“I’m Infected” – A 18-Year-Old German POW Boy Arrived With 9 Shrapnel Wounds – Exam SHOCKED Everyone. NU

“I’m Infected” – A 18-Year-Old German POW Boy Arrived With 9 Shrapnel Wounds – Exam SHOCKED Everyone

The boy stands in the examination room at Camp McCain in Mississippi, shirtless and shaking, and says the words in broken English before the doctor even touches him. I am infected. His voice is flat, matterof fact, as if he is reporting the weather. The camp doctor, Major William Brennan, steps closer and sees what the intake officer missed in the processing line.

The boy’s torso is covered in wounds. Nine separate puncture sites scattered across his chest, abdomen, and back like someone threw gravel at him from different directions. Some of the wounds are scabbed over. Some are still weeping. One on his left side, just below the ribs, is ringed with red streaks that climb toward his armpit like vines.

The smell hits the doctor next, the unmistakable rot of deep infection. Major Brennan looks at the boy’s face and sees something that disturbs him more than the wounds. The boy is not afraid. He is resigned. He has been waiting to die for so long that arrival at an American prison camp feels like nothing more than a change of location.

We are at Camp McCain, Mississippi in late April 1945. The camp holds over 3,000 German prisoners of war. Most of them captured in North Africa or Italy and shipped to the American South for internment. The camp is surrounded by pine trees and farmland far from any major city, far from the war.

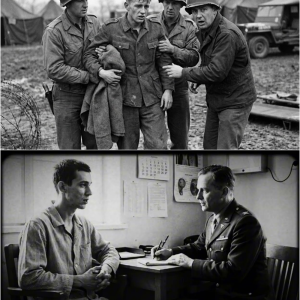

The prisoners work in cotton fields and lumber mills, guarded by American soldiers who are too old or too injured to fight overseas. It is not a harsh camp by prisoner of war standards. The food is adequate. The barracks are clean. Men survive here. But today, a transport truck arrives with 20 new prisoners from a processing center in Virginia.

And one of them is different. His name is listed on the intake paperwork as Klaus Hoffman, 18 years old, captured by American forces near the Elba River in central Germany 2 weeks earlier. He is small for 18, barely 5′ 6 in tall, and so thin that his uniform hangs on him like a tarp over a fence post. His face is covered in dirt, and his eyes are hollowed out from lack of sleep.

When the intake officer tells him to remove his jacket for the standard lice check, Klouse hesitates. Then he peels off the jacket slowly and the officer sees the stains on his undershirt, brown and yellow, spreading out from multiple points on his torso. The officer calls for the camp medic immediately. The medic, a corporal from Tennessee, takes one look at Klouse and sends him straight to the camp hospital without even completing the intake process.

Klouse does not protest. He walks to the hospital building with his jacket draped over one arm, his steps slow and deliberate, like a man walking to his own execution. The medic follows behind, noting the way Klouse holds his left arm slightly away from his body, the way he winces when he breathes too deeply.

This is not a healthy prisoner. This is a boy who should already be dead. We are now inside the camp hospital examination room. A small whitewashed space with a metal table, a cabinet of supplies, and a single overhead light. Major William Brennan, the camp doctor, is a general practitioner from Atlanta who volunteered for military service in 1942 and was assigned to prisoner of war medical duty after 2 years in field hospitals in Europe.

He has seen thousands of wounded men. He has seen shrapnel injuries, bullet wounds, burns, frostbite, and every disease that thrives in wartime conditions. But when Klaus Hoffman walks into his examination room and says those three words, “I am infected,” Brennan knows immediately that this case is not routine.

Brennan tells Klouse to sit on the examination table and remove his shirt. Klouse does so without hesitation, lifting the stained undershirt over his head and dropping it on the floor. What Brennan sees makes him pause. Klaus’s torso is a map of violence. There are nine separate wounds, each one a puncture or laceration caused by shrapnel or shell fragments.

Three wounds are on the chest, four are on the abdomen, two are on the back. The wounds are in different stages of healing. Some are old scars, white and puckered. Some are partially healed, covered with fresh scabs. Some are still open, the edges red and inflamed, the centers filled with yellowish discharge. Brennan pulls on gloves and begins to examine each wound systematically.

Starting with the oldest scars and working his way to the freshest injuries, he notes the locations on a chart, sketching Klaus’s torso and marking each wound with a number. The first three wounds, all on the upper chest, are healed, but badly scarred. The tissue is thick and riged, suggesting they healed without proper medical care.

The next four wounds, clustered around the abdomen, are in various stages of infection. Two are scabbed over, but oozing pus. Two are open and raw, the flesh around them swollen and hot to the touch. The final two wounds, one on the lower back and one just below the left ribs, are the worst. The wound on the back is a deep crater, as if someone scooped out a chunk of flesh.

The wound below the ribs is surrounded by red streaks, the telltale sign of blood poisoning spreading through the lymphatic system. Brennan steps back and asks Klaus how he got these wounds. Klouse answers in heavily accented English, his words slow and careful. Different times, different places. Brennan asks him to explain. Klaus takes a breath, winces, and begins to talk.

The first three wounds came from an artillery shell in France in August 1944. The next four came from a grenade in Belgium in December 1944. The last two came from machine gun fire near the Elba River in April 1945, 3 days before he was captured. Brennan writes this down, then looks at Klouse in disbelief. You were wounded three separate times, and you were sent back to fight each time. Klouse nods.

He says, “There were no hospitals. There were no doctors. There were only bandages and orders to return to the line. If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel. We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered.

We are still in the examination room and Major Brennan is trying to process what Klouse has just told him. Three separate wounding events over 9 months. nine pieces of shrapnel or shell fragments still lodged in the boy’s body and no proper medical treatment for any of them. Brennan asks Klouse if he still has the shrapnel inside him. Klouse nods again.

Brennan orders an X-ray immediately. The camp has a portable X-ray machine, old and temperamental, but functional. A medic brings Klouse to the radiography room and positions him carefully taking images of his chest, abdomen, and back. 20 minutes later, Brennan is standing in front of the light box, staring at the X-ray films with a nurse beside him.

What he sees confirms Klaus’s story and reveals something even more disturbing. The X-rays show nine separate pieces of metal embedded in Klaus’s body, scattered through muscle tissue, lodged against ribs, pressing against organs. But the shocking part is not the number of fragments.

The shocking part is the variety. The shrapnel pieces are different sizes, different shapes, and based on their positions and the surrounding tissue damage. They entered the body at different times and from different directions. The three fragments in the upper chest are small and symmetrical, consistent with artillery shrapnel.

The surrounding bone shows signs of old fractures that healed improperly. The four fragments in the abdomen are irregular and jagged, consistent with grenade fragments. One of them is dangerously close to the liver. Another is pressing against the lower edge of the stomach. The tissue around these fragments shows chronic inflammation, meaning they have been causing damage for months.

The two fragments near the back and the ribs are the largest and the most recent. One is a twisted piece of metal lodged in the muscle of the lower back. The other, the one below the ribs surrounded by infection, is a bullet fragment that has created an abscess, a pocket of pus and dead tissue that is slowly poisoning Klaus’s bloodstream.

Brennan turns to the nurse and asks her to call the camp commander. This is not just a medical case. This is evidence of something that violates every standard of military conduct. Klaus Hoffman is 18 years old. That means he was 16 when he received the first set of wounds. He was a child sent into combat wounded and sent back without treatment.

Wounded again, sent back again. wounded a third time and only captured because he physically could not run anymore. Brennan has treated hundreds of German prisoners, but he has never seen a case like this. This is not a soldier who was unlucky. This is a boy who was used until he broke. We are now 30 minutes after the X-rays and Major Brennan is sitting across from Klouse in a small office attached to the hospital.

Brennan has sent the X-ray films to the camp commander, but before he treats Klouse, he needs to understand the full story. Klouse sits in a wooden chair, his shirt back on, his hands resting in his lap. Brennan asks him to start from the beginning. How did you end up in the German military at 16 years old? Klouse speaks slowly, his English improving as he relaxes slightly.

He says he grew up in a small town near Dresdon in Eastern Germany. His father worked in a factory. His mother died when he was 12. He had one older brother who was conscripted into the Vermacht in 1942 and killed on the Eastern Front in 1943. When Klouse turned 16 in July 1944, he received a letter ordering him to report for military service.

Germany was losing the war by then. The casualty rates were catastrophic. The military was conscripting anyone who could hold a rifle, including boys who should have been in school. Klouse was sent to a training camp for 2 weeks, given a uniform and a rifle, and assigned to an infantry unit defending the French coast near Khan.

He arrived just as the Allied breakout from Normandy was beginning. Within 3 days, his unit was under constant artillery bombardment. That is when he received the first three wounds. An artillery shell landed 10 m from his position and he was thrown backward by the blast. When he woke up, his chest was bleeding from three separate puncture wounds.

A medic pulled the largest pieces of shrapnel out with forceps, wrapped the wounds with gauze, and told him to rejoin his squad. There was no hospital. There was no evacuation. The unit was retreating and anyone who could walk was expected to keep fighting. Klouse fought through August and September as the German army retreated across France and into Belgium.

By October, the wounds on his chest had scabbed over, but they hurt constantly. He could not lift his rifle above his shoulders without pain. In December, his unit was caught in the Battle of the Bulge, Germany’s last major offensive in the West. During a counterattack near Bostonia, a grenade exploded inside the building where Klaus and five other soldiers were sheltering.

Klouse was knocked unconscious. When he woke, he had four new wounds in his abdomen, and two of the other soldiers were dead. This time, there was not even a medic. Klouse wrapped his own wounds with strips torn from a dead man’s shirt and kept moving. The offensive collapsed. The retreat continued and Klaus, now 17 years old, kept fighting because stopping meant being shot for desertion.

Let us know in the comments where you are watching this from. Are you in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, or somewhere else? We would love to know who is keeping these stories alive. Brennan listens to this story with growing horror, writing down every detail. He asks Klaus about the final two wounds.

Klaus says those came in the last days of the war in midappril 1945. His unit was near the Elba River trying to retreat west toward the American lines to avoid being captured by the Soviets. They were caught in a crossfire between American and German forces. The machine gun fire came from behind them from German troops who were firing on anyone trying to surrender.

Klaus was hit twice, once in the back and once below the ribs. He fell into a ditch and lay there for 6 hours until American soldiers found him. By then he was too weak to stand. He was bleeding, feverish, and delirious. The Americans put him on a truck with other prisoners and sent him through the processing chain that eventually brought him to Camp McCain.

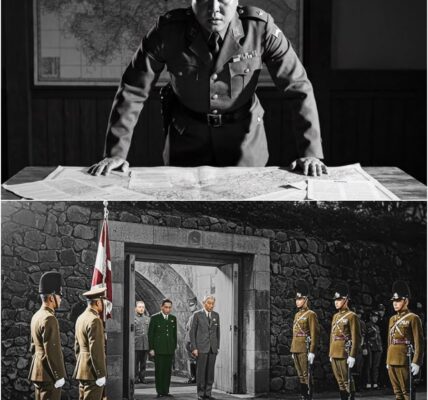

We are now 1 hour after Klaus’s arrival at the camp hospital and Major Brennan is in the camp commander’s office explaining why this case is extraordinary. The commander, Colonel James Harrington, is a career officer from Virginia who has been running Camp McCain since 1943. He has dealt with thousands of German prisoners and he prides himself on running a camp that follows the Geneva Conventions to the letter.

But Klaus Hoffman’s case is different. Harrington looks at the X-ray film spread across his desk and listens as Brennan explains the timeline. Three wounding events, nine pieces of shrapnel, no treatment, a 16-year-old conscript used as cannon fodder until he could not fight anymore. Harrington asks the question that matters most.

Can you save him? Brennan admits he does not know. The infection below the ribs is spreading. If it reaches the bloodstream completely, Klaus will go into septic shock and die. The only way to stop the infection is to remove the shrapnel fragments and clean out the abscesses. But that means major surgery, possibly multiple surgeries.

and Klaus is already weak from months of malnutrition and blood loss. Brennan estimates Klaus has a 50% chance of surviving the surgery and a 70% chance of dying within the next week if they do nothing. Harington considers this, then gives his approval. He tells Brennan to proceed with the surgery and to document everything.

If Klaus survives, his story will be part of the war crimes documentation being compiled by Allied intelligence. Brennan returns to the hospital and tells Klouse what is going to happen. The surgery will be extensive. They will have to open multiple sites on his torso to remove the shrapnel and clean out the infections.

Klouse will be under general anesthesia and the recovery will take weeks, possibly months. There is a significant risk that he will not survive. Klaus listens without expression. Then he asks a question that surprises Brennan. If I die during the surgery, will you write to my family? Brennan asks if Klaus has family left in Germany. Klaus says he does not know.

He lost contact with his father in January. The town where he grew up was bombed in February. He has no idea if his father is alive or if the house is still standing. But if Brennan can find them, Klouse wants them to know he did not die in combat. He wants them to know he died in a hospital with a doctor trying to help him.

We are now in the camp hospital operating room, a converted barracks room with surgical lights, a table and equipment borrowed from the nearest civilian hospital. The surgery is scheduled for the following morning, April 24th, 1945. Brennan has recruited a second doctor from the civilian hospital in nearby Grenada along with two experienced surgical nurses.

Klaus is brought in at 7 in the morning, his torso marked with ink to show the locations of the nine shrapnel fragments. He is given a general anesthetic and within minutes he is unconscious on the table. Brennan makes the first incision over the wound below the ribs, the one with the spreading infection. the skin parts and immediately the smell of rot fills the room.

Underneath the skin, the tissue is gray and black, soaked with pus. Brennan uses forceps and a scalpel to cut away the dead tissue, a process called debrement. He removes nearly half a pound of infected muscle before he reaches the source of the problem. The bullet fragment is lodged against a rib, and the impact created a pocket where bacteria have been growing for weeks.

Brennan extracts the fragment carefully, a twisted piece of copper jacketed steel about the size of a dime, and drops it into a metal tray. The surgery continues for 5 hours. Brennan and the assisting doctor work methodically through each wound, opening the old scars, removing the embedded shrapnel, cleaning out the infections, and stitching the tissue back together.

They remove all nine fragments along with nearly 2 lbs of dead and infected tissue. The fragments are placed in a tray for documentation. Some are sharp and clean like pieces of a broken blade. Others are rough and corroded, stained with rust and blood. The largest fragment from Klaus’s back is the size of a quarter and has a jagged edge that sliced through muscle like a saw.

If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel. We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered. When the surgery is finally finished, Klouse’s torso is covered in fresh stitches and bandages. He has lost nearly a pint of blood during the procedure and his vital signs are weak.

Brennan orders him moved to the intensive care section of the hospital. a small room with four beds where the sickest patients are monitored around the clock. The nurses set up intravenous lines to give Klouse fluids and blood plasma. For the next 24 hours, Klaus’s survival is uncertain. His fever climbs. His breathing becomes shallow.

Twice, Brennan is called to the bedside because Klaus’s heart rate drops dangerously low. But on the second night after the surgery, the fever breaks. Klaus’s breathing stabilizes. On the third morning, he opens his eyes. We are now 5 days after the surgery and Klouse is conscious and talking. He is still weak, still in pain, but the infection is gone. His temperature is normal.

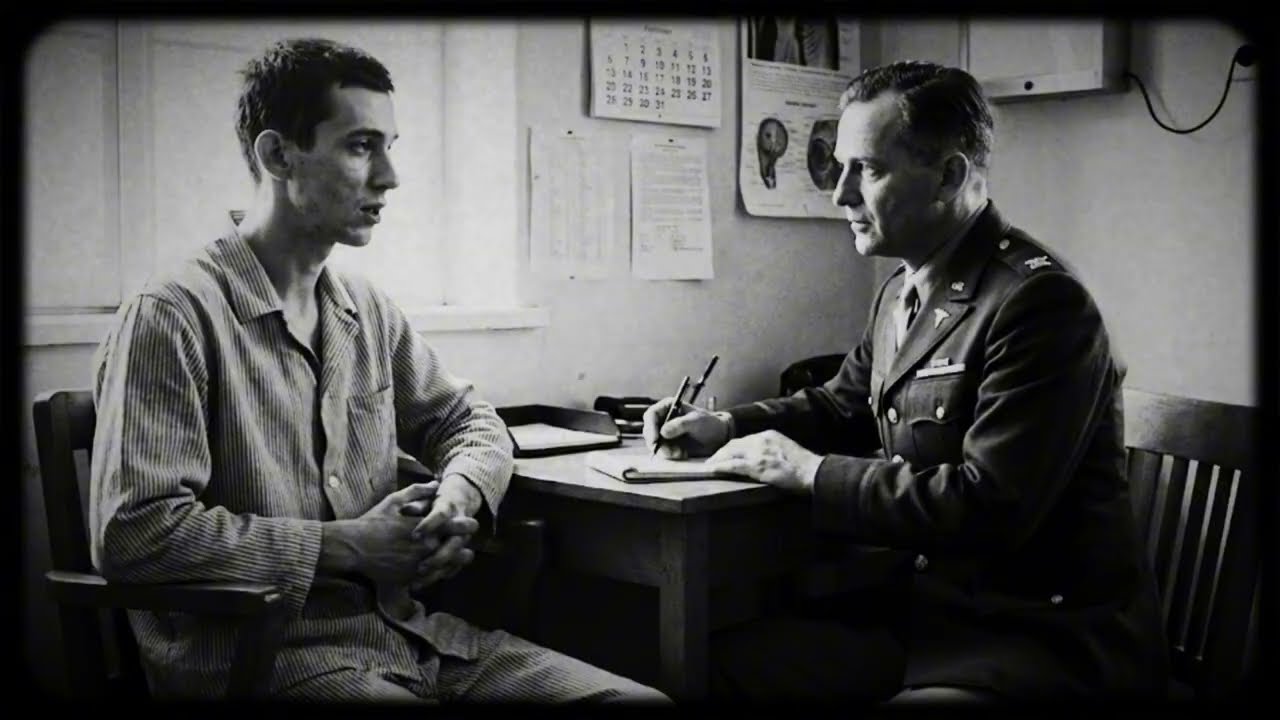

The wounds are healing cleanly. Major Brennan visits him twice a day to check the stitches and change the bandages. On the sixth day, Brennan brings a visitor. His name is Captain Leonard Moss, an intelligence officer assigned to Camp McCain to interview prisoners and compile reports for the war department. Moss has heard about Klaus’s case and wants to take a formal statement.

Klouse agrees to the interview. He is propped up in bed, his torso wrapped in bandages, an intravenous line still running into his arm. Moss sits beside the bed with a notepad and a translator, though Klouse insists he can speak English well enough. Moss asks Klouse to repeat his story, starting from his conscription in July 1944.

Klouse does so, adding details he did not tell Brennan. He describes the training camp where boys as young as 15 were given uniforms and rifles and told they were the future of Germany. He describes the retreat across France, the constant bombardment, the officers who shot deserters on site. He describes the hunger, the cold, the nights spent in bombed out buildings with no heat and no food.

Moss asks Klaus about the decision to send wounded soldiers back into combat without treatment. Klouse explains that by late 1944, Germany had lost most of its medical infrastructure. Hospitals were being bombed. Doctors were being conscripted into combat units. Field medics had no supplies. If you were wounded and you could still walk, you were sent back to the line.

If you could not walk, you were left behind. Klaus says he saw boys younger than him bleed to death from wounds that could have been treated with basic first aid simply because there was no one to treat them. He says the officers did not care. They knew the war was lost. They were just trying to delay the collapse as long as possible.

And boys like Klouse were ammunition to be expended. Moss asks Klouse about the final wounds, the ones from German machine gunfire. Klouse confirms what Brennan suspected. In the last days of the war, German units were ordered to shoot anyone attempting to surrender to the Americans. The officers feared that mass surrenders would trigger a complete collapse of the defense, so they set up machine gun positions behind their own lines and fired on anyone trying to cross to the American side.

Klouse says he was in a group of about 30 soldiers who decided to surrender together. They walked toward the American lines with their hands up. The German machine guns opened fire from behind. Half the group was killed. Klouse was hit twice but kept running. He made it to a ditch on the American side and passed out.

When he woke, he was a prisoner and for the first time in 9 months, no one was shooting at him. We are now 2 weeks after the surgery and Klaus is recovering steadily. He can sit up in bed without help. He can eat solid food. The stitches are starting to dissolve and the wounds are closing, but the psychological scars are deeper than the physical ones.

The nurses notice that Klouse does not sleep well. He wakes up several times each night, gasping and staring at the ceiling. He refuses to talk about his dreams. Major Brennan recognizes the signs. Klouse is suffering from what military doctors call battle fatigue, what later generations will call post-traumatic stress disorder.

Brennan arranges for Klaus to speak with a psychiatrist, a captain named David Rubin, who visits Camp McCain once a week to evaluate prisoners with mental health issues. Reuben spends 2 hours with Klouse asking questions about his experiences, his feelings, his plans for the future. Klouse is guarded at first, but eventually he opens up.

He tells Reuben that he does not feel like a soldier. He never wanted to fight. He was ordered to fight and he obeyed because the alternative was execution. He tells Reuben that he killed men during the war, but he does not know how many or even if they were enemies. In the chaos of the retreat, everyone was shooting at everyone.

He tells Reuben that he feels guilty for surviving when so many others died. He says he does not understand why the American doctors worked so hard to save him. He says he is not worth saving. Rubin writes a detailed report on Klaus’s mental state, concluding that the boy is suffering from severe trauma and will require long-term psychiatric care.

Reuben notes that Klaus exhibits signs of survivors guilt, depression, and dissociation. He recommends that Klouse be transferred to a hospital facility that can provide both medical and psychological treatment. But Ruben also notes something else in his report. Despite the trauma, despite the guilt, Klaus has not lost his humanity. He is polite to the nurses.

He thanks the doctors. He asks about the other patients in the ward. Reuben writes that Klaus Hoffman is proof that even the most brutal experiences cannot completely destroy a person’s capacity for decency if that capacity was there to begin with. We are now 3 weeks after the surgery and Major Brennan is compiling a final report on Klaus’s case for submission to the War Department.

As he reviews the medical records, he realizes that Klaus’s story is part of a much larger and darker pattern. By the spring of 1945, the German military was conscripting boys as young as 14 and men as old as 60. The Vulderm, the last ditch militia, was filled with children and elderly civilians who had never received military training.

Casualty rates among these units were catastrophic. In some battles, entire Vulkerm battalions were wiped out within hours. Brennan notes in his report that Klouse was conscripted at 16, which means he falls into a category that the Geneva Conventions define as a child soldier. The use of child soldiers is considered a war crime.

But by 1945, Germany was no longer following any international laws. The numbers tell the story. Between January and May 1945, an estimated 100,000 boys under the age of 18 were conscripted into the German military. Of those, roughly 40,000 were killed in combat. Another 30,000 were wounded. many of them multiple times.

The remaining 30,000 were captured or deserted. Klouse was one of the lucky ones, if luck is the right word, for a boy who spent 9 months being shot at and ended up with nine pieces of metal in his body. The report also includes data on medical care in the final year of the war.

By mid 1944, the German medical system was collapsing. Hospitals were overcrowded. Supplies were running out. Doctors were being conscripted. Wounded soldiers were being sent back to combat with minimal treatment. Not because commanders were cruel, but because there was no alternative. The system had broken down completely. Brennan estimates that thousands of German soldiers died from wounds that would have been survivable with proper medical care.

Klaus’s survival for 9 months with untreated shrapnel wounds and chronic infections is statistically improbable. Most men in his condition would have died from sepsis within weeks. The fact that Klouse lived long enough to be captured and treated is either extraordinary luck or extraordinary physical resilience. Brennan suspects it is both.

We are now 6 weeks after the surgery and Klouse is well enough to be discharged from the camp hospital. But the question remains, where does he go? Standard procedure is to transfer recovered prisoners to the general population barracks where they live and work alongside other prisoners. But Klouse is not a standard case. He is still recovering physically and he needs ongoing psychiatric care.

Major Brennan recommends that Klaus be transferred to a specialized facility for prisoners who require long-term medical treatment. Colonel Harrington agrees. In late May 1945, Klouse is transferred to a hospital camp in Texas, a facility that houses German prisoners with chronic medical conditions or disabilities.

The camp is smaller than McCain, holding only about 200 prisoners, and it has a full medical staff, including surgeons, psychiatrists, and physical therapists. Klouse will spend the next 6 months there undergoing physical rehabilitation to rebuild the muscle tissue damaged by the shrapnel wounds and psychiatric counseling to address the trauma.

The doctors in Texas continue the work that Brennan started, monitoring Klouse’s wounds, watching for signs of infection, and helping him regain his strength. Klouse adjusts slowly to life at the hospital camp. He participates in physical therapy sessions, learning to move without pain for the first time in months.

He attends group counseling sessions with other young prisoners, many of whom have similar stories of being conscripted as teenagers and traumatized by the war. Slowly, Klouse begins to talk about his experiences more openly. He writes letters to the International Red Cross, asking them to search for his father in Germany. He asks the camp librarian for books in German, and he reads obsessively, trying to fill the gaps in his education.

He was 16 when he was conscripted. He never finished school. Now at 18, he is trying to catch up on everything he missed. We are now moving forward into the uncertain months after the war ended in Europe. Germany has surrendered. The camps are full of prisoners waiting to be repatriated.

But Klaus’s situation is complicated. He is medically fragile, still recovering from surgeries and infections. sending him back to Germany in his condition is risky. Moreover, Germany itself is in chaos. Cities are destroyed. The economy has collapsed. Food is scarce. The Allied occupation authorities are overwhelmed trying to manage millions of displaced persons.

Klouse has nowhere to go. His hometown was heavily bombed. His father has not responded to Red Cross inquiries. Klouse is functionally an orphan. The decision is made to keep Klouse in the United States until he is fully recovered and until conditions in Germany stabilize enough for safe repatriation.

This means Klaus will spend at least another year, possibly longer, in American custody. He is transferred back to Camp McCain in early 1946, not as a hospital patient, but as a general population prisoner. He is assigned to a work detail on a nearby farm, light labor that will not strain his healing wounds.

He works in the fields planting cotton, living in the barracks with other German prisoners, eating in the mess hall, attending occasional education classes taught by volunteers from the local community. Klouse adapts to this new life with the same quiet resilience he showed throughout the war. He does not complain. He does not cause trouble.

He works. He reads, he waits. The other prisoners are wary of him at first. His story has spread through the camp, and some of the older prisoners resent the fact that Klouse received extensive medical care, while others were left to recover on their own. But Klouse ignores the resentment.

He keeps to himself, focuses on his work, and slowly earns a reputation as someone reliable. The guards like him. The farm supervisors like him. The camp administrators note in his file that Klaus Hoffman is a model prisoner, cooperative and hardworking. We are now stepping back to consider the broader implications of Klaus’s story.

By the end of World War II, the Allied powers were beginning the process of prosecuting war crimes. The Nuremberg trials were underway and thousands of German military and political leaders were being investigated for atrocities. But Klaus’s case raises a different question. Is a 16-year-old conscript who was forced to fight under threat of execution a war criminal, or is he a victim? The Geneva Conventions are clear that prisoners of war cannot be prosecuted simply for fighting as long as they followed the laws of war. But the conventions also

recognize that certain actions like the use of child soldiers are war crimes. Klouse was a child soldier, but he was not the one who made the decision to conscript children. He was the one who suffered because of that decision. Military lawyers reviewing Klaus’s case conclude that he committed no war crimes.

He was a victim of war crimes committed by his own government. This distinction is important. It means Klouse will be repatriated eventually, not prosecuted. But the question of justice is not just legal. It is moral. Klouse spent two years of his adolescence in constant danger, wounded three times, denied medical care, and nearly killed by his own side when he tried to surrender.

Who is responsible for that? The officers who sent him back to fight. The system that conscripted children. the leaders who prolonged a war they knew was lost. Klouse does not have answers to these questions. He tells the psychiatrist in Texas that he does not think about justice anymore. He thinks about survival.

He thinks about building a life after the war if he can. He thinks about forgetting even though he knows he never will. We are now in the final section of this story, reflecting on what Klaus Hoffman’s experience teaches us about the cost of war and the limits of human endurance. The first lesson is that war consumes the young first.

Klaus was conscripted at 16, an age when most boys are still in school, still figuring out who they are. Instead of an education and a childhood, Klouse got a rifle and a battlefield. He was wounded, sent back to fight, wounded again, sent back again until his body could not take anymore. His story is not unique. Tens of thousands of boys his age were fed into the war machine in the final year of the conflict. Most of them did not survive.

Klaus did, but the cost was nine pieces of metal in his body and scars that will never fully heal. The second lesson is that medical care is a form of moral accounting. Major Brennan had no obligation to save Klouse beyond the basic requirements of the Geneva Conventions. He could have treated the wounds superficially and moved on.

Instead, he performed 5 hours of surgery, removed infected tissue, and fought to keep Klouse alive because he believed it was the right thing to do. That decision gave Klouse a future. Without it, Klouse would have died in a prison camp in Mississippi, another casualty in a war that ended months before.

Brennan understood something fundamental, that treating a patient is not just about the body. It is about affirming that the person’s life has value. Klaus was a German soldier, but he was also a boy who deserved a chance to grow

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.