What Patton Did After a German Commander Said “You’ll Have to Kill Me”?

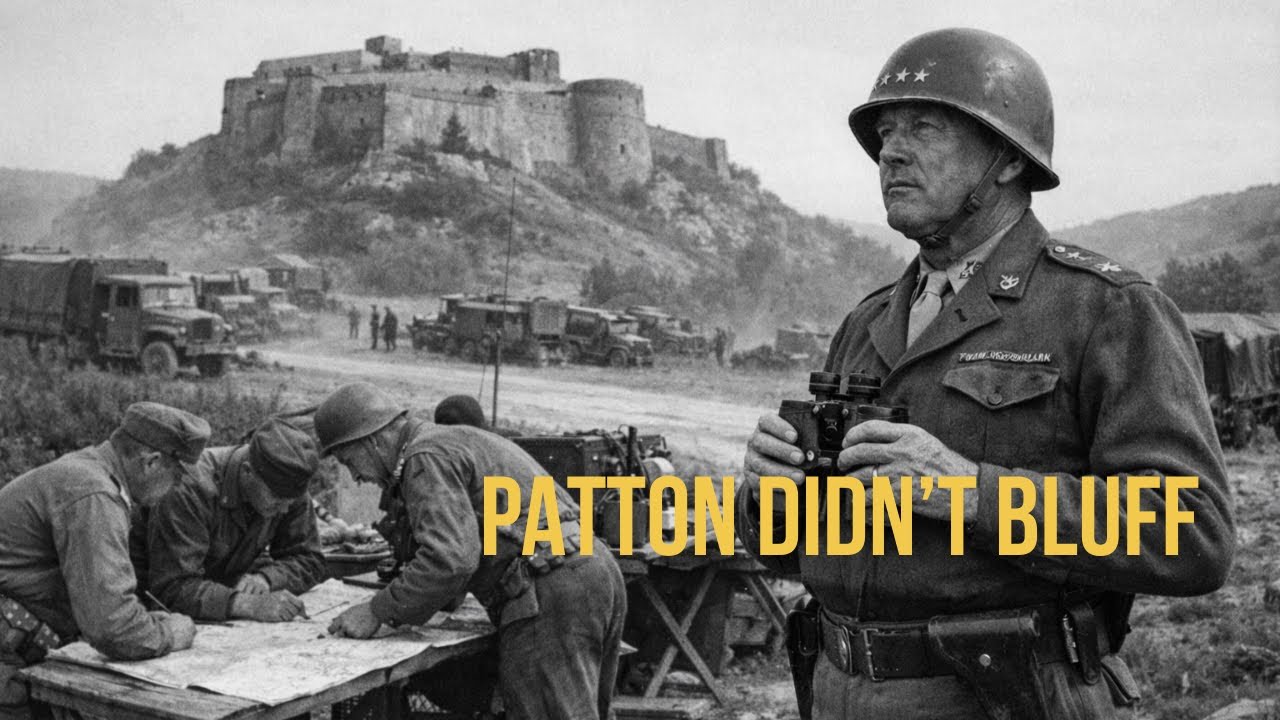

The fortress sat like a clenched fist on the hillside above the crossroads. Its thick stone walls built by French military engineers in the previous century when such structures still made strategic sense. September 1944 had brought the American Third Army racing across France with such velocity that German commanders found themselves trapped in positions they’d never intended to defend, making desperate stands at places whose names they couldn’t properly pronounce.

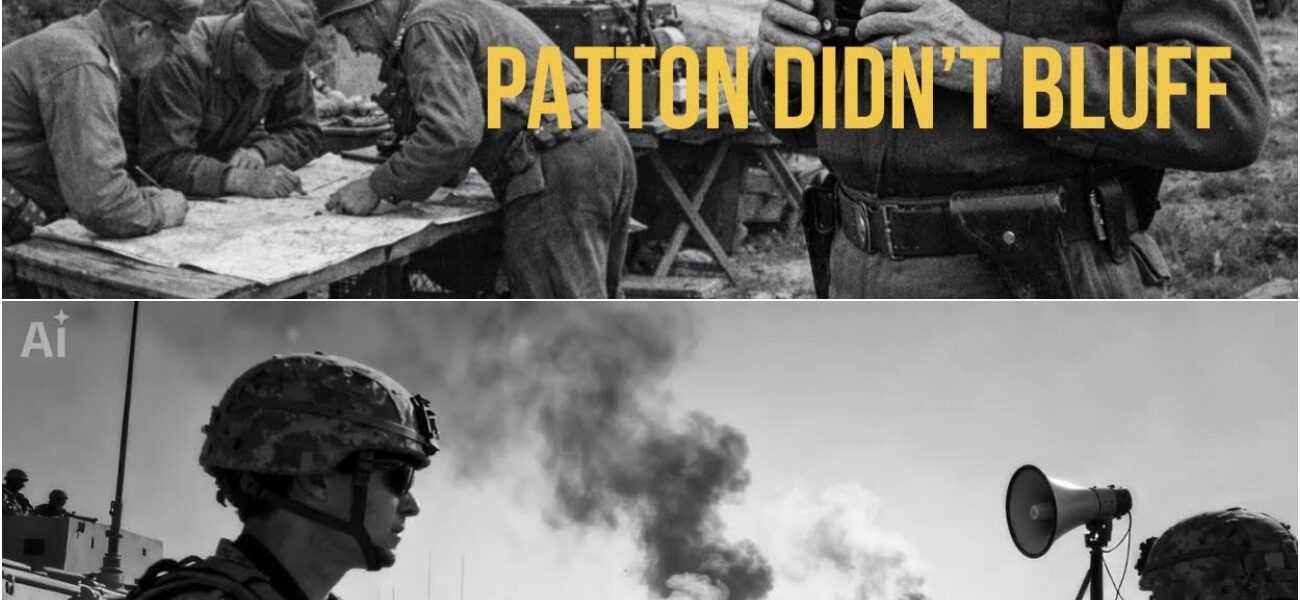

This particular fortress controlled a road junction that General George S. Patton needed for his supply lines. And the German major commanding 1,500 troops inside had just made a decision that would define the final hours of his life. The morning had begun with standard procedure. Patton always offered surrender terms first, not from sentiment, but from cold calculation.

A surrendered position cost zero American casualties, consumed zero ammunition, and wasted zero time. His staff had grown accustomed to this pattern. Send forward an officer under white flag present terms that were reasonable by any military standard and wait for the inevitable acceptance. Most German commanders in September 1944 understood the mathematics of their situation.

The war was lost. Fighting accomplished nothing except adding names to casualty lists. Surrender meant survival, prison camps, and eventual return home. When the madness ended, the major commanding the fortress apparently subscribed to different mathematics. When the American captain returned from delivering the surrender terms, his face carried an expression that made Patton staff officers exchange glances.

The captain saluted, cleared his throat, and delivered the German commander’s response word for word. as protocol demanded. The major had listened to the terms, considered them for perhaps 30 seconds, and then issued his reply with the formal precision of a man making an official declaration. Tell General Patton that if he wants this fortress, he will have to kill me to get it.

The staff officers waited for the explosion. Patton’s temper was legendary, his profanity creative, his rage when challenged something that could strip paint from walls. Instead, he stood silent for a moment, studying the fortress through his binoculars, his jaw working as he processed the information. When he lowered the binoculars and turned to his staff, his voice carried no anger, no frustration, no emotion whatsoever.

Four words delivered with the flat certainty of a man stating an obvious fact. I can arrange that.” The shock rippled through the command post. Officers who had served with Patton for years recognized this tone, and it unsettled them more than any display of temper would have. This was Patton in his most dangerous mode when he stopped being a personality and became a mechanism, a force of nature that would accomplish its objective with the same indifference a river shows when removing an obstacle from its path.

Fortress itself represented formidable defensive engineering. Its walls stood 3 m thick at the base, constructed from local stone that had weathered centuries without significant deterioration. The French builders had positioned it to command the high ground, giving defenders clear fields of fire in every direction.

Anyone approaching would climb exposed slopes under observation and direct fire from protected positions. The interior contained underground chambers for ammunition storage, a wellproviding independent water supply and reinforced positions that could withstand anything short of heavy artillery. Under competent command with adequate supplies, such a fortress could hold out for weeks, perhaps months.

Intelligence reports on the German major painted a picture of a career officer, 42 years old, decorated in the previous war, a professional soldier who had spent his adult life in military service. He had commanded the fortress for 6 weeks, arriving after the Normandy breakout when German forces were frantically trying to establish defensive lines that might slow the Allied advance.

His troops were a mixed collection. Some veteran infantry, some rerealon personnel pressed into combat roles, some very young soldiers who had completed basic training only weeks before. The major had worked methodically to prepare the position, stockpulling ammunition, organizing defensive sectors, drilling his men on fields of fire and fallback positions.

By all accounts, he was competent, thorough, and utterly committed to the increasingly abstract concept of duty that kept German forces fighting long after any rational hope of victory had evaporated. His motivations remained opaque. Perhaps he believed the propaganda about wonder weapons that would reverse the war’s trajectory.

Perhaps he feared the consequences of surrender more than the consequences of fighting. Perhaps he simply couldn’t conceive of any alternative to following orders, even orders that made no strategic sense. Or perhaps most tragically, he had internalized the notion that a soldier’s honor required fighting to the death regardless of circumstances.

that surrender represented a moral failure worse than pointless death. Whatever drove his decision, it transformed him from a problem to be solved into a target to be eliminated. Patton’s staff had expected orders to bypass the fortress, to leave a containing force and continue the advance. The Third Army’s momentum was its greatest asset.

Stopping to reduce every strong point would slow the entire offensive, but Patton had made his calculation instantly. The fortress controlled roads he needed. Bypassing it meant leaving enemy forces a stride his supply lines. The major had stated his terms clearly. You will have to kill me. Very well. Patton would take him at his word and fulfill his stated preference with maximum efficiency.

The transformation from negotiation to methodical planning took less than an hour. Staff officers gathered around maps as Patton outlined his approach with the precision of a surgeon describing an operation. No anger, no dramatics, just professional military planning applied to a straightforward problem.

The major says we have to kill him, Patton observed matterof factly. Let’s not disappoint him. The battle plan emerged in four distinct phases. First, complete encirclement. Every road, every trail, every possible escape route would be sealed. No resupply, no reinforcement, no retreat. The fortress would become an island, isolated and alone.

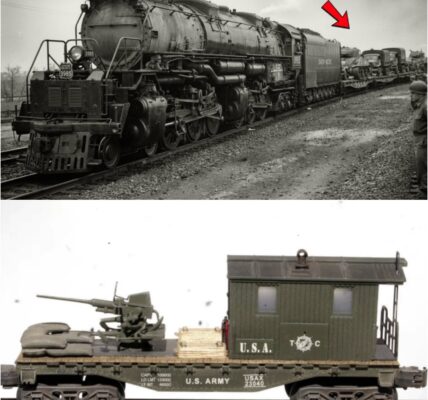

Second, artillery coordination. Every heavy gun within range would be registered on specific targets, wall sections, defensive positions, observation posts, the command bunker. Third, air support. Tank busting aircraft would conduct surgical strikes on command posts and ammunition storage. The kind of precision work that P47 Thunderbolts had perfected over months of combat.

Fourth and most unusual psychological warfare. Loudspeakers would broadcast the attack schedule hours in advance, giving every German soldier time to contemplate his commander’s decision and consider whether dying for a lost cause represented duty or stupidity. This final element revealed Patton’s understanding of human nature.

Professional soldiers could endure almost anything if it came as a surprise. if adrenaline and training took over before conscious thought could intervene. But knowing exactly what was coming, having hours to imagine the shells falling and the walls collapsing, that corroded morale more effectively than any bombardment.

The major had made his decision. His troops would have time to question whether they shared his commitment to death over surrender. Patton’s command philosophy rejected the notion that casualties were inevitable or acceptable. He believed in overwhelming force applied briefly and decisively in making the enemy’s position so untenable that resistance became obviously feudal.

Better to expend ammunition than lives. better to demonstrate irresistible power than to engage in prolonged fighting. His critics called him casualty indifferent, but the statistics told a different story. Third army units consistently suffered lower casualty rates than comparable formations because Patton refused to accept fair fights.

He created unfair fights, situations where American firepower was so overwhelming that German resistance collapsed quickly. As night fell, the encirclement was complete. Artillery batteries had registered their targets, firing ranging shots that the Germans could hear impacting around the fortress.

Aircraft had conducted reconnaissance flights, photographing every defensive position. Loudspeakers crackled to life, broadcasting in German. The assault will begin at dawn. You have been ordered to fight by your commander. General Patton will honor that order. Any soldier who wishes to surrender may do so at any time. Your commander has chosen death.

You may choose differently. Inside the fortress, the German major faced his own calculations. His defiant message had been a statement of principle, perhaps an attempt to inspire his troops, possibly a genuine expression of his willingness to die rather than surrender. Now he had to live with the consequences of his words, or more precisely, die with them.

His troops spent the night listening to the American loudspeakers, hearing the shells being registered, knowing exactly what dawn would bring. Some slept from exhaustion. Some prayed. Some wrote final letters they knew would never be delivered. And some began to question whether their commander’s honor was worth their lives.

Dawn arrived with mathematical precision at 600 hours, and with it came the artillery, not the random harassment fire that soldiers learned to endure, not the scattered shelling that allowed hope of survival through luck and dispersion, but methodical coordinated destruction that treated the fortress as a problem. in engineering rather than a military target.

12 heavy guns opened fire simultaneously. Their crews working with the practiced efficiency of factory workers on an assembly line. Each gun had specific targets, specific wall sections that intelligence had identified as structurally vulnerable. The shells didn’t scatter randomly across the fortress, but concentrated on these predetermined points, hitting the same locations again and again with the patient persistence of a hammer driving a nail.

The sound was overwhelming, a continuous thunder that made thought impossible and communication pointless. Inside the fortress, German soldiers huddled in whatever cover they could find, hands pressed over ears, mouths open to equalize pressure, bodies curled against stone walls that transmitted each impact as a physical shock.

The major had positioned his troops in defensive positions overnight, manning the walls and observation posts, preparing to repel the ground assault he assumed would accompany the bombardment. Within 15 minutes, those positions became death traps as American gunners walked their fire along the walls with surgical precision.

The fortress had been built to withstand artillery, but not this kind of artillery, not this concentration of fire maintained hour after hour without pause. The French engineers who designed these walls had calculated for the cannons of their era for the relatively light shells that 19th century guns could deliver. They had not imagined 155 mm howitzers firing high explosive rounds that could crack stone and expose the rubble fill between the outer and inner wall faces.

The first breach opened at 6:45 hours on the eastern wall, a section that had taken 47 direct hits in 45 minutes. Stone blocks that had stood for a century suddenly lost their structural integrity, and a section of wall 5 m wide collapsed inward, creating a ramp of rubble that led directly into the fortress interior.

The German major attempted counterbatter fire, ordering his few artillery pieces to target the American gun positions. The response was immediate and devastating. American counterbar had tracked his guns the moment they fired, and within 90 seconds, concentrated fire was falling on those positions.

The German guns managed perhaps three rounds each before being silenced permanently. Their crews killed or scattered, the weapons themselves damaged beyond field repair. The lesson was clear and brutal. Shooting back meant instant death. The only survival strategy was to hide and endure. At 800 hours, the artillery shifted targets.

Instead of concentrating on wall sections, the guns began systematically destroying everything inside the fortress that rose above ground level. Observation posts disintegrated under direct hits. Defensive positions carved into the walls were collapsed by shells that struck with uncanny accuracy. The command post, a reinforced structure the major had established in what had been the fortress’s original headquarters building received special attention.

American intelligence had identified its location through aerial reconnaissance and now three batteries concentrated their fire on that single target. The P47 Thunderbolts arrived at 8:30 hours. Four aircraft in two pairs, their approach announced by the distinctive sound of their engines. They came in low, their pilots having studied reconnaissance photographs until they could navigate the fortress layout from memory.

The first pair carried 500B bombs, and their target was the major’s command post. The building had already been reduced to rubble by artillery, but the pilots put their bombs directly into the wreckage with the precision that made the Thunderbolt one of the war’s most effective ground attack aircraft. The first bomb penetrated what remained of the roof before detonating, and the blast wave that emerged from the structures, windows, and doors carried debris, and dust in a perfect sphere of destruction.

The second pair of thunderbolts targeted the ammunition storage areas that intelligence had identified in the fortress’s underground chambers. Their bombs were fused for delayed detonation, designed to penetrate before exploding. The first bomb struck near the main ammunition bunker’s entrance. And 3 seconds later, the underground detonation triggered a secondary explosion that dwarfed anything the Americans had delivered.

The fortress’s own ammunition stored in what the Germans had believed was a safe location erupted in a fireball that rose 30 m into the air. The blast wave knocked down sections of wall that the artillery had weakened and the subsequent fires sent smoke billowing across the entire position.

Throughout the bombardment, the American loudspeakers continued their broadcast, describing what was happening and what would come next. The voice was calm, almost conversational, speaking in fluent German with a slight. Austrian accent. Your commander’s headquarters has been destroyed. Your ammunition storage has been destroyed. The eastern wall has been breached.

In 30 minutes, the ground assault will begin. You may surrender at any time by emerging through the breaches with your hands raised and your weapons left behind. Your commander chose this. You do not have to die for his choice. The first surreners came at 8:45 hours. small groups of soldiers emerging from the smoke and dust with hands raised, stumbling over rubble toward American lines.

They were young men, mostly teenagers who had been in uniform for weeks rather than years, who had joined an army that was already defeated and found themselves trapped in a fortress commanded by a man who valued abstract honor over concrete survival. American military police processed them efficiently, searching for weapons, providing water, directing them to collection points behind the lines.

The soldiers looked dazed, shocked by the violence they had endured, grateful to be alive and out of the fortress. The major attempted to maintain order by having would be surrenderers shot as traders. He established blocking positions at the breaches, ordering his most loyal troops to fire on anyone attempting to leave.

The policy backfired spectacularly. German soldiers who might have continued fighting rather than risk crossing open ground under fire now faced the certainty of being shot by their own side if they stayed. The blocking positions themselves became targets as soldiers who wanted to surrender turned their weapons on the men preventing their escape.

Small firefights erupted within the fortress. German shooting German, the command structure collapsing into chaos as survival instinct overwhelmed military discipline. By 9:30 hours, the fortress had been reduced to wreckage. The walls were breached in four locations, creating multiple entry points that eliminated any possibility of concentrated defense.

The command post was destroyed. The ammunition storage was destroyed. The main gate had been blasted off its hinges by a direct hit from a 500B bomb. Fires burned in multiple locations, sending smoke across the position that reduced visibility to a few meters. The systematic bombardment had accomplished its purpose.

The fortress no longer functioned as a defensive position, but had become a collection of isolated strong points with no coordination and no coherent command. The ground assault began at 1,000 hours with simultaneous attacks through every breach. Sherman tanks rolled forward, their 75 mm guns firing at pointblank range into any structure that might contain defenders.

Infantry followed in squad-sized units, moving with the practiced efficiency of men who had conducted dozens of similar operations. Flamethrowers cleared bunkers. The weapons psychological impact often more effective than its physical destruction as German soldiers emerged rather than face burning.

Engineers used satchel charges on remaining strong points, blasting through walls and doors with explosives that made resistance pointless. The fighting was systematic and mechanical, lacking the chaos that typically characterized urban warfare. American units advanced on predetermined schedules, clearing assigned sectors with methodical thoroughess.

German resistance was sporadic and uncoordinated. Individual soldiers or small groups fighting from isolated positions without support or communication with other defenders. Some fought because they believed they had no choice. Some because they were too shocked to make rational decisions. some because the major’s blocking positions left them trapped between American attackers and German executioners.

The major was found at 10:45 hours, barricaded in what remained of his command bunker with perhaps a dozen loyal troops. The bunker had survived the bombardment through a combination of robust construction and luck, but it was now surrounded, isolated, and without any possibility of relief or escape. American engineers placed shaped charges against the bunker’s steel door, and the explosion that followed blew the door inward and filled the interior with smoke and dust.

When the smoke cleared, the major stood in the bunker’s entrance with a pistol in his hand, his uniform torn and covered in dust, his face showing the strain of the past 4 hours. An American sergeant, a veteran of campaigns in North Africa and Sicily, assessed the situation in the fraction of a second that combat experience provides.

The major’s pistol was rising, his intention clear. The sergeant’s M1 Garand was already at his shoulder, and he fired twice, both rounds striking center mass. The major collapsed, his pistol clattering on stone, his stated preference for death over surrender fulfilled exactly as he had requested. The German soldiers behind him immediately dropped their weapons and raised their hands.

Their loyalty to their commander apparently not extending to dying alongside him. The battle statistics revealed arithmetic that was brutal in its clarity. From the first artillery round at 600 hours to the final surrender at 1100 hours, less than 12 hours had elapsed from Patton’s order to the fortress’s capture. [snorts] American casualties were minimal.

Seven wounded, none seriously, zero killed. The overwhelming firepower and methodical approach had accomplished exactly what Patton intended, eliminating the position without exposing his troops to significant risk. German casualties told a different story. Approximately 200 killed, 300 wounded, and 1,000 surrendered. The major’s decision to fight had cost his command roughly onethird of its strength in dead and wounded, accomplishing nothing except adding names to casualty lists.

Post battle intelligence teams found evidence that made the tragedy even more pointed. Notes from junior officers questioning the decision to fight, suggesting that surrender would save lives without changing the strategic situation. Testimony from prisoners about soldiers executed for attempting to surrender.

About the majors insistence that honor required fighting to the death. The fortress had held for less than a day. Delaying Patton’s advance by perhaps 12 hours. Accepting surrender would have saved 1,500 lives and produced the same strategic outcome. Patton tooured the fortress that afternoon, walking through the rubble with the same matterof fact demeanor he had shown when ordering the attack.

He examined the breaches, noting how the concentrated artillery fire had accomplished its purpose. He inspected the destroyed command post, observing the effectiveness of the air strikes. When staff officers asked for his assessment, his response was characteristically direct. The major said we would have to kill him. We did.

He personally visited the aid station where wounded German prisoners were receiving medical treatment ensuring that American medics were providing the same care they would give their own wounded. This was Patton’s philosophy in action. Ruthless in combat, professional in victory. The enemy deserved destruction when fighting, respect when defeated.

The wounded prisoners looked at him with expressions mixing fear and confusion, unable to reconcile the legendary American general with the man who was ensuring they received proper medical attention. The story spread through German forces with remarkable speed, becoming a teaching moment more effective than any propaganda.

Radio intercepts picked up German commanders discussing the fortress’s fall, analyzing what had happened, drawing conclusions about what it meant to challenge Patton directly. The lesson was clear. Patton’s threats were not negotiations or bluffs, but statements of fact. When he said he would do something, he would do exactly that with overwhelming force and absolute efficiency.

Challenging him meant he would accept your challenge and fulfill. Your stated preference, whether that preference was surrender or death, the major’s defiance had accomplished nothing measurable. 200 men killed, 300 wounded. The position held less than a day. Patton’s advance delayed by hours rather than days or weeks.

Accepting surrender would have saved all 1,500 lives with the same strategic outcome. The fortress would have changed hands. The roads would have been secured and the war would have continued on its inevitable trajectory toward German defeat. The only difference was the casualty count and the story that emerged from the rubble.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.