Your Wound Is Rotting…” — German POW Broke Down When American Doctor Cleaned His Leg Injury. NU

Your Wound Is Rotting…” — German POW Broke Down When American Doctor Cleaned His Leg Injury

The smell hits the American doctor before he even enters the room. It is not just dirt or sweat. It is rot, sweet, thick, unmistakable. The kind of smell that tells you infection has already won most of the battle. He pushes the door open and sees a German prisoner of war lying on a cot, pale, shaking, eyes locked on the ceiling like he is already somewhere else.

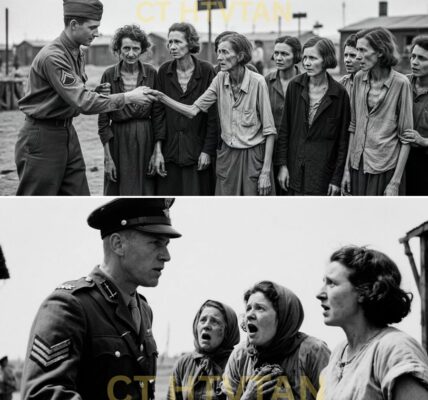

The guard at the door mutters something about wasting medicine on the enemy, but the doctor is not listening. He walks closer, pulls back the blanket covering the prisoner’s left leg, and freezes. The wound is open, oozing, edges black and green. The prisoner turns his head just enough to meet the doctor’s eyes, and for the first time in weeks, he does something he thought he would never do again. He cries.

The facility is a prisoner of war hospitals somewhere in the American Midwest. Late spring of 1945, Germany is collapsing, but the evidence of its final thrashing keeps arriving in trucks, trains, and cattle cars. Some prisoners are combat wounded. Others are sick from camps, forced marches, starvation diets, and neglect.

This one came in yesterday with a transport group from a temporary holding area near the East Coast. His name is Walter. He is 19 years old. When the intake nurse asked him how long the leg wound had been open, he said he did not remember anymore. The nurse wrote infection severe on the intake form and moved him to isolation.

That night, Walter did not sleep. He lay on the cot staring at the ceiling expecting nothing. He had been a prisoner for 3 months. Before that he was infantry in the Vermacht fighting in France during the last desperate winter before the collapse. He took shrapnel in the left calf during an Allied artillery barrage near the Seief freed line.

The field medic wrapped it with dirty gauze and told him to keep moving. There was no time for proper treatment. The line was falling apart. A week later, Walter was captured by American forces pushing east. At first, the wound seemed manageable. It hurt, but so did everything else. Hunger, cold, exhaustion, fear.

He did not think about infection until the pain changed. It stopped being sharp and became deep, pulsing, constant. The skin around the wound turned dark. Fluid began seeping through the bandage. Other prisoners in the transport truck noticed the smell and moved away from him. One older prisoner, a sergeant, leaned over and whispered that he should ask for a doctor when they reached the camp.

Walter nodded but did not believe anything would happen. He had heard stories about what happened to wounded prisoners. Some were treated, some were left to rot. He did not know which category he would fall into. When the American guards unloaded the transport truck at the temporary holding facility, Walter could barely walk.

A guard noticed him limping and dragged him to a processing tent. A medical officer took one look at the leg, said something in English Walter did not understand, and waved for two other men to carry him to a vehicle. Walter thought they were taking him somewhere to die quietly. Instead, they brought him here to this hospital, to this room, to this moment when an American doctor pulls back the blanket and does not look away.

The doctor’s name is Captain Richard Lawson. He is 34 years old, trained in surgery at a hospital in Pennsylvania, deployed to Europe in 1943, and rotated back to the States 6 months ago to work in prisoner of war medical facilities. He has seen infected wounds before, plenty of them, but this one is worse than most.

The original shrapnel entry is about 3 in long, running down the outer calf. The edges are necrotic, which means the tissue is dead and turning black. The surrounding skin is swollen, red, hot to the touch. There is pus, but also something worse. A grayish film covers part of the wound. Lawson recognizes it immediately. Gas gang green.

If left untreated, it will kill Walter within days, maybe hours. Lawson calls over a nurse, a young woman named Lieutenant Sarah Brennan, and tells her to prepare for deb breedment. That means cutting away all the dead tissue to stop the infection from spreading. Brennan glances at Walter, then back at Lawson and asks if they should sedate him first. Lawson shakes his head.

There is not enough time to wait for anesthesia to take full effect, and they are low on supplies. The surgery will have to happen now with only local numbing agents and whatever pain tolerance Walter has left. Brennan hesitates then nods. She has done this before. It is never easy. Walter watches them move around the room gathering instruments, bottles, clean gauze, metal trays.

He does not understand the words, but he understands the tone. Something is about to happen and it is going to hurt. Lawson approaches the bed and tries to explain in broken German that they are going to clean the wound. Walter hears the word schnaden, which means cut, and his breathing speeds up.

He grips the edge of the cot with both hands. Lawson places one hand on Walter’s shoulder, firm but not rough, and says something in English that Walter does not understand, but somehow feels. It sounds like reassurance. It sounds like the first gentle thing anyone has said to him in months. Brennan brings over a basin of disinfectant and sets it on a table next to the bed.

Lawson dips his hands in, scrubs them clean, and reaches for a scalpel. Walter closes his eyes. He does not want to see. The first cut is shallow just along the edge of the wound to remove the black tissue. Walter jerks, tries to pull his leg back, but two orderlys are holding him down now. Lawson does not stop.

He works quickly, precisely, peeling away dead skin and muscle, exposing the infection underneath. Blood mixes with pus and disinfectant dripping into a metal pan on the floor. The smell gets worse before it gets better. Lawson cuts deeper. Walter screams. It is a raw animal sound, the kind of noise that comes from a place beyond control.

Brennan leans over and wipes his forehead with a damp cloth, whispering something Walter cannot hear over his own breathing. Lawson keeps going. He has to. If he stops now, the gang green will spread to the bone. And then the only option is amputation. He scrapes away another layer of infected tissue, then another, until he finally sees clean red muscle underneath.

That is the sign he was looking for. The infection has not gone too deep. The leg can be saved. Lawson finishes the debrement and begins flushing the wound with saline solution. The pain eases slightly, just enough for Walter to open his eyes again. He looks down at his leg and sees the wound now twice as large as before, raw and open, but no longer black.

Lawson is applying sulfa powder, an antibiotic agent that will fight whatever infection remains. He wraps the leg in clean white gauze, layering it carefully, then ties it off and steps back. The whole procedure took less than 20 minutes. To Walter, it felt like hours. Brennan brings over a glass of water and holds it to Walter’s lips.

He drinks, coughs, drinks again. His hands are shaking. Lawson pulls up a chair and sits next to the bed watching him. There is no anger in his face, no disgust, no indifference, just focus. Walter has not seen that look in a long time. For the past 3 months, every face he saw carried either hatred or fear.

Guards who spat at him, fellow prisoners who blamed him for losing the war, civilians who threw rocks at transport trucks. But this American doctor is looking at him like he is a patient, not an enemy. It is that realization more than the pain that breaks him. Walter turns his face toward the wall and starts crying.

Not loud, not dramatic, just tears, steady and quiet, the kind that come from exhaustion and relief mixed together. Lawson does not say anything. He just sits there, hands resting on his knees, letting Walter cry. Brennan glances at Lawson, uncertain what to do. Lawson shakes his head slightly. Let him be. After a few minutes, Walter wipes his face with the back of his hand and tries to speak.

His voice is, barely above a whisper. He says something in German that Lawson does not fully understand, but the tone is clear. Thank you. Lawson nods. Brennan writes something on Walter’s chart and clips it to the end of the bed. The guard who was standing at the door earlier reappears and asks Lawson if the prisoner is stable enough to be moved back to the general holding area.

Lawson stands, looks at Walter, then back at the guard, and says no. Walter stays here for at least three more days under observation with daily wound cleaning and antibiotic treatment. The guard argues. He says there are more prisoners coming in, more beds needed, more important cases. Lawson does not move.

He says Walter is an important case and if the guard has a problem with that, he can take it up with the base commander. The guard mutters something under his breath and leaves. Brennan smiles just a little. Walter does not understand the argument, but he understands the outcome. He is staying. For the first time since his capture, he is not being moved, not being loaded onto another truck, not being sent somewhere worse.

He is staying in this room, in this bed with a doctor who just saved his leg and maybe his life. He closes his eyes and for the first time in months falls asleep without wondering if he will wake up. Over the next three days, Lawson cleans Walter’s wound twice daily. Each time he removes the old gauze, inspects the tissue, flushes the wound with saline, applies fresh sulfa powder, and wraps it again.

The infection is retreating. The redness fades. The swelling goes down. The smell disappears. Walter watches every step of the process. Now, no longer afraid to look, he asks Brennan through broken German and hand gestures, “How long until he can walk again?” She holds up two fingers, then three. weeks, not days. Walter nods. He can wait.

On the fourth day, Lawson brings in a translator, a German-speaking American sergeant who was born in Wisconsin to immigrant parents. Lawson wants to know the full story of how Walter got the wound, how long it went untreated, and whether he received any medical care before his capture. Walter tells him everything.

The artillery barrage, the field medic with no supplies, the week of forced marching with an open wound, the infection that started spreading while he was being transported across France in a cattle car, the temporary holding facility where no one looked at his leg for 10 days. Lawson listens, taking notes, asking follow-up questions.

When Walter finishes, Lawson tells the translator to explain something. The infection was gas gang green caused by bacteria that thrive in deep wounds with poor blood flow. If Walter had arrived even two days later, amputation would have been the only option. If he had arrived 4 days later, he would be dead. Walter sits with that information for a long time.

He does not know what to feel. Relief, yes, but also anger. Anger at the war that put him here. Anger at the officers who sent him into artillery fire with no real training. Anger at the medics who had no supplies. Anger at the guards who ignored his leg for weeks. And something else, something harder to name. Gratitude, not for the wound, not for the capture, but for this moment, this room, this American doctor who did not have to care, but did anyway.

Let us know in the comments where you are watching this from. Are you in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, or somewhere else? If you want to dive even deeper into these untold stories, consider becoming a channel member. You’ll get your name mentioned in the video, early access to videos, exclusive content, and direct input on which stories we cover next.

Join our inner circle of history keepers. By the end of the first week, Walter is sitting up in bed without help. His leg still hurts, but it is a clean pain now, not the deep rot that kept him awake for weeks. Brennan brings him soup, bread, and water. Lawson checks his temperature daily and notes that it is dropping back to normal.

Other prisoners in the hospital notice Walter and ask what happened to him. He tells them about the American doctor who saved his leg. Some do not believe him. They think he is exaggerating or that he was only saved because he gave up information. Walter does not argue. He just points to his leg and says he is still walking.

Walter is one of roughly 378,000 German prisoners of war held in the United States during World War II. Most were captured in North Africa, Italy, and France, then transported across the Atlantic to camps scattered across the American interior. The mortality rate for German prisoners of war in American custody was less than 1%, one of the lowest in the war.

That is not propaganda. That is the record. By comparison, the mortality rate for American prisoners of war held by Germany was around 1% as well, though conditions varied wildly depending on the camp. In the Pacific theater, the mortality rate for American prisoners of war held by Japan was over 37%. The reason for the low mortality rate in American camps was not sentiment.

It was policy. The Geneva Convention signed in 1929 set rules for how prisoners of war were supposed to be treated. The United States followed those rules, not out of kindness, but because it wanted the same treatment for its own soldiers captured overseas. That meant medical care, food rations that met minimum calorie requirements, and living conditions that did not amount to deliberate cruelty.

It also meant that wounded prisoners like Walter received treatment even when resources were tight and even when guards objected. By mid 1945, the American military was running over 500 prisoner of war camps and branch camps across the country. Some were large facilities holding thousands of men.

Others were small labor camps attached to farms or factories. The prisoners worked under supervision in agriculture, forestry, and light manufacturing. They were paid a small wage, usually in camp currency that could be used in camp stores. They received mail, could write letters home, and were allowed to organize sports leagues and education programs.

It was not freedom, but it was not extermination either. For prisoners like Walter, it was survival. On the 10th day, Lawson sits down next to Walter’s bed and asks through the translator a question that has been bothering him since the surgery. Why did you wait so long to ask for help? Walter looks at him confused. Lawson clarifies.

You were in allied custody for weeks before you reached this hospital. You must have known the wound was infected. Why did you not ask for medical care earlier? Walter is silent for a moment, then answers. He says he did ask multiple times. At the temporary holding facility, he told guards his leg was infected. They ignored him.

He showed other prisoners the wound. They told him to stop complaining. He tried to get the attention of a medical officer during intake processing. The officer looked at his leg, said something in English Walter did not understand, and moved on to the next prisoner. Lawson listens, his face unreadable.

The translator hesitates before passing the answer along as if he is not sure Lawson wants to hear it. But Lawson just nods and writes something in Walter’s file. Then he asks another question. Did you think we would let you die? Walter does not answer right away. When he does, his voice is quiet. He says he did not know what to think.

He had heard stories about American camps. Some said they were humane. Others said prisoners were worked to death or left to starve. He did not know which stories were true. So, he assumed the worst because assuming the worst kept him from being disappointed. If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel.

We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered. Lawson stands places a hand on Walter’s shoulder and says something in English. The translator repeats it in German. You are not going to die here. Not from this wound. Not if I can help it. Walter nods. He still does not fully believe it, but he wants to.

That is enough for now. Walter spends the next two weeks in the hospital ward. His leg heals slowly but steadily. Lawson removes the stitches. On day 14, the wound is still pink and tender, but it is closed. No longer draining, no longer infected. Walter begins walking again. first with crutches, then with a cane, then on his own.

He limps and Lawson says he probably always will, but he is walking. That is what matters. During his time in the ward, Walter observes the other patients. There are American soldiers recovering from combat injuries, but also other prisoners of war. A French prisoner with pneumonia. An Italian prisoner with a broken arm from a work accident.

A Japanese prisoner with frostbite transferred from a camp in Montana. Lawson treats them all the same way. No favoritism, no cruelty, just medicine. Walter watches and begins to understand something he did not expect. The war for Lawson is not about nations or flags or ideology. It is about bodies, broken bodies that need fixing. That is the only mission he recognizes.

One afternoon, Brennan brings Walter a newspaper. It is in English, but the headline is clear even to him. Germany has surrendered. The war in Europe is over. Walter reads the date. May 8th, 1945. He has been a prisoner for 4 months. The leg surgery happened 3 weeks ago. He sits on the edge of his bed holding the newspaper and feels nothing.

Not relief, not grief, just a strange emptiness. The war is over, but he is still here, still a prisoner, still far from home. He does not know when he will see Germany again, or if there will even be a Germany to return to. Lawson enters the ward, sees Walter with the newspaper, and sits down next to him.

He does not say anything for a while. Then through the translator who happens to be nearby, he tells Walter that the surrender means prisoners of war will start being processed for repatriation. It will take months, maybe longer, but eventually Walter will go home. Walter asks what will happen to Germany. Lawson does not answer. He does not know. No one does.

But he tells Walter that whatever happens, Walter will be alive to see it. And that is more than a lot of soldiers can say. On June 2nd, 1945, Walter is cleared for discharge from the hospital. His leg is healed enough that he no longer needs daily medical supervision. He is transferred to a general prisoner of war camp in Kansas, a sprawling facility that holds over 3,000 German prisoners.

The camp is organized, clean, orderly. There are barracks, a mess hall, recreational fields, a library, even a small theater where prisoners put on plays. It is nothing like the stories Walter heard during transport. It is not a death camp. It is not even particularly harsh. It is just a camp, a place to wait until the war is truly over and the diplomats figure out what to do with all the captured men.

Walter is assigned to a work detail in a nearby wheat farm. He spends his days harvesting crops alongside other prisoners, supervised by American guards who mostly ignore them as long as the work gets done. The labor is hard, but it is not cruel. He is fed three meals a day. He is allowed to write letters home, though he has no idea if they will ever be delivered.

He is allowed to play soccer on Sundays. He is allowed to exist, but Walter does not forget the hospital. He does not forget Lawson or Brennan or the smell of disinfectant or the moment when the infection finally stopped spreading. He does not forget the sound of his own voice breaking when he realized he was going to live.

He tells other prisoners about it and some believe him and some do not. One older prisoner, a former officer, asks Walter why he thinks the Americans treated him so well. Walter does not have a good answer. He just says that Lawson was a doctor and doctors fix people. And maybe that is all there is to it. Walter remains in the Kansas camp until March 1946, nearly a full year after the war ended.

Repatriation is slow, chaotic, bureaucratic. Prisoners are processed in waves, sorted by rank, by capture date, by country of origin. Walter is in one of the later waves because he was captured late in the war and because he is lowranking infantry with no intelligence value. When his name finally appears on the repatriation list, he is loaded onto a train with 200 other men, transported to New York and put on a cargo ship bound for Europe.

The journey takes two weeks. The ship is crowded, uncomfortable, but not brutal. Walter spends most of the voyage on deck staring at the ocean thinking about what he will find when he gets home. He does not know if his family is alive. He does not know if his town still exists. He does not know what Germany looks like now after years of bombing and invasion and collapse.

He does not know what he will do or who he will be in a country that no longer exists in the form he remembers. When the ship docks in France, Walter and the other prisoners are transferred to a British run processing center, then sorted again and sent to different zones of occupied Germany. Walter ends up in the American sector in a small town near the border with what will soon become East Germany.

The town is half destroyed. Rubble fills the streets. Civilians move through the ruins like ghosts, pale and thin and silent. Walter walks through the town looking for his family’s address. The building is still standing barely. He climbs the stairs to the third floor and knocks on the door. His mother opens it.

She does not recognize him at first. Then she does. She pulls him inside and cries. And Walter cries too, and neither of them says anything for a long time. Walter rebuilds his life slowly. He finds work as a laborer helping clear rubble and rebuild homes. His leg still hurts when it rains, and he still limps when he walks too far, but he is walking.

That is more than many of his former comrades can say. He does not talk much about the war or about being a prisoner or about the American doctor who saved his leg. Most people do not want to hear it. They have their own stories, their own losses, their own scars. But sometimes late at night, Walter thinks about that hospital room, about the smell of disinfectant and the sound of Lawson’s voice, calm and steady, telling him through gestures and broken words that everything was going to be all right.

He wonders if Lawson is still a doctor, still saving people, still treating wounds without asking whose side they were on. He wonders if Brennan went back to nursing in a civilian hospital or if she stayed in the military. He wonders if they remember him or if he was just one more patient in a long line of broken men who passed through their ward.

He will never know. He does not have their addresses. Does not speak enough English to write a letter. Does not even know their full names. But he remembers them. He remembers the moment when he thought he was going to die and someone decided he was worth saving. Years later, when Walter’s children ask him about the scar on his leg, he tells them the truth.

He tells them about the shrapnel, the infection, the gang green, the transport, the hospital, the doctor, the surgery, the breakdown, the recovery. He tells them that he was the enemy and the doctor saved him anyway. He tells them that mercy is not weakness and that sometimes the people you expect to hate you are the ones who keep you alive.

His children do not fully understand. They are too young, too far removed from the war. But they listen and they remember and maybe that is enough. Walter dies in 1983 at the age of 57 from a heart attack. His leg, the one lost and saved, is still attached. He walks on it until the day he dies.

The scar is still there. A pale line running down his calf. A reminder of the day he thought his war was over and realized it was just beginning. But also a reminder of something else. That even in the worst moments of the worst war in human history, there were still people who chose to heal instead of harm. That is not a happy ending.

It is just an ending. But for Walter, it was enough.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.