“My Son Would Be Your Age” — A German POW Father Told a Young American Guard Who Looked Like His Son. VD

“My Son Would Be Your Age” — A German POW Father Told a Young American Guard Who Looked Like His Son

THE HORSE CARVED FROM SILENCE

A World War II Story

Chapter I – Roll Call on the Prairie

Nebraska, autumn 1944.

The prairie wind moved softly across Camp Atlanta, carrying with it the smell of turned earth and distant rain. The sky stretched endlessly above the barbed wire fences, so vast it made human conflicts feel temporary, almost insignificant.

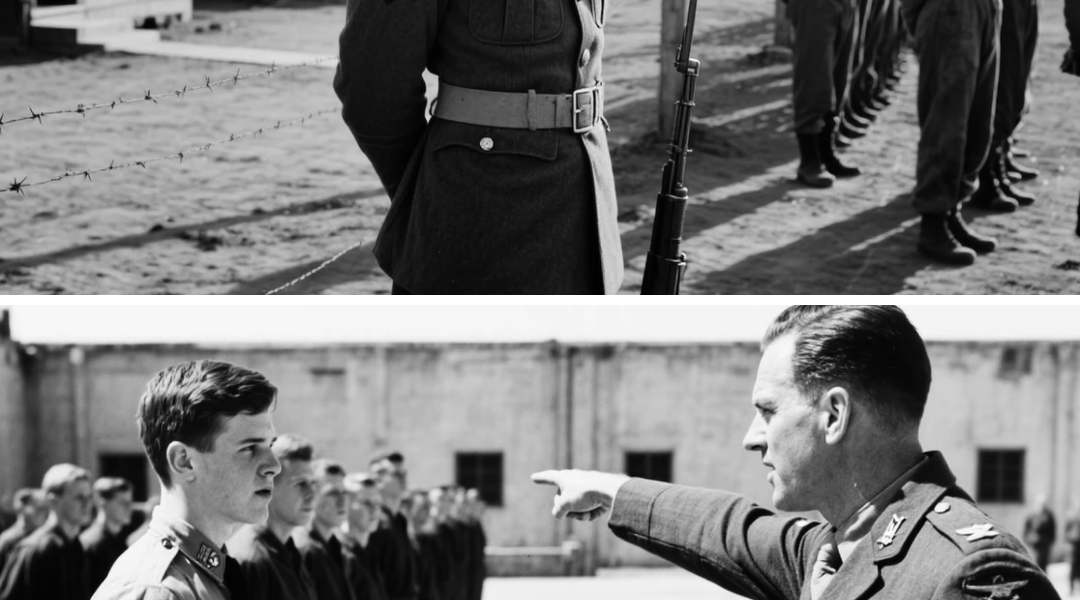

Private David Mitchell stood at attention beside the guard tower as German prisoners filed past for evening roll call. He was nineteen years old, newly assigned, his uniform still stiff with newness, his posture drilled into precision by weeks of basic training. He had imagined war as noise and motion—gunfire, shouted orders, sudden terror. Instead, his days were quiet and repetitive, filled with counts, inspections, and long hours of watching men who were supposed to be enemies but mostly looked tired.

One prisoner stopped.

He was older than the rest, his hair streaked with gray, his shoulders sloped from years of labor. He stared at David with an intensity that made the young guard shift his weight uneasily.

The man’s hands began to tremble.

“My son,” the prisoner said in halting English. “He would be your age.”

David blinked, uncertain how to respond.

“He looked like you,” the man continued. “Same eyes. Same face.”

The words caught in his throat.

The line behind him stalled. A guard barked an order, and the prisoner moved on, disappearing into the ranks.

But something had already changed.

David stood there, the prairie wind brushing his face, wondering how a stranger’s grief had crossed the distance between enemy and guard so effortlessly.

Chapter II – The Men Behind the Wire

Camp Atlanta held nearly three thousand German prisoners of war, captured in North Africa and Europe and transported across an ocean to work American farms while the world burned elsewhere.

David had arrived in August, assigned to guard duty after basic training at Fort Leonard Wood. He was the youngest of four brothers, the only one who had not gone overseas. A heart murmur had delayed his enlistment until it resolved itself, leaving him with a lingering sense of guilt that he carried quietly.

The work was monotonous. Morning roll calls. Escorts to sugar beet farms. Evening inspections. Training had warned him not to fraternize, to maintain professional distance. These men were enemy soldiers, potentially dangerous.

Yet it was hard to see danger in men who wrote letters home in the evenings, who spoke of wives and farms and classrooms left behind.

The older prisoner was named Carl Schneider.

He was forty-two, from near Hamburg, a schoolteacher before the war. Drafted in 1940, he had served in multiple campaigns before being captured in Italy. The labor assigned to him—long days in the fields—was exhausting but familiar. He had grown up on a farm, knew the rhythm of working the land.

Carl noticed David as well.

The young guard stood straight, never cruel, never mocking. He enforced rules without malice. There was something about him—his face, his stance—that stirred memories Carl had tried to keep contained.

Memories of his son.

Chapter III – A Son Named Hans

Hans Schneider had been seventeen when he was conscripted.

Germany was desperate by then, pulling boys into uniforms when men were gone. Two weeks of training. A rifle too heavy for his frame. Orders that sent him east.

Carl had received the letter while stationed in Sicily.

It arrived like any other piece of mail—thin paper, formal language, stamped and processed without care for what it carried. It informed him that his son had been “lost on the Eastern Front.” No body recovered. No details. Just loss reduced to bureaucracy.

Carl had read the letter alone in his tent, the Mediterranean night warm and still around him. He folded it carefully and put it in his pocket, because soldiers were not allowed to fall apart. Grief was a luxury combat did not permit.

Eighteen months later, seeing David Mitchell standing at roll call, that grief broke free.

Carl approached him cautiously one evening after the prisoners dispersed.

“I mean no trouble,” he said. “I only wish to speak.”

David hesitated, hand instinctively moving toward his sidearm, then stopped. Something in Carl’s face—desperation mixed with restraint—made refusal feel wrong.

“You look like my son,” Carl said quietly. “When I see you, I see what he might have become.”

David felt pity and discomfort at once. He had never lost anyone close. He had never held grief that deep.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

The words felt small, but Carl nodded as if they mattered.

Chapter IV – Quiet Understandings

Their conversations were brief and careful, never crossing into open friendship. A nod here. A few words about the weather. Sometimes Carl spoke of Hans, never for long, as if naming him was both pain and relief.

David listened.

Sergeant Frank Morrison noticed.

“You’re spending time with that prisoner,” Morrison said one afternoon. His tone was firm but not unkind. “Be careful.”

“He lost his son,” David replied. “A boy my age.”

“I know,” Morrison said. “And it’s good you treat them decently. That’s what separates us from what we’re fighting. Just don’t take on grief that isn’t yours to carry.”

But David already had.

He thought of Hans often. Of a boy sent to die before he had lived. He began to understand that war’s deepest casualties were not always the ones who fell on battlefields.

As winter approached, Carl fell ill. The cold and years of labor caught in his lungs. David mentioned it to Morrison, who arranged lighter duties for the older man.

“You’re protecting him,” Morrison observed.

“I’m doing my job,” David replied. “Making sure prisoners are treated humanely.”

Morrison studied him for a moment.

“That’s exactly your job,” he said.

Chapter V – The Carved Horse

Christmas came quietly to Camp Atlanta.

There were small allowances—songs, extra rations, a simple service. The prisoners sang softly in German, voices carrying longing more than celebration.

On Christmas Eve, Carl approached David holding something wrapped in cloth.

“For you,” he said.

Inside was a small horse carved from scrap wood, its lines smooth and careful, shaped by skilled hands during stolen moments in the carpentry shop.

“I cannot say thank you properly,” Carl said. “But this… this is something I made.”

David hesitated. Regulations forbade gifts.

But some moments demanded more than obedience.

“Thank you,” he said, slipping the horse into his pocket.

That night, David wrote home. He tried to explain how guarding prisoners had taught him more about humanity than any battlefield might have. He wrote about Carl. About Hans. About how enemies were often just people trapped by decisions made far away.

Chapter VI – What Endures

The war in Europe ended in May 1945.

David was discharged that summer and returned to Ohio. He went to college on the GI Bill and became a teacher. On his desk sat a small wooden horse.

Carl returned to Germany months later. He found his wife alive, his city in ruins. He taught again, helping rebuild not just schools, but trust.

They never met again.

Years passed.

Decades later, David’s grandson found the horse while clearing an attic.

“It was a gift,” David’s daughter said. “From a German prisoner your grandfather guarded. A father who lost his son.”

The boy held the carving carefully, sensing it carried more than wood.

At Camp Atlanta, now long repurposed, a photograph remains—German prisoners at roll call, an American guard standing watch.

If you look closely, you can see them.

A father who lost his son.

A young American soldier who chose compassion without abandoning duty.

Between them, in a moment of recognition, something survived the war.

Not victory.

Not defeat.

But humanity.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.