You Want Us To Eat WHAT Female German POWs Were CONFUSED When They Got Served Hotdogs. VD

You Want Us To Eat WHAT Female German POWs Were CONFUSED When They Got Served Hotdogs

The Meal That Changed Everything

June 18th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas.

The heat arrived before the guards did. It pressed down on the wooden tables, on the gravel beneath our shoes, on the backs of our necks, where sweat gathered and refused to dry. Texas heat did not rush or shout. It settled in slowly, confidently, like it knew it belonged there.

We were marched into the open-air mess area just before noon. No walls, no ceiling, just long wooden tables, rough benches, and a serving line set up under a tin awning that shimmered in the sun. The smell hit me first. It was unlike anything I had expected. Not soup, not boiled potatoes, not the thin gray steam of wartime kitchens. This was different.

Hot fat. Soft bread. A faint curl of smoke drifting lazily upward, carrying something rich and unfamiliar with it. My stomach tightened, not with hunger, but with confusion.

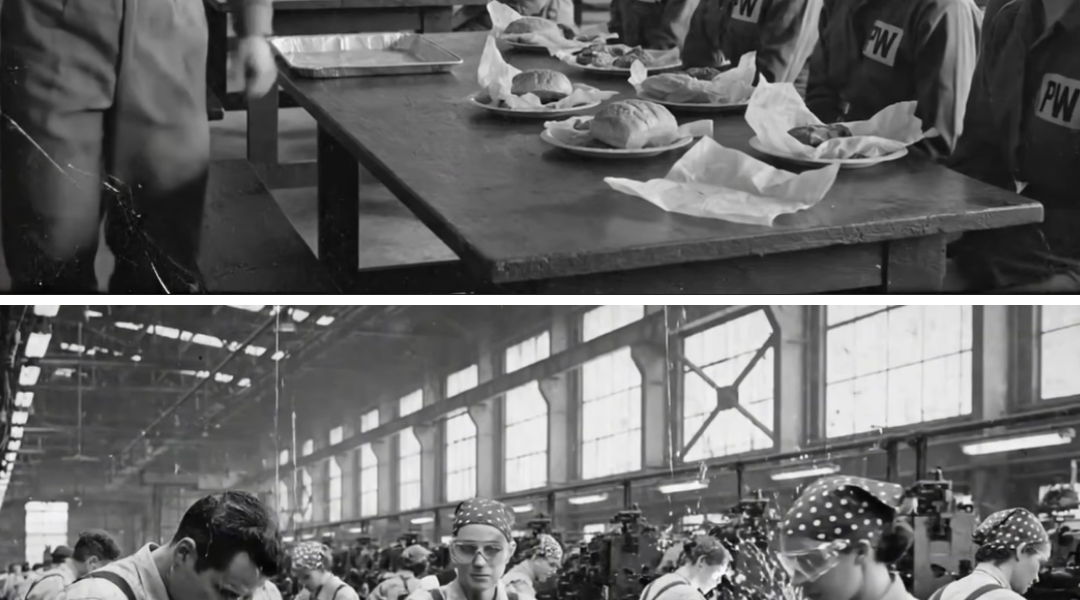

When my turn came, the sound reached me before the sight. Metal on metal, a tray sliding forward, a dull clang as something was placed onto it. I looked down. A long, pink sausage rested inside a split white roll. The bread looked impossibly soft, pale as fresh paper. It was wrapped loosely in waxed paper, the edges already turning translucent where grease had soaked through. No knife, no fork, no plate—just this.

For a moment, I genuinely thought there had been a mistake. I lifted my eyes to the American soldier behind the counter. He was young, barely older than my brother had been before the war took him. His sleeves were rolled up. His posture was relaxed. He was chewing something himself as he worked, jaw moving slowly, casually.

“Hot dog,” he said, as if naming a common object, as if I were standing at a fair, not in a prisoner of war camp.

“Hot dog.” The words meant nothing to me. I carried the tray to the table and sat down.

Around me, other German women did the same, lowering themselves onto benches with the careful stiffness of people who expected something bad to happen at any moment. No one spoke at first. We stared at the bread, at the sausage, at the grease pooling faintly in the paper.

Finally, someone whispered behind me, barely audible, “Is that food?”

I thought the same thing. In Germany, even at the worst moments of the war, food had rules. There were lines. There were portions. There were utensils. Even when there was little else, you sat, you waited, you ate carefully. This thing in front of me demanded none of that. It required hands.

Across the table, I saw an American guard lean against a post. He held the same thing I did. He lifted it without hesitation and bit straight into it, teeth sinking through bread and meat in one motion. He smiled at something another guard said, grease shining briefly at the corner of his mouth.

I felt my chest tighten. This was not how prisoners were fed. This was not how enemies behaved. I had prepared myself for cruelty, for shouting, for humiliation, for being reminded in a hundred small ways that we had lost. But no one was shouting. No one was watching us closely. No one seemed afraid of us. The guards talked among themselves. One laughed. Another wiped his hands on a cloth tucked into his belt. A third reached for a bottle of water and took a long drink, tilting his head back toward the sun. They ate like men on a lunch break.

That was the shock. Not violence, not punishment—normality.

I did not lift the food. I could not. Years of instruction pressed against my mind, sharp and insistent. We had been warned about Americans, about their lack of discipline, about how they treated prisoners, especially women. They would break you first, we were told, slowly, casually, with smiles. This had to be the beginning of that.

I looked around the table. Greta sat rigidly, hands folded in her lap, eyes fixed on the bread as if it might move on its own. Another woman nudged her tray slightly away as though distance might protect her.

“Eat,” someone whispered. “Before they make us.”

But no one made us. Minutes passed. The heat hummed softly around us. Flies drifted lazily near the tables. Somewhere beyond the fence, a truck engine coughed and then settled into a steady idle. The world did not hold its breath. Nothing dramatic happened. In Europe, men were dying by the thousands on the beaches of Normandy. Entire cities were shaking under bombs. The war was swallowing everything it touched.

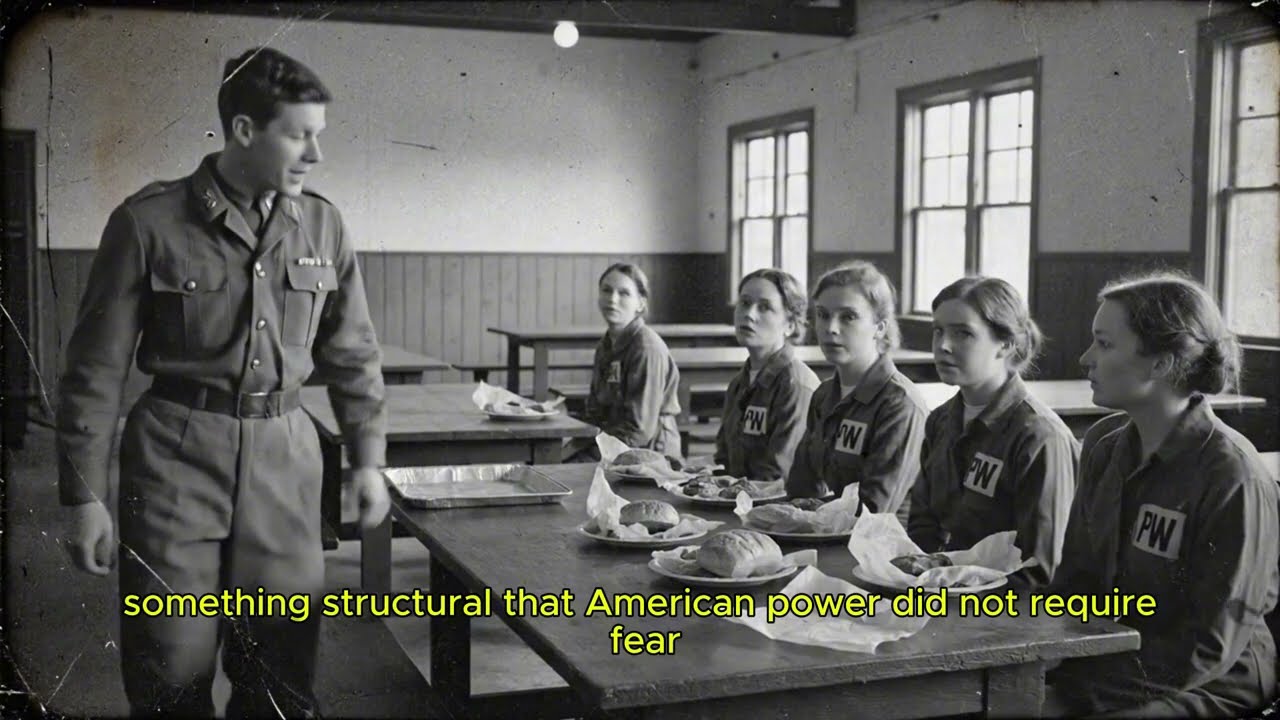

And here in Texas, the smell of cooked meat drifted freely through the air. I did not know it then, but this place existed because of something larger than kindness alone. America was producing at a scale we could barely imagine. Liberty ships slid into the ocean faster than they could be sunk. Factories turned out bombers by the hour. Trucks, uniforms, rifles, boots—everything in numbers that felt unreal. And food. So much food that even prisoners received it without ceremony. Texas ranches stretched farther than my eye could follow. Cattle in numbers that made no sense to someone raised on ration cards and shortages.

White bread was not a luxury here. It was ordinary.

But sitting at that table, I knew none of this. I knew only what I saw. Men who did not fear us. Food that was not guarded. An enemy who ate the same meal we were given. My fingers trembled slightly as I reached for the waxed paper. It felt warm. Grease touched my skin. Real grease, not watery soup sheen, but something thick and alive. I flinched, surprised by the sensation.

This, I thought, is not meant to be eaten politely. This is meant to be eaten.

I hesitated, the question forming in my mind before I could stop it. You want us to eat this? Not with permission, not with gratitude—just eat.

That was when I realized something unsettling. For the first time since my capture, no one was trying to control my fear. And somehow, that frightened me more than cruelty ever could. Because it meant this moment was real. And if this was real, then everything we had been taught about America might not be. Not even close.

They told us this was how humiliation began. No one touched the food. That was the strangest part. The hot dogs lay on the trays, steaming faintly in the Texas heat, untouched, like props, waiting for a cue that never came. The Americans kept eating, laughing, talking about things we could not understand, and still no one said a word to us. That silence felt deliberate.

I sat there with my hands resting flat on my thighs, back straight, eyes forward, every muscle in my body trained to wait for the moment when kindness would turn into something else. Because this—this calm—was exactly how we had been warned it would begin. We had been trained for this long before capture. Not formally, not always in classrooms, but steadily, relentlessly through repetition, through radio broadcasts that crackled through barracks walls at night, through posters pasted near train stations and factory gates, through short films shown before news reels, always smiling, always confident in their message. The Americans, we were told, lacked discipline. They were loud, undignified, overfed, a nation without culture, without restraint. They mistook abundance for strength and softness for morality. And prisoners, especially enemy prisoners, were not to expect dignity. Humiliation, our instructor had said, was their favorite weapon. They would strip you of ceremony first, then of habit, then of self-respect. Food, they warned, would be part of it. They would make you eat like animals with your hands, without order, without shame.

Sitting at that wooden table in Camp Hearn, Texas, I felt those words tighten around my chest like wire. Because what I was seeing matched the warning too well.

In Germany, even hunger had rules. I remembered dining halls back home, long before the war had devoured everything. White tablecloths, even if they were patched. Cutlery aligned carefully beside plates, the expectation that you sat upright, chewed quietly, waited until everyone had been served. Later, when food grew scarce, the rituals remained. There might be less bread, thinner soup, fewer potatoes, but there was still order, still structure, still the idea that how you ate mattered, even when what you ate barely sustained you. It was one of the last things that made us feel human. Here, none of that existed.

The Americans leaned on tables. One guard sat sideways on a bench. One foot propped up casually. Another wiped grease from his fingers onto a napkin and tossed it away without looking. They did not lower their voices in our presence. They did not pause when they laughed. They did not perform restraint for us.

And that, more than anything, terrified me. Because if this was intentional, if they meant to show us that manners, ceremony, and order no longer applied, then what came next would be worse.

I imagined it clearly. First, they would make us eat this way. Then, they would watch, then they would laugh. They would say, “Look how quickly you forget who you were.” That was the humiliation we expected.

Across from me, Greta’s fingers curled tightly into her skirt. I could see the pulse racing in her neck. She leaned slightly toward me and whispered, barely moving her lips.

“Don’t touch it yet.”

I nodded. Not eating felt safer than eating. To refuse was to hold on to something. Control, choice. The last thin line between us and whatever this was meant to become.

Time stretched. The Texas sun climbed higher. Sweat traced slow lines down my spine. A fly landed on the edge of my tray, tasted the grease, and flew away again, unimpressed. Still, no one spoke to us. Still, no one ordered us.

That too had been predicted. They will pretend not to care, the radio voice had said years ago. They will make you think you still have freedom until you realize too late that you do not.

I forced myself to look beyond the table, past the guards toward the camp fence. Beyond it lay a world untouched by bombing. No shattered buildings, no blackened walls, no broken windows stuffed with rags, just flat Texas land shimmering in the heat. Somewhere in the distance, I could hear the steady rhythm of machinery, work, production, life continuing without interruption, while Europe burned.

That contrast lodged itself in my mind, sharp and painful. In France, cities were being pulverized. In Germany, families huddled in shelters as sirens wailed through the night. Coffee was a memory. Meat a rumor. White bread, something you dreamed about and then forgot. And here, here, kitchens ran on schedule. Meat was cooked openly. Bread was sliced generously. Coffee, I would later learn, was brewed every morning without ceremony or apology. Not as a display, not as a message, just as routine.

At the time, I could not process that. All I could feel was the tension of waiting for the mask to drop. I watched an American guard walk past our table. He glanced at the untouched food, slowed slightly, then kept going. No sneer, no command, no satisfaction.

That unsettled me more than shouting ever could have. If they were not trying to humiliate us, then why had they fed us this way? Why no rules? Why no enforcement? Why did it seem as though they genuinely did not care whether we were impressed, offended, or afraid?

The possibility crept in quietly, unwelcome, and dangerous. What if this wasn’t theater? What if this was simply how they lived? That idea was harder to bear than cruelty. Because cruelty confirmed what we already believed. Normality did not.

I pushed the thought away. Not yet, I told myself. Don’t believe it yet. Belief was the most dangerous thing a prisoner could give up too soon. I looked down at the hot dog again. The waxed paper had softened completely now, warm and slick beneath my fingers. Steam no longer rose from it. But the smell remained, persistent, inviting, impossible to ignore.

My stomach twisted, not with hunger, but with the effort of restraint. This, I realized, was the true test. Not pain, not violence, but whether we would cling to dignity, even when no one seemed interested in taking it from us.

They told us this was how humiliation began.

And as I sat there, caught between memory and reality, between expectation and evidence, I could not yet tell whether the warning had been right, or whether everything we feared was about to collapse under its own lies.

The moment we expected never came. No shouting. No orders. No laughter at our expense. What came instead was something far more unsettling. Time.

The Americans finished eating before we did, before we ate at all. Trays scraped lightly against tables. Benches creaked as men stood, stretched, and drifted away in loose clusters. Someone tossed a crumpled napkin into a dented metal trash can. It landed with a hollow clang and stayed there. Life moved on. And still no one had touched us.

I realized then that the silence we had feared was not a trap. It was simply the absence of pressure, of spectacle, of control.

One of the guards returned a few minutes later, not to watch us, not to speak. He carried his own food again, unhurried, and this time he sat down at the far end of our table. He did not face us directly. He did not address us at all. He unwrapped his hot dog, folded the wax paper beneath it to catch the grease carefully, almost habitually, and took a bite.

No announcement. No explanation. Just a man eating lunch.

I felt my pulse quicken. This was not what we had prepared for. He chewed slowly, looking out toward the fence as if lost in thought. After a moment, he reached for a paper cup, drank, wiped his mouth with a brown napkin, and continued eating. The napkin was plain, rough, the kind used everywhere I would later learn. Diners, kitchens, work sites. He used it once, then again, then folded it and set it beside his tray instead of throwing it away.

That gesture stayed with me. It was so small, so unremarkable, and yet it told me more about this place than any speech could have.

This was not generosity as performance. This was habit. A way of moving through the world shaped by restraint, practicality, and an unspoken belief that dignity did not need to be rationed. Not even in wartime. Not even toward enemies.

We finished eating. No one hurried us. No one praised us. No one commented.

When I stood to clear my tray, my legs felt unsteady. Not from weakness, but from the effort of recalibrating everything I thought I knew. As I dropped the waxed paper into the trash, it made the same hollow sound as the others. I remember thinking absurdly how ordinary it all felt.

That ordinariness was the shock. Because nothing in our training had prepared us for an enemy who did not need to humiliate us to feel strong. An enemy who understood that real power could afford to be quiet.

No one forced us. And in that absence of force, something inside me shifted just enough to make room for a dangerous, unfamiliar thought.

If this is how they treat prisoners, then who are these people really?

The first bite should have ended it. That was what I believed. One bite, then another. The body would remember how to eat. The moment would pass. We would return to ourselves, to control, to the careful distance we had learned to keep from hope.

Instead, the opposite happened.

The second bite opened something I had sealed away so completely that I had forgotten it existed. The heat of the bread faded, replaced by something else.

Memory rising fast and without permission.

Not images at first, sensations. The sound of a kitchen clock ticking. The faint scrape of a chair across tile. The smell of onions browning slowly, patiently, as if they had all the time in the world.

I stopped chewing. My hands trembled, and I lowered the food back onto the paper, afraid that if I didn’t, I would lose control entirely.

I was no longer in Texas. I was standing in my mother’s kitchen.

It was a small room, narrow. The windows faced the street, and in the morning sunlight, the light would fall across the table in a soft rectangle that moved almost imperceptibly as the hours passed. My mother used to chase that light with her work, setting bowls and cutting boards where it landed best.

On Sundays, before the war, she cooked without hurry. Bread rested on a wooden board covered with a cloth to keep it warm. My father read the newspaper aloud, pausing to comment on articles no one else cared about. My younger brother hovered near the stove, waiting for scraps.

The world then had felt solid, predictable, safe.

The smell I carried now, the meat, the bread, had unlocked that room completely. I could see it. I could hear it. I could almost feel the worn edge of the table beneath my fingers.

I swallowed hard. The table in front of me blurred.

Across from me, Greta made a small sound. Not a sob. Not even a gasp. Just a sharp intake of breath, caught halfway in, as if her body had forgotten how breathing was supposed to work.

I looked up. Her face had changed. Her eyes were fixed on nothing. Her mouth trembled slightly as if she were trying to say something but could not find the language for it.

Then, without warning, tears spilled over, not dramatically, not loudly, but with the quiet inevitability of water breaking through a dam that had held too long.

She brought her hand to her mouth, horrified by herself.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I don’t know.”

No one answered her. No one laughed. No one looked away in embarrassment. The table went still. For a moment, the only sounds were the faint hum of insects and the distant clatter of dishes somewhere beyond the serving line.

An American guard stood up. My body tensed immediately, instinct overriding reason. He did not raise his voice. He did not approach her directly.

He reached instead to a nearby stack and picked up a small bundle of brown paper napkins. He set them down gently on the table, close enough for Greta to reach without standing. Then he stepped back. He did not watch her use them. He did not linger. He turned away as if this were the most ordinary thing in the world.

That was when my throat closed completely. I understood then that Greta was not crying because she was hungry. None of us were. We had eaten. Our stomachs were warm, full even.

She was crying because the food had reminded her of who she had been before the war decided who she was allowed to be. Because for a few seconds, her body had returned to a time when meals meant family, not survival, when eating did not require courage.

I felt it spreading through the table, quiet and contagious. One woman stared down at her hands, blinking

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.