German POWs Couldn’t Believe Their First Day In

The Quiet Defeat

August 4th, 1943, Norfolk, Virginia. The Liberty ship groaned like an old beast exhaling its last breath, metal scraping against metal as it docked. Wilhelm Krauss stood among hundreds of German prisoners of war, their uniforms ragged, faces blackened with soot and hollowed by the sea. The air carried the sharp tang of salt, mingled with engine oil and the faint, taunting aroma of fresh bread from a nearby bakery. Wilhelm’s stomach clenched—not from hunger alone, but from the fear coiled tight in his gut. German slogans echoed in his mind: America is barbaric. They will break you. Better dead than captured.

He gripped the icy railing, each step down the gangplank a battle against the dread he’d carried for months. From Munich to the African Corps, he’d been drilled to expect cruelty—rifle butts, insults, the savage barbarity of the enemy. But as his boots hit the pier, something shattered his expectations. Laughter. Real, unguarded laughter from American soldiers lounging in groups. One flicked open a Zippo lighter, the sharp click cutting through the humid air. Another chewed a sandwich, the smell of cold cuts and soft bread drifting like a cruel tease.

Wilhelm froze. In his mind, America was a skeletal ruin, wind-scoured and barren. Yet before him stood white church steeples catching the dawn light, intact rooftops, freshly painted trucks rumbling along the road. Live oaks cast long shadows over the street, their leaves trembling softly. The Americans weren’t seething with hatred; they were relaxed, human. One MP sipped coffee and smiled as the prisoners passed. Wilhelm’s heartbeat stuttered. Everything he’d believed cracked under the weight of this impossible reality.

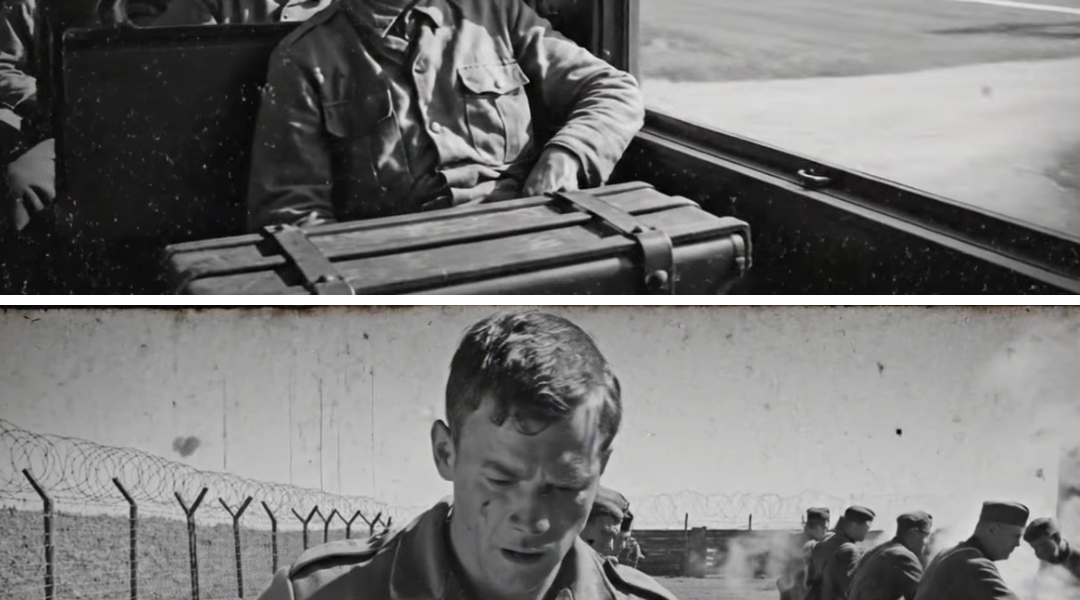

The military truck growled to life, shuddering like a waking beast, and rumbled away from the pier. Wilhelm pressed against the wooden bed, arms wrapped around his knees, breaths shallow as if loud breathing might invite a blow. But no one struck. Inside, the air was thick with clashing scents: hot iron from the truck, sea salt on their clothes, sour sweat from below decks—and then, slicing through it all, the smell of bacon and warm bread. The American soldiers ate breakfast casually, tearing into sandwiches wrapped in wax paper. The aroma of cold cuts, butter, and fresh bread flooded the cramped space, tightening Wilhelm’s stomach like a vice.

In Germany, they’d eaten hard black bread that tore gums. In America, even breakfast smelled like a holiday. He tried to turn away, but the scent clung, mocking him. A train whistle cried in the distance, rising over the morning air, mixing with birdsong—sounds so peaceful, so untouched by war’s jagged edges. Wilhelm had seen rubble across Europe, but as the truck rolled through Norfolk’s cobblestone streets, he glimpsed intact homes, white steeples, and the broad shadows of live oaks swaying gently. This wasn’t the ruined, starving country German newspapers had painted. It unsettled him more than anything.

The truck rattled over potholes, knocking prisoners together. Wilhelm squeezed his knees tighter. The wood was rough but warm, nothing like the damp boards of German wagons. Every detail heightened his unease—too clean, too orderly, too normal. An American MP glanced back, and Wilhelm’s head dropped instantly, cheeks burning. But the soldier simply asked his buddy, “Hey, you want the last one? Bacon’s still warm.” The sandwich passed forward with a crackle of wax paper. No one guarded them nervously; no one treated them like threats. Why? Wilhelm swallowed hard. His mind split: one part clung to propaganda’s lies, the other whispered a terrifying suspicion that he’d been deceived for years.

The road widened, lined with green trees. The sea’s salt faded, replaced by damp earth. A soft breeze carried flour from a roadside bakery. In Europe, such smells heralded death and ruin; here, they signaled life. The truck stopped at a light. From a nearby neighborhood, Wilhelm heard children playing baseball—the crack of wood on ball, bursts of cheering. The sound pierced him like a needle. War had ravaged Europe, but America seemed whole, healthy. Why aren’t they suffering? Why aren’t they starving like we were told? Why does everything look alive?

The truck lurched to a full stop before a tall iron gate. Wilhelm’s heart pounded at the hiss of hinges—a sound too familiar, usually followed by barked orders and the stripping of humanity. When the Americans ordered them out, he moved in a daze. But the first scent that hit him wasn’t hostility—it was food. A wave of warm air carried fried chicken, fresh bread, and melting butter straight into his face. It struck so hard he stumbled. In German barracks, good food was for officers only; in European camps, prisoners got black bread and watery soup. Here, a prison camp smelled like a family kitchen.

He looked around: rows of white-painted wooden barracks, clean windows, new tin roofs—no damp darkness, no rotting trenches, just pinewood and morning earth. The Americans nearby didn’t glare; one wrote on a clipboard, joking with his buddy, both laughing openly. No one gripped rifles like they awaited an excuse to strike. A black MP smiled at the prisoners’ confusion. Wilhelm lowered his gaze, afraid to return it, still believing any misstep brought punishment. But none came. One soldier pointed to a long building: “Straight inside, gentlemen. Breakfast is almost ready.” Breakfast. The word nearly made Wilhelm laugh, his throat too dry for sound.

He stepped into the mess hall, his heartbeat slowing. Long wooden tables, a spotless floor, natural light pouring in, a faint trace of disinfectant. It looked more like a training barracks than a detention center. In the middle, steaming trays of golden fried chicken, mashed potatoes, warm biscuits, and strong black coffee. The German prisoners stood frozen, convinced this was psychological warfare. An American cook, hair silvered at the temples, looked at Wilhelm and nodded a greeting. No disdain, just a gesture from one human to another. He placed a tray into Wilhelm’s hands as if offering something profound. “Eat it before it gets cold,” he said. The words hit like a blow to the chest—simple, shattering the propaganda shell. In Germany, prisoners were shouted at; here, the cook called him son.

Wilhelm looked down at the hot food, steam warming his face, the rich smell of meat and soft bread colliding with memories of hunger. He wanted to eat immediately, but his hands trembled—not from hunger, but disbelief. A whisper from beside him: “The Americans are really feeding us.” Wilhelm couldn’t answer. He walked to the table, set his tray down, and sat on a clean wooden chair, hesitating to rest his hands. No shouting, no fists, no degradation. For one fragile second, he felt human again—not war debris, but a man.

When he lifted his fork, the smell of fried chicken rose anew. It wasn’t the food that overwhelmed him; it was the unearned kindness radiating from people he’d been taught to hate. Standing at the gates of an American camp, Wilhelm realized the most terrifying truth: America didn’t act like a ruthless victor. It acted like human beings—and that broke him deeper than any weapon could.

Night fell over the camp faster than expected. The Virginia sky shifted to deep violet, then darkness. As guards led them to the barracks, Wilhelm walked with a feeling of stepping into a trap woven from daytime kindness. Everything had been too strange, too illogical, tightening him like a drawn bow.

The barracks door opened, and Wilhelm froze. Wide, airy rooms lit by warm yellow lamps, a soft trace of laundry powder in the air—a scent he’d never smelled in German barracks, where moldy blankets and damp straw were the norm. What paralyzed him were the long rows of beds: each with a real mattress, thick and springy, covered by a crisp white sheet, a pillow neatly at the head. At the foot, a light blue cotton blanket, folded like by an American mother. Wilhelm’s mind went blank. In Europe, soldiers slept on straw or planks; in Tunisia, on hot, dry ground. Here, in an American camp, they got real beds.

A prisoner muttered, “Will there be inspections? Or is this how they get us to drop our guard?” Wilhelm didn’t answer. He stepped toward his bed, laid a hand on the mattress—it dipped softly, luxuriously. A sensation so overwhelming, heat rose under his skin. No, this couldn’t be real. This had to be a performance. But sitting down, the mattress embraced him, muscles surrendering to softness for the first time in months. The clean cotton smell tightened his throat—a gentle scent belonging to life, not war or fear.

Outside, Virginia’s night insects hummed, live oaks rustled in the wind. No gunshots, no screams, no marching boots—only peaceful night, unsettling in its completeness. A prisoner trembled nearby, not from cold, but overload. Wilhelm understood. The fear wasn’t of punishment or hunger; it came from realizing Americans weren’t the monsters painted by Germany. He pulled the blanket over himself, catching faint smells of dry grass, laundry powder, and lemon cleanser—none belonging to hatred. And in that moment, he realized the most shameful truth: he didn’t know how to face kindness. He’d been trained for bullets and barracks, hunger and fear. But in an American camp, treated like a human, he had no idea what to do with the emotions rising inside him. Before sleep, he thought, Kindness is the enemy I never learned to fight. Yet he slept on the softest mattress ever, not because America humiliated him, but because that was simply how Americans treated people.

Morning crept in quietly, as if light feared disturbing overturned worlds. Wilhelm awoke to an unfamiliar sensation: no back pain. The sheet was cool and clean, carrying laundry powder’s scent. The pillow cradled his head—a luxury unknown in the German army. He lay still, unable to understand. No one could.

The door opened, footsteps soft. Then the smell of clean cotton and fresh pine drifted in. Wilhelm jerked upright, heart tightening. He expected inspection, shouts, hatred’s reappearance. But the American carried books. No guns, just books. A prisoner whispered, “What do they want?” No answer. The soldier placed a thin brown-covered book on each bed. Wilhelm recognized the scent: paper, a peaceful smell in a war-torn world.

When the book landed before him, he saw two words: Holy Bible. He froze, mind stepping into forbidden territory. The American smiled, slow and gentle. “Not to convert you,” he said. “To give you peace.” Peace? A trivial word, yet it struck like a stone on frozen ice. In German barracks, they taught honor, victory, death. No one taught peace. The American sat beside his bed—no force, just two men talking as if war didn’t exist. “Your mother back home—she probably prays for you. Ours do too.”

Wilhelm wanted to reject it, pull away, protect the Reich’s armor. But that ordinary sentence pierced him—mothers. Germans had mothers; Americans did too, all worrying for sons on either side. He swallowed, throat tightening painfully. He couldn’t look longer, fearing he’d break. The American rested a hand on the book. “Keep it. You’ll need something that helps you sleep.” He stood, moving on gently.

Wilhelm opened the book. The first page lifted with old paper’s scent, dust, and memories of bomb-free homes. Morning light struck the text: Blessed are the peacemakers. He read again and again, each word hammering propaganda’s walls. Last night, he’d lain awake fearing kindness; this morning, he feared facing it. He’d been prepared for hatred, found understanding. Punishment became compassion. Sitting with the Bible, he realized a truth more frightening than artillery: Guns broke bodies. America broke something deeper.

He closed the book and stood. Pine rose warm from the floor. A breeze slipped through the window, carrying damp earth and flour from the kitchen. Not war’s smell, but life’s. He stepped outside. Golden light spread across the yard. Wind brushed barbed wire, barbs glinting silver—not a weapon, but shimmering. Beyond, town church steeples rose through trees. On this side, live oak shade stretched cool and calm.

Everything contradicted his beliefs. In Germany, they said America was barbaric; here, soldiers smiled and called him fellow, a word for humans. Godless? Yet a Bible in his hands, for peace, not conversion. Each truth was a stone cracking the Reich’s wall. Wilhelm looked around. Prisoners lined up for breakfast. No shouting, no striking. Some smiled thinly, needing war’s permission for joy. A guard called, “Breakfast’s ready. Coffee, too.” Coffee—a myth in frontline stories, now served to prisoners.

Wilhelm went still. He’d fought monsters, found people. He could no longer deny it. An MP flicked his Zippo—click—once startling, now ordinary. The guard nodded politely, without malice. Wilhelm returned it, a small nod feeling like a new language: respect. Something softened inside. He stood, watching sunlight on wire, smoke from kitchen, live oak leaves shimmering. Then he understood: They weren’t reforming him, weren’t proving anything. They simply lived their beliefs—even enemies deserved humanity. And that broke him deeper.

He drew a breath—earth, flour, morning air—then stepped toward the mess hall line. At that moment, he knew: Nazism told us America was a monster. But America defeated that lie with something more powerful than force. Decency.

Wilhelm stepped in, smells hitting harder: baking bread, crisp and soft; bacon frying, smoky; real coffee. In Germany, mornings smelled of gunpowder and mold; here, like family. He hated missing it. A prisoner whispered, “They’re feeding us this again every day.” Wilhelm didn’t answer—the truth lodged in his throat. They fed them well, as if unremarkable.

Sounds differed too: chair scrapes, spoon taps, guard laughter, Zippo clicks—soft, confident, unafraid. Wilhelm sat on a steady chair, floor polished enough to reflect his hand. Fork touching bacon, he stopped. Hands trembled—not hunger, but emotion. He’d eaten American food, but never enjoyed it. Today, he couldn’t resist.

He took a bite. Salt, smoke, crispness exploded. Time stopped. Germany lacked this taste; war lacked it; hatred lacked it. He set the fork down, inhaled deeply, heartbeat stumbling. Dizzy, unsteady—not from goodness, but letting America in, not stomach, but beliefs.

An American placed water jugs, nodded: “Breakfast’s good today, huh?” No answer. Wilhelm’s throat tightened with unexplained emotions. He’d seen Americans as monsters. But monsters don’t feed prisoners, share coffee, treat enemies humanely.

Breakfast ended. A prisoner whispered, “Maybe they want us dependent.” Wilhelm shook his head. “No, this wasn’t control. This wasn’t manipulation. This was how Americans lived, treated people, believed—and that terrified him more than weapons.”

Stepping out, he felt light—not joyful, but uncurled, no longer cornered. That unsettled him. He glanced back; bacon and bread clung to his clothes like a kitchen exit. Not a camp. None fit his taught image. Prisoners weren’t treated this way, but he experienced it, forcing inward look.

Across the yard, prisoners clustered cautiously. No laughter, no deep breaths, no comfort, though nothing threatened. Wilhelm heard Zippo click by the gate. Yesterday, flinch; today, cigarette lighting. “Why standing still?” a prisoner asked. Wilhelm paused. “I don’t know what to think anymore.”

A child’s laugh echoed beyond the fence—the boy from yesterday, holding a baseball. His father walked beside, newspaper tucked. Casual, uncurious, as if prisoners were passersby. Wilhelm watched longer than intended, jealous. In Germany, children lacked such mornings—no baseball, no laughter, no childhood. Suddenly, he understood: America wasn’t as told, never collapsed like Germany.

He walked to the fence, hand on barbed wire—cold, dry, no longer frightening. One day earlier, the other side held waiting enemies. Today, life—real, ordinary, uncalculated. He inhaled deeply: salt air mixing with clean cotton from sheets. Too clean, too calm, too different. He couldn’t process it.

An MP set a water container, glanced: “You good?” Not mocking, just human question. Wilhelm nodded, unsure. As the soldier walked away, he understood: Americans didn’t think it special. Kindness to prisoners was right—no philosophy, no agenda, just instinct. Harder to face than anything.

He sat on dusty ground near barracks, hands on knees, eyes on boots—dirty, worn, Sahara mud opposite polished American boots. Change came not from speeches, but small things: a nod, steadying a fall, bacon strip, dawn Bible, playing child. Gentle, undefendable. Not converted, not broken—shown unseen humanity. Truer than propaganda.

He spoke softly: “If this is the enemy, maybe I’ve misunderstood my life.” No drama, just a man in a yard, hatred losing grip.

Wilhelm nearly slipped into sleep when a soft thump sounded outside. Not urgent, just something placed gently on the step. He sat up, moved to the window. Moonlight showed an American soldier walking away, leaving a small tin box. No request, no ration—just spontaneous. Wilhelm stepped out, picked it up. Inside, apple pie slice, warm, wrapped in wax paper. No note, just pie in the night.

He stood frozen. Wartime rations made it foreign—too homelike, too ordinary, too kind for a rifle-pointer. He lifted it; warmth seeped through fingers. Apple, butter, cinnamon mixed with wind. A bite, and he sat on the step, legs failing under rising emotion. Armor fell.

He remembered the catcher, baseball toss, soft mattress, clean smell, “You good?” Bible, non-monster eyes. Tonight, pie—the final drop. He understood: no longer dock-stepper. A pie told what war couldn’t. America’s everyday kindness, unperformed, uncalculated, stronger than propaganda.

Gripping the box, moonlight tracing wire, he realized it no longer barred—just bordered old beliefs and new life. He whispered, “No one told me America could be this gentle.”

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.