He Entered Occupied Poland to Track Trains, But an American Spy Discovered Auschwitz Instead. NU

He Entered Occupied Poland to Track Trains, But an American Spy Discovered Auschwitz Instead

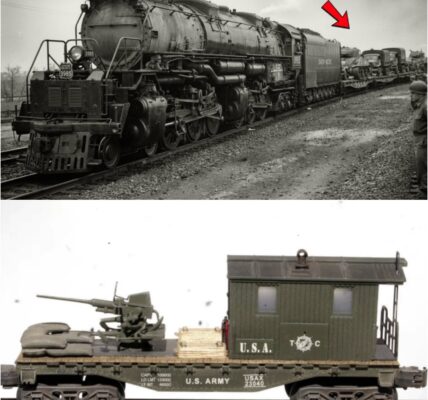

In October 1944, an American intelligence officer crossed into occupied Poland under a false identity. On paper, his task was straightforward: observe railway movements, document freight schedules, and determine how German transport networks were functioning as the war turned decisively against them.

He was not sent to investigate camps.

He was not ordered to collect testimony.

He was not prepared for what he would encounter.

Yet within weeks, his mission would shift from logistics to conscience—because the rails he followed did not simply carry supplies. They carried people. And they led to a place whose name would come to define an entire chapter of human history.

Disguised as an Ordinary Worker

The American operative worked under the umbrella of the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime organization tasked with gathering intelligence behind enemy lines. His cover was intentionally unremarkable: a French railway laborer displaced by the war, hired temporarily to assist with track maintenance and cargo handling.

Ordinary appearance was protection.

Invisibility was survival.

Dressed in worn clothes and carrying forged papers, he moved among civilians and workers who had learned not to ask questions. His job was to observe silently—count trains, note directions, record timing, and disappear into crowds.

But silence, in that part of Poland, carried its own dangers.

The First Whispers of Something Worse

It began not with sight, but with rumor.

Polish railway workers spoke in fragments—never full sentences, never openly. They used gestures, pauses, and glances over shoulders. Certain destinations were mentioned only indirectly. Certain trains were discussed as if they carried something unspeakable.

One name surfaced again and again.

Auschwitz.

The American had heard the name before in briefings, but only vaguely. It was described as a labor camp, one among many. Harsh, yes. Dangerous, yes. But nothing that matched the tone of fear now surrounding it.

The workers’ expressions told a different story.

Help from the Polish Resistance

Through careful contact, the American was introduced—quietly—to members of the Polish underground. These men and women had spent years collecting information under constant threat. They did not trust easily, but they understood the importance of reaching the outside world.

They told him what they knew.

They spoke of mass arrivals.

They spoke of separation.

They spoke of people who entered and never returned.

They did not use dramatic language. They did not need to.

What shocked the American most was not the content alone, but the certainty with which it was delivered. These were not rumors fueled by fear. These were observations repeated too often to ignore.

Following the Trains

The operative began focusing his work on a particular stretch of rail.

The trains came regularly.

They arrived full.

They left empty.

Sometimes smoke hung in the air. Sometimes a smell lingered—one that railway workers recognized instinctively and never named aloud.

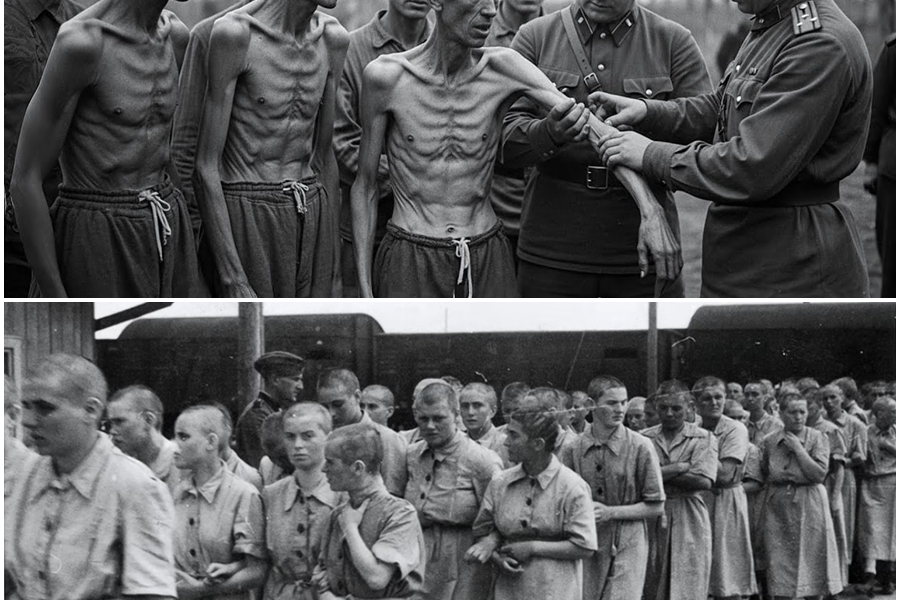

From a distance, he saw fences, guard towers, and movement that followed strict patterns. The scale was unlike anything he had encountered elsewhere.

This was not a temporary site.

This was an industrial operation.

Seeing Without Being Seen

The American never entered the camp. That would have meant immediate arrest and likely death. Instead, he observed from vantage points available to someone whose job required proximity but not access.

What he saw confirmed what he had been told.

Endless arrivals.

Rigid procedures.

A system designed for efficiency rather than care.

He recorded details obsessively: train numbers, timing, frequency, and the direction from which people arrived. He noted the age groups visible from afar. He noted how few left.

Each observation weighed heavier than the last.

The Moral Weight of Observation

Intelligence training emphasizes objectivity. Agents are taught to record facts, not emotions. But some facts resist detachment.

The American began to struggle.

He had entered enemy territory to gather information that would help win a war. Now he was witnessing evidence of a crime that transcended military objectives.

What good was counting trains, he asked himself, if no one understood what the trains were carrying?

Messages Hidden in Plain Sight

The Polish resistance had developed ingenious methods for moving information. Paper was dangerous. Radios were easily tracked. Words could be lethal.

So reports were hidden in bread loaves, sewn into clothing, memorized and passed orally across checkpoints. The American added his observations to these channels.

Dates.

Locations.

Patterns.

He stripped his reports of emotion, knowing that exaggeration could doom credibility. He focused on verifiable detail—the kind intelligence officers could not dismiss easily.

Even so, he feared the truth would be too large to absorb.

Crossing Enemy Lines with Evidence

Getting the information out was as dangerous as collecting it.

Couriers moved under constant threat. Entire networks could collapse if one person was caught. Each transfer was a calculated risk.

The American watched as his reports disappeared into the resistance system, carried by people who had already lost more than most could imagine.

He wondered if anyone on the other end would truly understand what these details meant.

Haunted by What He Could Not Stop

The operative remained in the region for weeks. Each day added another layer to what he could not unsee.

He continued his original assignment, but Auschwitz remained central in his thoughts. The war suddenly felt insufficient as a framework for understanding what was happening.

This was not simply occupation.

This was not merely repression.

It was something else entirely—something designed, deliberate, and systematic.

Returning With the Burden of Knowledge

When the American finally made his way back across enemy lines, he carried no photographs, no physical artifacts. He carried something far heavier.

Knowledge.

He delivered his reports to intelligence handlers who listened carefully, asked precise questions, and took notes. But he could sense hesitation—not disbelief, but disbelief’s cousin: incomprehension.

The scale was difficult to grasp.

The implications were unsettling.

The urgency was unclear.

The war still had to be won, they said. Priorities were fixed.

One of the First Americans to Know

History would later show that information about the camps reached Allied governments in fragments—often dismissed, delayed, or deprioritized.

The American understood, painfully, that knowing and acting were not the same thing.

He had done his duty as an intelligence officer.

He had also done something else: borne witness.

That dual role stayed with him long after the war ended.

The Aftermath of Bearing Witness

After the liberation of the camps, the truth became undeniable. Photographs, testimonies, and physical evidence flooded the world.

For the American, this confirmation brought no relief.

He had known earlier.

He had reported earlier.

And he had lived with the knowledge that, at the time, it was not enough.

He rarely spoke publicly about what he had seen. When he did, he focused not on himself, but on the systems that made such crimes possible—and on the cost of delayed understanding.

Why This Story Was Nearly Lost

Stories like his did not fit easily into postwar narratives.

They were too early.

Too uncomfortable.

Too revealing about how slowly truth moves through institutions.

So they survived in archives, footnotes, and private recollections rather than headlines.

Why It Still Matters

This story matters because it highlights a painful reality: awareness does not always lead to immediate action, even when the evidence is overwhelming.

It reminds us that witnessing is a responsibility—but also a burden.

And it shows how one individual, operating under orders that never mentioned morality, found himself forced to confront it anyway.

The Contrast That Defines the Story

The American spy entered Poland to track trains.

He left having tracked something far more devastating: the movement of human lives into a system built to erase them.

Between mission orders and moral truth, he chose not silence—but documentation.

And because of that choice, history gained one more thread of proof that, even in the darkest systems, someone was watching—and trying to tell the world what they saw.

Sometimes, the most powerful acts of resistance are not loud or immediate.

Sometimes, they are written quietly, hidden carefully, and carried across enemy lines by people who know that truth, once seen, can never be unseen.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.