Japanese POWs Were Shocked by American Breakfasts Bigger Than Dinner

The Breakfast of Defeat

In the misty dawn of December 7, 1943, Private Tō Fujiawa stood frozen in the mess hall doorway at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, his hands trembling around an aluminum tray laden with a feast that mocked everything he’d been taught. Three eggs, golden and perfect; four strips of crisp bacon; a towering stack of pancakes drenched in maple syrup; two slices of buttered toast; a bowl of oatmeal crowned with fresh fruit; and a tall glass of milk. It wasn’t just food—it was a revelation, a tangible slap against 14 years of imperial indoctrination. “This is for one person?” he whispered to the American guard, who nodded with casual indifference, as if abundance were as ordinary as breathing.

Tō’s eyes widened in disbelief. Around him, fellow prisoners—men who’d fought with fanatical devotion for the Emperor—received identical trays, their faces mirroring his shock. In that moment, the cracks began. If they fed even prisoners this way, he scribbled later in a hidden diary, Japan has been fighting a war it could never win. The meal wasn’t mere sustenance; it was evidence of an industrial might that dwarfed Japan’s disciplined austerity. Tō felt the first tremors of doubt, a seismic shift that would reshape not just his beliefs, but his nation’s future.

The journey to this shattering truth had begun years earlier, amid the fog of Japanese propaganda. In the 1930s and early 1940s, soldiers like Tō were steeped in tales of American weakness—a decadent giant, soft and corrupt, its people divided by race and greed, its factories inefficient, its soldiers lazy and ill-fed. Military manuals painted Americans as paper tigers, their abundance a facade masking imminent collapse. “They lack our spiritual fortitude,” instructors drilled. “Their diverse society breeds division; their Depression has crippled them forever.” Tō, a factory worker from Osaka drafted in 1942, believed it all. Japan, with its unified will, would crush this hollow foe.

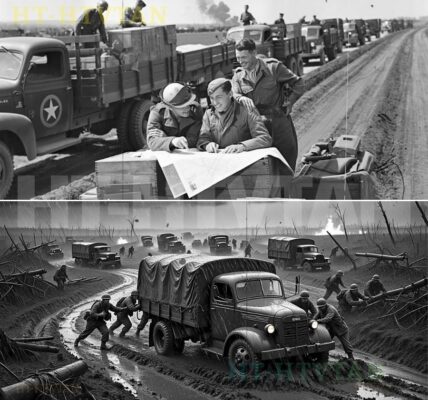

But reality unfolded differently. Japan’s gamble on a quick war—Pearl Harbor’s thunderclap meant to cripple American naval power—backfired spectacularly. Within months, the U.S. mobilized with breathtaking speed. Automobile plants morphed into tank factories; consumer goods vanished as resources poured into war. Yet civilians ate well, their larders full. By 1943, America churned out more equipment than all Axis powers combined: ships daily, 130,000 aircraft yearly. Japan managed a fraction. Tō and his comrades, captured in Pacific skirmishes, arrived convinced of victory. Instead, they boarded American transports, where rations shocked them anew.

Sergeant Hiroshi Nakamura, seized after Tarawa’s bloodbath in November 1943, recalled his first meal: “Enough for three men in my unit. I thought it a trick, but no—this was standard.” The K-ration for American troops brimmed with protein, chocolate, coffee, cigarettes—luxuries Japanese officers hoarded. Train rides across America unveiled vast farmlands, bustling cities, factories humming despite two years of war. Former Lieutenant Shigaru Yamamoto pressed his face to the window: “Fields of crops, cattle grazing… enough to feed an empire. They told us America starved, yet here it was.”

At camps like McCoy, Livingston, and Shelby, the abundance intensified. Prisoners got 4,000 calories daily—double a Japanese soldier’s ration, quadruple a civilian’s. Breakfasts mirrored Tō’s: eggs, bacon, toast, oatmeal, juice. Lunches featured beef stew, vegetables, pie; dinners, chicken, potatoes, cake. Captain Toshio Takahashi, a Guadalcanal physician at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, documented it clinically: “140 grams of protein daily—four times Japan’s. Sugar, unobtainable at home. 4,100 calories for labor.” Many prisoners suspected deception, whispering that real Americans starved, these feasts from dwindling stockpiles. Some refused extras, fearing lowered guards. But denial crumbled.

Clothing issued—three sets of work gear, coats, boots—stunned them. Wool and cotton surpassed Japan’s wartime blends of paper and bark. Lieutenant Ichiro Watanabe, captured in the Marshalls, hid shirt buttons like treasures: “They laughed, showed drawers full. ‘Take what you want.’ I didn’t sleep, pondering their capacity.” Medical care revealed more. Japanese soldiers endured untreated ailments; here, dentists fixed teeth in sessions, using tools unseen. Sergeant Kenji Miyazaki marveled: “Every American soldier gets this. Everything we knew was a lie.”

Camp life exposed broader truths. Newspapers and radios contradicted propaganda: American women, far from decadent, riveted ships and assembled planes as Rosie the Riveter. Hollywood films showed refrigerators stocked, homes electrified—luxuries in Japan. Prisoners worked farms, witnessing mechanization: one American farmer matching dozens of Japanese laborers. Warehouse duties revealed forklifts loading pallets in minutes, what took days for 50 men. Sergeant Takishi Kamura, in Texas, testified: “More canned goods in a day than my division ate monthly. Thousands of sites, endless supplies.”

By mid-1944, tours of factories hammered home the disparity. At Shelby, prisoners saw Ford plants churning engines—more monthly than Japan’s total. Captain Hiroshi Nakamura, an engineer, wrote: “They revealed it openly. Why hide? The gulf was too vast.” Oil derricks pumped freely in Louisiana; synthetic rubber flowed from labs. Waste shocked: scraps fed livestock, boots tossed for minor tears. “In Japan, we’d repair until rags,” Private Toshio lamented.

Psychologically, the toll mounted. Prisoners gained 22 pounds average, healthier as captives than soldiers. Ideological walls crumbled. Unlike defiant German POWs, Japanese abandoned imperial dogma. Requests for propaganda dwindled; English lessons surged. Lieutenant Colonel Hiroshi Abi confessed: “We expected barbarity, found humanity and strength. How deny it?”

Personal stories underscored the shift. Private Ichiro Yamada, from Osaka, arrived believing Japan victorious. His censored letters hinted at truth: “Americans eat meat daily, butter with every meal. I’m warmer, better fed as prisoner.” Guilt gnawed—families starved on 1,500 calories, rice mixed with sawdust. Sergeant Masaharu Takahashi wrote: “I live too well, thinking of your sacrifices.” Many turned to education, learning American methods for post-war Japan.

American guards, embodying quiet strength, treated prisoners humanely—firm yet fair, their discipline a model of resolve. These soldiers, drawn from farms and factories, fought with one hand while sustaining abundance with the other. Their generosity, born of a prosperous society, eroded enemy resolve without a shot. Tō admired their unassuming valor, the way they shared plenty without arrogance, proving might through deeds, not boasts.

By 1945, bombing reports confirmed the inevitable. Atomic blasts on Hiroshima and Nagasaki sealed it. Captain Toshio Yoshida reflected: “Conventional power alone could have razed Japan. This new weapon? Mere excess of capability.” Prisoners, transformed, focused on reconstruction.

Repatriated in 1946-47, they carried lessons home. Ichiro Nakamura, back in Nagoya’s ruins, became an agricultural official, urging mechanization: “One American tractor equals 20 farmers. Learn or starve.” Teeshi Kimura, a logistics whiz at Toyota, adopted U.S. systems: “Standardized, efficient—helped us compete.” Japan’s miracle—2,400 calories by 1960, Western breakfasts by 1980—owed partly to these men.

Tō, returning to Yokohama, opened a restaurant serving Western breakfasts. In 1972, he mused: “That tray showed American excess, but it was Japan’s future. Abundance, once shocking, became ours.” The breakfast of defeat birthed a new dawn, where material truth conquered ideology, and former foes shared prosperity’s feast. In those heartland camps, beliefs shattered, but hope endured—proof that even in war’s shadow, humanity’s bounty could illuminate the path to peace.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.