Camps and Found Clean Beds, Medical Care, Prosthetic Workshops, and Unexpected RespectSupposed to Rule. NU

Camps and Found Clean Beds, Medical Care, Prosthetic Workshops, and Unexpected RespectSupposed to Rule

When disabled German soldiers were captured on the Western Front, most believed their fate was already sealed. Years of wartime messaging had prepared them for humiliation, neglect, or outright cruelty at the hands of their enemies. Injury, in particular, was seen as a liability—proof of weakness that would invite punishment rather than care.

Many arrived at American prisoner-of-war camps bracing themselves mentally for hardship. They had learned to expect stripped dignity, poor living conditions, and indifference toward their physical limitations. Some feared that their injuries would make them targets of mockery or neglect. Others believed they would simply be left to deteriorate quietly, forgotten and unwanted.

What they encountered instead left them stunned.

A First Shock: Clean Barracks and Order

The initial surprise came almost immediately. Instead of chaos or hostility, the camps were orderly. Barracks were clean. Beds were real beds, not bare ground. There were schedules, rules, and structure—but not brutality.

For disabled prisoners, this was disorienting. Many had spent months or years in environments where injury meant isolation or expendability. Now, they were being registered, housed, and accounted for with methodical care.

This was not kindness disguised as weakness. It was organization backed by intention.

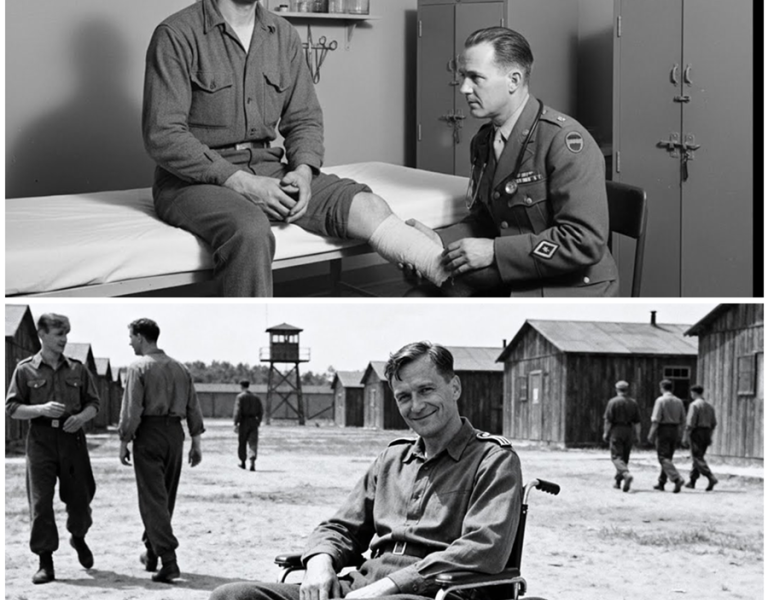

Medical Attention Without Conditions

Perhaps the most shocking discovery was medical care.

American camp doctors examined injuries carefully. Wounds were cleaned properly. Infections were treated. Pain was acknowledged instead of dismissed. Disabled prisoners were not rushed through examinations or treated as burdens.

For men who had been conditioned to believe that only the strong deserved attention, this approach felt unreal.

No one demanded loyalty.

No one asked for gratitude.

No one implied that care had to be earned.

Medical treatment was provided because it was considered necessary—and because the men were human.

Prosthetic Workshops Inside the Camps

The disbelief deepened when some prisoners were introduced to prosthetic workshops.

Inside these facilities, technicians—sometimes fellow prisoners trained under supervision—worked on artificial limbs designed to restore mobility and independence. These were not crude or symbolic devices. They were functional, adjustable, and carefully fitted.

For disabled German POWs who had assumed their injuries would define the limits of their future, the sight was overwhelming. Many had never imagined walking again with stability, let alone being encouraged to do so.

Some wept openly. Others stared in silence, unsure how to process what they were being offered.

Work Matched to Ability, Not Punishment

Work assignments existed in the camps, but they followed a logic unfamiliar to many prisoners.

Disabled POWs were not forced into labor they could not physically perform. Instead, tasks were matched to ability: administrative work, maintenance, repair, teaching, clerical assistance, and workshop roles.

The purpose was not humiliation.

It was contribution.

This distinction mattered deeply. Work was framed as participation, not punishment. Men who had believed themselves useless found ways to remain engaged and valued.

For many, this restored something more important than income or routine—it restored self-respect.

Witnessing How Americans Treated Their Own Wounded

One of the most profound moments for many German POWs came not from how they were treated, but from what they observed.

They saw American wounded veterans—men missing limbs, using wheelchairs, or recovering from severe injuries—treated openly and respectfully. These soldiers were not hidden away. They were not shamed. They were honored.

Disabled Americans were saluted.

They were spoken to with respect.

They were included, not erased.

This directly contradicted years of indoctrination that equated injury with weakness and shame.

The Collapse of a Dangerous Myth

Many prisoners later said this was the moment something inside them broke—not physically, but mentally.

They had been taught that strength meant perfection, endurance without complaint, and sacrifice without vulnerability. Injury was failure. Dependency was disgrace.

Yet here was a system that treated injury as part of human reality—not a moral flaw.

Strength, they began to realize, could include care.

Dignity could exist alongside limitation.

Respect did not require wholeness.

Conversations That Changed Perspectives

Over time, conversations emerged—often quietly, sometimes awkwardly—between prisoners and guards, doctors, or civilian workers attached to the camps.

Disabled POWs asked questions they had never dared to ask before:

Why are we treated like this?

Why are your wounded not hidden?

Why does care matter so much?

The answers were rarely dramatic. Often, they were simple:

“Because this is how it’s done.”

“Because everyone deserves it.”

“Because war already takes enough.”

Those answers lingered.

The Psychological Impact of Being Seen

For many disabled prisoners, the greatest shock was not the physical care—it was visibility.

They were not ignored.

They were not spoken about as problems.

They were addressed directly, asked for input, and expected to recover as fully as possible.

This sense of being seen had a powerful psychological effect. Men who had withdrawn into silence began engaging again. Some resumed writing, teaching, or mentoring younger prisoners. Others spoke about futures they had once assumed were gone forever.

The camps, unexpectedly, became places of rebuilding.

Captivity Without Dehumanization

None of this meant captivity was pleasant or easy. Prisoners remained prisoners. Freedom was limited. The future was uncertain. Homes were far away, and families were often unreachable.

But there was a crucial difference: captivity did not equal dehumanization.

Rules were enforced without cruelty.

Discipline existed without humiliation.

Authority functioned without terror.

That distinction changed everything.

Realizing Propaganda Had Failed

Over time, many disabled POWs came to an uncomfortable realization: much of what they had believed about their enemies had been false.

Not exaggerated.

Not misunderstood.

False.

The idea that compassion was weakness.

The belief that dignity only belonged to the strong.

The assumption that mercy could not survive war.

All of it collapsed under daily experience.

Quiet Reflections on Identity and Responsibility

As months passed, prisoners reflected deeply on what they had witnessed. Some struggled with guilt. Others with anger at having been misled. Many felt grief—not only for what they had lost physically, but for years shaped by distorted values.

Yet alongside that pain emerged something else: clarity.

They had seen another way of organizing power.

Another way of defining strength.

Another way of treating the broken without discarding them.

That knowledge stayed with them.

Release and the Weight of Memory

When the war ended and prisoners were eventually released, disabled German POWs returned to a country devastated economically, socially, and morally.

Many carried prosthetics fitted in captivity.

Many carried habits learned there—structure, cooperation, self-advocacy.

All carried memory.

Some spoke openly about their experiences. Others stayed silent, unsure how to explain kindness received from an enemy to those who had not witnessed it.

But none forgot it.

Why This Story Was Rarely Told

Postwar narratives favored extremes: cruelty and heroism, guilt and innocence, victory and defeat.

This story existed in the uncomfortable middle.

It showed humane treatment in a time defined by inhumanity.

It complicated identity.

It challenged convenient myths.

So it survived mostly in private testimony, letters, and quiet recollections rather than official histories.

What Disabled POWs Learned About Humanity

Years later, many former prisoners would say the same thing:

“They treated us like men, not symbols.”

That distinction mattered more than any ideology. It reshaped how they understood responsibility, power, and care.

They had expected punishment.

They had encountered dignity.

And that contrast stayed with them for life.

Why This Story Still Matters

Today, wounded veterans, prisoners, and displaced people still face systems that struggle to balance security with compassion.

This story matters because it shows that dignity is not a luxury of peace.

It is a choice—even in war.

It proves that how societies treat the broken reveals more about strength than how they treat the powerful.

Compassion as Quiet Resistance

In American POW camps, compassion was not dramatic. It did not announce itself. It functioned through routines, workshops, medical charts, and respectful language.

But that quiet consistency dismantled years of conditioning.

It revealed a truth more powerful than propaganda:

Humanity does not disappear in war unless people choose to let it.

The Shock That Lasted a Lifetime

Disabled German POWs entered captivity expecting cruelty.

They left having witnessed something far more unsettling—and transformative.

They saw that even in the shadow of destruction, compassion could operate without apology.

And for many, that realization changed not just how they remembered the war—but how they chose to live afterward.

Sometimes, the most shocking weapon in war is not force.

It is dignity, offered where none was expected.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.