They Sent 92 Tiger Tanks to Stop Patton — Fewer Than 5 Survived

September 1944, somewhere in eastern France, a 23-year-old former auto mechanic from Ohio named Eddie Kowalsski sat inside a Sherman tank that weighed 33 tons and had armor thinner than a kitchen countertop compared to what was waiting for him down that road. Eddie had been a tank driver for exactly 4 months.

Before the war, he fixed Chevrolets at his uncle’s garage in Cleveland. He could rebuild a transmission blindfolded. He knew engines the way a surgeon knows the human heart. But nothing in Cleveland had prepared him for what German intelligence had just placed directly in his path. 92 Tiger tanks, the most terrifying weapon rolling on treads in the entire Second World War.

Each one weighed 56 tons. Each one carried an 88 mm cannon that could punch through Eddie’s Sherman like a fist through wet cardboard from over a mile away. At that range, Eddie’s 75 mm gun couldn’t even scratch the Tiger’s front armor. The math was simple and it was brutal. One Tiger killed four Shermans on average before going down.

92 Tigers meant the potential destruction of nearly 400 American tanks and over 1,500 American lives. German high command was betting everything on this single deployment. Stop Patton. Stop the Third Army. Buy enough time to reorganize the crumbling Western Front. On paper, 92 Tiger should have done exactly that. On paper, Eddie Kowalsski and thousands of men like him should have died in the fields of eastern France that September.

They didn’t. When the smoke cleared less than 72 hours later, fewer than five Tigers were still operational. The rest were burning abandoned, captured, or blown apart. And a former auto mechanic from Cleveland played a role that military historians are still studying today. This is how it happened. To understand why Germany made this desperate gamble, you need to understand how badly things had gone wrong for them by late summer 1944.

The Allied invasion at Normandy on June 6th had cracked open Fortress Europe. But it was what happened after Normandy that truly terrified the German generals. For weeks after D-Day, the fighting in the Hedro country of Normandy had been a grinding, bloody stalemate. Allies were gaining yards, not miles. German defenders used the thick hedge rows and narrow lanes of the Bage to create killing zones that neutralized Allied numerical superiority.

American casualties were staggering. Some infantry divisions suffered 100% turnover in their rifle companies within weeks. Tanks were being destroyed faster than they could be replaced. Then everything changed. Operation Cobra, launched on July 25th, 1944, blew a hole in the German lines west of St. Low.

And through that hole poured the most aggressive armored force in the Allied arsenal, General George S. Patton’s Third Army. Patton didn’t just advance. He exploded across France. His tank columns covered distances that German planners had considered impossible. 30 m in a day, [snorts] 50 m in a day. Towns that German commanders expected to hold for weeks fell in hours.

Entire German divisions that were supposed to form defensive lines found themselves encircled before they could even dig fox holes. By mid August, the German position in France was collapsing. The filet’s pocket trapped tens of thousands of German soldiers. Paris was liberated on August 25th, and Patton kept pushing east toward the German border itself, moving so fast that his own supply lines could barely keep up.

The speed was unprecedented. Nothing in the war on any front had moved this fast. German commanders who had fought on the Eastern Front against the Soviets said Patton’s advance was faster and more disorienting than anything the Russians had ever achieved. The casualties told the story. In August alone, the German army in the West lost over 300,000 men killed, wounded, or captured.

They lost thousands of tanks, guns, and vehicles. Entire units simply ceased to exist. Staff officers at German headquarters were moving pins on maps so fast that the maps became useless before they were updated. Patton’s third army alone had captured more territory in two weeks than the entire Allied force had taken in the two months since D-Day.

Something had to be done. Something dramatic. Conventional defenses were failing. Infantry divisions were being overrun. Anti-tank guns were being flanked before they could fire a shot. The German generals needed a weapon that could stop Patton’s armor cold, that could destroy enough Shermans to force even the most aggressive American commander to pause.

They needed the Tiger. But everything was about to change because of men like Eddie Kowalsski. Men nobody had ever heard of. Men whose names would never appear in history books, but whose actions would determine the fate of the most powerful tanks ever built. Eddie Kowalsski had enlisted the day after his 22nd birthday in 1943.

He wasn’t a hero. He wasn’t even particularly brave by his own admission. He was a mechanic who understood machines the way some people understand music intuitively completely at a level that went beyond technical knowledge into something almost like instinct. In basic training, his instructors noticed that Eddie could diagnose engine problems by sound alone.

He could tell you what was wrong with a tank engine from 50 feet away just by listening to it idle. When he was assigned to the Third Army’s tank cruise, his commanding officer put him as a driver. Not because Eddie was the best driver, but because having someone who understood the Sherman’s mechanical limits meant the tank could be pushed harder, faster, longer, without breaking down.

Eddie had survived his first combat in Normandy. He’d seen Tigers for the first time near Mortan in early August when the Germans launched their desperate counterattack. He watched from 800 yd as a single Tiger destroyed three Shermans from his company in less than 2 minutes. The shells went through the Shermans like they weren’t even there.

Crews burned alive. Eddie’s tank survived only because his commander ordered a retreat behind a hedge row before the Tiger could traverse its turret to their position. That night, Eddie couldn’t sleep. He kept thinking about the Tiger, not with fear, though there was plenty of that, but with a mechanic’s curiosity.

He’d seen how the tiger moved, how slowly it traversed, how long it took to reposition, how the engine sounded when it shifted gears, and something clicked in his mind. In the same way a diagnosis clicked when he heard a bad valve lifter back in Cleveland. The Tiger was powerful. Yes, but it was also a mechanical nightmare.

Eddie could hear it in the engine note. Could see it in how the tracks handled terrain. Could feel it in the way the massive turret struggled to track fastmoving targets. Eddie started talking to other tank crews. He started collecting information. How fast could a Tiger traverse its turret? About 60 seconds for a full rotation compared to 15 seconds for a Sherman.

How quickly could it accelerate? Barely at all. The Tiger went from zero to top speed like a freight train, slow and ponderous. What happened when a Tiger tried to move on soft ground? It sank. Its ground pressure was enormous despite wide tracks. Where was the armor weakest? The sides were about 80 mm less than half the frontal armor.

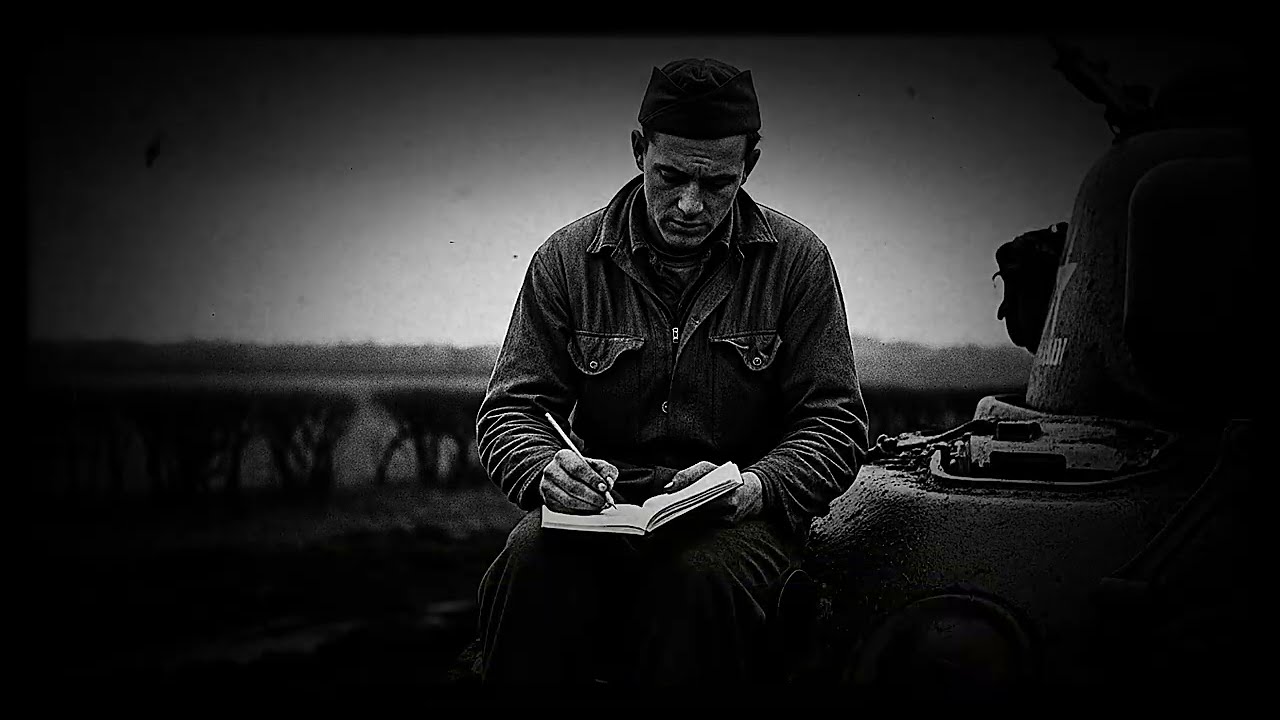

The rear was even thinner. The belly was vulnerable to mines. Eddie wrote all this down in a small notebook he carried in his coveralls. His tank commander, a lieutenant from Virginia named James Morrison, noticed what Eddie was doing. Instead of telling him to stop, Morrison started adding his own observations. Then other crew commanders joined in.

Within days, Eddie’s notebook had become an unofficial tactical manual, a collection of practical knowledge about Tiger weaknesses compiled by men who had faced them in combat. When this information reached Captain Robert Hayes, who commanded their tank company, Hayes didn’t laugh. He didn’t dismiss it.

He took Eddie’s notebook directly to battalion command. and battalion command took it to division and division took it to third army headquarters because what Eddie Kowalsski had done without any formal training and military tactics was essentially confirm what Patton had been preaching for months. The Tiger could be beaten not by building a better tank, not by matching it gun for gun and armor for armor, but by understanding its mechanical weaknesses and exploiting them ruthlessly.

The idea that a mechanic’s observations could influence armored tactics was considered ridiculous by some staff officers. These were West Point graduates, professional soldiers who had studied armored warfare for years. And here was a former Chevrolet mechanic, telling them how to fight tigers. Some officers wanted to dismiss it entirely.

One colonel reportedly said that if they needed a grease monkey to tell them how to fight, they might as well surrender now. But Patton was different. Patton understood something that many career officers did not. War is not won by credentials. It is won by knowledge applied at the right moment. And Eddie Kowalsski’s knowledge of machines combined with his direct combat experience against tigers represented exactly the kind of practical intelligence that wins battles.

Patton had his staff compile Eddie’s observations alongside their own intelligence reports. The result was a set of tactical guidelines that would be distributed to every tank unit in the Third Army. The core insight was devastatingly simple. Stop thinking of the Tiger as an invincible super weapon. Start thinking of it as a machine.

And every machine has weaknesses. Every machine breaks down. Every machine has limits. The Tiger’s limits were speed, fuel consumption, mechanical reliability, and turret traverse rate. A Sherman crew that understood these limits and fought accordingly could survive. A Sherman company that coordinated its attacks to exploit these limits could win.

Eddie didn’t know it then, but his notebook would help save lives in the battle that was coming because German intelligence had made their decision. 92 Tigers were being assembled, fueled, armed, and positioned directly across Patton’s line of advance. It was the largest single deployment of Tiger tanks against American forces in the entire war.

The Germans called it Operation Eisenhhammer, Iron Hammer. The plan was straightforward. Position the Tigers in three defensive lines across the most likely avenues of American advance. First line would engage and destroy the leading American armor. Second line would catch any units that broke through. Third line would serve as a mobile reserve to counterattack any flanking attempts.

Each line was supported by infantry anti-tank guns and what little artillery the Germans could still concentrate. On paper, it was a perfect defensive deployment. Three walls of the most powerful tanks in the world, each capable of destroying American Shermans at ranges where the Shermans couldn’t fire back effectively.

German planners estimated it would take Patton’s forces at least two weeks to break through, if they could break through at all. Two weeks would give Germany time to rush reinforcements from other sectors. Time to fortify the approaches to the Rine. Time to organize the kind of deep defensive belt that had held the Allies in Normandy for months.

That was the plan. What actually happened bore no resemblance to any plan. Patton’s reconnaissance units detected unusual German armored activity 3 days before the main engagement. Scout planes reported large numbers of heavy tanks moving into concealed positions. Signal intelligence intercepted fragmentaryary communications referencing Tiger units being redeployed from other sectors.

and ground scouts, including a team that Eddie Kowalsski’s company supported, identified Tiger track marks on roads leading to defensive positions. The initial deployment confirmed what they had discovered. American scouts counted at least 40 Tigers in forward positions with reports of more arriving.

This was not a routine defensive screen. This was a massive concentration of heavy armor, the largest Tiger deployment any American unit had ever faced. When the reports reached Patton’s headquarters, staff officers recommended caution. Slow the advance. Bring up additional forces. Plan a set piece assault with overwhelming numerical superiority.

Standard doctrine against fortified armor. Patton rejected every recommendation. His response became legendary among his staff. He reportedly said that stopping was exactly what the Germans wanted. Every hour he paused was an hour the tigers spent getting better positioned, better supplied, better prepared. The tigers were strongest when they were sitting still, hauled down in prepared positions with clear fields of fire.

So the last thing he intended to do was give them time to sit still. Instead, Patton did something that his own officers initially thought was insane. He accelerated the advance. He split his forces into multiple columns approaching from different directions. He requested every available fighter bomber squadron for close air support.

He moved his artillery forward to positions that were dangerously close to the expected engagement zone. And he sent orders down to every tank company in the Third Army, including Eddie Kowalsskis. The orders were clear. Do not stop when you encounter Tigers. Do not engage in long range duels. Close the distance. Use terrain. Call in artillery.

Call in air support. Attack the flanks. Keep moving. Always keep moving. Eddie read those orders sitting on the engine deck of his Sherman on a cool September evening. He looked at his notebook, dogeared and oil stained, filled with observations about Tiger weaknesses. Tomorrow he would find out if those observations were right.

Tomorrow 92 Tigers would try to stop Patton’s Third Army. But what neither Eddie nor anyone else in the Third Army knew was that the next 72 hours would become one of the most devastating defeats in the history of armored warfare. Not for the Americans, for the Tigers, and the battle hadn’t even started yet. In part two, we will see what happened when Patton’s tactics met Germany’s super weapon headon.

How a former auto mechanic’s instincts saved his crew in the first terrifying minutes of contact. How 92 Tigers were systematically hunted, flanked, and destroyed by an army that refused to play by the rules the Germans expected. And why the first 6 hours of battle turned into the worst nightmare German tank crews had ever experienced.

The Tigers were waiting, Patton was coming, and nothing would ever be the same. In part one, a former auto mechanic named Eddie Kowalsski compiled a notebook of Tiger tank weaknesses that reached Patton’s headquarters. 92 Tigers were positioned across Patton’s line of advance in the largest heavy armor deployment against American forces in the entire war.

Patton’s response was to accelerate, not retreat. His orders went out to every tank company. Close the distance. Attack the flanks. Never stop moving. But convincing tank crews who had watched Tigers destroy Shermans like tin cans to charge toward those same Tigers was another matter entirely because the men who would execute Patton’s orders had a problem that no tactical manual could solve.

They were terrified and that terror was about to collide with the biggest institutional obstacle Eddie Kowalsski had ever faced. A man who believed that mechanics should fix engines, not write tactics. And this is where everything got worse. Colonel Harold Brennan commanded the armored regiment that included Eddie’s company. Brennan was old army.

West Point class of 1928. He had served in North Africa, survived Casarine Pass, fought through Sicily, and landed in Normandy on D-Day plus three. He had earned every medal on his chest through blood and steel. and he had absolutely zero patience for a corporal who thought he knew more about fighting tanks than officers who had been doing it for 2 years.

When Captain Hayes brought Eddie’s notebook observations up the chain, Brennan’s reaction was immediate and volcanic. He called Hayes into his command post on the evening before the expected engagement and made his position perfectly clear. Captain, are you telling me that a tank driver, a mechanic, is advising my regiment on armored tactics against Tiger tanks? Hayes tried to explain.

The observations were sound. They matched Patton’s own tactical guidelines. The information about turret traverse rates, fuel consumption, mechanical vulnerabilities. It was practical intelligence gathered from direct combat experience. Brennan cut him off. I’ve been fighting German armor since Casarine. I lost 14 tanks at Casarine. I know what tigers can do.

And what tigers can do is kill Shermans. The answer to Tigers is not some grease monkeys notebook. The answer is concentration of force, proper reconnaissance, and disciplined fire and maneuver. Not whatever cowboy nonsense Patton’s headquarters is cooking up. Brennan’s objection wasn’t irrational. His experience at Casarine Pass in February 1943 had been catastrophic.

American forces had attacked German positions peacemeal without coordination and had been slaughtered. Brennan had learned a brutal lesson there. You don’t rush into a fight against superior armor. You plan carefully. You concentrate your forces. You attack with overwhelming numbers at a single point. What Patton was ordering, splitting forces into multiple columns, accelerating toward the strongest concentration of Tigers ever assembled, looked to Brennan exactly like the kind of reckless aggression that had gotten

hundreds of Americans killed at Casarine. He ordered Hayes to shove Eddie’s observations. Standard doctrine would be followed. The regiment would advance in concentrated formation, engage Tigers at range, and rely on numerical superiority. This was exactly the kind of fight Tigers were designed to win, and Brennan was about to order his men into it.

Eddie heard about the colonel’s decision from Lieutenant Morrison that same evening. Morrison was frustrated. He’d seen what Tigers could do at Morta. He knew that a concentrated formation advancing across open ground against prepared Tiger positions was a death sentence for the leading tanks. But Morrison was a lieutenant.

Brennan was a colonel. The chain of command existed for a reason. Eddie didn’t care about the chain of command. He cared about the men in his tank, the men in his company, the men who would die tomorrow morning if they drove straight at 92 Tigers in a neat formation that the German gunners would pick apart like target practice.

So Eddie did something that could have gotten him court marshaled. He went over Brennan’s head, but he didn’t go alone because Eddie had found an unexpected ally. Major Thomas Whitfield was the regiment’s operations officer, the S3. Whitfield was responsible for planning the regiment’s tactical movements, and he had been quietly studying the same intelligence that had produced Patton’s anti-tiger guidelines.

Whitfield was 31 years old, a former engineering student from MIT who had been commissioned through OCS in 1942. He understood machines. He understood systems. And he understood that Brennan’s plan would get men killed for no strategic gain. Whitfield had read Eddie’s notebook, not because Eddie brought it to him, but because Captain Hayes had quietly slipped it onto Whitfield’s desk 3 days earlier with a note that said simply, “The mechanic sees what we’re missing.

” Whitfield had verified Eddie’s observations against intelligence reports. The turret traverse rate was accurate. The fuel consumption data matched captured German logistics documents. The mechanical reliability estimates aligned with afteraction reports from units that had recovered disabled Tigers. When Eddie came to Whitfield’s tent that night, Whitfield was already working on an alternative plan.

not to replace Brennan’s orders entirely, but to modify them enough to give the regiment a fighting chance. Whitfield’s plan kept the basic structure of Brennan’s advance, but added critical elements. Advanced scouts would identify Tiger positions before the main force committed. Artillery would be pre-registered on likely Tiger positions and ready to fire within 90 seconds of contact.

Tank destroyers would be positioned on the flanks, not in the main column, ready to maneuver for side shots the moment Tigers revealed themselves. And crucially, no single company would advance alone across open ground. If one company drew fire, adjacent companies would immediately flank. The problem was that implementing this plan required Brennan’s approval, and Brennan had made his position clear.

Whitfield made a decision that risked his career. He contacted Third Army headquarters directly bypassing Brennan and requested that a representative from Patton’s staff be present for the morning briefing. The request was granted. Lieutenant Colonel David Abrams, one of Patton’s most trusted tactical advisers, would attend.

The next morning, September 12th, the briefing was tense. Brennan presented his plan. concentrated advance, masked armor, engage tigers at range with numerical superiority, standard doctrine. When Brennan finished, Abrams spoke. He didn’t criticize Brennan directly. Instead, he laid out third army intelligence on the German deployment.

Three lines of Tigers. Prepared positions with pre-registered kill zones. Infantry support with anti-tank weapons covering the gaps between Tiger positions. Estimated time to breach the first line under Brennan’s plan, 8 to 12 hours. Estimated American tank losses during that breach, 40 to 60% of the leading battalion. The room went silent.

Brennan’s face was stone. Abrams continued. Under Patton’s preferred approach, multiple axes of advance with combined arms coordination, the estimated breach time dropped to 4 to 6 hours. Estimated losses dropped to 15 to 25%. Still heavy, still painful, but survivable. Brennan argued back, “Those estimates assume perfect coordination.

In combat, coordination breaks down. Radios fail. Smoke obscures targets. Men panic. Concentrated force gives us mass. Mass wins battles. Abrams nodded. Mass wins battles when the enemy is dispersed. When the enemy is concentrated in prepared positions with the most powerful tank gun in the world, mass gives them a targetrich environment.

General Patton’s orders are clear, Colonel. Multiple axes, combined arms, speed. It wasn’t a suggestion. It was an order from third army command delivered politely but unmistakably. Brennan had no choice. He accepted the modified plan. But he made one thing clear to Whitfield afterward. If this goes wrong, Major, it’s your career and that mechanic’s stripes on the line, not mine. Whitfield didn’t blink.

He had 16 hours to prepare the regiment for the largest Tiger engagement in American military history, and the clock was already running. The morning of September 13th, 1944 broke gray and cool with a low fog sitting in the valleys of eastern France. The fog was a gift. It reduced visibility to less than 500 yd, which meant the tiger’s greatest advantage, their ability to kill at extreme range, was temporarily neutralized.

Eddie Kowalsski sat in his driver’s seat engine, idling, watching the fog swirl around the hull of his Sherman. Lieutenant Morrison was in the turret, scanning with binoculars that were useless in the Merc. The radio crackled with position reports from scout units ahead. First contact came at 0647. A scout team reported tiger positions along a rgeline approximately 1,200 yd ahead.

At least eight Tigers visible, probably more behind the ridge. They were hauled down. Only their turrets exposed above the terrain. Guns pointed directly down the main approach road, exactly where German intelligence had predicted American armor would come. Under Brennan’s original plan, the regiment would have advanced straight down that road.

The first company to crest the rise would have been visible to eight Tiger guns simultaneously. At 1,200 yds, the Tigers would have had roughly 45 seconds of unobstructed firing before the Shermans could close to effective range. Eight Tigers firing every 8 seconds meant approximately 45 rounds of 88 mm fire hitting the lead company before they could shoot back.

The math was annihilating. Instead, Whitfield’s plan went into effect. The lead company stopped short of the ridge. Artillery coordinates were transmitted. Within 3 minutes, 105 mm shells began falling on the Tiger positions. Not to destroy them. The shells couldn’t penetrate Tiger armor from above at that angle, but the explosions forced Tiger crews to button up closing hatches, losing the external visibility they needed to aim accurately at long range.

Simultaneously, Eddie’s company and two others peeled off the main road, moving through the fog along secondary tracks that the scouts had identified during the night. Eddie pushed his Sherman through a muddy farm lane, barely wide enough for the tank branches, scraping the whole visibility down to 200 yd.

His heart was hammering. Somewhere ahead and to his right, the Tigers were sitting on that ridge, their guns covering the main road, not expecting anything from this direction. At 0712, Eddie’s company emerged from a tree line 600 yardds to the left flank of the Tiger position. 600 yardds.

At that range, the Tiger’s side armor of 80 mm was vulnerable to the Sherman’s 75 mm gun. More importantly, the Tiger’s turrets were facing the wrong direction, pointed down the main road where artillery was still falling. Morrison gave the order to fire. Five Shermans from Eddie’s company opened up simultaneously on the exposed flanks of the Tiger positions.

Eddie felt his tank rock with the recoil. Through his periscope, he saw a flash against the side of the nearest Tiger. A hit, then another. The Tiger’s turret began to traverse toward them. That slow grinding rotation that Eddie had timed so many times in his notebook. 60 seconds for a full traverse. They had 60 seconds.

In those 60 seconds, Eddie’s company fired 23 rounds. Four Tigers were hit from the side. Two began to smoke. One exploded as ammunition cooked off inside. The fourth Tiger’s track was shattered, immobilizing it. The remaining Tigers on the Rgel line were now caught between artillery from the front and tank fire from the flank.

Their carefully prepared kill zone had become a trap, and they were inside it. At the same moment, P47 Thunderbolts arrived overhead. The fog had lifted enough for air operations, and Patton’s requested air support descended on the German positions with rockets and 500 lb bombs.

Two more Tigers were hit from above. One took a direct rocket hit to the engine deck and burst into flame. The crew bailed out and ran. Tank destroyers that had circled even wider than Eddie’s company now appeared on the Tiger’s right flank. M18 Hellcats, fast and lightly armored, but mounting 76 millimeter guns that could penetrate Tiger sidearm at combat range.

They fired and displaced, fired and displaced, never staying in one position long enough for the Tigers to engage them. Within 90 minutes of first contact, 11 of the estimated 15 Tigers in the first defensive line were destroyed, immobilized, or abandoned. American losses were four Shermans destroyed and two damaged.

The ratio that was supposed to be four Shermans per Tiger had been almost reversed. The first line was broken, but this was only the first line. Behind it, at least 60 more Tigers waited in the second and third defensive positions, and the Germans had been watching. They had seen their first line collapse in minutes instead of holding for days.

They were already adapting repositioning, closing the gaps that Eddie’s flanking maneuver had exploited. Colonel Brennan, watching the first engagement from his command halftrack, said nothing for a long time. Then he picked up the radio and called Whitfield. The mechanic’s information was correct about the traverse rate.

What else does he know about their second line? It was the closest thing to an apology Eddie Kowalsski would ever receive, and it was enough. Patton’s headquarters received the report within the hour. 11 Tigers destroyed in 90 minutes with minimal American losses. The response from Third Army was a single sentence that embodied everything Patton believed about warfare. Do not stop. Repeat.

Do not stop. The regiment pushed forward toward the second Tiger line. But the Germans had learned. They had repositioned their Tigers to cover multiple approaches, not just the main road. They had pulled infantry closer to the tank positions to prevent flanking maneuvers. They had dispersed their Tigers more widely to reduce the effectiveness of artillery concentrations.

The second line would be harder. And something else was happening that nobody on the American side knew about yet. A German signals unit had intercepted fragments of American radio traffic during the first engagement. They had heard the coordination between tanks, artillery, and air support. They had heard references to Tiger weaknesses.

And they had transmitted a report to German high command that would change how the remaining Tigers fought. The Germans were adapting. The easy victories were over. Eddie Kowalsski’s notebook had helped break the first line, but 60 Tigers remained, and their crews were no longer sitting in prepared positions, waiting for Americans to come to them.

They were moving, repositioning, setting up ambushes in locations the Americans hadn’t scouted, hiding in towns and forests where air support was useless and artillery was dangerous to use. The Tiger crews had received new orders from German command. Do not fight defensively. Do not hold positions. Hunt the Shermans. Use the towns. Use the forests. Use the knight.

Turn the Tigers weaknesses into strengths by fighting at close range where American coordination couldn’t save them. In part one, Eddie Kowalsski figured out how to fight Tigers. In part two, his ideas helped shatter the first defensive line. But in part three, the Tigers would stop being the hunted and start being the hunters.

The Germans were coming, not in defensive lines anymore. In ambush teams of two and three, hiding in every village and treeine between Patton and the Rine. The rules of the game had changed completely, and the real war was just beginning. A former auto mechanic named Eddie Kowalsski wrote a notebook about Tiger tank weaknesses.

That notebook helped reshape Third Army tactics. In the first engagement, Patton’s forces shattered the first German defensive line, destroying 11 Tigers in 90 minutes with minimal losses. The ratio that was supposed to favor Tigers had been reversed. But as part two ended, German signals intelligence had intercepted American radio traffic.

They heard the coordination. They heard references to tiger vulnerabilities. And they issued new orders to their remaining crews. Stop defending. Start hunting. 60 Tigers changed from stationary fortresses into mobile ambush predators hiding in villages and forests where American air support was blind and artillery was dangerous.

The easy part was over. The statistics that followed proved it. In the next 36 hours, American tank losses tripled compared to the first engagement. Eight Shermans were destroyed in a single afternoon by just three Tigers operating in ambush teams inside a French village. And now this was no longer an experiment in tactics.

This was a fight for survival on both sides. German command reacted to the destruction of their first defensive line with a speed that surprised American intelligence. Within hours of receiving the signals, Intercept General Fritz Berline, commanding the remnants of Panzer Lair Division and coordinating Tiger operations in the sector, convened an emergency meeting with his surviving Tiger Company commanders.

Bayerline was no fool. He had commanded tanks in North Africa under Raml. He had fought the British, the Americans, and he understood that clinging to doctrine when doctrine was failing meant death. The intercepted radio traffic told buyer line exactly what the Americans were doing.

Combined arms coordination, flanking maneuvers against Tiger side armor, artillery suppression to force crews to button up, air strikes on exposed positions. Every advantage the Tiger possessed in a prepared defensive position was being systematically neutralized. Bayerines orders were radical by German standards. Abandon the remaining two defensive lines.

disperse the Tigers into teams of two or three, move them into villages, forests, and urban areas where American air power could not operate effectively, and where artillery risked killing French civilians and destroying infrastructure the Americans themselves needed. Fight at close range, ambush, and withdraw.

Never stay in one position longer than 30 minutes. use the Tiger’s massive gun, not at long range where flanking was possible, but at point blank range inside towns where a single shot down a narrow street could destroy multiple vehicles. It was the opposite of everything Tiger crews had been trained to do. But it was brilliant.

Within 12 hours, the remaining 60 operational Tigers had vanished from their defensive positions. American scouts reported the second and third lines abandoned. For a brief moment, American commanders thought the Germans were retreating. They were wrong. The first ambush came at the village of Montlair. A column of six Shermans from Charlie Company advanced through the village’s main street.

Standard procedure. Infantry screening ahead tanks following in file. The lead Sherman reached the village square. A tiger was hidden inside a partially collapsed barn, its gun barrel protruding just 3 ft past the rubble. range was 80 yards. At 80 yards, the 88 millimeter round went through the front armor of the lead Sherman, through the engine compartment, and out the back plate.

The Sherman behind it, took a round through the turret before the crew even identified where the shot came from. The Tiger reversed out of the barn, crushing the rear wall, and disappeared down an alley before American tank destroyers could respond. Two Shermans destroyed. Zero damage to the Tiger. Time elapsed 45 seconds. This was the new war.

Three more ambushes followed that afternoon. A tiger hidden behind a farmhouse. Two tigers positioned at opposite ends of a crossroads, creating a crossfire. A single tiger concealed in a sunken lane that fired into the side of a passing column and then withdrew into woods. By evening, eight American tanks were destroyed and three damaged.

No Tigers lost. The combined arms approach that had worked so brilliantly against the first defensive line was useless in close terrain where every advantage belonged to the ambusher. But this was not the only problem facing Patton’s forces. Inside Third Army, a crisis was developing that threatened to undo everything Eddie’s observations had helped achieve.

The success of the first engagement had created overconfidence. Some company commanders, having seen Tigers destroyed relatively easily in the first battle, began treating all Tiger encounters as simple tactical problems. They stopped calling for artillery support. They stopped waiting for air cover. They advanced aggressively into terrain they hadn’t scouted, assuming that speed and flanking would solve every engagement.

It didn’t. it. The ambush at Montlair killed three men from Eddie’s own battalion. One of them was Corporal James Dunning Eddie’s loader, who had been transferred to another crew just two days earlier to replace a wounded man. Eddie found out over the radio. He sat in his driver’s seat and didn’t speak for an hour.

Colonel Brennan, who had initially opposed the modified tactics, now used the mounting casualties to push back against Patton’s approach entirely. He sent a report to division headquarters arguing that the dispersed Tiger tactics made combined arms coordination impossible and that the regiment should halt consolidate and wait for reinforcements before continuing the advance.

The report included the casualty figures from the ambushes, eight tanks, 23 killed, 14 wounded in a single afternoon. Division forwarded the report to Third Army. For 12 hours, there was silence from Patton’s headquarters. Eddie and every man in the regiment waited, not knowing whether the advance would continue or whether they would dig in and face weeks of grinding attrition against Tigers that appeared and vanished like ghosts.

Some officers privately blamed Eddie’s notebook for creating the overconfidence that led to the ambush losses. If the first engagement hadn’t gone so well, Cruz would have been more cautious. If Whitfield’s plan hadn’t worked so perfectly, commanders wouldn’t have become reckless. The mechanic’s observations had helped win the first battle, and some argued had contributed to losing the second.

Eddie himself wondered if they were right. Three men were dead. James Dunning was dead, and the Tigers were still out there, invisible, waiting. But then a message arrived that changed everything. Patton himself sent the response. not through staff channels. Directly over the command net in clear language that every radio operator in the regiment could hear.

The message was vintage patent blunt, profane and absolutely clear. Tigers hiding in villages means tigers have abandoned the open ground. They gave up their defensive lines. They are reacting to us. We do not stop because the enemy adapts. We adapt faster. New orders follow. The new orders arrived within the hour and they represented a tactical evolution that would become a case study at militarymies for the next 80 years.

Patton staff had analyzed the ambush pattern in real time. Tigers in villages needed narrow streets and buildings for concealment. They operated in pairs or threes. They fired and withdrew. The weakness was movement. A tiger reversing through a village was slow, loud, and visible.

It couldn’t hide once it fired, and it couldn’t reposition faster than radio could transmit its location. The new plan was simple and devastating. Every infantry squad advancing through a village would carry smoke grenades, and SCR536 handheld radios upon Tiger contact infantry would immediately pop smoke to obscure the Tiger sight line and radio the exact position.

Tank destroyers would not enter the village. They would be prepositioned at every exit road waiting. Artillery would fire white phosphorous rounds to mark the Tiger’s location from above. And P47s would orbit overhead, not to bomb the village, but to track any Tiger attempting to withdraw and hit it once it reached open ground.

The Americans were turning every village into a trap. If a tiger fired from inside a town, it revealed itself. Smoke cut its vision. Tank destroyers blocked its escape routes. Aircraft tracked it from above. The ambush predator became the ambush prey. September 15th, the village of St. Oan Leati, population 400, three streets, one church, two bridges.

American intelligence had identified probable tiger positions based on track marks and a report from a French farmer who had watched two tigers drive into barns on the east side of the village the previous night. Major Whitfield personally planned the engagement. Infantry from Baker Company entered the village from the west at 0530, moving in small teams along building walls, checking corners, marking potential Tiger hiding positions with chalk.

Tank destroyers from the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion positioned at every road leading out of the village. Four vehicles, four exits, no escape. Artillery battery registered on the village square and eastern approaches. P47s on standby at 8,000 ft. Eddie Sherman and three others waited 400 yd west of the village.

They were bait. Their job was to advance slowly along the main road presenting exactly the kind of target that Tiger ambush crews couldn’t resist. A column of Shermans approaching in file, the same formation that had been destroyed at Montlair. Eddie drove. His hands were steady, but his mouth was dry. He was the first tank in the column, the first target.

If a Tiger fired from inside the village, his Sherman would be the one it hit. Morrison sat above him in the turret, scanning windows and rooftops through his periscope. Nobody spoke. At 0614, Eddie’s Sherman reached the first buildings. The street narrowed. Walls rose on both sides. Exactly the killing ground a Tiger would choose. At 0617, the Tiger fired.

The round passed three feet above Eddie’s turret. Close enough that the shock wave cracked Morrison’s periscope. The Tiger was in a barn 120 yard ahead, its barrel visible through a gap in the doors. It had aimed for the turret and missed high. An 88 mm round that missed high by 3 ft. Eddie was alive by 36 in.

Morrison screamed into the radio. Tiger Barn, East Side, 120 yards Main Street. Everything happened simultaneously. Smoke grenades flew from infantry positions on both sides of the street. Within seconds, white smoke billowed across the road, cutting the Tiger’s line of sight. The Tiger fired again, blind the round, smashing through the wall of a house to Eddie’s left and exiting through the roof.

Eddie threw the Sherman into reverse and backed out of the kill zone at full speed. tracks grinding on cobblestones. Artillery opened up, not on the barn. On the roads east of the village, white phosphorous rounds burst in brilliant white clouds, marking every exit route. The P47s overhead banked hard pilots looking for movement.

Inside the barn, the Tiger crew made their decision. They couldn’t see. They couldn’t stay. They had to move. The Tiger’s engine roared. It crashed through the barn’s rear wall and turned onto a side street heading east toward the nearest bridge. It never reached the bridge. A tank destroyer from the 74th was positioned 200 yd from the bridge hull down behind a stone wall.

The Tiger came around a corner at 12 mph, turret still facing west toward the smoke. The tank destroyer fired twice. Both rounds hit the Tiger side armor at 200 yd. The first penetrated. The second detonated ammunition inside the hull. The Tiger erupted. The second Tiger in the village tried to withdraw north.

A P47 pilot tracked it from overhead, radioing its position to a second tank destroyer covering the northern road. The Tiger emerged from between two houses into a narrow lane. The tank destroyer fired from 300 yd. First round hit the front drive sprocket, immobilizing the Tiger. The crew bailed out. Infantry captured three of the four crew members within minutes.

Two Tigers engaged. Two Tigers destroyed or captured. Zero American tanks lost. Zero American fatalities. St. Obin Leatid became the template. Within 24 hours, every company in the regiment had received the new tactical procedures. Within 48 hours, the approach spread across the entire third army sector.

The results were staggering. In the 3 days before the village trap tactic was implemented, Tiger ambushes had destroyed 14 American tanks and killed 37 men. In the 3 days after American forces engaged and destroyed 19 Tigers while losing only five Shermans, the kill ratio had shifted from nearly 3:1 in the Tiger’s favor during the ambush phase to almost 4:1 in American favor.

News of the village trap spread through the Third Army like electricity. Tank crews who had been terrified of entering villages now actively sought Tiger contacts, knowing the system worked. Morale surged. Commanders who had resisted Patton’s aggressive approach saw the numbers and converted. Colonel Brennan, who had argued for halting the advance, quietly stopped sending reports to division recommending consolidation.

German commanders noticed the shift immediately. Bayerines afteraction reports from this period captured after the war revealed growing desperation. His dispersal tactic had worked for barely 48 hours before the Americans adapted. Tiger losses accelerated. Crews were increasingly reluctant to engage, knowing that firing their gun was essentially signing their own death warrant if they were inside a village.

Some crews abandoned their Tigers without firing at all, preferring capture to the near certainty of destruction. By September 18th, 5 days after the first engagement, 67 of the original 92 Tigers were destroyed, captured, abandoned, or immobilized. 25 remained nominally operational, but fuel shortages had reduced that number to perhaps 15 that could actually move and fight.

German high command’s iron hammer operation had not just failed, it had become a catastrophe. The strategic impact extended far beyond one regiment or one sector. Intelligence reports on Patton’s anti-tiger tactics were distributed to every Allied army in the European theater. British forces adopted modified versions within weeks.

The psychological effect on German armored forces was profound. Tiger crews who had entered battle believing themselves invulnerable now understood they were priority targets in a sophisticated killing system. German war production records show that by October 1944, requests from field commanders for Tiger replacements dropped sharply.

Not because Tigers weren’t needed, but because commanders had concluded that committing Tigers against Patton’s forces was simply feeding expensive machines into a destruction system. The resources were better spent on defensive fortifications and infantry weapons. The myth of the invincible tiger.

The weapon that had terrorized Allied armies since North Africa was dying in the fields and villages of Eastern France. Eddie Kowalsski received a bronze star for his role in the St. Auburn Lipy engagement. Major Whitfield was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Captain Hayes received a silver star for leading the company through four Tiger engagements without a single crew fatality.

Even Colonel Brennan, who had initially opposed everything, received a commendation for the regiment’s overall performance. But the war was not over. Far from it. The Tigers that remained were being pulled back toward the German border. And behind that border, something was being planned that would dwarf Operation Iron Hammer.

something that would throw a quarter million German soldiers and the last reserves of German armor against the Allies in a final desperate gamble. The date would become infamous, December 16th, 1944. The place, the Arden Forest, the Battle of the Bulge, and Eddie Kowalsski would be there in his Sherman with his notebook facing not 92 Tigers, but an entire German Panzer army.

But what happened to Eddie between September and December? The three months that military records barely mention contains a chapter that few people know. A chapter about a mechanic who became something more than a mechanic and a lesson about what happens when the man who helped win the battle becomes the man they blame when the next battle starts differently.

That story, the final chapter, is what part four is about. And it begins with a letter Eddie wrote home to Cleveland on November 3rd, 1944. a letter that his family kept secret for over 50 years. A former auto mechanic from Cleveland named Eddie Kowalsski wrote observations about Tiger Tank weaknesses in a small notebook.

That notebook helped reshape how Patton’s Third Army fought the most feared weapon in the German arsenal. In part one, Eddie’s insights reached Third Army headquarters and confirmed Patton’s own anti-tiger doctrine. In part two, those tactics shattered the first German defensive line, destroying 11 Tigers in 90 minutes.

In part three, when the Germans adapted by turning tigers into ambush predators hiding in villages, Patton’s forces adapted faster, creating a village trap system that turned every town into a killing ground for tigers. Of the 92 Tigers committed to Operation Iron Hammer, fewer than five survived the 72-hour battle. But the question that part three left unanswered is the one that matters most.

What happened to Eddie Kowalsski? What happened to the mechanic who helped kill the myth of the invincible tiger? The answer has a twist that nobody expected. Because success in war sometimes carries a price that no metal can repay. And Eddie’s price came due 3 months later in the frozen forests of the Arden.

The letter Eddie wrote home on November 3rd, 1944. The letter his family kept secret for over 50 years was addressed to his mother, Helen Kowalsski, at their house on East 71st Street in Cleveland. It was four pages long, written in pencil on US Army stationary, and it said things that Eddie had never told anyone in his unit.

He wrote about the men he had watched die. Not in tactical terms, not in the clinical language of afteraction reports. He wrote about the sound a man makes when he’s burning alive inside a Sherman tank. He wrote about Corporal James Dunning, his former loader, who had been killed at Montclair in a Tiger ambush.

He wrote about a French girl, maybe 10 years old, who had been killed by a stray 88 mm round that passed through a Sherman and into the house behind it. He wrote that he could not sleep without seeing their faces and that the only thing that kept him functioning was the work, the engines, the tanks, the mechanical problems that had logical solutions unlike the problems inside his head that had no solutions at all.

Eddie didn’t know the term. Nobody in 1944 did. But what Eddie was describing in that letter was what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. The mechanic who understood machines better than anyone in his regiment was discovering that the human machine was the one thing he couldn’t diagnose or repair. Despite this, Eddie kept fighting. His reputation had grown.

After the Tiger engagements in September 3rd, Army intelligence had formalized his observations into a technical bulletin distributed to every armored unit in the European theater. Eddie was promoted to sergeant. He was invited to brief new tank crews arriving as replacements on Tiger identification and weaknesses.

The mechanic from Cleveland had become an unofficial instructor in armored warfare. Lieutenant Colonel Whitfield, who had been promoted after the Tiger battles, kept Eddie close to the planning process. Whenever the regiment expected to encounter heavy German armor, Whitfield consulted Eddie about mechanical vulnerabilities, terrain assessment, and tactical positioning.

It was an extraordinary role for an enlisted man and it generated resentment among some officers who felt that a sergeant with no formal military education had no business influencing tactical decisions. Colonel Brennan, to his credit, had changed his opinion entirely. In a letter to division headquarters in October 1944, Brennan wrote that Sergeant Kowalsski possessed an intuitive understanding of armored combat that he had not encountered in 20 years of service.

He recommended Eddie for officer candidate school. Eddie declined. He told Morrison he wasn’t an officer. He was a mechanic. He just wanted to fix things that were broken. Then December came, the Arden, the Battle of the Bulge. On December 16th, 1944, a quarter million German soldiers with over 400 tanks and assault guns smashed through thinly held American lines in the forested hills of Belgium and Luxembourg.

Eddie’s regiment was rushed north to help contain the breakthrough. The conditions were nightmarish. Sub-zero temperatures, snow and ice that made roads impassible, fog that grounded Allied aircraft for days, eliminating the air support that had been so critical to the anti-tiger tactics. In September, Eddie’s Sherman threw a track on an icy road near Bastonia.

On December 22nd, while he was outside the tank in freezing darkness trying to repair the track, a German artillery barrage struck the road. Shrapnel from an air burst round hit Eddie in the left shoulder and back. Morrison dragged him behind the tank and applied field dressings until medics arrived. Eddie survived.

He was evacuated to a field hospital and then to England. He would spend 3 months recovering. The shrapnel in his back could not be fully removed. He was given a medical discharge in March 1945, 2 months before the war in Europe ended. He received the Purple Heart to add to his Bronze Star. He was 24 years old. He went home to Cleveland.

Eddie Kowalsski never returned to his uncle’s garage. The shoulder injury limited his range of motion, making it difficult to work under cars. He took a job as a quality inspector at a Ford plant in Brook Park, checking engines on the assembly line. It was steady work. It used his ear for machines that same instinct that had let him diagnose a tiger’s weaknesses by listening to its engine.

He married a woman named Patricia in 1947. They had three children. He never talked about the war. But his real legacy was not in Cleveland. It was in the doctrine manuals and war colleges of a dozen nations. And the influence of what Eddie and men like him contributed to armored warfare extended far beyond 1944.

The combined arms anti-armour tactics that Patton’s Third Army perfected against the Tigers in September 1944 became the foundation of American armored doctrine for the next eight decades. The principle was simple but revolutionary at the time. No single weapon system wins battles. Coordinated systems win battles.

A tank alone is vulnerable. A tank supported by artillery, air power infantry, and specialized anti-armour vehicles is part of a killing system that can defeat any individual weapon, no matter how powerful. This principle was codified in US Army Field Manual 1733, published in 1946, which explicitly referenced the Tiger engagements as case studies in combined arms operations against heavy armor.

The manual was updated for the Korean War where American forces used nearly identical tactics against North Korean T34 tanks, coordinating Persing tanks with artillery and close air support to achieve kill ratios that echoed the September 1944 battles. In Vietnam, the combined arms approach evolved to include helicopter gunships and precision artillery, but the underlying principle remained the same.

No single system fights alone. Everything coordinates. Everything attacks simultaneously. The enemy cannot respond to five threats at once. During the Gulf War in 1991, American M1 Abrams tanks faced Iraqi T72s in conditions remarkably similar to the open terrain of France in 1944. The Iraqis, like the German Tiger crews, had superior defensive positions and expected setpiece tank battles.

The Americans channeling Patton’s doctrine, used speed flanking maneuvers, air supremacy, and combined arms coordination to destroy over 3,000 Iraqi armored vehicles in 100 hours while losing fewer than 50 tanks. The kill ratio was almost incomprehensible and the tactical DNA could be traced directly back to the fields of Eastern France 50 years earlier.

NATO doctrine during the Cold War was built around the assumption that Soviet heavy armor would pour through the Fula Gap into West Germany in numbers that would dwarf the Tiger deployment of 1944. The response plan called Airland battle doctrine was essentially Patton’s five principles scaled up to a continental level.

Combined arms, multiple axes of attack, deep strikes against supply lines, relentless tempo, never let the enemy fight the battle they planned for. Over 40 nations adopted variations of this doctrine. Militarymies from West Point to Sandhurst to St. Seir taught the Tiger engagements as textbook examples of how tactics defeat technology. The total impact is impossible to quantify precisely, but military historians estimate that the combined arms revolution that crystallized in 1944 has influenced the training of over 12 million soldiers across the Western

Alliance in the eight decades since. The principles Eddie observed in his oil stained notebook became the grammar of modern armored warfare. But the biggest lesson from Eddie Kowalsski’s story is not about tanks or tactics or technology. It is about where good ideas come from. Eddie was a corporal, a mechanic.

He had no military academy education, no training in tactical doctrine, no credentials that anyone in the chain of command would have recognized as qualifying him to comment on armored warfare strategy. He was by every institutional measure the last person who should have been contributing to how a regiment fought Tiger tanks. And yet his observations were right.

Not because he was a genius, because he was a mechanic. He looked at the Tiger the way he looked at a Chevrolet with a bad transmission. He didn’t see a legendary super weapon. He saw a machine. And every machine has specs, tolerances, failure modes, and breaking points. The experts in the room. The West Point graduates, the career officers.

They saw doctrine and history and strategy. Eddie saw a machine with a turret that took 60 seconds to rotate and an engine that drank fuel like a man dying of thirst. This pattern repeats across every war and every era of innovation. The people closest to the problem often see solutions that the experts miss because experts are trained to see problems through the lens of existing doctrine and doctrine is just yesterday’s innovation hardened into dogma.

The British sailor who figured out that citrus fruit prevented scurvy was ignored for decades by naval surgeons who knew better. The Wright brothers were bicycle mechanics who were told by the most credentialed physicists of their era that powered flight was impossible. Percy Spencer, the engineer who invented the microwave oven, had no college degree.

He noticed that a candy bar in his pocket melted near a magnetron and asked why. In modern warfare, this lesson has become explicit policy. The US military’s rapid innovation fund specifically solicits ideas from junior enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers, the modern equivalents of Eddie Kowalsski. The Israeli Defense Forces are famous for their flat command culture where a private can challenge a general’s tactical decision in real time.

These aren’t just cultural preferences. They are institutional acknowledgements that the person closest to the problem, the mechanic under the tank, the driver behind the controls, sometimes sees what the general behind the map cannot. In the business world, the same principle drives every startup that disrupts an established industry.

The founders of Airbnb were design students, not hotel executives. The creators of Spotify were music fans, not record label presidents. Innovation doesn’t come from credentials. It comes from proximity to the problem and the courage to say what you see, even when everyone with more rank and more experience tells you you’re wrong.

And there is one final detail about Eddie Kowalsski’s story that almost no one knows. In 1998, a military historian named Dr. Robert Callahan was researching Third Army after action reports at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. He found something unexpected in a box of declassified documents from the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

It was a single page typewritten dated October 1944. It was a recommendation from Lieutenant Colonel Whitfield to Third Army Intelligence proposing that the anti-tiger tactical procedures developed during Operation Iron Hammer be formalized and attributed to their original source. Whitfield’s recommendation included a name, not his own, not Captain Hayes, not Colonel Brennan.

The name on the document was Corporal Edward J. Kowalsski, US Army, and the document recommended that the tactical bulletin be officially designated the Kowalsski protocols. The recommendation was denied. Third Army staff decided that attributing tactical doctrine to an enlisted mechanic would undermine the authority of commissioned officers.

The bulletin was published anonymously as technical bulletin 4417. Eddie’s name appeared nowhere in it. The most influential piece of anti-armour tactical guidance produced by the American military in World War II was written by a corporal from Cleveland and for over 50 years nobody outside his regiment knew it. Dr. Callahan tracked down Eddie’s family.

Eddie had died in 1991 at the age of 70 in the same house on East 71st Street where his mother had received that letter in November 1944. Patricia had died 2 years before him. His children, two daughters and a son, had no idea about the document. They knew their father had served in Patton’s Third Army.

They knew about the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart. They knew he never talked about the war. They did not know that their father’s observations had helped reshape how the United States Military Fights armored battles to this day. In 2003, the Association of the United States Army published Dr. Callahan’s research.

For the first time, the name Edward Kowalsski was publicly connected to the anti-tiger tactics of September 1944. A small ceremony was held at the Army Heritage Center in Carile, Pennsylvania. Eddie’s son, Thomas Kowalsski, accepted a postumous commendation on behalf of his father. Thomas later told a reporter that his father would have been embarrassed by the attention.

Dad always said he was just a mechanic who got lucky. Thomas said he never thought he did anything special. He just looked at the tiger and saw what was broken. From a Chevrolet mechanic with an oil stained notebook to a tactical revolution that influenced 80 years of armored warfare across 40 nations. Eddie Kowalsski proved that the most dangerous weapon in any army is not the biggest tank or the most powerful gun.

It is the person who looks at an impossible problem and sees it differently than everyone else. 92 Tiger tanks were sent to stop Patton. Fewer than five survived. Not because the Sherman was better. Not because the Americans had more money or more factories, though they did. They were destroyed because a mechanic who had never read a tactical manual understood something that generals with decades of experience had missed.

Every machine breaks. Every weapon has limits. And the side that finds those limits first wins the war. Eddie Kowalsski fixed Chevrolets. Then he fixed how America fights. He never knew the full extent of what he accomplished. And that might be the most important lesson of all. The people who change history rarely know they’re doing it.

They’re just solving the problem in front of them with whatever tools they have, the best way they know how. If you know a story like Eddie’s, a person who saw something nobody else saw and changed everything, share it in the comments. History is full of mechanics and farmers and teachers who did impossible things because nobody told them it was impossible in time.

Subscribe so you don’t miss the next one. Because the greatest stories from the Second World War aren’t about generals and presidents. They’re about the people whose names were almost lost. The people who won the war, one observation, one notebook, one crazy idea at a time. The Tigers are gone. The Shermans are in museums.

But somewhere right now there’s another mechanic looking at an impossible problem and seeing what everyone else has missed. That’s how wars are won. That’s how the world changes. And that is why this story was worth telling.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.