Japanese Infantry Charged US “Anti-Air” Trucks—4 .50 Cals Erased the Banzai Wave

Four M2 Browning machine guns mounted on a single rotating platform can fire 2300 rounds per minute. When Japanese infantry charged American positions on the Villa Verde Trail in the spring of 1945, they discovered what that volume of fire could do to human bodies. The vehicles they faced weren’t designed to kill soldiers.

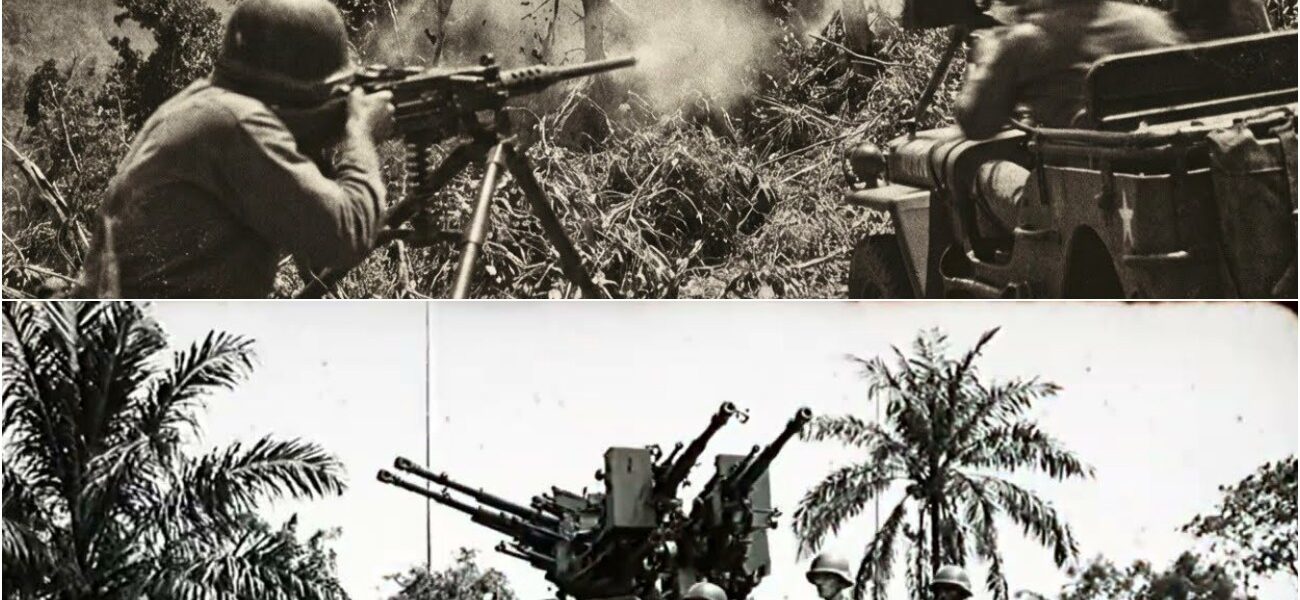

They were anti-aircraft platforms repurposed for ground combat. The Japanese called them death machines. American crews called them meat choppers. The M16 multiple gun motor carriage arrived in the Philippines with a reputation problem. Designed specifically to shoot down low-flying enemy aircraft. The vehicle combined an M3 halftrack chassis with an M45 quad mount.

Four 50 caliber M2 Browning machine guns arranged in a square pattern capable of rotating 360° and elevating up to 90°. 2700 units rolled off production lines between May 1943 and March 1944. Manufactured by White Motor Corporation for the express purpose of providing mobile air defense to advancing ground forces.

But the Pacific theater presented an unexpected challenge. Japanese air power, once formidable, had been systematically degraded by early 1945. American crews found themselves manning sophisticated anti-aircraft systems with virtually no aircraft to shoot at. The vehicle weighed 9.9 tons fully loaded and measured 21 feet 4 in in length.

Armor plating of 12 mm protected the crew compartment on the front and sides. Enough to stop small arms fire and shrapnel, but useless against direct hits from artillery or anti-tank weapons. The halftrack configuration combined front wheels for steering with rear tracks for traction, allowing the vehicle to traverse terrain that would immobilize purely wheeled vehicles while maintaining road speeds up to 42 mph on improved surfaces.

Five crew members operated each M16, a driver, a vehicle commander, and three gunners who rotated responsibilities manning the quad mount and feeding ammunition. Each M2 Browning machine gun in the quad mount fired 50 caliber ammunition, the 12.7 millimeter BMG round, at a cyclic rate between 450 and 575 rounds per minute.

The combined theoretical rate of fire for all four guns operating simultaneously reached 2300 rounds per minute. In practice, crews fired in controlled bursts to manage barrel temperatures and ammunition consumption. But even conservative firing patterns could send hundreds of rounds downrange in seconds. The muzzle velocity of 2900 ft per second gave each projectile tremendous kinetic energy.

The 50 caliber round had been designed to penetrate aircraft aluminum and damage engine blocks against unarmored human targets. The results were catastrophic. If you’re getting value from this deep dive into documented military history, hit that like button and subscribe. We bring you the technical analysis and real combat accounts that other channels skip.

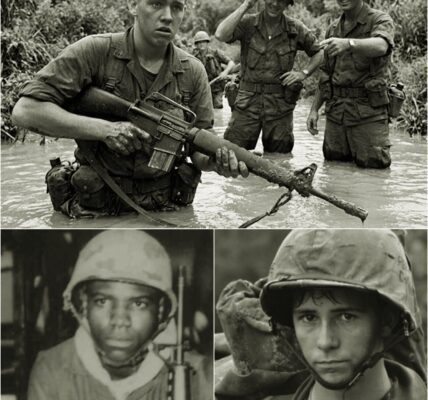

The tactical situation on Luzon in early 1945 forced American commanders to reconsider the role of anti-aircraft assets. The 32nd Infantry Division, known as the Red Arrow Division for its reputation of piercing every defensive line it encountered, had landed on Luzon in January 1945 after brutal fighting on Lee.

The division received only 3 weeks of rest before being committed to operations in northern Luzon. And by February, the unit was already under strength and exhausted. Their mission, advance through the Carabalo Mountains along the Vila Verde Trail, a 27mile mountain track that served as a critical approach to the Kagayian Valley. Japanese forces under the command of General Tommoyuki Yamashitta had transformed the mountains into a fortress.

Major General Haruo Konuma commanded the Bambang branch of the 14th area army, orchestrating a defensive strategy that maximized the terrain’s natural advantages. Engineers had carved defensive positions into the mountain sides, creating mutually supporting networks of caves, tunnels, and bunkers. Machine gun nests covered every approach.

Artillery pieces hidden in cave complexes could rain fire on American positions while remaining immune to counterbatter fire. Spider holes and sniper positions proliferated throughout the jungle. The high ground overlooking the trail became known as Yamashita Ridge, named for the Japanese commander whose defensive doctrine turned each ridge into a killing ground.

Yamashita understood he couldn’t defeat the Americans. His strategy focused on attrition, bleeding American units so severely that the cost of taking the Philippines would drain resources needed for the planned invasion of Japan. The Villa Verde Trail became the focal point of this strategy. The nearly perpendicular slopes, bald razorback ridges, and dense jungle forced American infantry into predictable avenues of approach.

Japanese defenders could observe movement from elevated positions and deliver devastating fire at their choosing. The 32nd Division began its assault on the Villa Verde Trail on February 21st, 1945.Progress measured in yards. Casualties mounted rapidly. The division’s 127th Infantry Regiment attacked on February 24th, attempting coordinated battalion level maneuvers despite terrain that channeled movement into narrow corridors.

American commanders quickly recognized that conventional infantry tactics were producing unacceptable casualty rates without corresponding gains. The Japanese defensive positions were simply too well constructed and too wellsighted to be reduced by rifle fire and grenades alone.

This is where the M16 multiple gun motor carriage entered the tactical equation. The 209th anti-aircraft artillery battalion had deployed to Luzon with standard air defense missions. But with Japanese aircraft largely absent from the skies, battalion commanders began receiving requests from infantry units for ground support. The initial response was skeptical.

Anti-aircraft crews trained to track fastmoving aircraft and calculate lead angles for aerial interception. They practiced elevation and traverse speeds appropriate for targets moving in three dimensions at hundreds of miles hour. The prospect of using these weapons against ground targets seemed like a waste of specialized capabilities.

But the mathematics of firepower told a different story. 2300 rounds per minute represented more sustained fire than any other mobile weapon system in the American arsenal. A single M16 could deliver more projectiles downrange than an entire infantry platoon armed with M1 Grand Rifles and Browning automatic rifles.

Each 50 caliber round carried exponentially more kinetic energy than the 306 ammunition used by infantry weapons. The penetrating power of the 50 caliber round could defeat the wooden logs and packed earth that provided overhead cover for Japanese positions. Trees that concealed sniper nests could be literally cut down by sustained fire.

Field commanders began requesting M16 support for specific missions. Take out a cave entrance, suppress a ridgeel line, provide covering fire for an infantry advance. The anti-aircraft crews discovered that their training translated surprisingly well to ground targets. The electric guidance system on the M45 quad mount designed for tracking aircraft allowed for smooth traverse and precise aiming against stationary positions.

The ammunition loading procedures remained identical regardless of target. The primary adjustment required was psychological, accepting that their carefully maintained anti-aircraft platform was about to become a direct fire weapon. The first combat employment of M16s in ground support roles on the Villa Verde Trail occurred in late February 1945.

A company of the 209th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion attached vehicles to the 32nd Infantry Division, deploying them along portions of the trail where terrain permitted vehicle movement. Engineers had been working continuously to widen the trail and reinforce surfaces to support heavier vehicles, using demolition charges to blast away rock faces and create routes barely wide enough for halftrack passage.

Initial engagements validated the concept immediately. When M16 crews engaged Japanese positions with sustained fire, the volume of outgoing rounds overwhelmed defensive positions designed to withstand rifle fire and light machine guns. The 50 caliber projectiles punched through log reinforced bunker walls.

They penetrated cave entrances and ricocheted through tunnel systems. Trees and vegetation that provided concealment were shredded, exposing previously hidden positions. Japanese soldiers caught in the open had no defense against the intersecting cone of fire produced by four machine guns operating simultaneously. But the weapon’s true test came when Japanese forces launched counterattacks using bonsai charge tactics.

The term bonsai charge derives from the battlecry Japanese soldiers used when conducting human wave attacks, mass infantry assaults relying on shock, speed, and the willingness to accept catastrophic casualties to achieve breakthrough. The tactic had shown effectiveness in China, particularly against forces lacking automatic weapons or adequate entrenchments against opponents with machine guns and prepared positions.

The results were typically disastrous for the attackers, but Japanese military doctrine emphasized the psychological impact of the charge and viewed mass casualties as an acceptable cost. Understanding what happened when Japanese infantry charged M16 positions requires examining the specific capabilities of the M2 Browning machine gun and the tactical reality of human wave attacks.

The M2 Browning, developed by John Browning and entering service in the 1920s, operates on a short recoil principle where the barrel and bolt recoiled together for a short distance before the bolt continues rearward to extract and eject the spent cartridge. A fresh round is stripped from the ammunition belt and chambered as the bolt returns forward.

This cycle repeatsbetween 450 and 575 times per minute per gun. The ammunition belt feeding system allows sustained fire limited only by barrel temperature and ammunition supply. Each M16 carried substantial reserves of linked 50 caliber ammunition, typically several thousand rounds distributed in ammunition boxes throughout the vehicle. Crews could maintain high rates of fire for extended periods, pausing only to change belts and allow brief cooling intervals.

The air cooled design relied on atmospheric cooling of the barrel, which functioned adequately at the sustained rates typical of ground combat. The projectile itself, the 50 caliber Browning machine gun round, measures 12.7 mm in diameter and 99 mm in total length. The standard M33 ball round features a full metal jacket bullet weighing approximately 43 g propelled to a muzzle velocity of 2,900 ft per second.

This combination of mass and velocity delivers approximately 18,000 jewels of kinetic energy at the muzzle. For comparison, the 306 round used in the M1 Garand rifle delivers approximately 3600 jewels. The 50 caliber round carries five times the energy. That energy manifests in extreme terminal effects on soft targets. The 50 caliber round was never intended for use against unarmored personnel.

Its design specifications focused on penetrating aircraft structures and disabling mechanical systems. When such a projectile strikes a human body, the results exceed the bounds of what military medical personnel consider survivable wounds. The projectile diameter alone is sufficient to disrupt major organs and sever limbs.

The hydrostatic shock wave created by the projectiles passage through tissue causes massive temporary cavitation, destroying tissue far beyond the permanent wound channel. Center mass hits are immediately fatal. Peripheral hits to extremities result in traumatic amputation. Now multiply that effect by four guns firing simultaneously.

The M45 quad mount arranged the four M2 Browning guns in a square pattern, two on each side of the gunner’s position. The spacing between guns created an intersecting fire pattern where projectiles from all four weapons converged on the target area. When crews adjusted their aim to sweep across a target zone, they created what contemporary accounts described as a wall of fire, a continuous stream of 50 caliber projectiles covering a horizontal area.

Japanese forces launching bonsai charges typically formed up in assembly areas and advanced in waves, soldiers running at full speed while screaming battle cries. The tactic relied on closing the distance to American positions before defensive fire could inflict sufficient casualties to halt the momentum.

Against riflear armed infantry, this sometimes worked. The rate of fire from boltaction rifles might not generate sufficient casualties fast enough to stop determined attackers willing to die. Against automatic weapons like the Browning automatic rifle or light machine guns, the tactic became increasingly costly as the war progressed, but small unit tactics could sometimes find gaps in defensive fire.

Against an M16, there was no gap. The combined rate of fire meant that in the time it took a soldier to run 50 m, approximately 10 seconds at sprint speed, the quad mount could fire nearly 400 rounds. Those rounds didn’t arrive in a stream at a single point. The gunner traversed the mount, sweeping the fire across the approaching formation.

Every soldier in the charge entered the beaten zone simultaneously. Documented engagements between M16 vehicles and Japanese infantry occurred throughout the Villa Verde Trail campaign between late February and May 1945. One particular incident on May 8th, 1945 was photographed and later verified by unit records from a company, 209th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion attached to the 32nd Infantry Division.

The M16 was positioned on a firing point along the trail, engaging Japanese positions identified in the Cababayro Mountains. The photograph shows the quad mount elevated at approximately 45°, indicating the target was on higher ground relative to the vehicle’s position. The tactical situation that led to this engagement typified the challenges faced throughout the campaign.

Japanese forces had established defensive positions in a cave complex on the ridge above the trail. American infantry attempting to advance came under fire from multiple positions. Machine guns covered the trail itself, while riflemen in spider holes engaged from closer range. Artillery fire from concealed positions on the reverse slope of the ridge prevented American forces from massing for a coordinated assault.

The terrain prevented flanking maneuvers. Direct assault would produce catastrophic casualties. Engineers had managed to create a vehicle accessible route to a position offering direct line of sight to some of the cave entrances. An M16 from the 209th was directed forward. The halftrack advanced along the narrow trail tracks gripping the loose rock andsoil while the driver maintained control on the steep grade.

The vehicle commander had identified the cave complex from earlier reconnaissance and directed the crew to a firing position offering the best angle of engagement. The gunner elevated the quad mount to match the angle to the target approximately 150 m distant and 50 m above the vehicle’s elevation. The electric traverse system allowed precise aiming despite the vehicle being positioned on uneven ground.

Once the mount was oriented, the gunner opened fire. All four guns fired simultaneously, sending 2300 rounds per minute toward the cave entrances. The effect was immediate and overwhelming. 50 caliber projectiles impacted the rock face around the cave entrances, creating a continuous cascade of stone fragments and ricochets.

rounds entering the cave mouths bounced through the interior spaces, making the caves death traps for anyone inside. The sustained fire, lasting approximately 90 seconds, according to crew accounts, delivered nearly 3,500 rounds on target. The volume of fire suppressed every defensive position in the target area.

Japanese soldiers who attempted to return fire or reposition were cut down. Those who remained in the caves were killed by ricochets or buried by rock collapses caused by the sustained pounding. Infantry elements advancing behind the M16’s suppressive fire were able to close with the positions and use flamethrowers and demolition charges to seal the caves permanently.

What had been an insurmountable obstacle was reduced in less than 2 minutes of sustained fire from a single vehicle. But that engagement, devastating as it was, involved stationary targets. The encounters between M16 crews and bonsai charges, presented different tactical dynamics. These occurred primarily during nighttime or early morning hours when Japanese forces attempted to infiltrate American lines or conduct local counterattacks to reclaim lost positions.

One documented series of engagements occurred in late March 1945 on approaches to Hill 604 along the Villa Verde Trail. The 128th Infantry Regiment, part of the 32nd Division, had seized forward positions on the lower slopes of the hill. Japanese forces estimated at company strength, assembled for a counterattack designed to retake the lost ground.

American defensive positions included infantry units in foxholes and prepared positions supported by machine gun teams and mortar crews. An M16 had been positioned in a slight depression approximately 50 m behind the forward line. Initially intended to provide anti-aircraft coverage, but reconfigured for ground support.

The Japanese attack began in the pre-dawn darkness with infiltrators attempting to approach American positions silently before launching the final charge. American sentries detected movement and fired illumination rounds. The flares revealed hundreds of Japanese soldiers advancing across open ground toward the American positions, moving at a run with bayonets fixed and officers leading with swords drawn.

The M16 crew, alerted by the illumination rounds, traversed their mount toward the approaching force. The gunner acquired the target mass, not individual soldiers, but the formation as a whole and opened fire. The quad mount traverse system allowed the gunner to sweep the fire horizontally across the formation. The effect, according to survivors who witnessed the engagement, was apocalyptic.

The first burst caught the lead elements of the charge. Soldiers in the front rank were literally torn apart by multiple simultaneous hits. Those immediately behind them were struck by the same burst as the gunner continued traversing. The momentum of the charge carried soldiers forward even as casualties mounted catastrophically. Men fell in groups.

The intersection of fire from four guns meant that each soldier entering the beaten zone was struck by multiple projectiles simultaneously. Bodies were flung backward by the kinetic impact, limbs separated from torsos. The visual effect in the flickering illumination was of human forms disintegrating. The gunner traversed back across the formation, firing a second sustained burst, then a third.

The rate of fire was such that in the time span of perhaps 15 seconds, more than 500 rounds had been delivered into a target area of approximately 100 m width and 50 m depth. Every soldier in that zone was hit. Many were hit multiple times. The charge simply ceased to exist as a coherent formation. Those who survived the initial bursts, soldiers on the flanks or rear of the formation, broke and retreated into the jungle.

American infantry defending the position reported that they had fired few shots. The M16 had broken the attack before it reached effective rifle range. The ground in front of the defensive position was carpeted with casualties. When dawn allowed assessment, casualty counts exceeded 100 Japanese soldiers killed in less than 60 seconds of engagement.

The M16 crew had expendedapproximately 800 rounds of 50 caliber ammunition. Japanese commanders observing these engagements quickly recognized the threat posed by M16 vehicles. Intelligence reports identified the distinctive silhouette of the quad mount and attempted to develop countermeasures. The challenge was that the M16 combined overwhelming firepower with mechanical mobility, making it difficult to target with the infantry weapons available to Japanese forces.

The 12mm armor plating on the vehicle was sufficient to defeat rifle fire and light machine gun rounds at combat ranges. Heavier weapons capable of disabling the vehicle, anti-tank rifles or artillery required time to aim and fire, and the M16’s rate of fire made that time unavailable. Some Japanese units attempted to specifically target M16 vehicles with infiltration teams carrying magnetic mines or satchel charges.

The tactic required soldiers to approach the vehicle closely enough to place explosives directly on the hull. a near suicidal mission given the vehicle’s defensive armament. Several documented attempts occurred throughout the Villa Verde Trail campaign with Japanese soldiers attempting to approach M16 positions during darkness or using terrain for concealment.

One such attempt occurred during a night engagement when Japanese infiltrators managed to reach within 30 m of an M16 position. The vehicle was parked in a defensive position with the crew maintaining watch but not actively engaged. Japanese soldiers approached through a gully that provided defilade from direct observation.

The attack was detected when the lead infiltrator triggered a trip wire connected to illumination flares American crews had imp placed around the perimeter. The sudden illumination revealed multiple Japanese soldiers advancing with explosive charges. The M16 crew reacted within seconds. The gunner traversed the mount downward to minimum elevation and fired a burst directly into the approaching group.

At that range, less than 30 m, the effect was instant annihilation. The 50 caliber rounds struck with full kinetic energy, unddeinished by flight time or air resistance. Bodies were destroyed rather than merely killed. The engagement lasted approximately 3 seconds and expended fewer than 100 rounds. No infiltrator survived to reach the vehicle.

Japanese forces also attempted to engage M16 vehicles with artillery fire when the vehicles were stationary or moving along predictable routes. This proved more effective when Japanese observers could direct fire accurately. The M16’s armor protection was irrelevant against direct hits from artillery shells. Several vehicles were disabled or destroyed during the Villa Verde Trail campaign when caught by artillery fire, but the mobility of the halftrack chassis and the training American crews received in tactical movement limited the effectiveness of

this approach. M16s learned to displace rapidly after engaging targets, moving to alternate positions before Japanese artillery could respond. The psychological impact of M16 firepower on Japanese forces became a factor in tactical planning. Prisoners captured during later stages of the Villa Verde Trail campaign reported that soldiers dreaded encounters with the fire trucks.

Their term for the M16 based on its appearance and devastating effect. Some units showed reluctance to conduct bonsai charges when intelligence suggested M16 vehicles were present in the defensive area. This represented a significant shift in Japanese tactical behavior as the willingness to conduct suicidal attacks had been a consistent feature of Japanese defensive doctrine throughout the Pacific War.

But desperation often overruled tactical caution. As the Villa Verde trail campaign progressed into April and May 1945, Japanese defensive positions became increasingly isolated and undersupplied. Units cut off from resupply had limited ammunition and dwindling food stocks. The decision calculus for local commanders shifted.

Conducting a banzai charge against hopeless odds became preferable to slow starvation or surrender, which Japanese military culture considered unacceptable. These late campaign charges often involved smaller units, platoon or squad-sized elements rather than company strength formations, but the tactical result remained consistent.

When these charges encountered M16 defensive positions, the outcome was predetermined. The mathematics of firepower ensured that no infantry force, regardless of courage or determination, could survive in the beaten zone of a quad 50 caliber mount, firing at full rate. Operating an M16 in ground combat roles presented challenges that anti-aircraft crews had not trained for.

The most immediate was ammunition consumption. In the air defense role, engagements were typically brief. Aircraft passed through the firing zone in seconds, requiring short bursts at high volume. Ground support missions, particularly when suppressing defensive positions or engaging infantryformations, required sustained fire over longer periods.

This dramatically increased ammunition expenditure. Each M2 Browning gun fired from ammunition belts containing linked rounds. The standard configuration allowed for belts of various lengths with longer belts preferred for sustained fire to reduce the frequency of reloading. But even with optimal belt configuration, sustained fire at cyclic rate exhausted ammunition supplies rapidly.

Crew members not actively operating the mount spent much of their time during engagements feeding ammunition belts and preparing replacement belts for immediate use. The logistics of ammunition supply became a critical factor. Each M16 could carry several thousand rounds of 50 caliber ammunition in its onboard storage, but intensive combat operations could deplete that supply in a single day.

Resupply convoys had to prioritize 50 caliber ammunition for M16 units operating in ground support roles, sometimes at the expense of other munitions. Battalion supply officers struggled to predict consumption rates based on mission profiles. The difference between a quiet day with no contact and an active day with multiple engagements could be thousands of rounds per vehicle.

Barrel wear and overheating presented additional challenges. The M2 Browning was designed as an air cooled weapon, relying on atmospheric heat dissipation to manage barrel temperatures during firing. In the anti-aircraft role, brief engagement times allowed barrels to cool between targets. Ground support missions involving sustained fire pushed the guns beyond their design parameters.

Crews learned to fire in controlled bursts with brief pauses to manage heat buildup, but prolonged engagements could still result in barrels reaching temperatures that affected accuracy or in extreme cases caused rounds to cook off. firing spontaneously due to residual barrel heat. Crew training required adaptation.

Anti-aircraft gunners had learned to track moving aerial targets, calculating lead angles and elevation adjustments for aircraft velocities. Ground targets presented different challenges. Judging range to stationary positions, adjusting for slope and elevation differences, understanding the effects of sustained fire on different target types.

Much of this learning occurred on the job with crews developing practical expertise through repeated engagements. The psychological experience of operating the weapon in ground support mode differed significantly from air defense missions. Engaging aircraft was abstract. Targets were fast-moving shapes at distance and the results of fire were often uncertain.

Engaging ground targets, particularly masked infantry formations, provided immediate and graphic feedback. Gunners could see the effects of their fire in explicit detail. The human cost was visible and undeniable. Some crew members found this psychologically difficult. They had volunteered for anti-aircraft duty with the understanding that they would be shooting at machines, not people.

The transition to ground support forced them to confront the human reality of their weapons effects. Unit records and personal accounts from the period indicate that crew members processed this in different ways. Some focused on the tactical necessity. Their fire was protecting American infantry from Japanese attacks.

Others struggled with the visual memory of what the quad mount did to human bodies. But there was widespread recognition among infantry units that the M16 had become an invaluable asset. Infantry commanders requested M16 support for difficult missions. Knowing that the fire support provided could make the difference between success and catastrophic casualties.

Bonds developed between infantry units and the M16 crews supporting them. Mutual respect grew from shared combat experiences. The infantry protected the more lightly armored vehicles from close-range threats while the M16 crews provided the overwhelming firepower that broke defensive positions and shattered counterattacks.

The Villa Verde trail campaign concluded on May 31st Secret 1945 with American forces securing the trail and breaking Japanese defensive positions in the Carabalo Mountains. The 32nd Infantry Division despite its exhaustion and casualties had achieved its mission of opening the route to the Kagan Valley and eliminating organized Japanese resistance in the region.

The cost had been severe. Casualty rates for the division during the campaign were among the highest sustained by any American unit in the Philippines. The tactical employment of M16 vehicles in ground support roles contributed to the eventual success, though quantifying that contribution precisely is difficult.

What can be stated definitively is that M16 crews engaged in numerous documented actions throughout the campaign, providing fire support that infantry commanders considered essential. The vehicle’s ability to deliver overwhelming firepower against hardened defensivepositions and to break infantry charges with minimal friendly casualties represented a significant tactical advantage.

General Tommoyuki Yamashita continued to direct Japanese resistance in northern Luzon through the end of the war. But the fall of the Villa Verde trail positions marked the collapse of organized defensive strategy. Japanese forces reverted to isolated resistance from remaining mountain strongholds, conducting only local actions rather than coordinated defense.

Yamashita surrendered on September set 1945. Following Japan’s acceptance of unconditional surrender terms, the M16 multiple gun motor carriage saw limited deployment in the Pacific theater overall with the Va Verde Trail campaign representing its most significant ground combat employment. Most M16 production went to the European theater where the vehicle saw extensive use in ground support roles during the campaign through France and Germany.

The nickname meat chopper became widely used in both theaters, acknowledging the weapon’s devastating effect against personnel targets. The vehicle continued in service after World War II, seeing action in the Korean War, where M16 units again found themselves primarily employed in ground support roles rather than air defense.

The basic concept, multiple heavy machine guns on a mobile platform, proved so effective that it influenced subsequent armored fighting vehicle designs. Modern equivalents include vehicles mounting multiple automatic weapons for base defense and convoy protection. Continuing the legacy of overwhelming mobile firepower that the M16 pioneered, the employment of anti-aircraft weapons in ground support roles during World War II reflected broader patterns of tactical adaptation and weapons repurposing.

Military units facing unexpected combat situations consistently demonstrated ability to employ available weapons in ways designers never intended. The M16 represents perhaps the most dramatic example of this adaptive process. A weapon designed specifically for air defense, proving more valuable in a ground combat role.

The technical specifications that made the M16 effective against aircraft translated directly to effectiveness against ground targets. High rate of fire meant volume of fire. Large caliber ammunition meant destructive effect per hit. Electrical traverse and elevation systems meant precise target engagement. Armor protection meant survivability in forward positions.

Mobility meant rapid response to changing tactical situations. These attributes combined to create a weapon system that dominated tactical engagements despite being employed outside its design parameters. The lessons learned from M16 employment influenced post-war weapons development. The value of high volume sustained fire against personnel targets was recognized and incorporated into infantry weapons design.

The concept of mobile fire support platforms influenced armored vehicle development. The specific tactical techniques developed by M16 crews, positioning for optimal fields of fire, coordination with infantry maneuver elements, ammunition management during sustained engagements, became part of institutional knowledge that informed subsequent tactical doctrine.

The human dimension of these engagements deserves acknowledgement. Japanese soldiers conducting banzai charges demonstrated extraordinary personal courage even in the face of certain death. The tactic itself, however, represented a failure of military doctrine. Committing soldiers to attacks with no reasonable probability of success constituted wasteful expenditure of lives for minimal tactical gain.

That Japanese commanders continued to order such charges even after their futility became apparent speaks to cultural and institutional factors that valued symbolic resistance over rational tactical assessment. American crews operating M16 vehicles experienced combat stress related to the graphic nature of their weapons effects.

While all combat involves psychological trauma, the visual immediiacy of quadmount fire against masked personnel created particularly vivid memories. Postwar accounts from M16 crews indicate that many carried those memories for decades, struggling with the human cost even while understanding the tactical necessity.

The effectiveness of the M16 against banzai charges also highlights the broader transformation of infantry combat during World War II. Automatic weapons and high volume fire had made traditional mass infantry tactics obsolete. Charging formations could no longer close with defensive positions before being destroyed by defensive fire.

The era of human wave attacks as viable military tactics had ended. Though some military forces would continue to employ them for years afterward, always with catastrophic results. The M16 multiple gun motor carriage achieved fame as the meat chopper through documented combat performance that matched its grim nickname.

When Japanese infantry chargedAmerican defensive positions equipped with quad 50 caliber mounts, the outcome was never in doubt. The mathematics of firepower, 2300 rounds per minute of largec caliber ammunition created a beaten zone that no unarmored personnel could survive. The Villa Verde trail campaign demonstrated this reality repeatedly. Documented engagements show M16 vehicles breaking company strength banzai charges in under 60 seconds, delivering concentrated fire that caused catastrophic casualties and shattered attack momentum.

Cave complexes and fortified positions that resisted infantry assault were reduced by sustained fire from quad mounts. The vehicle designed to shoot down aircraft became one of the most feared ground combat weapons in the Pacific theater. The technical specifications tell part of the story. Rate of fire, caliber, muzzle velocity, kinetic energy, but the human reality transcended statistics.

Japanese soldiers who faced M16 fire described it as inescapable. a wall of projectiles that destroyed everything in its path. American infantry who fought alongside M16 units credited the vehicles with saving countless lives by providing fire support that broke enemy attacks and reduced defensive positions.

The 32nd Infantry Division’s eventual success in securing the Villa Verde Trail resulted from multiple factors. Infantry courage, artillery support, air strikes, engineering efforts, and tactical leadership all contributed. But the M16 vehicles of the 209th Anti-aircraft Artillery Battalion provided a critical capability that shaped tactical outcomes throughout the campaign.

When the situation required overwhelming firepower delivered rapidly at close range, the Quad 50 caliber mount provided that capability like no other weapon system available. The repurposing of anti-aircraft weapons for ground combat reflected the pragmatic adaptation that characterized American military operations during World War II.

Faced with tactical challenges, heavily fortified Japanese defensive positions, and suicidal infantry charges, commanders employed available resources regardless of original design intent. The M16 proved ideally suited to these missions despite being built for entirely different purposes. Historical assessment of specific weapon systems must acknowledge both their tactical effectiveness and their human cost.

The M16 was extraordinarily effective at killing enemy soldiers. That effectiveness saved American lives by breaking attacks and reducing positions that would otherwise have required costly infantry assaults. But the weapon’s devastating effect on human bodies created psychological burdens for the crews who operated it and moral questions about the nature of modern warfare that persist decades later.

What remains undeniable is the documented historical record when Japanese infantry charged American positions defended by M16 multiple gun motor carriages during the Villa Verde Trail campaign in 1945. The Quad 50 caliber mounts erased those charges with overwhelming firepower. The four M2 Browning machine guns mounted on a halftrack chassis delivered combined fire that no infantry formation could withstand.

The vehicle designed to shoot down aircraft became known as the meat chopper for the simple reason that the name accurately described what it did to enemy soldiers caught in its beaten zone. The technical capabilities 2300 rounds per minute, 50 caliber ammunition, mobile platform, electrical traverse, combined with tactical employment by trained crews to create a weapon system that dominated close-range engagements.

Japanese forces that had previously relied on banzai charges to break through American defensive positions found that tactic transformed into mass suicide when quad mounts were present. The psychological advantage that surprise and ferocity once provided disappeared when faced with firepower that could destroy entire formations before they closed to effective range.

The Villa Verde trail campaign of February through May 1945 represented some of the most difficult fighting in the Pacific theater. Japanese forces defending terrain they had fortified for months extracted a heavy toll from American attackers. But the systematic application of combined arms tactics, including the employment of repurposed anti-aircraft vehicles in ground support roles eventually broke the defensive positions and opened the route to the Kagayan Valley.

The M16 crews who supported that effort earned their place in the historical record through documented combat actions that demonstrated the devastating effectiveness of mobile quad 50 caliber firepower against personnel targets. 70 years after the Villa Verde Trail campaign, the basic principles demonstrated by M16 employment remain relevant. Volume of fire matters.

Caliber matters. Mobility matters. The ability to deliver overwhelming firepower at decisive moments shapes tactical outcomes. Modern weapon systems employ different technologies.electronic fire control, higher rates of fire, more sophisticated ammunition. But the fundamental concept of mobile fire support platforms traces lineage back through vehicles like the M16.

The Japanese soldiers who charged into M16 fire on the slopes of the Carabalo Mountains demonstrated courage that deserves recognition. Even as we acknowledge the futility of the tactic they employed, the American crews who operated the quad mounts carried out their assigned missions under difficult conditions, providing fire support that protected their fellow soldiers and contributed to eventual victory.

The vehicle that brought them together, the M16 multiple gun motor carriage, stands as an example of weapons adaptation, tactical innovation, and the reality that combat forces will always find ways to employ available tools for the missions they face, regardless of original design intent. The historical record documents what happened when anti-aircraft trucks equipped with four 50 caliber machine guns encountered Japanese infantry charges on the Villa Verie Trail in 1945.

The quad mounts fired. The charges were erased. The meat chopper earned its name through performance that matched the grim moniker. And the M16 multiple gun motor carriage secured its place in military history as one of the most effective ground support weapons of the Pacific War.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.