This is a converted cargo plane mounting three miniguns. It orbits the base in a lazy left-hand turn, pouring fire down at a rate of 6,000 rounds per minute. From the ground, it looks like a solid red laser beam connecting the airplane to the Earth.

It sounds like a giant canvas ripping. Every fifth round is a tracer, but there are so many bullets that it looks like a waterfall of light. The spooky turns the earth just outside the wire, turning the jungle into mulch. Inside the wire, the fight is handto hand. It is brutal, intimate, and confused. Americans are shooting at shadows.

Friendly fire incidents skyrocket. In the confusion, a soldier sees a figure running near the ammo dump. He fires. He kills a cook running for a bunker. This is the dirty secret of the night attack. The chaos kills as effectively as the enemy. But the base has a system for this too. The medical evacuation, the dust off.

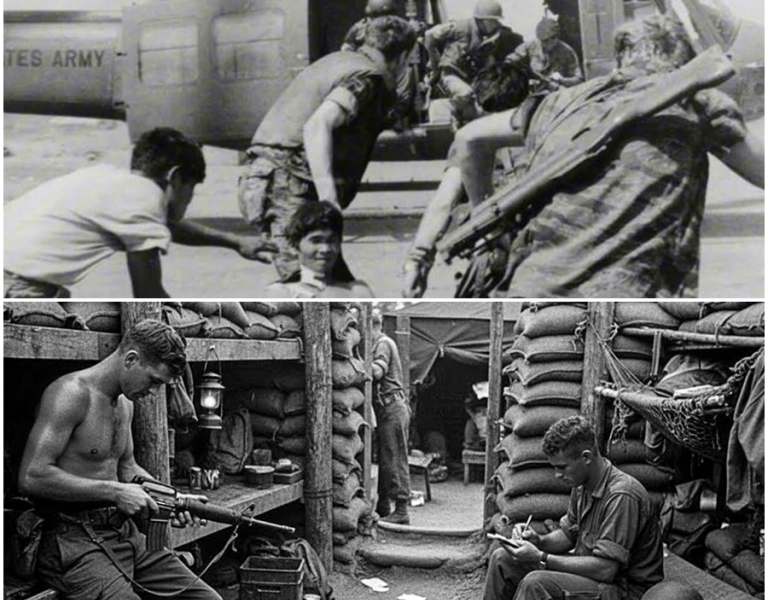

If the logistics chain was the muscle of the war, the dust off was its soul. Major Charles Kelly, the father of modern medevac, established the doctrine, when I have your wounded, they’re not going to die. He died proving it. By 1969, the system was a miracle of efficiency. A soldier takes a piece of shrapnel to the gut on the perimeter.

His buddy screams, “Med medic.” A corman, a 19-year-old kid with a bag full of morphine and bandages, crawls over. He slaps a compress on the wound. He gets on the radio. Dust off. Dust off. This is Highlander 6. Request urgent medevac at my location. In the air, a UH1 Huey marked with a red cross banks hard. The pilots of these birds were arguably the bravest men in Vietnam.

They flew without guns. They flew into hot LZ’s where the green tracers were thickest. The bird comes in. The noise is deafening. The whoop whoop of the blades mixing with the crack of incoming fire. The skid touches the mud. The wounded man is thrown aboard. The bird lifts. From the moment of injury to the operating table, 45 minutes.

This was the golden hour. In World War II, it took hours or days to get a wounded man to a surgeon. In Vietnam, if you made it onto the helicopter alive, you had a 98% chance of survival. The helicopter lands at a specialized medical base, a MASH, or an evac hospital, like the 12th Evac at Coochi or the 95th at Daang.

Here, the contrast is even more jarring. The helicopter lands on a concrete pad. The doors slide open. The wounded soldier, still covered in the mud of the firebase, is rushed into a triage room. Bright fluorescent lights, air conditioning, the smell of isopropyl alcohol and bedadine, nurses in clean fatigues, surgeons listening to rock and roll on tape decks while they work.

A soldier could be in a firefight at 300 bleeding out in the dirt. And by 0400, he is under anesthesia in a sterile room that looks like a hospital in Chicago. He wakes up in clean sheets eating jell-o. The psychological disconnect is shattering. He looks at his hands, scrubbed clean of the war, and wonders if the last 3 hours actually happened.

But back at the base, the sun comes up. The morning after an attack is a grim ritual. The adrenaline fades, replaced by a heavy, gray fatigue. The spooky gunships have returned to base. The smoke is still rising from the burntout bunkers. Now comes the police call, the cleanup. Soldiers walk the line with ponchos.

They are picking up the pieces of the war. They find the bodies of the sappers in the wire. They find the bodies of their friends. They drag the enemy bodies to a designated spot for intelligence to photograph and count. The body count was the metric of success. So, the dead were tallied like inventory. Then the bulldozers come out. They push the dirt over the craters.

The engineers bring out new plywood and corrugated metal. By 1200 hours, lunch is served. This is the most terrifying resilience of the forward operating base. It resets. The hole in the messaul roof is patched. The generator is fixed. The mail is sorted. The war continues. But the men are different.

The illusion of safety is gone. Every shadow is a sapper. Every noise is a rocket. The thousandy stare isn’t just from combat patrols. It comes from the realization that there is no sanctuary. And it wasn’t just the enemy that killed you on a base. It was the negligence. In the vast industrial machinery of Vietnam, accidents were a leading cause of death.

19% of all US casualties in Vietnam were non-hostile. Truck crashes. The roads were narrow, slick with rain, and crowded with kids. A deuce and a half truck flips into a rice patty. Three dead. A helicopter tailrotor clips a revetment during a routine supply run. The blade disintegrates, sending shrapnel through the crowd, waiting for mail. Two dead.

drug overdoses. By 1970, the heroin sweeping the bases was 95% pure. Soldiers used to smoking weak marijuana would snort a line of number four heroin and their hearts would stop instantly. They would be found in the latrines, blue-faced, needle or straw still in hand. Fraggings. This is the darkest chapter of the base life.

As the war became unpopular and the draft scooped up men who had no desire to be there, the bond between officer and enlisted man fractured. If a lieutenant or a sergeant was deemed too aggressive, if he volunteered his platoon for too many dangerous patrols, he might find a grenade pin on his pillow. A warning, if he didn’t listen, the next grenade would come into his hooch at night with the pin pulled.

Between 1969 and 1971, there were nearly 900 confirmed and suspected fragging incidents, 86 deaths, 700 injuries. It was a war within a war. Officers in rear areas began to sleep with their doors locked and their pistols loaded, terrified not of the Vietkong, but of their own men. The base designed to project power outward was rotting from the inside.

Let’s look at the exit strategy. The 365th day, the derp, the date eligible for return from overseas. When a soldier had 72 hours left, he stood down. He was pulled from the field. He turned in his rifle. He turned in his flack jacket. He was processed. He went to a center at Long Bin or Tons.

He was given a new uniform. Class A khakis or fresh fatigues. He was given a steak dinner. He was given a lecture on how to behave back in the world. Don’t talk about the war. They won’t understand. Don’t dive for cover when a car backfires. Be polite. Then he boarded the Freedom Bird, a chartered United Airlines or Panama Jet.

Steuartess’s with round eyes and perfume. Cushioned seats. The moment the wheels left the runway at Tanon was a religious experience. A cheer would go up. A primal screaming release of one year of held breath. As the plane climbed, the green curve of Vietnam fell away. The red craters, the brown rivers, the sprawling bases.

It all shrank into a map. But they carried the base with them. They carried the noise, the smell of burning diesel and [ __ ] the guilt of leaving their friends behind, the sound of the zipper on a body bag. They landed in San Francisco or Seattle. They walked off the plane and into a country that had moved on.

They went from the most intense, hyperreal experience of their lives to a society that was arguing about disco and gas prices. The transition was too fast. There was no decompression. One day you are burning leeches off your legs in a monsoon. 24 hours later you are sitting at a kitchen table in Iowa, staring at a glass of cold milk, listening to the refrigerator hum, waiting for the rocket siren that never comes.

The forward operating base was more than a place. It was a state of mind. It was a factory that processed human beings, consuming their innocence and outputting trauma. In the final section of this story, we will look at the legacy of these bases. What happened to the millions of tons of concrete? What happened to the children fathered by American gis and left behind? And how do the men who lived there remember the city in the jungle today? We will confirm our thesis that the American way of war, heavy logistical, comfortable, was both a triumph of engineering and a

failure of understanding. We built a house in the jungle, but we never owned the land. April 30th, 1975 0753 hours. The last helicopter lifts off the roof of the US embassy in Saigon. But the bases, Long Bin, Daang, Kaman Bay, had been emptying for years. The Vietnamization policy meant handing over the keys to the South Vietnamese army.

This brings us to the climax of our story, the abandonment. Imagine standing in the center of Long Bin Post in 1973. It is a ghost town of epic proportions. The swimming pools are drained and cracking in the sun. The basketball hoops are rusting. The air conditioning units have been ripped out of the walls.

The Americans didn’t just leave. They engaged in a frenzy of deconstruction. We call it retrograde. We shipped millions of tons of equipment back to the States or gave it to the ARVN, Army of the Republic of Vietnam. But we couldn’t take the concrete. We couldn’t take the roads. When the North Vietnamese tanks finally rolled through the gates of these super bases in 1975, they found the shell of a civilization.

They found barracks that could house thousands now silent. They found warehouses empty of everything but dust. The NVA soldiers, men who had lived in tunnels and eaten rice balls for a decade, walked through these complexes in disbelief. They saw the flush toilets. They saw the electrical grids. They saw the sheer wasteful magnitude of what their enemy had required just to exist.

This moment reveals the central irony of the war. We built the infrastructure of a modern nation state to fight a war. But we built it for ourselves. When we left, the power grid failed. The generators ran out of fuel. The ice machine stopped humming. The American city in the jungle didn’t fall to enemy fire. It simply evaporated because the plug was pulled.

The thesis is confirmed. The forward operating base was not a fortress. It was a life support system for an organism that could not survive in the Vietnamese environment on its own. The moment the connection to the logistics tale in California was severed, the base died. But the consequences of the base life did not end with the fall of Saigon.

They rippled forward in time. Resolution. First, the environmental scar. The bases were heavily sprayed with herbicides to keep the perimeter clear. Agent Orange, dioxin. It soaked into the soil of the fire bases. It washed into the water supply of the division camps. 50 years later, the hot spots of dioxin contamination in Vietnam are almost perfectly overlaid with the maps of the major US air bases, Bianoa, Daang, Fukat.

The children born in the villages surrounding these former bases today still suffer from birth defects at rates significantly higher than the rest of the country. The base is gone, but the poison remains in the mud. Second, the human legacy. The Amorasians. The base economy relied on local labor, housemaids, laundry girls, bar girls.

Relationships formed. Some were transactional. Some were genuine love affairs doomed by geopolitics. When the freedom birds flew the soldiers home, they left behind an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 children born of American fathers and Vietnamese mothers. These children grew up in the shadow of the abandoned bases.

They had American faces, blue eyes, light hair, black skin in a country that had just defeated America. They were ostracized. They were called children of the dust. They were the living ghosts of the occupation. They were the ultimate unplanned output of the base system. And finally, the veterans, the men who lived in the fire bases and the hooches, brought the habits of the base home with them.

You talk to a Vietnam vet today, 50 years later, and you see the phantom architecture of the FOB. He might still sleep with the door facing the wall. He might still be unable to tolerate the sound of fireworks. He might still hoard food or water, a subconscious reaction to the fear of the supply line being cut. The REM versus grunt divide softened with age, but it never fully went away.

At reunions, the guys who hump the boonies still look at the guys who had air conditioning with a mix of suspicion and brotherhood. They are united by the location, but divided by the experience. But they all share the memory of the noise, the specific acoustic signature of the war, the wump of the mortar, the crack of the M16, the thump thump thump of the Huey.

Today, if you go back to Vietnam, the landscape has reclaimed the war. I want you to picture the sight of fire support base rip cord today. The jungle has returned. The triple canopy rainforest has swallowed the trenches. The sandbags have long since disintegrated into the red clay. You have to look hard to find the evidence.

A rusted sea ration can half buried in a root system. A fragment of a blast wall covered in moss. A shallow depression in the earth where a boy from Kansas once sat and prayed for the sun to come up. The super bases have been repurposed. Long Bin is now an industrial park. Factories making shoes and electronics stand where the barracks used to be.

The runway at Daang is an international airport, welcoming tourists to beach resorts. The concrete we poured is now the foundation of Vietnam’s economic rise. The irony is absolute. We tried to bomb them into the Stone Age, but we ended up building the foundation for their modernization. Epilogue. The story of the forward operating base is a warning.

It is a testament to the American belief that we can engineer our way out of any problem. We believed that if we brought enough bulldozers, enough ice cream, and enough firepower, we could civilize the war. We thought we could insulate our soldiers from the reality of the conflict by building little Americas behind the wire.

But war is osmotic. It seeps through the wire. It gets into the water. It gets into the blood. We learned that you can air condition a barracks, but you cannot air condition a war. You can pave the jungle, but you cannot pave over the human heart. The soldier in Vietnam lived in two worlds. One was a world of technological dominance, of hot showers and cold beer.

The other was a world of primal fear, of sharpened bamboo stakes and silence. The tragedy was not that these two worlds collided. The tragedy was that we thought the first world could save us from the second. It didn’t. November 11th, 2024. A veteran stands at the wall in Washington DC. He touches a name. He closes his eyes. He is not in DC.

He is back at fire support base Coral. It is raining. He can smell the diesel. He can smell the rot. He can hear the generator humming in the dark. The base is closed. The war is over. But for him, the perimeter is still manned.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.