Why Canadian Soldiers Forced the “Rich & Famous” German Citizens to Walk Through Concentration Camps. NU

Why Canadian Soldiers Forced the “Rich & Famous” German Citizens to Walk Through Concentration Camps

April 17th, 1945, northern Germany.

The gates swung open the way gates always swing open—on hinges that squealed a little, with iron that looked ordinary enough to belong to any fenced compound in any country. But this gate did not open onto a farmyard or a factory yard or a quiet courtyard where people drank coffee and argued about prices.

It opened onto a place that made language feel useless.

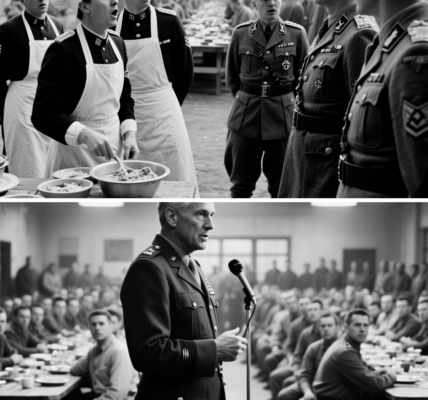

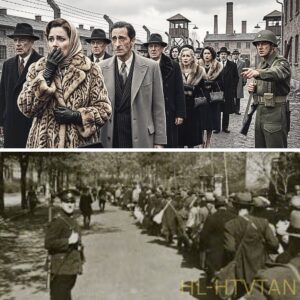

A line of German civilians walked through first—well-dressed, carefully groomed, faces already tightening into expressions they couldn’t control. The women wore their best coats, some of them fur, collars lifted against the chill the way they might have done for church. The men wore clean suits and polished shoes that sank into the dirt as if the ground itself resented the shine. Their hair was combed. Their hands were clean. Their posture said, We are respectable people.

On both sides of the path stood Allied soldiers—among them Canadians attached to the advancing forces—rifles in their hands, faces set into a hard kind of neutrality that had nothing to do with politeness. These soldiers had seen a great deal since Normandy. They had stepped over friends and enemies on beaches and roads. They had lived in ditches and barns and ruined houses. They had smelled cordite and diesel and the sweet rot of smashed villages. They had learned how to keep walking even when the mind begged to stop.

None of that prepared them for what waited behind this gate.

The civilians had not yet seen anything. But the smell hit them like a wall.

It wasn’t a single smell. It was a layered stench of death and waste and sickness that had been marinating in cold air for years. Rotting flesh. Human excrement. Lice and sweat and the sourness of bodies too long deprived of water. Something chemical, too—smoke, ash, the residue of burning. It poured into the nostrils and refused to leave.

Some Germans lifted handkerchiefs to their faces the way people do when passing a dead animal on a road. Others gagged immediately, bending at the waist, retching into the dirt while their polished shoes spattered. A woman with lipstick the color of berries pressed her gloved hand to her mouth as if she could keep herself from becoming part of the smell. A man who had the soft hands of someone who had never dug a ditch tried to step backward.

A Canadian corporal moved one half-step to block him. Not aggressively. Not theatrically. Just enough.

“No,” the corporal said, voice quiet but final.

The civilians looked at him with offended shock, as if they couldn’t believe anyone would deny them the simple right of retreat. For a moment, their dignity tried to assert itself, like a coat being shaken out after rain.

Then the smell reminded them where they were.

The line continued forward, deeper into the camp.

And then they saw.

Bodies lay in piles near the fence, stacked in heaps like firewood—except firewood is cut clean and meant to be used. These bodies were not arranged with care. They had been dropped, dragged, thrown. Many were naked. Skin stretched over bone with a tightness that made faces look carved instead of grown. Eye sockets sank deep. Mouths hung open, frozen in the last shape of hunger or thirst or pain. Some of the dead were so thin they looked unreal, as if a person could not possibly become that light and still be called human.

The German civilians stopped walking.

They stared, mouths open, eyes wide, blinking rapidly like people trying to wake from a nightmare.

A Canadian sergeant stepped into their sightline and pointed—slowly, deliberately—at the bodies.

“Look,” he said.

It was not a suggestion. It was an order.

A man who would later be described as a mayor began to cry immediately, tears streaming down a face that had been well-fed all winter. He repeated a sentence as if repeating it could turn it into truth.

“I didn’t know,” he said. “I didn’t know.”

The sergeant’s eyes stayed flat.

“This camp is five kilometers from your town hall,” he replied. “You could smell it from your office.”

The mayor made a choking sound that might have been protest. The sergeant didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to.

“Everyone knew,” he said. “You just didn’t want to look.”

The mayor had no answer. He stood there, shaking, the scent of death crawling into his fur-lined coat, while in front of him lay people who had starved to death within sight of German homes with warm beds and full cupboards.

But the bodies outside were only the first blow.

Inside the long wooden barracks, people were still alive—if you could call it alive. They lay on bare boards and bunks with no mattresses, bodies covered in sores, skin crawling with lice. Striped uniforms hung off them like laundry on sticks. Some were too weak to sit. Some were too weak to lift their heads. Their eyes—when they had the strength to open them—were the eyes of people who had spent too long in a world without mercy.

A few arms reached out, thin as broom handles, hands opening and closing like they were trying to catch the air itself.

Water, those hands seemed to say. Food. Anything.

The German civilians looked away instinctively, their faces turning toward walls and ceilings, toward any surface that didn’t beg.

The soldiers made them look back.

A Canadian lieutenant—young, with the kind of face that still belonged in a school photograph—stood beside a woman in a fur coat who had pressed herself against the doorway as if she could flatten into it.

“Look at them,” he said quietly. “Look at what you lived next to.”

The woman’s eyes flickered. She swallowed hard, throat moving as if she were trying to force down the entire scene.

“I didn’t—” she began.

A prisoner on a lower bunk coughed—a wet, ragged sound. The cough didn’t sound like illness; it sounded like a body giving up.

The woman flinched.

A soldier took her elbow—not rough enough to bruise, firm enough to anchor.

“You walk,” he said. “You see.”

When the Allied forces arrived, there had been around sixty thousand prisoners in the camp. But “prisoners” didn’t feel like the right word. “People” barely felt like the right word. They were survivors of a system designed to strip the concept of personhood down to nothing but breathing—and even that breathing was failing.

Hundreds were dying every day. Not because the gates were still locked, but because the human body can only be starved and beaten and sickened for so long before freedom arrives like a joke.

There were more than ten thousand bodies lying in the open when the liberators first came in. The Nazis had stopped burying them. They had simply left them where they fell, as if even the act of covering the dead was too much effort for a system already collapsing.

The war was almost over. Everyone knew it. Hitler was cornered in Berlin. The Reich was cracking.

And yet, in the final months, there had still been time to do terrible things. Time to move prisoners from camps in the east as the Soviets advanced. Time to cram human beings into barracks built for a fraction of the number. Time to let disease do what bullets didn’t. Time to kill through neglect as efficiently as through violence.

In the aftermath of the discovery—after the first stunned walk through the corpse piles, after the first breath of the air that made men gag—something else happened among the soldiers.

Anger.

Not the battlefield anger that burns hot and then fades with exhaustion. This was colder. Heavier. The kind of anger that settles in the chest and doesn’t leave.

A Canadian private from Saskatchewan stared at a pile of bodies and felt his mind refuse to accept it. He had grown up on flat land with big skies. His life before the war had been tractors and grain and schoolhouses and the simple certainty that people, even when they were cruel, were at least human in recognizable ways.

This did not feel human.

He thought of his mother and father, of his little sister, and knew—absolutely knew—that they could not imagine this. They would not believe it even if he wrote it down in careful sentences. The smell was in his clothes. It would be in him forever. He would smell it decades later in a hot summer field and suddenly be back here, breathing this air, hearing that cough from the bunk.

He watched the German civilians stumble forward, crying and gagging, and felt something inside him harden.

They said they did not know.

They said it like a prayer. Like a shield.

And in the private’s mind, the sentence rang hollow. The camp was too close. The smoke too visible. The trains too frequent. The rumors too persistent. The stench too strong.

He did not yet have words like “collective guilt” or “denazification.” He did not think in legal terms. He thought in the blunt moral arithmetic of a farmer:

If you can smell a barn on fire from five kilometers away, you don’t get to claim you didn’t know it burned.

Two days earlier, the camp had been liberated. Now the civilians were being marched through. And the question that would haunt many of the soldiers later—the question people would argue about in warm rooms years after the war—was already present, even if it wasn’t spoken out loud:

Why did they do this?

Why did battle-hardened men—men who had survived shells and snipers and the slow, grinding loss of friends—feel compelled to drag the region’s richest and most important Germans into this place and force them to look?

The simplest answer was also the most frightening.

Because the soldiers understood something about human beings:

If you let people look away, they will.

If you let people deny, they will.

If you let comfort write the story, comfort will clean the blood off the page and call it an accident.

So they decided—quietly at first, then with official clarity—that the people living near this camp would not get the luxury of ignorance.

Not anymore.

Bergen-Belsen had started as something the Nazis called an “exchange camp,” a place where certain prisoners might be traded. But as the war turned, it became a dumping ground—thousands evacuated from the east, sick and dying, shoved into a camp built for a fraction of the number. Disease spread like fire. Typhus moved through bodies already weakened by starvation. The system did not need gas chambers here to kill; it used hunger and filth and overcrowding like weapons.

And all of it sat near towns where German citizens lived ordinary lives.

Bergen. Celle. Small places with tidy streets and market squares. Places where people went to work and sent children to school and bought bread and attended church. Places where mayors sat in offices and signed papers and told themselves the war was a distant thing, even as trains full of prisoners passed through local stations.

Trains moved slowly. People could see faces pressed to windows. They could see hands reaching through slats. They could hear cries. Sometimes prisoners were marched through towns on their way to work details, walking skeletons under guard. When anyone asked about the smell or the smoke, the answers came quickly: a factory, burning trash, something else.

Anything except the truth.

And the local officials—mayors, council members, police—knew more than most. Reports crossed desks. Coordination happened. Businesses supplied goods. Contracts were signed. People profited. Others stayed silent because silence was safer than questions.

Now the war had come to their doorstep, and those same people were already building their wall of excuses brick by brick, preparing to claim they were victims too, preparing to insist they had no choice.

The soldiers had heard these excuses before. Every occupied town had its stories. Every collaboration had its justifications.

But in the camp, with bodies piled like discarded furniture and living prisoners begging with hands too thin to be hands, excuses felt obscene.

The order went out—first from senior Allied command, then down through local sectors. Civilians living near camps would be brought in. They would see. They would witness. They would not look away.

So Canadian soldiers—dirty, exhausted, carrying a rage they barely knew how to hold—went door to door with lists.

Not random names. Not the poor. Not the hungry old woman living on the edge of town. The lists were specific: mayors, council members, business owners, the wealthy families, the people whose influence had helped shape the local reality. The people who could have asked questions loud enough to matter and chose not to.

They knocked on the biggest doors first.

A Canadian lieutenant would stand on a doorstep with armed men behind him. When the door opened, he read a name and gave an instruction delivered with the same tone you’d use for a military order, because that was what it was.

“You will come with us to tour the camp,” he said. “Ten minutes. Wear whatever you like. You’ll be walking.”

The protests came immediately.

“I am not a Nazi.”

“I never joined the party.”

“I have nothing to do with this.”

Some offered money. Some threatened complaints. Some tried to argue that they were being punished for crimes they didn’t commit.

The Canadians did not debate. They did not engage the logic. Logic had died in the camp.

If your name was on the list, you went.

Over the next week, roughly two thousand civilians were gathered in groups. They dressed in their finest clothes, as if clothing could serve as armor. Fur coats, hats, polished shoes. A strange instinct—dignity as defense—asserting itself even when dignity was meaningless.

The march to the camp was silent. A few civilians tried to make small talk—asked where the soldiers were from, commented on the weather, tried to treat the event like an unpleasant civic duty rather than a confrontation with atrocity.

The Canadians didn’t respond.

They walked with faces hard as stone.

As the groups approached the camp, the smell reached them again, stronger now. The handkerchiefs came out. The gagging started. A few tried to slow down. Soldiers behind them ordered them to keep moving.

And then the gates.

And then the corpse piles.

The civilians stopped and stared, and the soldiers—again and again—forced them forward. Stop here. Look. Keep walking. Look at the children. Look at the bones. Look at the eyes.

A businessman collapsed into sobs. “I didn’t know,” he repeated, like a hymn.

A Canadian sergeant leaned close enough that the man could smell tobacco and sweat on his uniform.

“You drove past this,” the sergeant said. “You saw the smoke. You smelled it. Everyone knew.”

The businessman shook his head violently, as if he could shake off responsibility like dust.

“You didn’t want to know,” the sergeant said. “That’s what you mean.”

Then the barracks.

The civilians filed in, their shoes tapping wooden boards, their breathing loud in the stillness. Survivors lay on bunks, some too weak to move. Some turned their heads and looked at the well-fed people walking past. Others didn’t bother. A few reached out, arms trembling, begging for water.

The civilians looked away.

The soldiers made them look back.

“This is what happened,” a Canadian officer told them, voice low. “Five kilometers from your home.”

A woman in an expensive coat suddenly turned and tried to walk back toward the door. She had seen enough. She couldn’t take it. Or perhaps she could—she simply didn’t want to.

A Canadian corporal stepped into her path.

“You will walk every meter,” he said.

The woman’s eyes flashed with outrage, then fear.

“I didn’t know,” she said, louder now, as if volume could make it true. “I’m not responsible. I’m a wife. I’m a mother.”

The corporal’s expression didn’t change.

“You lived next to this,” he said. “You breathed the same air.”

She began to cry. The corporal didn’t flinch.

“Keep walking.”

A few fainted during the tour. The smell and sight overwhelmed bodies that had never been forced to confront consequence. Soldiers revived them and made them continue. Vomit in the dirt. Tears. Hands shaking. The performance of horror mixed with real horror until you couldn’t always tell which was which.

And then came the next order.

Seeing was not enough.

Those civilians would also help clean the camp. They would help bury the dead. They would bring supplies for survivors.

If you lived near this place and pretended not to know, you would now work to repair what your silence had allowed.

German men—some still in fine suits—were handed shovels. They dug graves in ground that resisted, cold and heavy. They lifted bodies that weighed almost nothing and placed them into mass pits carved by bulldozers. The bodies did not feel like bodies. They felt like bundles of bone wrapped in paper-thin skin.

Some Germans cried while they worked. Others worked in grim silence. A few still muttered that it wasn’t fair.

The Canadians had no patience for “fair.”

“You dig until they’re buried,” one soldier said. “You work until we stop you.”

German women were told to bring blankets and sheets, food and supplies. Some did, hands shaking, offering items to survivors who stared at them with eyes that held too much memory. A few survivors accepted what was offered. Others turned away. A kind act after years of cruelty can feel less like kindness and more like insult.

Among the soldiers, reactions hardened into different shapes.

Some felt grim satisfaction. Now they see. Now they can’t pretend. Now denial has fewer places to hide.

Others felt only exhaustion. They had seen too much. Their anger had burned down into something like numbness. They did what they were ordered to do because orders were what kept them functioning.

And some—quietly, privately—wondered if forcing civilians through this place was another kind of violence. Not comparable to what the prisoners endured, nothing like that. But still violence—a deliberate imposition of trauma. A decision to make horror contagious.

That question would become part of the postwar debate almost immediately: collective guilt versus individual responsibility. Were all Germans responsible? Did all deserve punishment? Were some victims too? Did forcing civilians to witness atrocity cross a moral line?

The debate remains unresolved because it touches the raw nerve of human society: how to deal with mass crime that required mass silence to function.

But in April 1945, standing in a camp filled with corpse piles and dying survivors, the Canadian soldiers weren’t thinking in philosophical terms. They were thinking in blunt moral truths.

This happened.

It happened here.

It happened near your homes.

If you claim you didn’t know, you are either lying or admitting something else—that you trained yourself not to know.

For many survivors, the forced tours felt like a necessary act of acknowledgement. After years of being treated as less than human, after years of being looked through like ghosts, it mattered—deeply—that the comfortable people who had looked away were now forced to look at them. Forced to see that they were real.

One survivor—skeletal, barely able to sit—watched from a barracks window as civilians filed past. She did not smile. She did not cheer. She only watched, eyes hollow but sharp.

“Now they see,” she whispered to a nurse.

The nurse—also exhausted, also changed—didn’t answer. There was nothing adequate to say.

For some German civilians, the tour shattered something inside them. A few, in later years, would speak openly about shame, about choosing comfort over truth. A man might confess, “We smelled it and called it something else.” A woman might write in a diary, “We knew and didn’t admit it.” Those words, when they appeared later, would be devastating in their simplicity.

But many others—perhaps most—left the camp already building new walls. Yes, it was terrible, they said. But Nazis did it, not us. We were victims too. We had no power. We were afraid. What could we have done?

The excuses came quickly, rehearsed by years of living beside smoke.

The Canadians couldn’t force belief or remorse. They could force witnessing. That was all.

But witnessing mattered.

Because denial is easier when evidence is abstract. When it’s a rumor. When it’s a distant story about “somewhere else.” Witnessing turned abstraction into smell, into sight, into the weight of a shovel and the feel of a dead body in your hands.

And the Allies documented everything.

Photographers captured the expressions—shock, nausea, tears, refusal—on German faces. Film crews recorded civilians walking past corpses, recorded the bulldozers pushing bodies into mass graves, recorded survivors staring at a world that had finally shown up too late.

This footage was not only for the world. It was for Germany.

After the war, German movie theaters showed newsreels of the camps before the feature films. People who wanted entertainment had to sit through reality. They could not avoid it. The evidence became part of the air.

In surveys after the war, absurd numbers appeared: huge percentages of Germans claimed they had secretly opposed the Nazis. Almost everyone said they had never supported Hitler. The numbers didn’t add up. But denial is a powerful instinct, and societies rewrite themselves in self-defense.

Even so, the visual record made certain kinds of lies harder to sustain. You can deny a rumor. You can deny a story. It is harder to deny photographs of your neighbors being marched through the camp gates, harder to deny film of you standing beside a corpse pile.

The forced tours did not “solve” guilt or responsibility. They did not magically create moral reckoning. That process took decades and is still ongoing. But they did something essential: they created a foundation of undeniable truth.

And for the soldiers who carried out the orders—especially the young men from Canada who had fought across Europe and thought they understood horror—the act of forcing civilians to witness became part of how they made sense of what they had seen.

A Canadian private might later write home: We made them smell it. We made them see it. Maybe now they can’t lie.

He might also ask, in the privacy of a letter to his mother: Does it make me hard that I felt no sympathy when they cried?

It was a question with no easy answer. War changes the shape of empathy. Sometimes it breaks it. Sometimes it bends it into something unfamiliar.

But the soldiers who stood guard on that path—rifles ready, eyes cold—weren’t acting out of simple revenge. Many of them would later insist, even decades afterward, that the tours were necessary.

Because the alternative—letting people return to clean homes and claim ignorance—felt like another kind of crime.

To let denial settle would be to let the dead be buried twice: once in the earth, and once in memory.

So on April 17th, the well-dressed citizens of nearby towns walked through the gates.

They gagged. They cried. They fainted. They vomited. They begged to leave. They claimed innocence.

The soldiers did not argue with their excuses.

They simply pointed.

Look.

Keep walking.

Look again.

And whether those civilians truly changed—whether horror turned into accountability or only into shame—was a question the soldiers could not control.

All they could control was the moment.

The moment when people who had lived close enough to smell death were no longer allowed to say they had not known what it was.

The image that remained—burned into memory like a scar—was simple and brutal:

A line of well-fed German civilians in fur and polished shoes moving past piles of human remains, while young soldiers in dirty uniforms stood watch, refusing to let anyone look away.

It wasn’t the kind of liberation celebrated in victory parades.

It was a harder kind.

Liberation from lies.

Liberation from comfortable denial.

A forced confrontation with truth—because after what had been done, truth was the least the world owed the dead.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.