- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- (1943) Female Italian POWs Thought Americans Were Myths—Then They Met Loggers, Miners and farmers. VD

(1943) Female Italian POWs Thought Americans Were Myths—Then They Met Loggers, Miners and farmers. VD

(1943) Female Italian POWs Thought Americans Were Myths—Then They Met Loggers, Miners and farmers

The Women Who Saw America: A Journey of Discovery

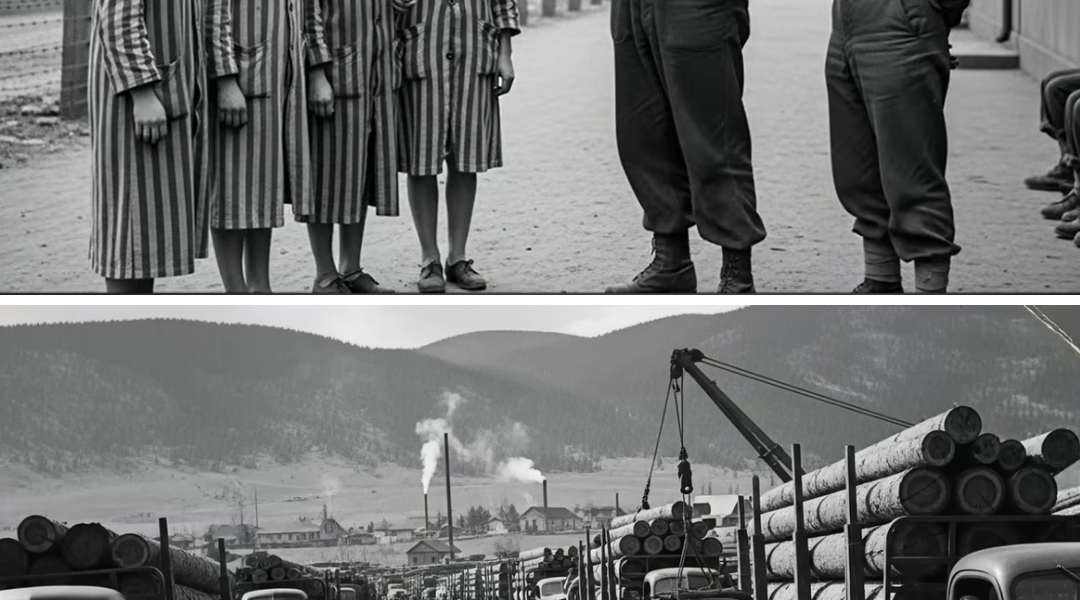

On April 17, 1943, Maria Ki, a 26-year-old Italian nurse, stood frozen at the entrance of the mess hall at Fort Missoula, Montana. It had been a month since her capture during the final days of the Italian campaign in North Africa. She and other women had been captured while serving in support roles for Mussolini’s ill-fated campaign, and they were now prisoners of war on American soil. Maria’s mind raced, trying to reconcile what she was seeing with everything she had been taught.

Before her lay an American breakfast – three eggs, four strips of bacon, toast with real butter, fresh coffee with sugar, and a glass of orange juice. This wasn’t just a meal; it was a revelation. In Italy, under wartime rationing, the average family barely had enough to survive. Meat was a rarity, fruit was a distant memory, and sugar was almost entirely gone. Yet here she was, a prisoner of war in a foreign country, served a breakfast more luxurious than anything she had experienced in years.

Maria turned to her fellow prisoner, Akiko Yamamoto, and whispered, “They told us American men were weak, stunted creatures, barely capable of standing upright. This isn’t possible.” Her voice trembled as she tried to comprehend the enormity of what she had witnessed. She had been taught that Americans were physically inferior, suffering from poverty and deprivation. The reality she now faced shattered everything she had ever believed.

As she slowly sat down at the table, she noticed the American soldiers serving food with casual ease. One of them, a young man from Montana, smiled at her and pushed a plate toward her, saying, “There’s plenty more, ma’am.” The calm, unhurried way he offered this bounty only made it more surreal. Maria thought to herself, How could this be? The contrast was so stark it was impossible to ignore.

What Maria experienced in that moment was only the beginning of her journey, one that would lead her and her fellow prisoners to a profound ideological awakening. Maria and the other Italian women had been brought up on a diet of fascist propaganda, taught to fear and despise America as a crumbling, inefficient nation. They had been told that America’s industrial capacity was a myth, that their factories were inefficient and their people weak. The reality, however, would be much harder for them to ignore.

The American industrial power that greeted Maria and the others at Fort Missoula was beyond anything they had ever imagined. The first shock came in their journey across the Atlantic. Despite being enemy prisoners, they had been transported in comfort. They traveled in passenger trains with upholstered seats, regular meals, and even occasional stops where fresh fruit was handed out to them. To the Italian women, this seemed impossible. In Italy, civilians had been subjected to severe rationing, and ordinary people couldn’t afford to travel, let alone enjoy such luxuries.

When they arrived at the camp, the surprises kept coming. Fort Missoula was not the grim prison camp they had anticipated. Instead, it looked more like a small town, with barracks converted to dormitory-style housing, recreational facilities, and even a well-stocked library. The camp was surrounded by a simple fence, not the barbed wire and guard towers they had expected. When one of the senior officers inquired about the camp’s apparent lack of security, the American commander, Colonel James Whitam, casually replied, “You’re in Montana. Even if you escaped, where would you go?” He continued, “You’ll find that well-fed, respectfully treated prisoners rarely try to escape.”

This was not the treatment they had been led to believe prisoners received in America. These prisoners were treated with a level of respect and care that defied their understanding. They had expected to be starved, beaten, and humiliated, but instead, they were offered medical treatment, food, and care. They were given daily access to food that exceeded what they had been told about American deprivation.

As the women worked on agricultural projects or in local businesses, they were exposed to everyday American life. They witnessed an abundance of resources that had once been a distant fantasy to them. Giana Espazto, a 23-year-old former radio operator, had been assigned to work in a large apple orchard in the Bitterroot Valley. Her first experience in the orchard left her reeling. “They gave us these wooden crates to fill with apples,” she wrote. “I was being very careful, making sure not to bruise any fruit. The American foreman came over and asked why we were being so cautious. When I explained that in Italy every piece of fruit was precious, he laughed and said, ‘Honey, these are just processing apples for applesauce and juice.’”

To Maria, this revelation was more than just about food. It was about the contrast between the lives she and her fellow prisoners had been told to lead and the way they were now treated. She realized that the abundance of food, the access to resources, and the ease of life here were all things that had been denied to her, her family, and her country for years. The disparity was too vast to ignore.

More startling realizations followed. They began to understand the scale of American production that had fueled the war effort. American factories weren’t just producing tanks and planes; they were producing food and supplies at a scale that was beyond comprehension. Rosa Bellini, a former logistics officer, couldn’t help but be astounded by the sheer numbers of products being shipped across America. “They discarded more edible food in a day than my entire village would consume in a month,” she wrote. In Italy, food was precious. They had been taught that America’s industry was inefficient, but what they saw before them defied that claim.

The real breaking point came when they discovered the everyday items the American soldiers and workers had access to. Francesca Rizo, a seamstress, had been working at a local dry-cleaning business. She was astounded by the clothes brought in by the workers. “These men, who perform physical labor, own multiple suits, shirts of fine cotton, and leather shoes. I had only seen such things worn by government officials in Rome,” she wrote. When she asked her supervisor if these belonged to the wealthy elite, she was told, “No, dear. These are the working people of Missoula.”

That was when it all clicked for the women. The ideology they had been taught about America was completely false. These weren’t just wealthy elites flaunting their abundance. These were ordinary working-class people who lived better than the upper class in Italy.

Their ideological journey culminated in their understanding of the American way of life: not just the abundance of goods, but the sense of opportunity that accompanied it. They learned that Americans didn’t just have more, they had more because of their system. The American democracy, which they had been taught to despise, had created a society where even the poorest worker had access to comfort and security.

As the war ended, the psychological transformation of these women continued. Many of them, like Maria Ki, chose to stay in the United States after the war. They were no longer prisoners but witnesses to a reality they had never believed possible. They had come to America expecting to find weakness and inefficiency, but they found strength and abundance instead.

Maria Ki, who had once stared in disbelief at her first American breakfast, later opened a small Italian restaurant in Missoula. When asked about her time in America, she would smile and tell customers, “I came to America expecting a nation of contradictions. What I found instead was a nation where ordinary people lived better than our elites. That discovery changed everything I believed about the world.”

The transformation of these women wasn’t just about changing their minds about food, but about reimagining their country’s place in the world. The myths that had sustained their nationalism for so long crumbled in the face of undeniable evidence. The war, in the end, wasn’t just about tanks and planes. It was about the power of a society that could produce more than its enemies, and more importantly, about the freedom to share that abundance with everyone.

By the time Italy officially surrendered and joined the Allies, the women of Fort Missoula had experienced something more powerful than victory: they had seen firsthand the strength that comes from abundance, and they would never look at the world in the same way again.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.