- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- (1945) Female Japanese POWs Thought American Men Were Myths—Then They Saw Cowboys, Lumberjack. NU

(1945) Female Japanese POWs Thought American Men Were Myths—Then They Saw Cowboys, Lumberjack. NU

(1945) Female Japanese POWs Thought American Men Were Myths—Then They Saw Cowboys, Lumberjack

The Prisoners of Abundance

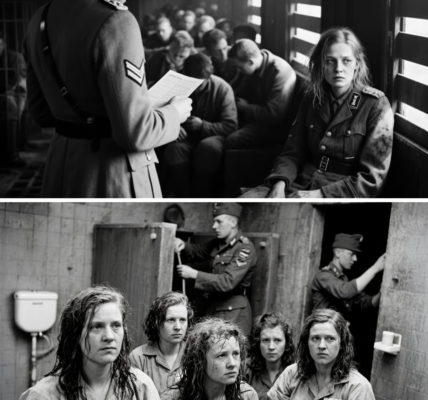

August 15th, 1945, marked a pivotal moment in the life of 23-year-old Yumiko Tanaka, a former communication specialist in the Imperial Japanese Navy. As she stood on the dusty parade ground of Camp Kennedy in Texas, her eyes narrowed against the harsh tropical sun, her mind racing to comprehend the shocking scene unfolding before her. Before her stood an American soldier—tall, imposing, and effortlessly confident. His presence defied everything Yumiko had been taught to believe about her enemies.

“This can’t be real,” she whispered to Akiko Yamamoto, a fellow prisoner beside her. The figure of the American guard before them was the opposite of what they had been taught to expect. He was not the weak, stunted creature that Japanese propaganda had promised. Instead, he was a towering figure with broad shoulders, hands that could encompass her face, and a posture that spoke of strength, of someone who had never known true hunger.

In that moment, Yumiko’s understanding of the world and her captors shattered. The teachings of her homeland, fed to her through years of government-controlled education, crumbled under the weight of what she saw with her own eyes. These men were not inferior beings, they were powerful, healthy, and strong—everything the Reich’s propaganda had told her was a lie.

The story of how Yumiko and other Japanese women prisoners slowly came to this realization begins years before. The war, which had taken them from their homeland, had been carefully framed by the Imperial propaganda machine. For decades, Japanese citizens, especially women like Yumiko, had been fed a vision of America as a crumbling, chaotic empire, driven by poverty, racial inferiority, and moral degradation. This picture was carefully crafted to serve the ambitions of a war-hungry leadership determined to expand Japan’s reach, and for Yumiko and her peers, it was gospel.

From their childhood primers to their military training manuals, they were taught that Americans were weak, stunted creatures with malnourished bodies and fragile psyches. They were indoctrinated to believe that American soldiers were poorly equipped, sluggish, and would fall easily in battle. They were led to believe that the Japanese way—their superior spirituality, their diet, and their devotion to discipline—would win them the war.

Yumiko had been raised on this diet of hate and fear. She had grown up believing in the superiority of her people, the righteous nature of their cause, and the inevitability of their victory. But when the war turned in 1944, and she was captured during the fierce battle for Okinawa, she faced a reality she had never expected.

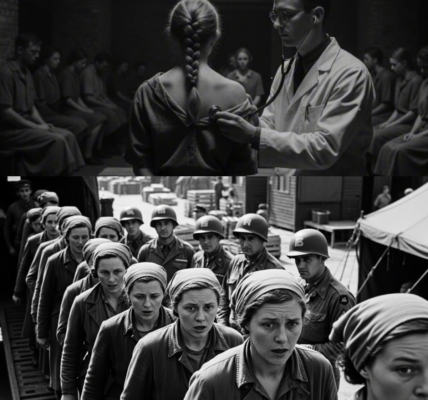

As Yumiko and her fellow prisoners were transported to various camps in the United States, their first encounters with American soldiers quickly began to contradict everything they had been taught. These were not men of weakness. These were men of extraordinary strength, physicality, and confidence. They moved effortlessly, carried themselves with ease, and their physical presence spoke of vitality and power.

“How can this be?” Yumiko wrote in her diary, her disbelief growing with every passing day. “These men, these Americans, are not the weaklings we were told about. They are giants, carved from oak.” The propaganda images she had grown up with—the narrow, hunched American soldiers—had never prepared her for this.

The revelations continued as the women were processed and assigned to camps across the U.S. Yumiko and her fellow prisoners received daily meals that, though simple, far exceeded the paltry rations they had survived on back in Japan. “One meal here,” she wrote, “is enough to feed a Japanese family for a week.”

At Camp Livingston in Louisiana, where Yumiko was temporarily housed, the camp’s food supply alone provided enough evidence to destroy the false narrative of American weakness. The Japanese prisoners, whose wartime rations in Japan had consisted mainly of rice, small portions of meat, and very little fruit or vegetables, were now served three meals a day, with plentiful portions of meat, vegetables, eggs, and even milk—something virtually unheard of in wartime Japan. The American guards, casual in their approach, shrugged at what the prisoners saw as an unimaginable luxury.

For the first time in their lives, Yumiko and her fellow prisoners were able to rest, eat well, and recover from the wounds—both physical and psychological—that the war had inflicted on them. They had believed they were being sent to a nation of barbarians, but what they encountered was a world of abundance.

The contradictions piled up. American men, they had been taught, were weak, incapable of endurance. Yet Yumiko saw them performing physical feats with ease, carrying heavy crates and cutting down trees without a second thought. They laughed and joked, lifting weights that would have taken four or five Japanese soldiers to carry. “These are not special men,” Yumiko thought, “these are just ordinary men, and they are stronger than any I have ever seen.”

As the women adjusted to life in the camps, another shocking realization emerged. They had been told that the American military was technologically inferior, their weapons subpar, and their industry incapable of sustaining a long-term war. Yet, what they encountered defied every preconceived notion they had about America. From the American farm machinery they saw during their travels, to the high-tech medical equipment used to treat them, everything was more advanced than anything they had been taught to believe.

The physical and emotional transformation of the women from soldiers of the Imperial Army to witnesses of American power was profound. The Americans not only fed them better food, but they also provided them with medical care and infrastructure that was impossible to imagine in their own war-torn country.

As the months wore on, Yumiko and the other prisoners found themselves drawn into conversations with the American guards and camp workers. They learned of the immense industrial power of the United States, with factories that produced goods at a scale that seemed unimaginable to them. The numbers—hundreds of thousands of tons of steel, thousands of bombers and tanks—began to sink in. Their beliefs about American inferiority started to break down, piece by piece.

By the time the war ended, the transformation in the women who had been captured was profound. Many of them had come to realize that the United States, far from being a dying empire, was a thriving, powerful nation capable of achieving unimaginable feats. They had learned, in the most painful way possible, that the war had never been about fighting for racial or moral superiority, but about an industrial war of unprecedented scale.

As Yumiko stood in Camp Kennedy on that fateful day in August 1945, watching the towering American guard tip his hat, she realized something that would stay with her for the rest of her life: Japan had been wrong about everything. The battle for supremacy was not one of spirit or ideology, but one of industry. And in that battle, the United States had already won.

What happened next would shake Yumiko’s understanding of both the war and the future. She was not just a prisoner; she was a witness to a new reality. A reality where the power of America was not in its soldiers, not in its ideology, but in its capacity to produce, to provide, and to sustain. As the war ended, Yumiko’s world shifted in ways she never could have imagined, and it was a shift that would change the course of history—not just for her, but for Japan and the world.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.