Why US Tankers Started Welding “German Trash” On Shermans — And Saved 1,500 Lives In Days “German Trash” On Shermans — And Saved 1,500 Lives In Days. NU

Why US Tankers Started Welding “German Trash” On Shermans — And Saved 1,500 Lives In Days “German Trash” On Shermans — And Saved 1,500 Lives In Days

The Rhino Cutter: How Curtis Cullen Changed the Battle of Normandy

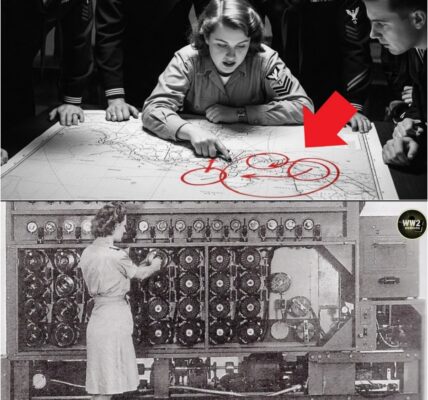

On the morning of July 13th, 1944, Staff Sergeant Curtis “Cullen” Grub watched General Omar Bradley step out of a jeep near St. Lo, France, as the fate of 3,000 American tanks hung in the balance. A hot, sticky day in Normandy’s Bokeage, a region riddled with thick, ancient hedgerows, and the problem at hand was monumental. The Germans had fortified these hedges with stone, making them nearly impossible for the advancing tanks to break through without exposing their vulnerable undersides to enemy fire. It wasn’t just about terrain—it was about survival.

Cullen had spent months watching American tank crews lose their lives trying to advance through this dense terrain. The tanks, mostly M4 Shermans, were too slow, too exposed. The Germans knew it and had planted their anti-tank guns strategically behind these hedgerows. When American tanks tried to climb over these walls of earth and stone, they were easy targets. Sherman crews burned alive before they could even bail out. The death toll was rising, and something had to change.

Cullen, a mechanic with the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron of the Second Armored Division, had been quietly observing the problem from the maintenance sheds. The first few times they attempted to breach the hedgerows with bulldozer tanks, the result was predictable—slow progress and high casualties. The bulldozers were sitting ducks for German anti-tank teams. The Army’s solution—wait for the engineers to blow up the hedgerows—had worked in theory but not in practice. Explosives didn’t provide an immediate solution, and the tanks were still stuck. It was clear: the hedgerows were a strategic nightmare.

But Cullen had a simple idea. It was an idea that came to him after days of walking past piles of steel obstacles—discarded German beach defenses called Czech hedgehogs. They were made of three railway iron beams welded into a jack-like shape, designed to pierce landing craft during the invasion. The Germans had used them to stop the Allied landing forces, but Cullen saw them differently. Why not take those pieces of scrap and use them to breach the hedgerows? Why not weld them to the front of the tanks and drive through instead of trying to climb over?

It was a crazy idea—no one had ever suggested it before, and it was far from the Army’s standard procedures. The official military doctrine didn’t allow for such improvisation. Modifying military vehicles without authorization was grounds for a court-martial. But Cullen didn’t care. His friends were dying, and no one was offering a better solution. So, he took the risk.

He gathered four sections of the Czech hedgehog steel, each piece 2 inches thick, and welded them to the bow plate of a light tank. The prongs, angled at 35 degrees, would dig into the base of the hedgerow instead of the tank climbing over it. The plan was simple: the tank would push through the hedge, with no belly exposure to German guns. It was untested, but it was their only shot.

The first test run on July 12th went off without a hitch. Sergeant William Crawford, the commander of the test Sherman, took it through the hedgerow. The steel prongs dug into the earth and roots, forcing the tank through the barrier. It wasn’t pretty, but it worked. The Sherman didn’t get stuck, and more importantly, no one was killed. Word spread quickly, and by the next day, the device was ready for the real test—a demonstration for General Bradley.

Bradley, the commander of the First Army, was no stranger to the brutality of the hedgerow terrain. The stalled progress of the American forces had frustrated him for weeks. He needed a solution, and Cullen’s idea seemed like the last chance to break the stalemate. At 9:30 a.m. on July 13th, Bradley stood alongside Cullen as Sergeant Crawford and his crew prepared to drive through a 12-foot-high hedgerow. They were going to test whether Cullen’s “Rhino” device could make the difference.

The Sherman accelerated, its engine roaring as it closed the distance to the hedge. At 25 mph, the tank struck the wall of earth with a sound like a freight train collision. For a moment, it seemed like the tank might sink into the earth. But then, with a grinding noise, the prongs dug in, and the tank pushed through. In 14 seconds, the hedge collapsed inward, and the Sherman had cleared the obstacle. General Bradley lowered his binoculars and walked over to inspect the breach. He ran his fingers over the severed roots and dirt, looking at Cullen.

“How many of these can we produce?” Bradley asked, already knowing the answer. He had just seen the future of the battle unfold in front of him.

By that evening, Bradley had issued orders for 3,000 of these devices to be produced for Operation Cobra, the planned breakout offensive. But there was a problem. The deadline was just 12 days away. Bradley needed the devices now. It was an all-out scramble to get the job done.

The 52nd Ordinance Group, tasked with welding the devices, initially struggled with the production. The steel was harder than they anticipated, and the equipment kept overheating. But Cullen wasn’t one to back down. He spent sleepless nights troubleshooting the production line, even bringing in additional welders from other battalions. By July 19th, they had made substantial progress, with 64 devices completed each day. But the clock was ticking, and the need for 3,000 devices was still a daunting task.

The solution came when Cullen discovered the hedgehog steel was putting too much strain on the tank’s suspension. With his hands blistered and exhausted from the constant work, Cullen re-engineered the mounting system, redistributing the weight across the tank’s hull. This modification added time to each installation, but it ensured that the tanks could endure the stresses of combat without breaking down.

By July 23rd, just two days before Operation Cobra, the team had managed to modify 2,300 tanks, just above the required number. The operation would go ahead as planned.

On July 25th, 1944, the ground near St. Lo shook as 1,500 Allied bombers dropped 4,000 tons of explosives on German positions. As the bombardment ended, the tanks rolled in. For the first time in weeks, the American tanks could push through the hedgerows, not climb over them, exposing their vulnerable bellies to German gunfire. The Rhinos worked. American forces moved faster than they had in the past six weeks.

Reports began coming in: tanks were pushing through hedgerows in minutes instead of hours. The prongs held up under the stress, and the German defenses were crumbling. The hedgerows that had been a barrier for so long were no longer an obstacle. It was a breakthrough.

But not everything was perfect. There were some failures. A few tanks hit obstacles too large for the prongs to breach, and some of the modified tanks had issues with the suspension. But the failures were minimal compared to the overall success. The battle continued, but the American tanks had gained a crucial advantage.

As the battle of Operation Cobra continued, Bradley’s staff realized the massive impact the Rhino device had on the success of the campaign. American losses were far fewer than expected, and the speed at which they advanced was unprecedented. The devices had broken the deadlock that had plagued the American forces in Normandy.

By the end of July, the production of the Rhino device had spread across the Allied forces, and even the British and Canadian armies had started using it. The device that Cullen had created in a quiet, makeshift workshop had saved thousands of lives and changed the outcome of the battle.

General Bradley, recognizing the importance of the Rhino device, awarded Cullen the Legion of Merit for his exceptional ingenuity and technical skill. In a ceremony on August 20th, 1944, Bradley himself pinned the medal on Cullen’s uniform. The citation praised Cullen for his contributions, but in truth, the impact of the device went far beyond just one man’s innovation.

Cullen, however, didn’t care for the recognition. He had done what was necessary to save his fellow soldiers, and that was all that mattered to him. After the war, Cullen returned to civilian life, and his name faded into obscurity. Few people knew who he was or what he had done. But the men who survived because of his invention never forgot.

In the years that followed, the story of the Rhino device was passed down through military circles. Military historians and veterans alike recognized the brilliance of the modification and its impact on the course of the war. By the 1950s, the Army had incorporated the idea of field improvisation into its doctrine. The concept of solving tactical problems using available materials had become an integral part of military thinking.

Curtis Cullen’s story remains one of the countless unsung tales from World War II. While his name is rarely mentioned in history books, his contribution was vital. His simple modification—born out of necessity and ingenuity—saved countless lives and made an enduring impact on modern military tactics. He was a mechanic, a soldier, and a quiet hero. And in the end, that’s what really mattered.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.