A 13-Year-Old German Boy Took His First Hot Shower — He Refused to Come Out for 2 Hours. VD

A 13-Year-Old German Boy Took His First Hot Shower — He Refused to Come Out for 2 Hours

Warm Water in a Cold World

A World War II Story of Compassion

Chapter I: Camp Swift, 1945

Texas, September 1945.

The war in Europe had ended, but its shadows stretched far beyond the ruins of Germany. On the flat, sunburned land between Austin and Houston stood Camp Swift, an American military installation originally built to train infantry divisions. By the autumn of 1945, it served a different purpose: processing the human debris of a shattered continent.

Behind barbed wire fences lived German prisoners of war, displaced civilians, and a small, easily forgotten group—children.

At the edge of the camp stood a modest youth facility housing forty German boys between the ages of twelve and sixteen. Some arrived with mothers who would soon be separated from them. Others arrived alone, carrying nothing but memories they did not yet have words for.

Among them was Hans Weber, thirteen years old, small for his age, his body narrowed by years of hunger. He had been found near Frankfurt in a displaced persons camp—alone, malnourished, and silent. His mother had died during the final chaos of Berlin. His father had vanished years earlier on the Eastern Front. No documents remained to prove who he was or where he belonged.

Hans was placed in a category marked status uncertain. Until someone decided his future, he waited.

Waiting, for Hans, had become a way of life.

Chapter II: The Sergeant

Sergeant James Mitchell managed the youth facility. At thirty-four, he was a father himself, with two sons back in Iowa. That fact shaped the way he saw the boys under his care. They were enemy nationals, yes—but they were also children.

Mitchell noticed how the boys argued over soccer games, how they laughed too loudly at small jokes, how they grew restless during lessons taught by a German-speaking corporal who had once been a schoolteacher. But he also noticed what set them apart from American children.

These boys flinched at sudden noises. They ate quickly, as if food might vanish. Some cried out in their sleep. They carried themselves like refugees, not children.

Hans was the quietest of them all.

He spoke only when spoken to. He avoided games. He kept distance from others, even when invited. The camp doctor noted scars across his back—thin, looping marks consistent with repeated beatings. The diagnosis was simple and devastating: severe malnutrition and psychological trauma.

“Time,” the doctor said. “Safety. Food. That’s all we can give him.”

Mitchell tried kindness. He tried structure. He tried leaving the boy alone. Nothing seemed to reach him.

Until the morning of September 12th.

Chapter III: The Shower

At breakfast, Hans spilled milk on his shirt. It was a small thing, but the boy stared at the stain as if something terrible had happened.

Mitchell approached.

“That’s no trouble, son. Let’s get you cleaned up.”

Fear flickered in Hans’s eyes—not of the sergeant, but of what might be revealed.

The shower facility was a converted building with modern American plumbing. Hot water flowed freely, a detail Mitchell barely noticed anymore. He handed Hans a towel, soap, and clean clothes.

“Red for hot. Blue for cold. Take your time.”

Hans stepped inside and closed the curtain.

The water began to run.

Ten minutes passed. Then twenty.

When Mitchell knocked, a small voice answered, “Yes. I am okay.”

Thirty minutes. Forty-five.

“Please,” Hans said softly. “Not yet.”

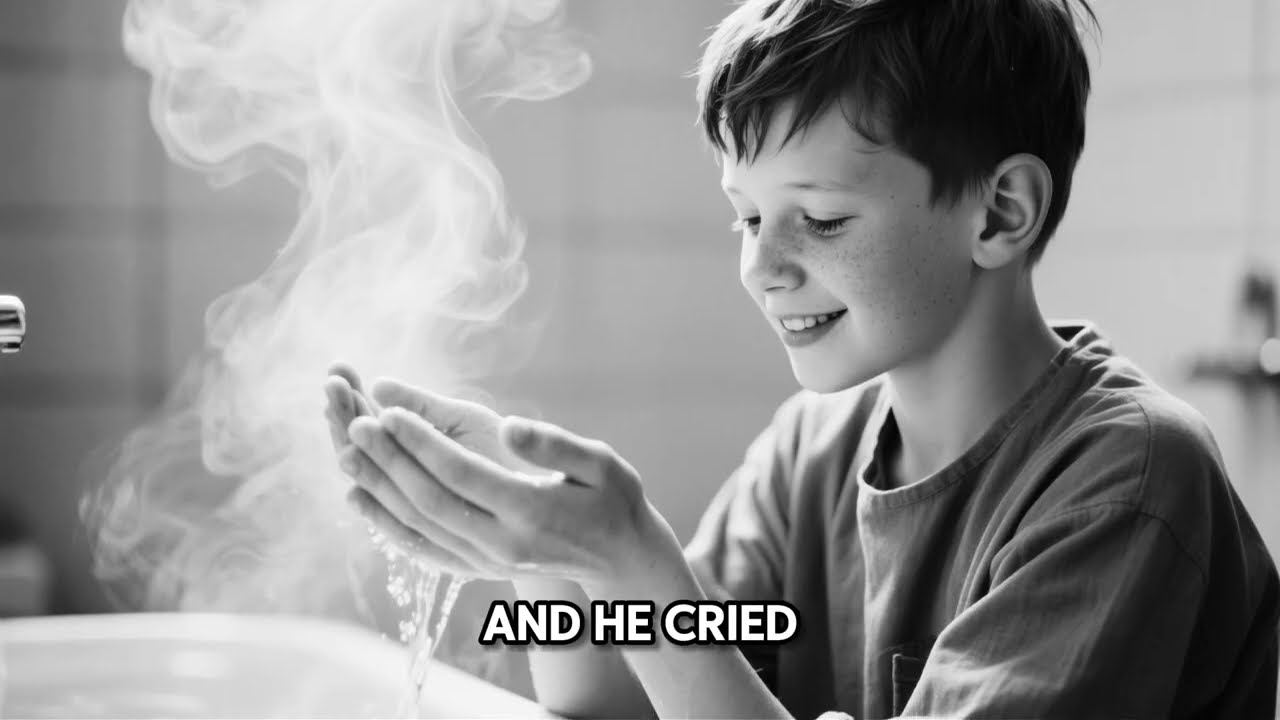

Only then did Mitchell understand. This was not disobedience. This was desperation.

In Germany, Hans explained haltingly, there had been no hot water for three years. Cold rivers. Buckets heated over fires, if fuel existed at all. The war had taken not only safety, but warmth itself.

Inside the stall, Hans stood motionless as hot water ran over his skin. For the first time in years, his muscles relaxed. His body remembered something his mind had nearly forgotten.

Warmth.

He cried quietly, tears indistinguishable from the water. He cried for his mother, who had wrapped him in her coat during the last winter and died from the cold that followed. He cried for the years spent hungry, afraid, invisible.

To Hans, the hot water was not luxury. It was proof that the world could still be kind.

Mitchell sat outside the stall. One hour passed. Then two.

He did not order the boy out.

Chapter IV: Understanding

Captain Robert Chun, the camp doctor, arrived and listened to the water running.

“Let him stay,” he said quietly. “If two hours under hot water teaches him that comfort still exists, that matters.”

When Hans finally emerged, his eyes were red, his face clean, his posture straighter. He looked like a child again.

Later that evening, as he ate slowly in the mess hall, Hans spoke.

“For three years, everything was cold,” he said. “The air. The people. I thought warm did not exist anymore.”

Mitchell listened.

Hans spoke of his mother, of warm baths before the war, of her belief that warmth was a human right. The shower, he said, felt like being cared for again.

The story spread through Camp Swift. Some guards dismissed it. Others understood. The incident found its way into reports, into quiet changes—flexible routines, patience where there had once been rigid order.

Hans began to change.

He played soccer. He asked questions. He spoke to Mitchell about America, about hot water that never stopped running, about a country strong enough to afford kindness to enemy children.

Chapter V: After the War

In January 1946, Hans left Camp Swift. An uncle in Switzerland had been located. Before leaving, Hans thanked Mitchell.

“You let me remember I was human,” he said.

Hans rebuilt his life slowly. He became a teacher. He raised children. He installed the best hot water heater he could afford and never took warmth for granted.

Years later, he wrote to Mitchell:

“Those two hours in the shower changed something fundamental. They taught me that life could be more than survival.”

Sergeant Mitchell kept the letters.

It had only been water.

It had cost almost nothing.

But to a thirteen-year-old boy who had forgotten what it meant to feel warm, it had been everything.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.