Under Fire and Short on Everything: How a Reluctant Quartermaster Helped America Invent a Worldwide Supply Chain After Pearl Harbor. NU

Under Fire and Short on Everything: How a Reluctant Quartermaster Helped America Invent a Worldwide Supply Chain After Pearl Harbor

I didn’t know the word logistics could make a grown man cry until the winter of 1941.

Before the war, I was a shipping clerk for a coffee importer on the Hudson—one of those jobs where the biggest emergency was a dock strike or a spoiled load that smelled like wet burlap and regret. My days were invoices, cranes, and the small, dependable drama of schedules. Ships came in, ships went out, and if you did your math right and kept your mouth shut, the world stayed orderly.

Then December 7th happened, and the world decided to stop being orderly.

The first sign, for me, wasn’t the radio bulletin or the headlines. It was the telephone. It rang in a way that felt heavier than sound—like it carried weight. A man I’d never met told me to report to a government office near Bowling Green with my employment records, any certifications, and “a willingness to solve problems that don’t have solutions yet.”

I laughed, because that’s what you do when a stranger speaks like a fortune-teller.

He didn’t laugh back.

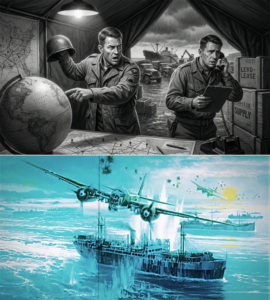

By the time I walked into the office the next morning, the air smelled like wet wool, cigarette ash, and panic disguised as paperwork. The room was full of men with rolled sleeves and hollow eyes. Maps were pinned to walls. Chalkboards were covered in numbers that looked like prayers. Someone had drawn an Atlantic Ocean in blue pencil and then stabbed it with red pins until it resembled a rash.

A short man with a sharp nose looked me over like a foreman evaluating a new wrench.

“Harrison Mercer?” he said.

“Hank,” I corrected, mostly out of reflex.

He didn’t blink. “You’ve moved cargo through New York for twelve years.”

“Coffee and cocoa,” I said.

He tapped a folder. “Now you move everything else.”

He didn’t say for the war. He didn’t have to. The war was already in the room, leaning over every desk, breathing on every neck.

He pointed to a map of the Atlantic. “We have no global supply chain,” he said flatly. “We have a coastline, some railroads, and a bunch of factories that were built to sell refrigerators.”

He leaned closer, voice dropping as if the ocean might overhear. “And now we have to feed Britain, arm Russia, supply our own troops, build ships faster than they’re being sunk, and do it while the ocean is on fire.”

I stared at the pins. I’d never seen the ocean described that way, but it fit. Even from a distance, the Atlantic looked like it had teeth.

“Where do I start?” I asked.

The short man smiled without warmth. “That’s the wrong question, Mercer. The right question is: how many places can you start at once?”

They handed me a desk, a stack of manifests, and a problem that wasn’t a problem so much as a collapsing building.

In 1941, America shipped goods like a big country, not like an empire. You moved things from here to there. You didn’t manage a web of routes that crossed oceans, dodged submarines, rerouted around bombed ports, and still arrived with the right ammo, the right food, the right spare parts, and the right socks.

Nobody had built a machine like that yet.

So we started inventing it with pencils, sweat, and the kind of urgency that makes you swallow lunch whole and forget you’ve been tired for three straight days.

At first, everything was a bottleneck.

Cargo came to the docks in mismatched crates, each one labeled in a different handwriting, some with destination, some with unit names, some with nothing but a prayer and a rusty nail. Half the time, the ship waiting at berth wasn’t the ship the cargo was meant for. Half the time, the cargo wasn’t what the paperwork claimed.

We had trucks lined up like a parade of frustration, drivers smoking and cursing, while stevedores argued over which pile belonged to whom. Meanwhile, the Navy wanted priority for depth charges and aviation fuel. The Army wanted tanks and boots. The British wanted everything yesterday. Someone from Washington wanted numbers—always numbers, as if numbers could make the chaos behave.

My first week, I watched two crates of rifle bolts get loaded onto a ship bound for Iceland while the rifles they fit stayed behind on the pier, headed for Liverpool. Somewhere, months later, men would hold useless pieces in their hands and wonder who had betrayed them.

That night, I went home to my walk-up apartment and sat on the edge of my bed with my coat still on. My hands were blackened from carbon paper and dock grime. I kept seeing those crates separating like two brothers pushed onto different trains.

My kid brother, Tommy, had enlisted in the Marines two months before Pearl Harbor. He’d written me one letter, proud and cocky, teasing me for working with “beans and paperwork.” Now he was somewhere beyond my maps, becoming a man in a hurry.

I lay awake thinking: if the wrong bolts end up in Iceland, what ends up in my brother’s hands?

The next morning I came back with a decision that felt like a vow. We couldn’t fight the war with heroic improvisation. Improvisation was what you did when your engine failed and you hoped the gods liked you. We needed something sturdier: rules.

Rules, in wartime, are not about control. They’re about survival.

I found a corner of the office with a chalkboard and started writing the same question in ten different ways: What is this, where is it going, who needs it, and when?

I wrote another: If it disappears, who dies?

That one stayed.

We created priority codes first, because everyone wanted to be first. We gave each shipment a rating tied to what it supported: aircraft production, naval operations, troop rations. Suddenly it wasn’t just “important.” It was Priority A1 or B3, stamped and tracked.

Then we standardized labels. It sounds small, almost insulting—like bragging about inventing a shoelace during a hurricane—but when you have a hurricane of cargo, a shoelace matters.

We designed a shipping tag with fixed fields: origin, destination port, end unit, content code, weight, cube, priority, and a routing line. It forced clarity where panic wanted to scribble. It was printed in bulk and issued like ammunition.

And then we built the nerve system: communication.

Before the war, if a ship was delayed, someone wrote a note, called a supervisor, and shrugged. Now, if a ship was delayed, a front line could starve.

We used teletype networks and a brutal discipline of reporting. Every port sent daily tallies. Every rail yard reported car counts. Every ship reported position and cargo status. When a ship was rerouted to avoid U-boats, we updated the destination chain like moving a heartbeat from one artery to another.

We didn’t have computers the way people will someday. But we had punch cards, filing systems, and women with quicker minds than any machine. When the office hired new clerks—many of them young women who could sort and calculate faster than the men could complain—I watched the room change. The war didn’t care about old habits. The war cared about results.

Within a month, we could answer questions we couldn’t even ask in December.

Where are the winter coats? How many tons of canned meat are in transit? Which ships carry aviation gasoline? How long until the next convoy reaches Halifax?

We still made mistakes. But the mistakes became visible, and visibility was the first step toward fixing.

The Germans, meanwhile, were turning the Atlantic into a graveyard.

Every morning brought new losses: tankers burning, freighters vanishing, survivors pulled from freezing water with hands that couldn’t hold cups. The pins on our map multiplied. In the office, the sound of typewriters became a kind of prayer.

One evening in February, the short man—the one who had recruited me—walked to my desk and dropped a thin folder.

“Mercer,” he said, “you’re going to sea.”

I blinked. “I’m a shipping clerk.”

“You’re a problem solver,” he replied. “And right now, the problem is that ports don’t talk to ships, ships don’t talk to ports, and cargo becomes a rumor the moment it leaves the pier. You’re going to fix it where it breaks.”

He pointed to the folder. “Convoy HX-174. You sail in three days.”

I wanted to argue. I wanted to say: my job is here, behind the desk, not out there where the ocean eats steel. But then I saw a list of cargo: medical supplies, aircraft parts, radio equipment, and crates labeled for the Eighth Air Force that didn’t officially exist yet in any way that mattered.

I thought of Tommy again, and of rifle bolts separated from rifles.

“All right,” I said. My voice sounded steadier than I felt.

The ship was a Liberty ship—ugly, boxy, hurried into existence by American factories that had learned to weld faster than they had learned to sleep. It smelled of paint, oil, and the sharp tang of new steel. The crew was a mix of merchant mariners and Navy gunners, men who looked like they’d been born with salt under their nails.

The captain, a thick-shouldered man named Reardon, greeted me with a handshake like a vise.

“You the paperwork fellow?” he asked.

“Something like that.”

He grunted. “Just don’t get in the way when the ocean starts throwing punches.”

We sailed out of New York in a cold gray dawn. The Statue of Liberty watched us go, and for the first time in my life she didn’t feel like a monument. She felt like a warning.

Days into the crossing, the convoy became its own moving city: freighters in columns, escorts weaving like sheepdogs, smoke trailing into a low sky. At night, blackout meant the world shrank to darkness and the faintest glimmer of phosphorescence where the sea broke itself against the hull.

My job was to live between worlds. I moved from holds to bridge, from radio room to mess, learning how information died at sea. A port could prepare a ship perfectly, but once underway, reality shifted: a crate broke loose, a storm flooded a hold, a critical part was buried behind something less urgent, and no one on deck knew until it mattered.

I wrote procedures. I annoyed people. I made friends with the chief mate by helping him build a better stowage plan: keep urgent cargo accessible, separate by destination, mark by color-coded tags visible even in dim light. We couldn’t redesign the whole ship, but we could redesign how the ship remembered what it carried.

On the ninth day, the ocean finally threw its punch.

It happened in a moment that felt unreal—an impact without warning, a shudder traveling through the ship like a scream. Then a column of water rose off the starboard side of the freighter ahead of us, and the air filled with the sound of men shouting things that had no place in a civilized world.

“Torpedo!” someone yelled.

The freighter listed, smoke spilling like dark cloth. The convoy tightened, escorts racing, guns barking into empty air, depth charges thumping into the sea with a violence you could feel in your teeth.

I stood on deck gripping the rail until my knuckles hurt, watching a ship burn while the ocean tried to swallow it. My mind didn’t produce heroism. It produced inventory.

That ship had cargo. That cargo had destinations. That destination had people.

When the freighter began to sink, I saw lifeboats—small, fragile shapes—bobbing in the wake.

The captain of our ship didn’t slow.

He couldn’t. That’s the cruel truth of convoy war. If you stop, you invite the wolves. Escorts would pick up survivors if they could. If they couldn’t… you lived with it. Or you didn’t.

That night, in my bunk, I stared at the steel ceiling and realized something that changed me: a supply chain isn’t a line of crates. It’s a line of decisions, and every decision has a human cost.

We made it to Halifax battered but intact. From there, cargo flowed onward—rail to factories, ship to Britain, truck to airfields, an endless relay race run against time and death.

Back in New York, the office looked different. The map had more pins, but the lines connecting them were clearer. We began to build redundancy: multiple ports, alternative routes, stockpiles staged near likely battle zones. We created forward depots—stores of supplies positioned not where they were comfortable, but where they would soon be necessary.

We learned to think like the war: not as a single battlefield, but as a planet-wide argument that required constant feeding.

Then the war expanded again, because the war always expands.

By late 1942, my desk was covered in the names of places I’d never cared about before: Nouméa, Espiritu Santo, Guadalcanal. Tiny islands that suddenly mattered more than cities. The Pacific wasn’t a distance on a map anymore—it was a hungry mouth that demanded fuel, food, bullets, bandages, and spare parts, delivered across thousands of miles of water that didn’t forgive.

When the call came to send me west, I didn’t flinch. I packed my papers like a medic packs morphine.

The day I arrived at a forward base in the South Pacific, the heat hit me like a slap. The air was wet and alive, buzzing with insects and engines. Men moved with a tired intensity, faces streaked with sweat and red dust.

A lieutenant with sunburned cheeks handed me a clipboard. “You’re the supply chain man,” he said.

“I’m the paperwork fellow,” I replied, and he barked a laugh that sounded half-crazed.

“Good,” he said. “Because out here, paperwork is the difference between a Marine having bullets or throwing rocks.”

The port—if you could call it that—was a rough stretch of shoreline with makeshift docks, cranes that groaned like old men, and ships anchored offshore waiting their turn. Everything was improvised, except the need, which was absolute.

We were unloading under threat, always. Sometimes it was aircraft overhead, sometimes it was the fear of submarines, sometimes it was storms that could flip a landing craft like a toy. Each time we unloaded, men looked at the horizon the way city people look at the sky when they hear thunder.

The first time we took incoming fire—distant, sporadic, but real—I was on the dock watching pallets of canned rations being moved from a lighter to a truck. The rounds hit farther inland, but the sound made my stomach clench.

A sergeant beside me didn’t even look up. He just kept counting. “One, two, three,” he muttered, tapping each pallet like it was a rosary bead.

“What are you doing?” I shouted over the noise.

“Making sure nobody steals my lunch,” he said, deadpan.

And there it was again—the war’s strange logic. Fear gets handled the way you handle anything else: by focusing on what you can control.

What I could control was flow.

We didn’t have enough trucks. We didn’t have enough dock space. We didn’t have enough time. So we invented systems in real time.

We created “combat loads,” pre-sorted shipments designed to be unloaded in the order they’d be used: ammo first, medical next, then rations, then everything else. We used color markings that could be read from a distance. We built staging areas inland so the docks didn’t clog. We assigned cargo officers to units so every battalion had a human link back to the depot.

We learned to ship not just things, but capability—repair kits with spare parts and tools, not just replacement machines. A broken radio could be fixed if a crate of components arrived. A plane could fly again if the right gasket, the right bolt, the right length of wire got there first.

I started to see the supply chain like a living thing: arteries and veins, pulses and clots. A delay at one point could cause an amputation somewhere else.

One afternoon, a battered transport came in late, its hull scarred. The manifest was a mess, pages stained and torn. The cargo wasn’t stowed according to plan. Someone had panicked or been attacked mid-load and everything had been shoved wherever it fit.

The dock crew looked at me with the expression of men offered a shovel to dig themselves out of a collapsing mine.

I climbed aboard, sweating through my shirt, and crawled into the hold with a flashlight. Crates loomed like dark furniture. The air smelled of mildew and fuel. I found boxes labeled “MED” buried behind stacks of tent poles and spare tires.

I sat there for a moment, the flashlight beam wobbling, and imagined a field hospital waiting for those supplies. Not in some abstract sense. I pictured men with bandaged arms, nurses with tired eyes, a surgeon holding a tool that wasn’t the right one.

I crawled back out and snapped the flashlight off like it was a weapon.

“Listen!” I shouted to the crew. “We’re not unloading this ship. We’re triaging it.”

They stared.

I grabbed chalk and started marking crates right there on deck as they were exposed, reading labels, assigning priorities. I had clerks rewrite the manifest from scratch as we went, creating a living document that followed the cargo from ship to truck to depot. I sent runners to units with updates: what was arriving, what was delayed, what we could substitute.

For twelve hours we worked in heat and occasional distant bursts of gunfire, sweating, shouting, counting. When the last medical crate hit the dock, the lieutenant who’d greeted me slapped my shoulder hard enough to sting.

“Paperwork fellow,” he said, grinning, “you just saved somebody’s life.”

I wanted to pretend it didn’t hit me, but it did. Because it wasn’t a metaphor. It was arithmetic.

That night, I got a letter.

It was from Tommy.

The handwriting was shaky, as if written in a hurry or after too little sleep. He wrote about rain that never stopped, about mud, about the sound of the jungle at night. He didn’t say much about fighting—most men didn’t. But he mentioned a patrol, a radio that had failed, and how they’d been lucky a replacement set arrived sooner than expected.

“Tell whoever makes that happen,” he wrote, “thank you. Out here, time is everything.”

I read that line until it blurred. Then I read it again, slower.

In that moment, the supply chain stopped being an idea and became a bridge I could stand on. Across oceans. Across fear. Across the gap between a desk in New York and a foxhole under foreign stars.

We didn’t invent the global supply chain in a clean laboratory with applause and ribbon-cuttings. We invented it the way people invent anything when the alternative is losing everything: by failing, learning, standardizing, and refusing to accept that chaos was normal.

We built it with convoys and codes, with standardized tags and priority lists, with radio reports and forward depots, with people counting crates under fire and people rewriting manifests in heat that made ink run like sweat.

It wasn’t perfect. It was never perfect. Ships still sank. Cargo still got lost. Men still went without what they needed. But the machine grew stronger with every correction, every lesson paid for in time and terror.

By 1943, the flow felt different. More certain. More intentional. Ships arrived with loads that made sense. Depots held reserves. Units learned to request what they needed in terms the system could understand. The supply chain began to anticipate, not just react.

And that, more than any speech, felt like victory taking shape.

Near the end of my tour in the Pacific, I stood on a dock at dusk watching a convoy of cargo ships slide toward the horizon. Their silhouettes were dark against a sky the color of bruised peaches. The sea looked calm, deceptively kind.

A young sailor beside me lit a cigarette with shaking hands.

“Think they’ll make it?” he asked, nodding toward the ships.

I didn’t offer him comfort I couldn’t guarantee. I just told him the truth I’d learned the hard way.

“They have a better chance,” I said, “because somebody knows what’s on board, where it’s going, and why it matters.”

He exhaled smoke and stared out at the water.

“What do you do?” he asked.

I thought of the office, the chalkboard, the tags, the maps stabbed with pins. I thought of crates and letters and the sound of a ship shuddering from a torpedo that wasn’t meant for it but didn’t care.

“I keep the world from running out,” I said.

He nodded like that made sense. Maybe, in war, it does.

When I finally went back stateside, New York Harbor looked the same at first glance—cranes, gulls, smoke, the endless slap of water against pilings. But the feeling was different. The harbor wasn’t just a place where ships came and went. It was the heart of something vast, something connected to islands and deserts and frozen seas.

I walked past stacks of cargo stamped with codes I’d helped create, bound for places I could now picture in my sleep. Men shouted. Engines roared. Paper moved from hand to hand like a relay baton.

And for the first time since Pearl Harbor, the chaos didn’t feel like a collapsing building.

It felt like a structure—still rattling, still under strain, still threatened by fire and water—but standing.

Invented under pressure. Reinforced under fire. Kept alive by people who understood, sometimes too late, that the shortest distance between a factory and a battlefield is not a straight line.

It’s a system.

And in 1941, we didn’t have one.

So we built it—crate by crate, ship by ship, decision by decision—until the ocean, no matter how hungry, couldn’t swallow the whole story.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.