- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- I Can’t Believe This!” Korean Women POWs Shocked to Visit US Cities Without Being Chained. VD

I Can’t Believe This!” Korean Women POWs Shocked to Visit US Cities Without Being Chained. VD

I Can’t Believe This!” Korean Women POWs Shocked to Visit US Cities Without Being Chained

The Truth in the Streets

The rain had finally stopped as 23-year-old Kim Sunja stepped off the military transport bus in downtown San Francisco on July 14th, 1951. Her hands instinctively moved to her wrists, rubbing the phantom sensation of shackles that had been removed just hours earlier. As a captured North Korean nurse who had served with communist forces, she had been prepared for torture, degradation, and likely execution at the hands of the American imperialists. Instead, she stood unrestrained on Market Street, surrounded by 13 other female prisoners of war, all equally bewildered by the absence of armed guards pointing weapons at their backs.

“This must be some kind of psychological torture,” she whispered to her companion, Lieutenant Park Minio. “They will let us see paradise before they execute us.”

But as the minutes passed and the American escort merely pointed out landmarks in broken Korean, the women exchanged confused glances.

What Sunja saw defied 23 years of indoctrination. As ordinary Americans—men, women, children of all ages—walked past without sparing the enemy prisoners a second glance, she felt a rising sense of disbelief. No one shouted slurs, threw objects, or demanded their punishment. Instead, the crowded street continued its normal rhythm, a display of wealth and abundance that seemed staged for their benefit.

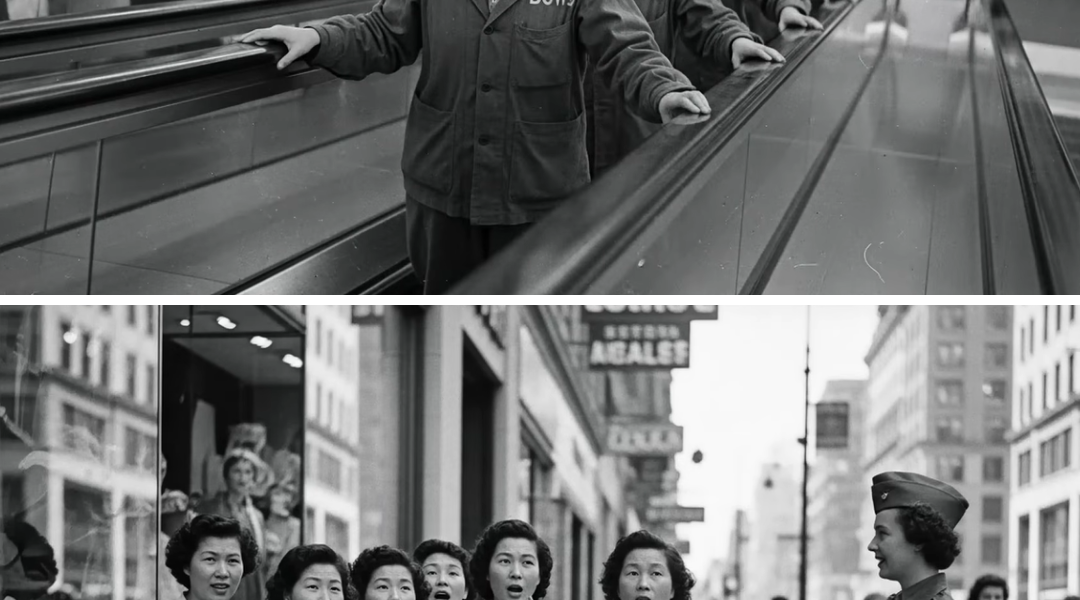

“Look at the shop windows,” gasped Corporal Lee G. Men, the youngest of their group at barely 19 years old. The displays featured mountains of fresh fruit, gleaming appliances, and racks of colorful clothing available apparently without ration cards or party connections. When their escort, Captain Margaret Wilson of the Women’s Army Corps, suggested they enter a department store, Sunja nearly refused, certain this was the moment they would be led to a basement for interrogation.

Instead, they rode a mechanical staircase to the second floor, where ordinary citizens, not party officials or military officers, were purchasing luxury goods with casual disregard for their value.

“How can there be so much?” Sunja asked Captain Wilson, gesturing toward a display of women’s shoes in more colors and styles than she had seen in her entire life.

“The war has been destroying America’s factories and cities,” Sunja continued. “Our leaders showed us the newsreels of your suffering.”

Captain Wilson’s bemused smile would become the first crack in the foundation of everything Sunja believed about the world beyond Korea’s borders. What happened next would shatter 23 years of indoctrination and transform not just Sunja’s understanding of America, but of her own nation, her leaders, and the very cause for which she had been willing to die.

The journey that brought Kim Sunja and her fellow prisoners to the streets of San Francisco began years earlier in the classrooms and propaganda halls of North Korea. From earliest childhood, Sunja had been taught that Americans were barbaric imperialists, whose technological advancement masked a morally bankrupt society built on exploitation and cruelty. The images from her textbooks remained vivid in her mind: American cities riddled with homeless beggars, workers chained to factory machines, and brutal police beating anyone who stepped out of line.

Most importantly, she had been taught that America’s apparent prosperity was a carefully constructed facade that concealed widespread poverty and oppression. According to her political education, America’s industrial capacity had been irreparably damaged during World War II, and what remained was dedicated solely to military production, leaving civilians to suffer. Statistics recited daily by her instructors claimed that 70% of Americans lived below subsistence level, that racial minorities were kept in conditions comparable to concentration camps, and that the average American worker earned barely enough for 500 grams of rice per day, less than the standard ration in North Korea.

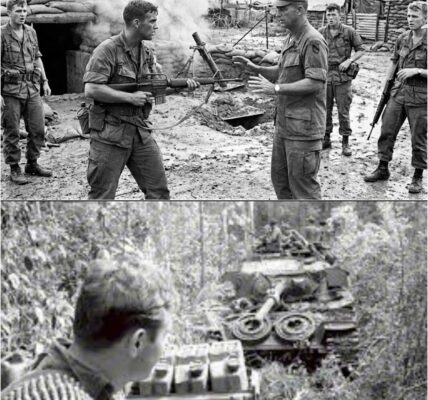

By 1950, when the Korean War erupted, Sunja had completed her nursing training and volunteered to serve with frontline units. Convinced she was defending her homeland against an aggressor whose society represented everything opposed to the workers’ paradise being built in the north under Supreme Leader Kim Il-sung, she joined the fight with complete faith in her cause.

When her field hospital was overrun near Taon in April 1951, she and the other captured medical personnel expected the worst. Tales of American atrocities—fingernails pulled out, prisoners forced to dig their own graves, women violated before execution—had been recounted so often that they seemed inevitable. Instead, they were processed through a series of prisoner-of-war camps. Each one progressively less restrictive until they reached a special compound on the outskirts of Seoul designated for female prisoners of war with medical training.

Here, American Women’s Army Corps officers informed them they had been selected for a cultural orientation program designed to prepare them for possible early repatriation as a goodwill gesture. None of the women believed this explanation. Clearly, they were being prepared for some sophisticated propaganda exercise. But the true scale of this orientation program would become apparent when, on July 10th, 1951, 14 women prisoners were loaded onto an American military transport aircraft. The first airplane any of them had ever seen up close, let alone boarded.

When Captain Wilson explained they were flying to the United States mainland, most assumed this was another lie or mistranslation. The 13-hour flight to Hawaii, followed by another 8 hours to California, marked the beginning of what military historians would later document as one of the most unusual psychological operations of the Korean conflict.

The program had been conceived by a forward-thinking Pentagon psychological operations specialist, Colonel James McKenzie, who had studied the impact of Japanese prisoners’ exposure to American life during World War II. He had documented how experiencing American abundance firsthand had fundamentally altered the worldview of many Japanese prisoners, creating valuable intelligence assets and potential post-war allies. With the Cold War intensifying, McKenzie proposed a similar, though more comprehensive program for select North Korean prisoners.

“Exposure to reality is more powerful than any interrogation technique,” McKenzie wrote in his classified proposal to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in February 1951. “A prisoner who has walked freely through an American supermarket becomes a permanently compromised ideological asset to the communist cause.”

Initially, McKenzie’s proposal had been rejected as too risky and expensive until intelligence reports revealed the particular vulnerability of North Korean female medical personnel, who possessed both valuable technical knowledge and significant influence in their communities. The 14 women selected for the program represented a cross-section of North Korean society. Kim Sunja was the daughter of a mid-level party official from Pyongyang. Park Minio came from a military family with revolutionary credentials dating back to the resistance against Japanese occupation. Lee Gman was a farmer’s daughter whose academic excellence had earned her rare advancement opportunities. Others included the niece of a provincial governor, the daughter of a factory manager, and several women from ordinary working backgrounds whose dedication to the party had enabled their medical training.

What united them was their absolute conviction in North Korean superiority and American depravity—beliefs about to be systematically dismantled by nothing more complicated than observation. Their first true shock came during the flight itself when they were served meals that included fresh fruit, white bread, and chocolate—luxury items most had not seen since before the war, if ever. More surprising was the casual manner in which leftover food was collected and discarded by the American crew. An act of waste that several women found more disturbing than anything they had witnessed on the battlefield.

“They throw away enough food to feed a family for days,” noted Huang Miqyouung, a 32-year-old senior nurse in a diary that would later become a valuable historical document. “At first, I thought this was a special display for our benefit, but the Americans seemed genuinely confused by our reaction when we asked to keep the uneaten portions. The young serviceman just shrugged and said, ‘There’s plenty more where that came from.’ This casual statement has troubled me more than any propaganda I have ever heard.”

Upon arrival at Travis Air Force Base in California, the women were processed through medical screening and provided with civilian clothing—another shock, as they had expected prison uniforms at best. The abundance of the base commissary, where ordinary servicemen purchased goods that would be considered extreme luxuries in North Korea, provided the first major cognitive challenge to their worldview.

“It cannot be real,” insisted Park Minio, the most ideologically committed of the group, as they were shown the shelves of food, personal items, and household goods. “This must be a special store for officers and party members.”

When Captain Wilson explained that similar stores existed on every American military installation worldwide and served everyone from generals to privates, Park refused to believe it. Her disbelief would require more substantial evidence. Evidence that the streets of San Francisco would soon provide in overwhelming abundance.

The decision to allow the prisoners to visit civilian areas represented a calculated risk by Colonel McKenzie’s team. Traditional security protocols would have kept enemy combatants confined to military installations, but McKenzie argued that the full psychological impact required immersion in normal American life.

“Restricted exposure creates skepticism,” he wrote. “Only unrestricted observation overwhelms ideological defenses.”

The women were transported in an unmarked bus accompanied by Korean-speaking WAC officers in civilian clothes and discrete military police several vehicles behind. A security detail the prisoners themselves never detected. The initial walk through downtown San Francisco on that July afternoon produced the first visible cracks in the women’s ideological armor.

The sheer number of automobiles—more than 6,000 passed them during their three-hour tour—contradicted specific propaganda they had been taught about America’s collapsed transportation infrastructure. The variety of foods available in shop windows, the multiple clothing stores with abundant inventory, and perhaps most significantly, the well-fed, well-dressed appearance of ordinary citizens, all directly challenged core beliefs about American society.

Sunja’s moment of truth came in a department store when Captain Wilson casually purchased hair ribbons for each of the women as souvenirs. The transaction took seconds, required no special permissions, no ration coupons, and no party membership verification. The ribbons, simple items that would have required saving for months in North Korea or connections to party officials, were treated as trivial purchases by the American officer.

“I keep touching the ribbon,” Sunja wrote that evening in notes she kept hidden inside her shoe. “It is made of real silk. In Pyongyang, such an item would be displayed in a glass case, available only to heroes of the revolution or the highest party officials. Captain Wilson bought 14 of them without hesitation, like buying a handful of rice.”

By the end of their 17-day journey, the women had witnessed enough to dismantle their ideological convictions. They had seen the waste, the abundance, and the freedom of choice that contradicted everything they had been taught about the capitalist world. And when they were asked about returning to North Korea, most chose to go back, not out of loyalty, but because they couldn’t bear the thought of abandoning their families and culture. Yet, in their hearts, they carried the truth they had learned—an unshakable truth that would live on long after their return.

Their experiences in America had planted a seed of doubt in the propaganda they had been fed their entire lives. And though they returned to a society where they could never speak of what they had witnessed, the truth could never be erased. It had been seen, felt, and remembered.

And sometimes, that’s all it takes to change the world.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.