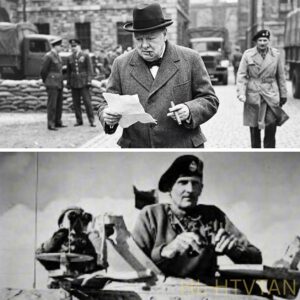

What Churchill Said When He Found Out Montgomery Claimed Credit For Canadian Victories. NU

What Churchill Said When He Found Out Montgomery Claimed Credit For Canadian Victories

July 1944, London.

The city still carried the scars of the Blitz the way a boxer carries old bruises—quietly, permanently, as part of the face. Whole blocks ended in jagged gaps where brick and timber had once been neat rows of homes. At night, when the lamps were dimmed and the curtains drawn, London could feel like a place holding its breath. But inside Number 10 Downing Street, the war did not sleep. It lived in paper, ink, smoke, and the relentless scrape of boots in corridors.

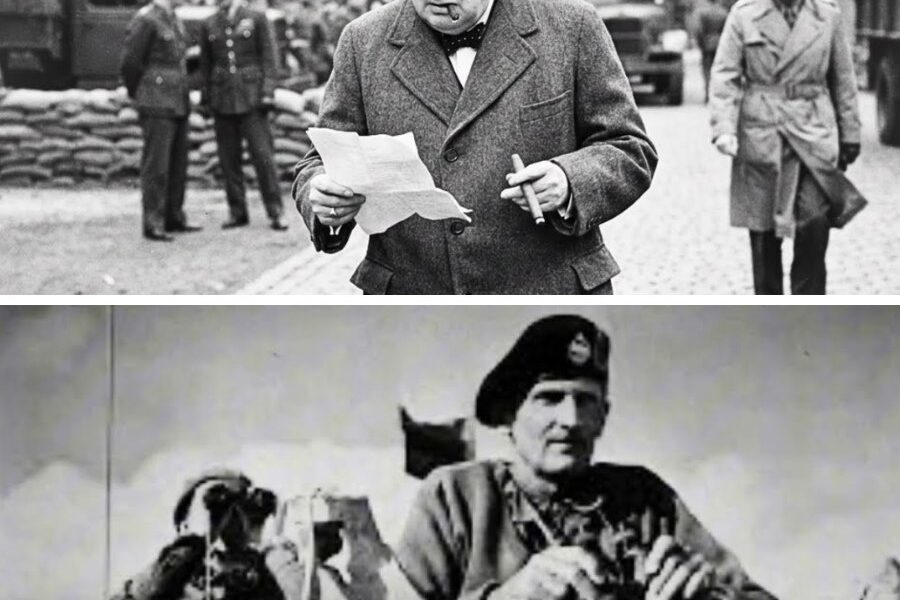

Deep within the war rooms, where the air smelled of old leather and cigar ash, Prime Minister Winston Churchill sat at his desk beneath the hard glow of lamps. Maps covered the walls—France, Belgium, the Netherlands, thick with pins and colored strings. Lines crawled across them like wounds that would not close. Reports lay stacked in piles; each one was another measure of blood and steel.

Churchill held a telegram between thick fingers. His cigar, usually a proud extension of his will, sat forgotten at the corner of his mouth. He read the words once. Then again. And as he reread them, something in him darkened—not the tired dark of a man near the end of his strength, but a furious dark, the kind that rose from a deep place and made the skin flush.

The telegram had come from Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Britain’s most celebrated commander, the man the newspapers had turned into a symbol. It spoke of the battle for Carpiquet airfield, near Caen. It spoke of positions secured. Of clever tactics. Of successful advance.

And it called the victors “British forces.”

Churchill’s eyes narrowed until they were almost slits. He knew—he knew—what that airfield had cost. He knew the way the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade had fought there, moving through hangars like cathedrals of metal, clearing room after room with grenades and bayonets. He knew the smell of that kind of fighting even from a continent away: cordite and sweat, fear and courage mixed so tightly you could not separate them. He knew that young men from Winnipeg and Toronto and Montreal had bled on concrete while Montgomery, miles away, posed for the cameras with his beret angled just so.

Three hundred seventy-seven Canadian soldiers had fallen taking that airfield. Three hundred seventy-seven families would receive telegrams that made their kitchens tilt, their chairs feel suddenly too empty. Three hundred seventy-seven mothers would read the words and go quiet forever.

Churchill crumpled the paper in his fist until it was no longer a telegram but a rough ball of anger.

An aide hovered near the doorway, uncertain whether to step forward or retreat. In the government, everyone knew Montgomery’s habit. Everyone knew his hunger for credit, how he could turn other men’s sacrifices into his own legend without so much as a blush. But Montgomery was also winning. He was the man who had given Britain victories it desperately needed. To criticize him felt, in some minds, like criticizing the war itself.

Churchill looked up, and his blue eyes were bright with heat.

“British forces?” he growled, the words rough as gravel. “Does Monty think I’m blind? Deaf? Senile?”

The aide said nothing because there was nothing safe to say. Behind Churchill’s rage was something heavier than pride. He wasn’t thinking about headlines in London. He was thinking of telegrams crossing the Atlantic—thin sheets of paper that would shatter families. He was thinking of Ottawa. He was thinking of Prime Minister William Mackenzie King, who kept sending messages that were becoming less polite with each week. He was thinking of promises made and promises threatened by one man’s vanity.

By July 1944, Canadian soldiers had been fighting in Normandy for a month, and it had not been a clean month. It had been the kind of fighting that ground men down into something raw. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade were not playing supporting roles. They were being used where the fighting was thickest. They had been assigned what many at the front quietly understood: the hardest work.

Caen had been supposed to fall on D-Day. In the grand plans of generals, it had been an objective you circled confidently, as if ink could force reality to obey. But Caen had not fallen on D-Day. It had not fallen for six long weeks.

The Germans defended it with fanatic determination. Elite SS divisions treated every street corner like a last stand. Every house became a fortress. Every orchard became a killing field. The Canadians attacked again and again. They pushed forward over open ground under machine-gun fire that turned the air into a swarm of invisible knives. They cleared buildings with grenades, climbed stairs into darkness, stepped into rooms not knowing if the next second would be their last.

Over the course of Normandy, more than eighteen thousand Canadian soldiers would become casualties—killed, wounded, missing. For a country of barely over eleven million people, it was a staggering drain. Every town back home would feel it. Every church would have names added to plaques. Every school would have empty seats.

Yet Montgomery’s press conferences—so carefully staged, so neatly delivered—rarely said “Canada.” He spoke of “British troops,” of “my forces,” of “our success.” The Canadian blood soaking into French soil remained invisible in his official language.

And Churchill had promised Mackenzie King it wouldn’t happen. He had given his word that Canada’s sacrifice would be recognized, that Canadian dead would not be tucked into the margins of British glory.

Canada’s contribution to the war was not the obedience of a colony. It was a choice.

Canada had sent over seven hundred thousand men and women into uniform. They came from farms and fishing villages, from lumber camps and city streets. They crossed the Atlantic knowing they might never return. They did it not because London commanded them, but because they believed tyranny had to be stopped.

Canada could have stayed home. Canada could have hidden behind oceans and polite distance and the comforting lie that Europe’s storms never reached North America. But Canada did not. Canada volunteered.

And now—now Canadian boys were dying for an Allied cause that Montgomery’s language kept describing as British triumph.

Churchill understood the danger in that better than most. Britain needed Canada—not as a sentimental symbol, but as a pillar of survival. Britain needed Canadian wheat to feed a population under strain. It needed Canadian factories building tanks, planes, ships, shells. It needed Canadian soldiers filling ranks while Britain ran out of men. It needed the Commonwealth to remain united because the Empire was still Britain’s claim to global power. Without the Dominions—without Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa—Britain was just an island with debts and dwindling strength.

Montgomery’s ego threatened all of that.

Churchill had spent months smoothing over the problem, defending Montgomery, assuming that a private word or two would fix it. But the telegram in his hand—“British forces secured Carpiquet”—was too much. Three hundred seventy-seven casualties were not a footnote. They were not “support.” They were the main effort. The key sacrifice. The hinge on which that small victory turned.

Churchill stood from his desk with sudden force, the chair scraping back. He walked to the window and stared out at London’s broken skyline. The war had already cost Britain so much. It could not afford to lose Canada too. He turned back to his aide, decision hardening in him like cooled metal.

“This ends,” he said. “Now.”

The question was how.

Montgomery was vain and stubborn. He was also useful—dangerously useful. The war in France was not finished. Battles were still being won or lost by the movement of divisions and the nerve of commanders. Churchill could not simply remove Montgomery without risking chaos. And the public adored him. In newspapers, Montgomery was a hero. In pubs, his name was spoken like a talisman. To discipline him openly was to risk shaking morale.

But what was morale built on if not truth? What was the point of victory if it required lying to allies?

Churchill’s anger was sharpened by memory. Montgomery’s legend had begun in August 1942, when he took command of the Eighth Army in North Africa. Britain had been desperate then. Rommel had been winning. The British army’s confidence was cracked. Then Montgomery arrived and changed the tide, winning at El Alamein, and the British press seized him like a drowning man seizing a rope. His face appeared on magazine covers. His beret became an icon. Britain finally had a hero.

But Churchill remembered what the newspapers often ignored: Montgomery’s victories were not purely British. At El Alamein, men from across the Empire had fought and died—Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians. Yet the triumph had been packaged as British, and Montgomery’s name had been stamped across it. The pattern followed him into Sicily, into Italy, and now into France.

By 1944, Montgomery commanded Allied ground forces for the invasion. Under him served British, American, and Canadian armies—an alliance held together by necessity. Canadians were led by General Harry Crerar, and they were no longer green recruits. They had fought through Sicily and Italy. They were experienced, professional, and tough.

Canada itself had transformed in five years. In 1939, Canada’s peacetime army had been small enough to feel almost symbolic—thousands, not hundreds of thousands. It had few tanks, few modern planes, a navy that hardly registered on the world stage. But by 1944, Canada fielded one of the world’s largest navies and air forces by sheer production and effort. Canadian factories had poured out aircraft, vehicles, ammunition on a scale that seemed impossible for a nation of its size. Canada had become a war machine not because it loved war, but because it understood what was at stake.

Canadian soldiers carried an old reputation, too—earned in the First World War. Vimy Ridge. Passchendaele. Battles that had burned “Canadian” into German minds as something dangerous. In this war, Canadians proved again they could take hard objectives and keep moving. Even disaster had hardened them: the raid at Dieppe in 1942, a bloody failure that cost them terribly, had taught lessons that made later successes possible. In Sicily, Canadian divisions had taken ground and prisoners at a pace that impressed even skeptical British officers.

Churchill appreciated that more keenly than many of his colleagues. Perhaps it was because his mother had been American; perhaps because he understood North America’s rising power and Britain’s fading dominance. He had visited Canada, spoken to Canadian Parliament, called them partners. He meant it—and he knew that partnership required respect.

So when Canadian journalists began asking why Canada was invisible in victory reports, Churchill listened. When Mackenzie King sent concerned telegrams, Churchill promised it would be fixed. He spoke privately to Montgomery. He assumed the Field Marshal would understand.

He had been wrong.

Montgomery did not change. Or did not care to.

In Montgomery’s mind, he commanded British Commonwealth forces, therefore calling them British was “proper practice.” The political meaning of those words—how they landed in Ottawa, how they tasted on Canadian tongues—either escaped him or did not interest him. He wanted British glory, and he wanted his own glory. Other nations, in his view, should be proud to serve under his umbrella. That, he seemed to think, was recognition enough.

Churchill saw what Montgomery refused to see: the Empire was dying, and nations that once took orders now made choices. Canada’s independence was not a technical detail; it was the reason Canada was still in the war at all.

By the time Normandy began, the situation was close to a rupture.

On June 6th, 1944—D-Day—Canadian troops landed on Juno Beach. The sea was rough. The air was filled with the rattle of machine guns. Bullets stitched the surf. Men fell in shallow water, their blood mixing with salt. Yet the Canadians kept moving. They pushed through the beach defenses, climbed the seawall, and pressed inland with a determination that astonished even seasoned commanders.

By nightfall, Canadian forces had advanced deeper than any other Allied division—miles beyond the shoreline, liberating towns, fighting through villages where snipers hid in windows and German soldiers waited in cellars. In the first two days, Canadians liberated nearly twenty French towns. Their momentum was fierce.

And Montgomery’s first reports emphasized “British beaches secured,” vague enough to swallow Canadian achievements whole.

Then came Carpiquet. July 4th and 5th. The airfield mattered because whoever controlled it controlled approaches to Caen. The Germans defended it with the 12th SS Panzer Division—Hitler Youth—teenage soldiers hardened into fanatics. They had already murdered Canadian prisoners earlier in the campaign. Now they held hangars and control towers, determined to fight to the last.

Canadian soldiers entered those hangars like men stepping into another world. The buildings were enormous, metal walls echoing every shout, every blast. In the darkness, muzzle flashes lit faces for split seconds—faces young enough to belong in classrooms, not slaughterhouses. Grenades thundered. Bayonets flashed. The smell of blood and cordite thickened until breathing felt like swallowing iron.

Two days. Three hundred seventy-seven casualties.

But the Canadians took the airfield. They held it against counterattacks. They opened the route to Caen.

On July 6th, Montgomery held a press conference. War correspondents crowded under canvas, notebooks ready, eyes hungry for headlines. Montgomery stood straight in crisp uniform, confidence radiating from him like heat. He announced, “British forces have secured the position,” and spoke of tactics and timing and future plans.

He did not say “Canada” even once.

A Canadian correspondent in the tent—Ross Munro—had seen the dead carried from hangars. He had spoken with wounded men whose hands shook as they tried to light cigarettes with broken fingers. Now he listened to Montgomery erase them. That night, Munro wrote with restrained fury. His words traveled home. Canadian newspapers printed them. Canadians read them at breakfast tables beside casualty lists.

Two days later, Operation Charnwood began—July 8th and 9th. Canadian and British units attacked together. Canadian troops cleared fortified villages, house by house, grenade by grenade. SS troops fought from cellars and attics. Canadians lost over a thousand men in days. The casualty numbers mounted until they felt unreal, like a flood you could not stop.

Montgomery’s report to London spoke of “my forces” and “British infantry performed magnificently.” Canadian efforts appeared as a single sentence buried deep, almost like an afterthought.

In Ottawa, headlines erupted: Canadian blood, British glory. Questions sharpened into accusations. Why were Canadian boys dying for British press releases? Why did London take credit for Ottawa’s sacrifice? Opposition politicians demanded answers. Some even suggested withdrawing Canadian forces from Montgomery’s command.

Mackenzie King faced a political crisis he could not ignore. He could not pull Canada out of Normandy; the war had to be won. But he also could not tell Canadian families that their sons’ sacrifices would be recorded under someone else’s name.

On July 15th, King sent Churchill a telegram that was blunt. The failure to acknowledge Canadian sacrifices had become politically dangerous. He could not hold the line much longer without visible recognition.

Churchill received that message like a weight settling on his chest. This was exactly what he had feared: Montgomery’s vanity had become a strategic threat.

He decided he would not rely on secondhand assurances anymore. On July 18th, he requested Montgomery’s dispatches since D-Day for personal review. All of them. He would read every word himself.

Two days later, at Chequers—his country estate outside London—Churchill sat at a desk in morning light. His private secretary, John Colville, sat nearby with a notebook and pen, watching with the wary patience of a man who understood that history sometimes turned on tempers.

A stack of papers lay between them, thick as a brick. Six weeks of dispatches from France. Churchill picked up the first and began to read.

He took a red pencil. A mark for each mention of Canadian forces. A double mark when Canadians were credited as primary. An X when vague phrases like “British forces” appeared in actions Canadians had led.

The morning wore on. Churchill’s cigar burned down to ash; he lit another. Page after page, the pattern sharpened like a blade. Dozens of reports, only a handful naming Canadians. Victories described as British where Canadian casualties had been heaviest. Canadian blood turned into British ink.

Colville watched Churchill’s face redden, watched his jaw tighten, watched the pencil press harder into paper.

Then came Operation Atlantic—July 18th through 20th—fresh enough to sting. Canadian divisions had crossed the Orne River, pushed into industrial suburbs south of Caen, and faced three SS Panzer divisions. Fighting in factory buildings, tanks in narrow streets, artillery that never seemed to stop. Canadians advanced miles through fortified positions, destroyed German armor, captured prisoners, and suffered nearly two thousand casualties.

Montgomery’s preliminary report described it as a British Second Army success, with “Canadian support” reduced to a single sentence.

Something in Churchill snapped.

He threw the paper across the room. Colville flinched despite himself. Churchill stood so fast his chair toppled backward. He began pacing like a caged animal, hands trembling—not with fear, but rage.

Canadian boys were dying by the thousands. Mothers were getting telegrams. Fathers were losing sons. Sisters were losing brothers. And Montgomery was not only stealing credit; he was stealing the one thing the dead could still claim: the truth of what they had done.

Churchill’s voice rose, harsh and raw. Colville later admitted he dared not write down some of what was said. Not because it was unimportant, but because it was too fierce, too personal, too much like a man’s private grief exploding into politics.

When the storm of words ended, Churchill stopped pacing. He stood still, breathing hard, and his eyes had the cold clarity of a decision finalized.

He called for a secretary and a typewriter.

He would send Montgomery a personal telegram—directly, not filtered through polite bureaucracy. He began dictating with a voice that was iron now, controlled but deadly.

“Your recent dispatches display a troubling economy with the truth…”

He ordered that future reports must name Canadian units when they were the primary force. He demanded a public statement acknowledging Canadian contributions to date. He declared that a Canadian liaison officer would be assigned to Montgomery’s headquarters to review public communications before release. And then he struck the heart of it:

“I have assured Mr. King that Canada’s contributions would be properly acknowledged. Your vanity makes me a liar.”

When Churchill signed that telegram, he signed it with more than ink. He signed it with Britain’s future.

Montgomery replied the next day. Colville brought the response at breakfast. Churchill read it while his eggs cooled, and the temperature in the room dropped.

Montgomery’s reply was defensive, even petulant. He claimed standard military practice. He argued that as commander of British Commonwealth forces, he could refer to them as British. He called the issue “colonial sensitivities.”

Colonial sensitivities.

Churchill’s hand crushed the telegram into a ball. Canada was not a colony. Canadians were not subjects. They were volunteers—free people who had chosen to fight.

Montgomery’s words did not merely miss the point; they insulted it.

Churchill dictated a second message at once, short and lethal in its simplicity.

“You command Canadian forces because Canada has generously placed them under British command. They remain Canadian, not British. They can be withdrawn if you cannot grasp this distinction. Canadians are not colonials. They are volunteers.”

It was, for a man like Montgomery, a threat that reached straight into the engine of his ambition. His command—and his legacy—depended on political support. If he wrecked the Canadian alliance, no popularity at home would save him.

This time, Montgomery’s response arrived quickly. Brief. Obedient. He would issue a public statement acknowledging Canadian contributions. Future dispatches would properly identify national units. He would cooperate with the liaison officer.

No argument. No lecture. Just compliance.

Churchill read it with grim satisfaction, but there was no joy in the victory. The truth that lingered bitterly was that Britain’s most successful general had needed to be threatened into showing basic respect to Britain’s most loyal ally. It was a symptom of a larger illness: the Empire’s old arrogance, lingering even as the world changed.

On July 23rd, 1944, Montgomery stood before war correspondents at his headquarters in France—tents and vehicles hidden in an orchard, flies buzzing in summer heat, diesel and canvas in the air. He wore his crisp uniform and famous beret. Normally he enjoyed these briefings; they were stages, and he was always ready to play the hero.

But today his jaw was clenched. His face looked tight, like a man swallowing something bitter.

He held a prepared statement and read it in a flat voice, acknowledging the exceptional contributions of Canadian formations. He admitted the Canadians’ deep advance from Juno Beach. He spoke of Canadian tenacity around Caen. He praised their courage as equal to any force under his command.

To Canadian journalists listening, it was almost surreal—like watching a stubborn man finally say the words everyone knew were true.

In Canada, the statement landed like a thunderclap. Newspapers that had been boiling for weeks splashed it across front pages. Radio stations read the words aloud again and again. Canadian families heard, at last, their sons’ efforts named properly in the mouth of the high command.

In Ottawa, the political pressure eased almost overnight. Mackenzie King’s crisis evaporated. Opposition voices quieted. Pride replaced fury—though grief remained, because no statement could resurrect the dead.

At the front, Canadian soldiers were more cynical. They had seen too much to be impressed by speeches. One private wrote home with dry humor: “Monty finally remembered we exist. Took Churchill twisting his arm.” For many, recognition was nice, but it did not change what they were there to do: finish the job and go home. Still, something shifted. It mattered to know their nation would not be erased in someone else’s story.

The consequences went beyond feelings. On that same day—July 23rd—First Canadian Army became operational under General Harry Crerar. The timing was not accidental. It was a message carved into organization: Canadians would not be swallowed by vague labels anymore. They would be distinct, undeniable. A nation fighting under its own name.

As the summer of 1944 turned toward autumn, First Canadian Army grew into one of the largest fighting forces in Western Europe. Hundreds of thousands served under the Canadian flag. Montgomery still commanded the broader army group, but now Canada’s identity was formal, structural, visible.

And the first great test came in August at the Falaise Gap.

German forces were trapped in a pocket south of Caen. The Allies closed in like a tightening noose. First Canadian Army held the northern jaw of the trap, tasked with pushing south to link with Americans coming north. If they succeeded, they could destroy a major German army in France.

The fighting was desperate. Germans tried to break out. Tanks clashed across fields. Artillery turned the landscape into a cratered nightmare. The summer heat made the smell of death unbearable. Bodies of men and horses lay in the sun. The noise of battle never stopped. Yet Canadian forces pressed forward, losing thousands but holding their line. When the gap finally closed, tens of thousands of Germans surrendered, and the German military power in France cracked.

This time Montgomery’s dispatches told the truth. He credited First Canadian Army clearly, admitting the destruction of German forces owed primarily to Canadian determination and sacrifice. The words were now correct, because Churchill had made correctness non-negotiable.

The autumn brought another Canadian ordeal: the Scheldt estuary.

Antwerp—captured intact—could have transformed Allied logistics, but access to the port was blocked by German-held islands and flooded lowlands. The terrain was a nightmare of mud, water, and cold. Canadian soldiers fought in waist-deep floods. October rains soaked them to the bone. Men developed trench foot. Hypothermia stalked the trenches. German defenders fought savagely because they understood what Antwerp meant.

For six weeks, Canadians fought through misery and fire, taking ground yard by yard. Casualties climbed into the tens of thousands. But they cleared the Scheldt. They opened the port. Supplies could finally flow close to the front lines, fueling the final push into Germany. Military historians would later call it a decisive logistical victory—and it had been paid for largely in Canadian blood.

Now, in dispatch after dispatch, Canada was named.

Recognition did not heal wounds, but it changed the way a nation carried them. It meant Canadian families could read the truth. It meant the dead would not be filed away under someone else’s banner.

In 1945, Canadian soldiers fought again through brutal conditions—operations that dragged them through forests turned to mud by thawing ground, through villages defended as if every house were a castle. Casualties mounted. But Canadians reached objectives that mattered strategically, drawing German reserves, shaping the final collapse. They fought, they bled, and now they were recorded properly as doing so.

By the time Germany surrendered in May 1945, Canada’s wartime record was astonishing. From a small peacetime force, Canada had built military power that fought across multiple theaters. More than a million Canadians served in uniform. Tens of thousands died; many more were wounded. The cost, per capita, was immense. In proportion to their numbers, Canadians had paid dearly.

Churchill never publicly boasted about his confrontation with Montgomery. He understood the need to keep Allied unity looking smooth from the outside. The public saw photos of Churchill and Montgomery together, hands clasped, smiles fixed, as if politics were always friendly.

But in private, Churchill admitted to Mackenzie King that he regretted not acting sooner. That recognition should have been automatic and that needing intervention at the highest level was itself a failure.

Montgomery, for his part, never truly forgave the humiliation. In later memoirs, he still minimized Canadian contributions, burying them where he could. Some Canadian veterans remembered him with cold politeness—a general of skill, yes, but also a man who had tried to write them out of their own war until forced to stop.

Yet the shift Churchill demanded outlasted the personalities.

Coalition warfare after 1944 learned a lesson: alliances were not held together by maps and tactics alone. They were held together by respect, and respect included truth. Who fought mattered. Who died mattered. Names mattered.

In Canada, the episode became part of a larger national coming-of-age. Canadians did not fight for recognition, as the soldiers themselves often said. They fought because it was right. But a nation’s sacrifice deserved to be remembered accurately, not smudged into another nation’s narrative. The dead could not argue with press releases. Someone had to speak for them.

Churchill had understood that.

And because he did—because he was willing to confront even his most successful commander to protect an ally’s dignity—the story of Normandy would not be written with Canadian names missing, or Canadian grief dismissed as “sensitivities.” It would be written with the truth, harsh and costly and real: that Canadian forces had shouldered some of the hardest fighting in France, that they had paid for victory in blood, and that their sacrifices were not a footnote to British success but a central pillar of it.

Years later, visitors would walk through Normandy and see Canadian memorials standing in fields where men had fallen. They would stand at cemeteries where rows of headstones stretched under wide skies. They would see maple leaves carved into stone and read words promising the dead would not be forgotten.

Once, in July 1944, there had been a real danger they might be—erased not by enemy fire, but by the quiet theft of credit.

Churchill’s fury in a smoke-filled room in London had helped prevent that.

In war, battles are fought with bullets and tanks. But sometimes the battles that decide the shape of history are fought with words—one word in a dispatch, one name spoken aloud, one correction forced onto the record.

“Canadian,” not “British.”

A distinction that seems small until you imagine the telegram arriving at a farmhouse in Saskatchewan or a flat in Montreal, and a mother reading it with shaking hands.

Because for those families, and for those men who stormed hangars and streets and flooded fields, the truth was not politics.

It was the last thing the living could give the dead.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.