The Echoes of ’71: Why Soldiers Killed Officers as War Ended

October 12th, 1971. The jungle is quiet, too quiet for a war zone, but loud with the friction of men who have stopped believing in the mission. Inside a sandbagged bunker, the air is thick with humidity and the stale smell of cigarette smoke. First Sergeant William Pace does not sleep. He lies awake on his cot, staring at the corrugated tin roof, listening to the footsteps outside.

He is not listening for the North Vietnamese army. He is listening for the sound of a safety lever pinging off the spoon of an M26 fragmentation grenade. Outside, in the sprawling chaos of the firebase, a group of 19-year-old drafties sits in the dark. They are smoking Ojiua cigarettes laced with heroin. They are not cleaning their rifles.

They are not checking the perimeter wire. They are voting. The topic on the ballot is not political. It is visceral. It is a referendum on survival. They are debating whether the first sergeant lives to see the sunrise. The consensus is building. He is a lifer. He is gung-ho. He wants to run patrols. He wants to engage the enemy. And in late 1971, that is a capital offense.

This is not a scene from a movie about prison gangs. This is the United States Army in the final spasms of the Vietnam War. The pin is pulled, the spoon flies off, the fuse burns for 4 seconds. Boom. The explosion shreds the command bunker. It is loud, violent, and anonymous. When the dust settles and the medics rush in, there is no enemy to pursue. The jungle is empty.

The killer is standing in the formation the next morning, answering here at roll call, eyes flat, face blank. The official report will likely list the incident as accidental discharge or combat related. But everyone knows, the officers know, the NCOs’s know, and the men know. This was a fragging.

Between 1969 and 1972, the US Army did not just fight the Vietkong and the North Vietnamese. It fought itself. The Pentagon confirmed over 800 attempts to murder superiors with explosive devices. The actual number, buried under vague reports and terrified silence, is likely double or triple that figure. It was a breakdown of discipline so severe, so systemic that it threatened to destroy the American military from the inside out.

It was the sound of an army collapsing under the weight of a war that had lost its meaning. We are going to walk you through the disintegration. We will take you into the bunkers where the bounties were collected. We will examine the mechanics of the M26 grenade, the weapon of choice for the disgruntled grunt.

We will look at the map of South Vietnam as it shrank from a theater of war into a series of isolated, paranoid enclaves. and we will answer the question that haunted every lieutenant who stepped off a chopper in 1971. How do you lead men who are ready to kill you to avoid a fight? To understand the fragging epidemic, you have to understand the time and the place.

You have to understand the specific suffocating atmosphere of Vietnam in 1971. Zoom out. Look at the strategic map. It is no longer 1965. The days of search and destroy, of massive air cavalry assaults, of the belief that American firepower could grind the enemy into dust, are gone. The Ted offensive of 1968 broke the political will of the United States.

President Richard Nixon has entered the White House with a promise. Peace with honor, Vietnamization. The plan is simple on paper. Hand the war over to the South Vietnamese Army, the ARVN, and bring the American boys home. The troop levels tell the story. In 1969, there were over 540,000 American troops in country.

By the end of 1971, that number has plummeted to 156,000. Every week, thousands of men board the freedom birds, the commercial airliners chartered to take them back to the world. The giant bases at Long Bin and Daang are being dismantled, stripped of their equipment, turned over to the locals. But the war is not over. And that is the crux of the horror.

For the 156,000 men left behind, the war has entered a grotesque zombie phase. The objective is no longer to win. The objective is to leave. But until you leave, you still have to patrol. You still have to man the bunkers. You still have to walk into the ambush zones. Imagine you are a 20-year-old drafty from Detroit or De Moines.

You did not volunteer. You do not want to be here. You read the newspapers from back home or the underground GI sheets that circulate in the barracks. You know the country has turned against the war. You know the politicians are negotiating the exit. You know with absolute certainty that the piece of ground you are standing on today will be abandoned tomorrow.

And then your lieutenant, a 22-year-old ROC graduate who just arrived in country and needs a combat action badge to promote his career, orders you to walk down a trail known to be rigged with booby traps. He wants to capture a hill that has no strategic value. He wants a body count.

He is asking you to be the last man to die for a mistake. This is the friction point. This is where the spark hits the gasoline. In previous wars, soldiers fought for territory, for victory, or for the survival of their unit. In 1971, Vietnam, the primary motivation for the infantrymen is simply to survive his 365day tour.

Short, that is the religion. How short are you? How many days left? A soldier with 30 days left is a ghost. He is practically gone. He is riskaverse to the point of mutiny. Into this volatile mix steps the officer core. And here we must make a critical distinction. We are not talking about the beloved leaders, the men who respected their troops and prioritized survival.

We are talking about the lifers. The term lifer is thrown around with venom in 1971. It refers to the career soldiers, the NCOs and officers who view the army as a profession, not a prison sentence. To the drafty, the lifer is the enemy. The lifer cares about shine on boots in the middle of monsoon mud. The lifer cares about haircut regulations when there is no clean water.

The lifer cares about contact with the enemy because contact brings medals and medals bring promotion. The disconnect is total. The army’s rotation policy exacerbates it. An enlisted man serves 12 months in Vietnam. An officer serves 12 months, but only six of those are in command of a combat unit. The other six are spent in a staff job.

This means the officer is constantly new, constantly inexperienced, and constantly under pressure to prove himself in a very short window. He has 6 months to make a name for himself. He needs results. The drafty, who has been in the bush for 8 months, looks at this new lieutenant and sees a dangerous amateur. He sees a man who is going to get them all killed for a piece of ribbon.

The social contract of the military hierarchy dissolves. The mere [ __ ] rule, a cynical phrase used by lawyers and prosecutors, implies that killing a Vietnamese civilian is a minor crime. But now that lawlessness turns inward, if the rules of war don’t apply to the enemy, and they don’t apply to civilians, why do they apply to the sergeant who keeps screaming at you to dig a latrine in the rain? Discipline does not break down all at once.

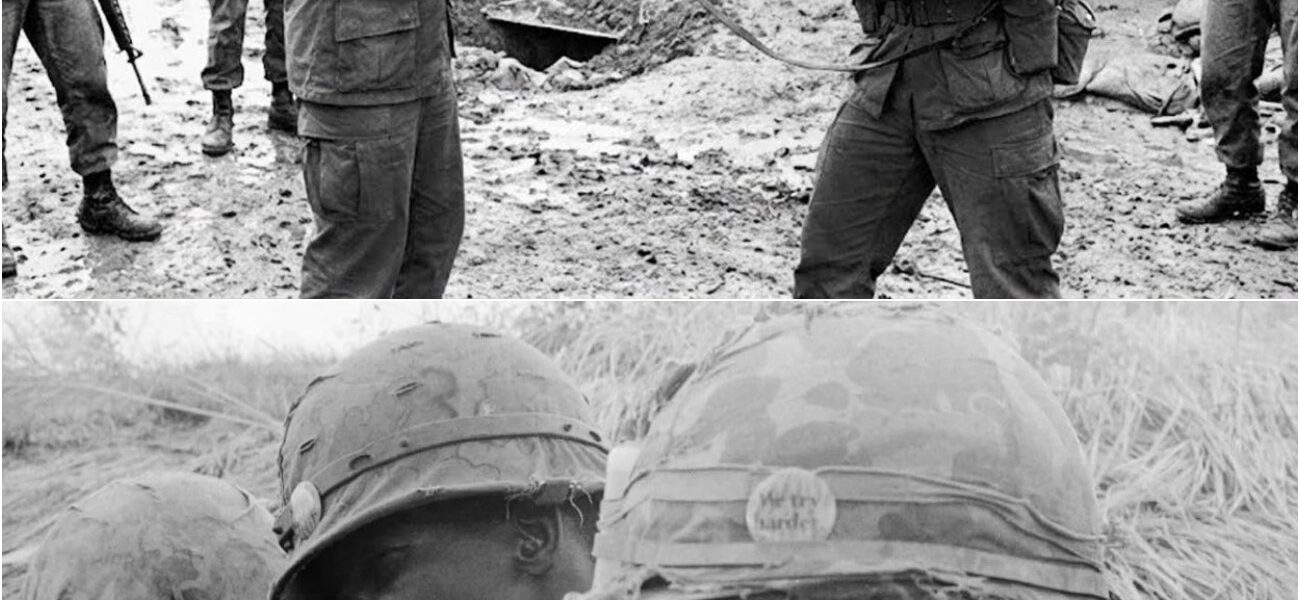

It erodess. It starts with the uniforms. By 1971, you see soldiers in the bush wearing peace medallions, love beads, and bandanas. You see slogans written on helmets, born to kill next to a peace sign, FTA, scrolled on flack jackets. The official meaning is fun, travel, adventure. The real meaning is the army.

It moves to the salute. In the rear areas, officers are ignored. In the bush, a salute is a sniper target, so it is forbidden. But the lack of respect goes deeper. It becomes a sullen refusal to acknowledge authority. Then comes the search and evade. A unit is ordered to patrol a specific grid square to find the enemy.

They leave the firebase, walk a few hundred meters into the thick jungle and stop. They find a shaded spot. They sit down. They smoke. They eat rations. They radio in false coordinates. Checkpoint alpha reached. No activity. They wait out the day, then return to base, reporting a quiet patrol. They have successfully avoided the war.

But what happens when the officer refuses to play along? What happens when you get a captain who insists on checking the coordinates? What happens when you get a sergeant who kicks the men awake and forces them into a firefight? That is when the rock appears. It is a warning. A simple rock perhaps wrapped in a rubber band thrown onto the officer’s bed while he is sleeping or a smoke grenade tossed into his hooch. It is a message.

You are pushing too hard. Back off. If the officer ignores the rock, the next message is the tear gas grenade. It makes his life miserable, burns his eyes, forces him out of his bunker. It is an escalation. We can get to you. If he still doesn’t get it, if he courts Marshall, a popular soldier, if he orders a suicidal assault, if he cracks down on the drug use, the final step is taken, the frag.

Let’s look at the weapon itself. The M26 fragmentation grenade. It is a lemon-shaped sphere of cast iron filled with composition B explosive. Inside the iron shell is a notched wire coil that shatters into hundreds of high velocity steel fragments upon detonation. It has a kill radius of 5 m and a casualty radius of 15. Why the grenade? Why not the M16 rifle? The rifle is personal.

It requires line of sight. It has a ballistic signature. If you shoot a captain in the back of the head, the bullet can be recovered. The rifling on the bullet can be matched to the barrel of your specific gun. It is murder, plain and simple, and you will go to Levvenworth for life. The grenade is impersonal. It is anonymous.

It destroys the evidence of its own identity. When it explodes, the spoon and the pin are left behind, but if the thrower is careful, those are nowhere near the scene. The fragments that kill the officer are generic steel shards. They cannot be traced to any specific solders’s inventory. Anyone could have thrown it. The enemy uses grenades.

Maybe it was a sapper. Maybe it was a booby trap. Maybe it was an accident. And the grenade allows for distance. You can pull the pin, hold the lever, lob it into a bunker, and be back in your own cot, pretending to sleep before the 4-se secondond fuse burns down. You don’t have to look the man in the eye when he dies.

It is the perfect weapon for a crime that requires deniability. The prevalence of weaponry in 1971 Vietnam is staggering. A soldier can acquire almost anything. Grenades are not carefully accounted for in the heat of a combat zone. They are expended on patrols. A soldier can claim he threw two grenades at a suspected noise in the bush and no one will question him.

He pockets them instead. But it wasn’t just grenades. The creativity of the violence is chilling. Claymore mines were turned around to face the command post. C4 plastic explosive was molded into the hollow legs of bunk beds. Sugar was poured into the gas tanks of jeeps to seize the engines, but the grenade remained the symbol.

It gave the phenomenon its name, fragging. The statistics we have are the tip of the iceberg. The Pentagon reported 126 incidents in 1969. In 1970, that number jumped to 271. In 1971, it hit 333. But these are only the ones that involved an explosive device and a clear target. It does not count the combat accidents.

It does not count the officer who was shot in the back during a firefight. It does not count the medic who failed to reach the wounded NCO in time. The environment in which this happens is a pressure cooker of boredom, fear, and intoxication. By 1971, the American army in Vietnam is a wash in drugs. Marijuana is ubiquitous.

It is sold in sandwich bags for $5. It is smoked through shotgun barrels. But the real game changer is heroin. High-grade white heroin, widely available in Southeast Asia, hits the barracks. It is cheap, it is pure, and it is 95% addictive. By some estimates, 10 to 15% of the lower ranking enlisted men are users. The drug numbs the fear.

It numbs the boredom, but it also detaches the user from reality. It erodess moral inhibitions. A junkie who is high or crashing from a high is volatile. When an officer tries to bust a drug ring or confiscate the stash, he is not just enforcing discipline. He is threatening the soldier’s chemical lifeline. Consider the demographics.

The army of 1971 is a draft army. The average age is 19. These men are products of the late 1960s in America. They have seen the riots in Detroit and Newark. They have seen the protests on college campuses. They have heard the black power rhetoric. They have listened to rock and roll that challenges the establishment.

They do not trust the man. And in Vietnam, the man is the captain with the map. Race plays a massive jagged role in this story. The racial tension in the US military in 1971 is at a boiling point. Black soldiers, disproportionately drafted and often assigned to the most dangerous combat roles are organizing. They wear DAP cords on their wrists.

They greet each other with elaborate handshakes, the DAP, which can take minutes to complete. To the white officers, this is a sign of a secret society. It is threatening. In the rear areas, there are race riots. At Cameron Bay, at Daang, white and black soldiers fight with chains and knives. Confederate flags fly over some hooches.

Black power flags fly over others. When a white officer disciplines a black soldier, it is often perceived as racially motivated. The retaliation can be lethal. But fragging was not strictly a racial issue. It was a class issue. It was the grunts versus the lifers. It was the oppressed versus the oppressors. It was a labor dispute resolved with high explosives.

Let’s zoom into a specific location to see how this dynamic breathes. Take fire support base Maranne, March 1971. FSB Maryanne is located in Quangin Province. It is an isolated hilltop protecting nothing in particular. Garrisoned by men of the American division. The America has a bad reputation. It is the division of my lie. Discipline is loose.

The base is sloppy. The perimeter wire is not maintained. The guards are often stoned. The NCOs’s and officers who try to tighten up the security are met with sullen resistance. The men just want to be left alone. They feel abandoned by their country. Why should they maintain the wire? The war is over, isn’t it? The tragedy of Maryanne is usually remembered for the sapper attack that overran the base, killing 30 Americans.

But the investigation revealed the rot underneath. The officers were afraid of their men. There were reports of fragging threats prior to the attack. The breakdown in the chain of command meant that when the enemy finally did come, the unit was paralyzed. They had spent so much time fighting each other, they had forgotten how to fight the North Vietnamese. This is the context.

This is the setup. A shrinking army, a losing war, a drug epidemic, a racial crisis, and a rotation policy that puts ambitious amateurs in charge of disillusioned survivors. But to truly understand the horror, we have to look at the money. Yes, money. Fragging was not always a crime of passion. Sometimes it was a business transaction.

In the darkest corners of the base camps, in the back of the enlisted clubs, there were pools, bounties. A soldier would put up $50. Another would match it. The pot would grow $500, $1,000, a price on the head of a sergeant or a lieutenant. The first man to grease the top sergeant gets the pot. It sounds like fiction.

It sounds like something out of a dystopian novel. But the C, the Criminal Investigation Division, found evidence of these pools. They found notices in the underground newspapers. A reward is offered for the neutralization of Captain X. This is the system turning predatory. It is the ultimate inversion of the military ethos.

The band of brothers has become a murder conspiracy. The investigative files from 1971 are filled with surreal testimonies. Soldiers admitting that they didn’t hate the officer personally, but the unit had decided he was dangerous. It was a democratic decision, a vote. He’s going to get us killed. Therefore, he has to go.

It was seen as self-defense, preemptive self-defense, and the officers knew it. Imagine being a captain in 1971. You walk past a group of your own men. They stop talking. They look at you. You see the hatred in their eyes. You enter your bunker at night. You check the corners. You check under your mattress. You lock the door, something you never had to do in previous wars.

You sleep with your 45 caliber pistol cocked and locked under your pillow. You are not afraid of the Vietkong sapper crawling through the wire. You are afraid of the kid from Ohio who served you lunch in the messaul. This fear changed the way the war was fought. It paralyzed the army. Officers stopped giving orders. They stopped correcting uniforms.

They stopped enforcing drug laws. They negotiated with their men. If you guys go out on this patrol, we won’t go far. We’ll just go to the treeine and sit. It was a mutiny in slow motion, a negotiation of terms. The officer kept his life and the men kept their safety. And the war, the war became a charade. We need to talk about the rear echelon.

The dynamic there was different but just as deadly. In the huge bases like Long Bin, boredom was the enemy. Men had access to alcohol, drugs, and weapons, but no enemy to fight. The aggression turned inward. In the rear, fragging was often about petty grievances. A sergeant puts a soldier on KP duty too many times. Boom.

A lieutenant denies a pass to go to Saigon. Boom. The threshold for violence had lowered so much that lethal force became the response to minor irritations. The value of human life had been devalued by years of body counts and free fire zones. If the army treated people like numbers, the soldiers would do the same.

The military justice system was overwhelmed. How do you investigate a fragging? The scene is destroyed. The witnesses are silent. The unit closes ranks. I didn’t see anything, sir. I was asleep. The investigators were often threatened themselves. You better watch your step or you’ll be next. So, few were caught, and those who were caught often received light sentences.

The army didn’t want to publicize the scale of the problem. A high-profile trial would only prove to the American public that the military had lost control. So, they pleaded cases down. They discharged men as unfit. They shipped the problem home. This brings us to the pivotal moment, the shift from anecdotal horror to systemic crisis.

Senator Mike Mansfield, the Senate Majority Leader, speaks out. He calls the reports of fragging the most tragic and sorrowful chapter in the history of the American military. The press picks it up. Time magazine runs a cover story. The secret is out. The parents of the drafties read the stories. They are terrified. Their sons are not just in danger from the communists.

They are in danger from their own platoon mates or worse, their sons might be the killers. The army leadership in the Pentagon is in a panic. General West Morland, now the chief of staff, is receiving daily reports of serious incidents. He realizes that the army is not just losing the war, it is losing its soul. If the chain of command breaks, there is no army, there is just an armed mob.

And in 1971, in the valleys of the central highlands and the fire bases of the DMZ, the mob is armed with automatic weapons and M26 grenades. Let’s return to the bunker, to the silence after the explosion. The dust clears. The medics carry the body away. The men go back to their hooches. The sun comes up.

The war goes on. But it is a different war. It is a war of shadows and side glances. In the next section, we will delve deeper into the specific stories. We will look at the trial of Private Billy Dean Smith, accused of fragging his officers. We will examine the psychological profile of the fragger.

And we will show you how the drug culture and the anti-war movement intersected to create a perfect storm of rebellion. We have established the scene. The powder keg is full. The fuse is burning. Now we watch it explode. March 15th, 1971. Bian Hoa air base. The heat is already rising off the tarmac, distorting the air, making the distant hangers shimmer like a mirage.

Bian Hoa is not the jungle. It is a sprawling industrial complex of war. It smells of JP4 jet fuel, burning latrine waste, and the exhaust of 10,000 trucks. It is supposed to be safe. It is supposed to be the rear. But at 0 hours, safety is an illusion. Inside the officer’s billets of the second battalion, 7th cavalry, the air conditioning units are humming, masking the sound of footsteps outside.

Two lieutenants are sleeping. First lieutenant Richard E. Stander and First Lieutenant Thomas A. Delmano. They are young. They are administrative. They are not leading charges up Hamburger Hill. They are managing logistics. A shadow moves near the window. A screen is cut. A hand reaches in. But this time, something goes wrong.

The grenade hits the screen or bounces. The fuse hisses. The explosion tears through the wall, shattering the night. Both men are wounded but alive. Wait, that was just the prologue. 1 hour later, same night, same base, different hooch. First Lieutenant Vincent Taco and First Lieutenant Paul Holton are asleep in their quarters.

They are popular enough, or so they think. They are not screaming tyrants. They are just officers. the symbols of the machine. The killer has reloaded. This time there is no mistake. A fragmentation grenade sails through the opening. The blast is contained within the small room. The physics of a grenade in a confined space are merciless.

The over pressure wave alone is lethal. The shrapnel is secondary. Teo and Holton are dead before the smoke clears. This double murder at Bhoa becomes the lightning rod. It is not just another statistic. It is the beginning of the Billy Dean Smith affair, a legal and cultural firestorm that will expose the deepest fractures in the US Army.

Billy Dean Smith is a 22-year-old private. He is black. He is vocal. He is what the command calls a troublemaker and what his peers call a man of conscience. He has written letters home complaining about the harassment of black soldiers. He has been cited for insubordination, the catch-all charge for any soldier who doesn’t lower his eyes when spoken to.

When the CD, Criminal Investigation Division, arrives at the scene, they are under immense pressure. The brass wants a culprit. They want a narrative that explains this violence as the act of a single deranged radical, not a symptom of a broken system. They zero in on Smith. They find a grenade pin in his pocket.

It seems like a smoking gun, but in Vietnam in 1971, a grenade pin is common currency. Soldiers use them as roach clips for marijuana joints. They wear them on their bush hats. They use them to clean their fingernails. Possession of a pin proves nothing other than that Smith is a soldier in Vietnam. The trial of Billy Dean Smith becomes a spectacle.

It is moved to the United States to Fort, California. It becomes a proxy war for the racial tensions simmering in every platoon from the Delta to the DMZ. The prosecution paints Smith as a militant, a black power advocate who hates white authority. The defense paints him as a scapegoat, a man framed by a command structure terrified of its own troops.

Spoiler alert, Smith is acquitted. The evidence is flimsy. The grenade pin matches nothing. The witnesses contradict each other, but the aqu quiddle does not heal the wound. It tears it open. It confirms to the enlisted men that the army is out to get them. It confirms to the officers that they can be murdered with impunity and the killer will walk free.

This case forces us to look at the investigator’s dilemma. How do you solve a crime where everyone is armed and everyone is a suspect? Picture a C agent arriving at a fire base after a fragging. He is a warrant officer, maybe 30 years old. He steps off the chopper into a hostile world. The unit has closed ranks.

This is the code of silence, stronger than the mafia’s oma. The agent asks, “Who did this?” The men reply, “It was a sapper, sir. We saw a shadow in the wire.” The agent points to the blast pattern, which clearly shows the grenade was thrown from inside the perimeter from the direction of the enlisted bunkers. The men shrug.

Sappers are sneaky, sir. They are mocking him. They are holding weapons. They are high on something that dilates their pupils. The agent knows that if he pushes too hard, if he threatens the wrong man, he might not make it back to the landing zone. The investigation is often prefuncter. Photos are taken.

Statements are typed up. The conclusion is unsolved. But why the rage? Why the lethal intensity? We have to look at the changing face of the NCO corps. In 1965, the non-commissioned officer, the sergeant, was the backbone of the army. He was a woou or Korea veteran. He was 35 years old. He was a father figure.

He was tough, but he knew how to keep men alive. He knew the difference between a necessary risk and a foolish one. By 1971, those men are gone. They have retired, or they have been killed, or they have rotated home and refused to come back. The army desperate for leaders creates the instant NCO, the shake and bake. A shake and bake sergeant is a kid.

He is selected in basic training because he scored high on a test. He is sent to a 12week NCO school. He is given stripes and a pay raise. He is sent to Vietnam. He is 19 years old. He has zero combat experience. He steps off the plane and is put in charge of a squad of hardened veterans who have been in the bush for 10 months. Imagine the dynamic.

You are a grunt. You have survived ambushes, booby traps, and malaria. You know which trails to avoid. You know the sound of an AK-47 safety clicking off. And suddenly, a teenager with fresh stripes and a rulebook tells you to walk down a trail that smells of trouble. He tells you to dig a foxhole according to the manual, not according to the terrain.

He threatens to write you up for not wearing your flack jacket in 100° heat. He is dangerous. He is a liability. The veterans test him. They ignore his orders. They laugh at him. If he backs down and learns from them, he survives. He becomes one of the guys. But if he asserts his authority, if he tries to be the lifer he was trained to be, he puts a target on his back.

The friction is not just about competence. It is about the fundamental purpose of the war. By 1971, the search and destroy strategy has mutated into something the troops call search and avoid. This is a critical tactical shift that explains the rise in violence against officers. The soldiers have developed a sophisticated system of non-engagement.

It is an unwritten treaty with the enemy. Here is how it works. A platoon is ordered to patrol a sector. They move out. They go one kilometer. They find a thick patch of jungle. They stop. They set up a perimeter and they sit. This is called sandbagging. The radio man calls in false reports. HQ, this is Alpha 2.

Approaching checkpoint delta. Heavy vegetation. Slowgoing. Roger. Alpha 2. Continue mission. 2 hours later. HQ, this is Alpha 2. We are at the objective. Negative contact. Setting up night ambush. In reality, they haven’t moved. They are eating peaches from seration cans. They are reading paperbacks. They are sleeping.

The Vietkong often know this. They watch the Americans sit. As long as the Americans don’t attack, the VC don’t attack. It is a live and let live stalemate. Both sides are waiting for the Americans to go home. But then comes the officer who breaks the treaty. Maybe it’s a new captain eager for a body count.

Body count is the metric of success in Vietnam. It is the only way to measure progress in a war without front lines. Promotions are tied to it. RNR passes are tied to it. This captain looks at the map. He looks at the lack of contact. He gets suspicious. He decides to lead the patrol himself. He forces the men to get up.

He forces them to march into the known enemy sanctuaries. He forces them to engage. He is breaking the truce. He is inviting death and the men respond with the logic of survival. If we go up that hill, three of us will die. If we frag the captain, one of us goes to jail maybe and zero of us die. It is a cold utilitarian calculus.

Let’s look at the numbers again. The breakdown of fragging incidents by rank. Over 50% of the victims were officers, lieutenants, and captains. Over 40% were NCOs, sergeants. The rest were others, sometimes fellow soldiers who were seen as informants or snitches. The concentration of violence against junior officers, lieutenants, is telling.

They were the point of contact. They were the ones issuing the direct orders. The colonel back at the firebase was hated, but he was out of range. The lieutenant was right there sleeping in the next hammock. Now we must layer in the chemical accelerant, heroin. In late 1970, a new type of heroin appeared in Saigon.

They called it number four. It was 90 to 98% pure white powder. In the US, street heroin was maybe 5% pure. This stuff was militaryra narcotic. You didn’t need a needle. You could smoke it. You could snort it. It came in plastic vials or small plastic bags. It cost$ two or three dollars a hit.

That’s the price of a pack of cigarettes. The addiction rate skyrocketed. The Department of Defense estimated that by 1971 nearly 30,000 servicemen in Vietnam were addicts. That is two full combat divisions of junkies. A soldier on heroin is a ghost. He is checked out. He doesn’t care about the war. He doesn’t care about his uniform.

He cares about the next vial. When an officer tries to intervene, he is interfering with a physiological need. The withdrawal symptoms of number four are horrific. Vomiting, cramps, hallucinations, terror. A soldier facing withdrawal is a desperate animal. If his sergeant tries to confiscate his stash, that sergeant is not an authority figure.

He is a torturer. The fragging incidents involving drugs are often the most brutal. There is no political statement involved. It is pure reactive rage. One documented case, a sergeant finds a stash of heroin in a bunker. He flushes it. That night, a claymore mine is detonated under his floorboards. The men didn’t just want him dead.

They wanted him obliterated. They wanted to send a message to the next sergeant. Look the other way. This creates a zone of immunity within the units. Certain bunkers become no-go zones for officers. The heads drug users congregate there. They have their own hierarchy. They have their own weapons. An officer enters at his own risk. If he is smart, he knocks.

If he is smart, he ignores the smell of opium. If he is stupid, he kicks down the door. And in 1971, stupid officers didn’t last long. But we must also look at the juicers, the alcoholics. The cultural divide in the platoon often split between the heads, pot heroin users, usually younger, more anti-establishment, and the juicers, alcohol drinkers, usually older, more traditional, often the NCOs’s.

The heads and the juicers hated each other. The juicers saw the heads as undisiplined hippies who were ruining the army. The heads saw the juicers as aggressive drunks who were perpetuating the war. Violence flared between these groups. A fragging wasn’t always vertical. soldier versus officer. Sometimes it was horizontal, a grenade thrown into a bunker of heads by a discussed juicer or vice versa.

It was a civil war within the platoon. Let’s introduce a specific voice here to ground this. SP4 Robert Example Jenkins, a composite of typical testimonies from the era, grounded in reality. Jenkins is a 20-year-old drafty in the 101st Airborne. It is July 1971. He is at Camp Eagle. You got to understand, he says, looking at the interviewer, eyes hollow.

We aren’t fighting the NBA anymore. We’re fighting the clock. I got 42 days in a wakeup. You think I’m going to walk point? You think I’m going to let some lieutenant from Georgia who thinks he’s John Wayne get me zipped up in a body bag? No way, man. No way. If he pushes it, he pays. We had a pool going for our co 300 bucks.

Nobody collected it cuz he got transferred. But we were ready. We were all ready. This readiness is key. It wasn’t just the psychopaths. It was the good soldiers, too. The moral compass had shifted. The definition of enemy had shifted. The enemy is the person trying to get you killed. If that person wears an NVA uniform, you shoot him.

If that person wears US Army green, you frag him. Survival is the only morality left. The geography of the fragging is also important. It happened most often in the rear or at the static fire bases. In the deep bush, in the middle of a firefight, the officer and the men needed each other.

The bond of combat survival still held. You don’t kill the man calling in the air strikes when you are being overrun. But back at the base, when the adrenaline fades, when the boredom sets in, that is when the grievances fester. That is when the rock gets thrown. The army tried to adapt. They created rap sessions.

This was a desperate attempt to bridge the gap. Officers and enlisted men would sit in a circle without rank insignia and talk it out. Picture it. A humid tent. 20 sullen gis sitting on folding chairs. A nervous major standing at a whiteboard. Men, let’s talk about racial harmony. Let’s talk about our feelings.

The men look at him with contempt. They don’t want to talk about feelings. They want to know why they are still in Vietnam. When the president says the war is ending, they want to know why the stake in the officer’s mess is real and the meat in their chow line is mystery gray. The rap sessions often devolved into shouting matches or stoned silence.

They were a band-aid on a gunshot wound and all the while the withdrawal continues. The standown of units one by one, the colors are cased. The first infantry division goes home. The Marines go home. The ninth division goes home. The men left behind feel like the rejects, the forgotten. Why us? Why are we the last ones? This feeling of being the garbage left to rot creates a nihilism that fuels the violence.

If nobody cares about us, why should we care about the rules? We see the rise of the combat refusal. This is the prelude to fragging. October 1971. Firebase pace again. The same place we started. A company of the first cavalry division is ordered to go out on a night ambush. Six men say no. Not I can’t but I won’t.

This is mutiny. Under the uniform code of military justice. This is punishable by death in theory or long imprisonment. But the captain doesn’t arrest them. He can’t. If he arrests them, the whole company might revolt. He negotiates. He pleads. Eventually, he sends a different squad. The story leaks to the press.

A journalist is there. The world hears that American soldiers are refusing to fight. This humiliates the army, but it saves the captain’s life. He chose compromise over fragging. Those who didn’t compromise became the statistics. Let’s look at the medical data. The wounds from a fragging are distinctive. Dr.

David Example Jones, a surgeon at the 95th Evacuation Hospital in Daang, 1971. You can tell a fragging victim, he notes. The wounds are all lower body, legs, groin, abdomen. The grenade rolls on the floor. It explodes upward. It’s nasty. It mims more often than it kills. We see guys with their legs shredded, but their faces untouched.

They wake up in the posttop and they know. They don’t ask what happened. They ask who. The survivors are shipped home. They carry the physical scars, but also the psychological trauma of betrayal. They were not wounded by the communists. They were wounded by the kid who slept three bunks down.

This betrayal rots the soul of the officer corps. It creates a generation of leaders who are cynical, paranoid, and deeply distrustful of the draft. It is no coincidence that after Vietnam, the US Army moves to an allv volunteer force. The draft was deemed unmanageable. The conscript army had fired its own officers. The experiment was over.

But in 1971, the experiment is still dying its slow, violent death. We have to mention the bounty hunters, the rumors of hitmen. There were stories, never fully confirmed, but widely believed, of soldiers who would frag an officer for a price, even if they weren’t in the unit. A transaction, I’ll do yours if you do mine. Strangers on a train, Vietnam style.

The breakdown is total. The machine is eating itself. In the next section, we will zoom out to the climax. We will look at how the Pentagon finally reacted. The massive crackdown, the drug tests, the sudden acceleration of the withdrawal because the army simply could not function anymore. And we will deliver the thesis. The war didn’t just end because of politics or protests.

It ended because the US army physically ceased to be an obedient instrument of state power. The soldiers voted with their grenades and the vote was no. September 1971, Tanute Air Base, the gateway to Vietnam and the gateway out. But now the exit has a toll booth. General Kraton Abrams, the commander of MACV, has received a direct order from the White House.

The president is not just worried about the war being lost. He is worried about the army coming home. He is terrified that the addiction epidemic in the jungle is about to become an addiction epidemic on the streets of America. So the order goes out. Operation Golden Flow. It is a humiliation on an industrial scale.

Before any soldier can board the Freedom Bird to fly back to the United States, he must provide a urine sample. He must prove he is clean. Imagine the scene. A hanger filled with hundreds of men. They are exhausted. They have survived 12 months of patrols, ambushes, and boredom. They are hours away from civilization.

And now they stand in long lines holding plastic bottles watched by NCOs’s whose sole job is to stare at genitalia to ensure no one is switching samples. If the sample turns the chemistry purple, you don’t go home. You go to detox. You are quarantined. You are stripped of your dignity and treated not as a veteran but as a junkie.

This policy intended to solve the drug problem pours gasoline on the fire of resentment. It creates a new class of prisoner. The soldier who has served his time but cannot leave. It creates a desperate market for clean urine. Non-users sell their urine to addicts for $50 a pint. Soldiers carry hidden bladders of clean pee inside their pants.

The Golden Flow sums up the relationship between the army and its men in late 1971. Mutual suspicion, invasive control, total lack of trust. The army is now fighting a two-front war. To the west, the North Vietnamese. To the rear, its own troops. And the resources required to fight the internal war are draining the combat strength. Military police units are doubled.

Drug suppression teams are formed. Officers are pulled from combat command to run amnesty programs. The bureaucracy of discipline is consuming the bureaucracy of war. Let’s look at the data of disintegration. In 1971, the US Army in Vietnam records 5,000 admissions for drug treatment. In the same year, there are over 10,000 incidents of insubordination or mutiny.

The desertion rate hits an all-time high. 73.5 desertions per 1,000 soldiers. That means in every battalion of 1,000 men, nearly 75 will simply walk away. They disappear into the slums of Saigon or Cholon, living in the sole alley districts, protected by Vietnamese girlfriends or criminal gangs. But the most dangerous place is not the alley.

It is the stockade, the long bin jail, the LBJ. If you want to see the future of the American collapse, look inside the wire of the LBJ in 1971. It is designed to hold 1500 prisoners. By mid1971, it holds nearly double that. These are not PS. These are American soldiers, murderers, rapists, drug dealers, but mostly men who refuse to follow orders.

The racial segregation inside the LBJ is absolute. The blacks control certain cell blocks. The whites control others. The guards are terrified to enter the compounds at night. There are riots that last for days. In 1968, there was a major riot at LBJ that left a chaotic burn scar on the facility. By 1971, the tension is constant.

It is a pressure cooker. This racial polarization in the jails reflects the polarization in the field, and it feeds the fragging epidemic. When a black soldier feels targeted by a white officer, singled out for haircut violations or DAP greetings or given the most dangerous point position on patrol, he does not see it as military discipline.

He sees it as a continuation of the oppression he left back in Memphis or Chicago. The rhetoric of the black power movement has permeated the barracks. No Vietnamese ever called me. That isn’t just a slogan. It is a worldview. Why fight a brown man in Asia for a white man who oppresses you in Alabama? When this worldview collides with a lifer officer who demands traditional subservience, the result is violence.

We see a shift in the type of fragging. Early in the war, fragging was tactical. You killed an incompetent leader to save your life in combat. By late 1971, fragging is often political or retaliatory. You kill a leader because he is a racist or because he is a tyrant or simply because he represents the system. The sympathetic detonation.

This is a phenomenon where one fragging inspires another. A unit hears that alpha company greased their captain. The idea is planted. It becomes a viable option. It becomes a contagion. The army tries to counter this with intelligence. They try to spy on their own men. Enter the plant. C agents are dressed as privates and sent into units to identify the drug.

The drug dealers and the fraggers. They are told to blend in, grow their hair long, use the slang, buy the drugs. But the grunts are not stupid. They are hypervigilant survivors. They spot the plants. Hey, new guy, you ask too many questions. Hey, new guy, your boots are too new. Hey, new guy. You don’t have the thousandy stare.

The life expectancy of a known snitch in 1971 is measured in hours. If a soldier is suspected of being an informant, he doesn’t get a warning rock. He gets a grenade immediately. The violence against informants is ruthless. There is a documented case near Daang where a soldier suspected of snitching was found dead.

Not from a grenade, from a mechanical ambush. A claymore mine rig normally used against the VC set up inside the latrine block. It was an execution. This paranoia destroys unit cohesion. Nobody talks. Nobody trusts the new guy. The band of brothers is replaced by a collection of isolated clicks. The heads, the brothers, the juicers, the lifers, and the enemy is watching.

The North Vietnamese army, NVA, and the Vietkong are well aware of the American disintegration. Their propaganda broadcasts, Radio Hanoi, play the latest rock music. They read the names of American units. They say, “Gis, why die for Nixon? Frag your officer and go home.” They drop leaflets in the jungle.

Don’t fire at us and we won’t fire at you. This reinforces the search and evade tactic. The NVA allows the Americans to survive as long as the Americans remain passive. It is a psychological operation of genius. By removing the immediate threat of death, they remove the justification for the American officer’s aggression. If the enemy isn’t shooting, why is the captain making us patrol? The captain becomes the only source of danger.

He is the only one breaking the piece. Let’s zoom in on the mechanics of a specific unit breakdown. The 196th Light Infantry Brigade, 1971. This unit is the last combat brigade in Vietnam. They are the rear guard. They know they are the last ones out the door. The morale is subterranean. In August 1971, nearly 100 men of Delta Company refuse a direct order to patrol. They simply sit down.

The TV cameras are there. The commander pleads. The men are articulate. They are not screaming. They are reasoning. It makes no sense, sir. We are leaving in a month. Why get killed today? The command is paralyzed. If they court marshall 100 men, they lose the company. If they shoot them, they have a massacre on national television. So they blink.

The men are reassigned. The patrol is cancelled. The lesson ripples through the entire army. You can say no. And if you can say no to a patrol, you can say no to anything. And if the officer doesn’t accept no, you have the grenade. The collapse of the judicial system is the final accelerant. In 1969, the conviction rate for fragging was low.

By 1971, it is almost non-existent for the actual murder charge. Witness intimidation is rampant. In one trial, a witness takes the stand. He looks at the accused who is sitting at the defense table. The accused runs a finger across his throat. The witness suddenly forgets everything. I don’t recall, sir.

It was dark. The judges and prosecutors are overwhelmed. They start offering plea bargains for aggravated assault or illegal possession of explosives just to get a conviction. A man who rolls a grenade into a hooch and mims a lieutenant might serve only 5 years or two. The disparity between the crime and the punishment shocks the officer corps.

A lieutenant writes home. They tried to kill me last night. They missed. The kid who did it is walking around the base today. I can’t prove it. My colonel says to let it go. Let it go. I sleep in a flack jacket. This is the moment of systemic failure when the state can no longer protect its own agents from its own citizens.

Let’s look at the equipment loss. It’s not just lives, it’s hardware. Sabotage becomes a daily routine. A truck driver doesn’t want to drive a convoy. He pours sugar in the tank. A mechanic doesn’t want to fix a helicopter. He accidentally strips a bolt. The deadline rates, the percentage of equipment that is broken, skyrocket.

Millions of dollars of equipment are written off as combat loss. When in reality, it was destroyed by bored, angry teenagers who just wanted to stop working. And amidst this chaos, the withdrawal schedule is accelerated. President Nixon announces another 45,000 troops will come home. The standown ceremonies are surreal.

A unit forms up on a parade ground. The flags are lowered. The speeches are made. You have served with honor. The men cheer. They throw their helmets in the air. They rip off their patches. They are not cheering for victory. They are cheering for survival. But for the units not yet stood down, the jealousy is poisonous. Why them and not us? The randomness of the exit fuels the nihilism.

You are not fighting for a cause. You are fighting a lottery. Let’s compare the fragging of 1971 to the mutiny of 1917 in the French army. In WWI, the French soldiers refused to attack. They stayed in the trenches. They said, “We will defend, but we will not die for nothing.” The generals executed them by the dozens to restore order.

In Vietnam 1971, the US Army cannot execute its own men. The political climate back home won’t allow it. The media is everywhere, so the mutiny succeeds. The army stops attacking. The dynamic defense strategy is implemented. This is Pentagon speak for retreat into the fire bases and prey. The fragging is the enforcement mechanism of this mutiny.

It is the soldier’s veto power. We must also consider the short timer’s fever. As a soldier gets closer to his darus date eligible for return from overseas, his behavior changes. At 100 days, he is cautious. At 30 days, he is paranoid. At seven days, he is useless. But in 1971, entire units are short. The whole army is short.

The institutional memory is gone. The NCOs’s who knew how to maintain discipline are gone. We are left with a hollow shell. And in this shell, the grenade is the ultimate arbiter. There is a terrifying intimacy to it. In a firefight, the enemy is a muzzle flash 200 m away. In a fragging, the enemy is the man who denies your leave request.

It shrinks the war down to the size of a platoon. The geopolitics of the Cold War vanish. It is just Hatfields and McCoys in Olive Drab. The bounty system we mentioned earlier evolves. It becomes sophisticated. We see evidence of pools that span across different units, a network of disgruntled soldiers sharing information.

Captain Smith is transferring to Alpha Company. Watch out for him. He’s a hard ass. The reputation precedes the officer. He arrives at his new command and the rock is already waiting on his pillow. He has been marked before he even issues an order. This is the democratization of violence. The hierarchy is inverted.

The lowest private holds the power of life and death over the highest fieldgrade officer, provided he has the nerve to pull the pin. By the end of 1971, the statistics are undeniable. 333 confirmed fragging incidents. Hundreds more suspected, 33 dead, hundreds maimed. But the real number is the prevented operations.

The patrols that never went out, the ambushes that were never set, the hills that were never taken. The American war effort has ceased to function, not because of enemy fire, but because of the friction of internal terror. We are approaching the end of the line. The narrative is about to close. The why has been answered. It wasn’t just madness.

It was a rational response to an irrational situation. The how has been detailed. The grenade, the drug, the racial divide. Now, in the final section, we must look at the legacy. How did the army survive this? What happened to the men who came home? And the final haunting question, did the fragging actually save lives by ending the war sooner? Did the mutiny force the politicians hand? The stage is set for the climax, the thesis confirmation.

The realization that the US Army in Vietnam didn’t lose, it quit. And it quit at the barrel of its own gun. January 1972. The Pentagon. A closed door briefing. The charts on the easel are not about enemy troop movements. They are about force integrity. General West Morland looks at the line graph. It is going vertical.

Heroin use up. Desertion up. Assaults on officers up. The conclusion is inescapable. The United States Army is not just in danger of losing a war. It is in danger of ceasing to exist as a disciplined fighting force. The fragging epidemic has achieved what the North Vietnamese army could not. It has broken the chain of command.

It is here in this quiet carpeted room that the true climax of the story occurs. The decision is made not to win but to salvage. The acceleration of the withdrawal is no longer just a political strategy to appease voters. It is a desperate survival measure for the institution itself. We have to get the army out of Vietnam before the army destroys itself.

Back in the jungle, the grim reaper effect takes hold. This is the final inversion of reality. In a normal war, you fear the enemy. In late Vietnam, the officer fears his own men and the men fear the officer. The enemy is almost an afterthought, a backdrop to the internal struggle. Consider the case of Lieutenant Colonel William Nol.

He is often cited as the last American combat casualty of the war, killed by artillery fire in 1973. He died a hero. But compare him to the hundreds of lieutenants who died in the dark, killed by M26 grenades thrown by Private First Class John Doe. Nol’s death was tragic but intelligible. It fit the narrative of war.

The fragging deaths were unintelligible. They were incoherent. They shattered the myth of the band of brothers. They revealed that when the purpose of the war evaporates, the social contract of the military evaporates with it. The climax is a realization. The fragging wasn’t a bug in the system. It was the system working under impossible stress.

When you take a conscript army, force it to fight a war it doesn’t believe in, under officers it doesn’t trust, for a goal that has been abandoned, violence is the only logical output. The grenade was the soldier’s way of voting no when the ballot box was 8,000 m away. The loop closes. We started with First Sergeant Pace in his bunker, waiting for the explosion.

Now we see the aftermath. The explosion happened, but it didn’t just destroy a bunker. It destroyed the draft. It destroyed the old army. The resolution unfolds in the years that follow. 1973. The last combat troops leave. The PS come home to parades, but the fraggers come home, too. They don’t get parades. They get dishonorable discharges.

They get addiction struggles. They get silence. The army purges its records. It tries to bury the shame. The fragging statistics are compartmentalized, hidden in obscure reports. Why? Because to admit the scale of the mutiny is to admit that the American soldier, the icon of World War II, the liberator of Europe, had turned into a cop killer in the jungle.

It is a cultural trauma too deep to face. But the consequences are written in the structure of the modern military. Why does the US have an all volunteer force today? Because of 1971, the generals looked at the broken discipline of the drafties and said, “Never again. We will never again take men who do not want to be there. We will never again give them grenades and expect them to obey.

” The professionalization of the military, the intense focus on NCO development, the strict zero tolerance drug policies. All of these are antibodies produced to fight the virus of 1971. We see the cultural memory fade, but the scars remain. Watch a movie like Platoon or Full Metal Jacket. The tension between the officer and the enlisted man is the central conflict.

This art didn’t come from nowhere. It came from the transcripts of the 333 murder trials. Let’s look at the final numbers. The thesis confirmation. The US Army in Vietnam suffered roughly 58,000 deaths. Estimates suggest that between 800 and 1,000 of those deaths were at the hands of their own men. That is nearly 2% of the total casualties.

In the Civil War, men were shot for desertion. In Wu, men were executed for cowardice. In Vietnam, men killed their leaders to avoid the fight. The difference is the why. In 1944, the soldier knew that if he didn’t take the hill, fascism might win. In 1971, the soldier knew that if he didn’t take the hill, nothing would change.

The map would remain the same. The politicians would still talk. The only thing that would change is that he would be dead. And so, he pulled the pin. The epilogue takes us to a quiet cemetery in the Midwest or the South. There is a headstone. Captain James Smith, Vietnam, 1971. The family believes he died in a mortar attack.

The official letter said, “Hostile action.” And in a way, it was true. The action was hostile. But the hostility didn’t come from the north. It came from the hooch next door. The killer is alive today. He is in his 70s. He is a grandfather. He watches the news. He sees modern wars. Does he regret it? We have very few confessions. The crime carries no statute of limitations for murder.

The silence holds. But in the anonymous interviews given to researchers decades later, the tone is rarely remorse. It is grim necessity. It was him or us. He was crazy. We just wanted to go home. This is the haunting legacy of the fragging epidemic. It forces us to ask a question we prefer to avoid. What happens when you push a human being beyond the limits of loyalty? What happens when the authority loses its moral legitimacy? The answer is found in the fragment patterns of the M26 grenade.

The war ended. The troops came home. The jungle grew back over the fire bases. The bunkers collapsed. But the echo of that explosion, the sound of an army at war with itself, still rings in the ears of the institution. It is the reason why when a sergeant today looks at his men, he doesn’t just see subordinates.

He sees the delicate fragile consent that allows him to lead. He knows deep down that authority is not given by rank. It is earned. And if it is abused, the price can be 4 seconds of fuse. April 1975, the fall of Saigon. The helicopters lift off the embassy roof. The chaos is televised. The North Vietnamese tanks crash through the gates of the presidential palace.

But the American army is already gone. It left years ago, broken, dispirited, and radically changed. The echoes of 71 are not the sounds of the NVA victory. They are the sounds of the silence in the barracks after the grenade goes off. The sound of men looking at each other, knowing what they did and knowing they will never speak of it again.

Not through victory, but through survival. Not through glory, but through mutiny. The soldiers of 1971 didn’t just survive the war, they ended

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.