“This Can’t Be Real Food” – German Women POWs Break Down After Their First American Hot Dog. VD

“This Can’t Be Real Food” – German Women POWs Break Down After Their First American Hot Dog

Title: A Fork of Mercy

June 18th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas.

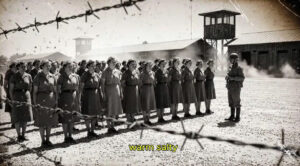

The first thing that struck us when the truck stopped was the smell. It was warm, comforting, and utterly out of place. In a place like this—a POW camp in Texas, surrounded by barbed wire and sun-scorched earth—the last thing we expected was a smell that hinted at home. But there it was, wafting through the air: the unmistakable scent of fresh bread, warm, soft, and inviting, mixed with the rich scent of real butter. It moved toward us, as if it was unsure it belonged in a place like this. The smell slipped through the cracks of the barbed wire, curling its way around the camp as if trying to reach us.

We had been through hell already. Years of war, endless trains, filthy camps, the stench of sweat, fear, and hunger had left their marks on us. So, when we heard the first rattle of the metal cart, carrying food that smelled so… normal, I froze. The sound wasn’t what I expected—there was no clanging of chains, no military noise. It was the sound of someone preparing a meal, something that seemed to belong to another world altogether.

The cart creaked to a stop near the mess hall, and I felt my stomach twist—not from hunger, but from confusion. The smell was so thick, so full of life, that it felt like a betrayal. We were prisoners—enemy women captured in France and shipped across the ocean to Texas. This meal, this smell, it didn’t belong to us. It didn’t belong to a warzone. It didn’t belong to anyone who had known hunger, scarcity, or loss.

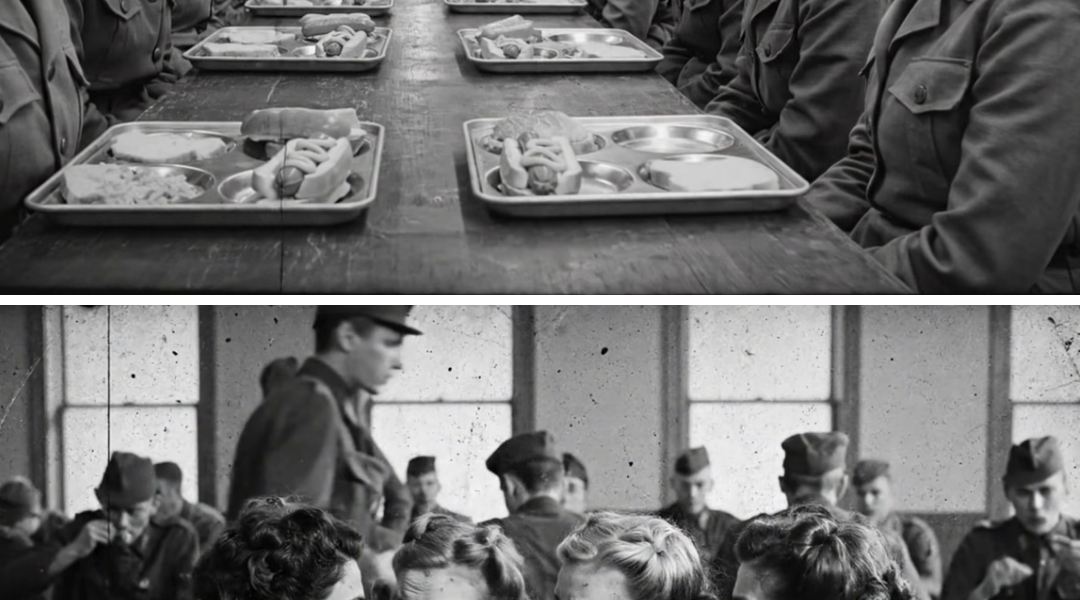

I stepped down last from the truck, my legs weak from the long journey, my body still sore from the months of deprivation. We were led in a line toward the mess hall, where the smell grew stronger, and the sounds inside became clearer. The laughter of American soldiers, the clinking of metal trays, the smell of food that wasn’t just sustenance, but a luxury we had long forgotten. It didn’t make sense.

The doors of the mess hall swung open, and the light inside nearly blinded me. It wasn’t the light of a prison camp, harsh and clinical, but the warm glow of a dining room—something from another world entirely. I stood frozen, unsure of whether I should step forward. Inside, the tables were set as if for a family meal. White napkins, polished silverware, the soft murmur of soldiers talking casually among themselves. There was no urgency, no fear. Just ordinary people having an ordinary meal.

This wasn’t a POW camp. This was something else entirely.

A voice called us forward, and we moved slowly, hesitantly, not sure what to do. The line moved toward the serving counter, where a man in a dusty uniform was placing something onto metal trays. Hot dogs. I couldn’t believe my eyes. In Germany, hot dogs were a distant memory, a luxury we hadn’t seen in years. Here, in the land of our enemies, they were being handed to us like they were nothing. Like they were a part of everyday life.

I stared at the hot dog in front of me, unsure of what to do. It was warm, fresh, perfectly cooked, nestled in a soft, white bun. I wanted to reach for it, but something inside me held me back. I had been taught to distrust anything the enemy offered. I had been taught that America—America that we had been told was cruel and heartless—would starve us, treat us like animals. Yet, here I was, looking at a meal that seemed as far from cruelty as possible.

One of the American soldiers behind the counter noticed my hesitation. He placed the hot dog onto my tray with a practiced motion, barely glancing up at me. His face was ordinary, unremarkable, and yet something about the way he handed me the food made it feel like a gift rather than an obligation. I stepped forward, feeling the weight of the tray in my hands, and sat down at one of the long tables.

My body was hungry—starving, really—but my mind was in turmoil. I had been trained to believe that the enemy was ruthless. That the Americans, in their vast, rich country, were cold-hearted, calculating, and brutal. But none of that seemed to match the scene before me. There were no threats, no demands. No one shouted at us, no one ordered us around. The soldiers ate their meals as if it were just another day, as if they had nothing to prove. And for the first time in years, I felt a strange discomfort wash over me. I didn’t know how to react to this. I didn’t know what to do with kindness.

The women around me sat silently, staring at their meals as I did, unsure of how to proceed. No one moved. The food sat untouched, as if the very act of eating would betray something deeper. The guards were sitting nearby, eating their own meals, laughing casually, as if they weren’t guarding prisoners but simply sharing a meal. The whole situation felt wrong. This couldn’t be real. It was too normal.

One of the women beside me, Lisil, leaned forward and whispered, “We shouldn’t eat it. It’s a trick. It’s all part of the plan.”

I understood her fear. For three years, we had been taught to distrust anything the enemy offered. We had been told that the Americans tortured their prisoners, starved them, and used them for experiments. But here, they were offering us food. They were treating us as though we were guests, as though we were human beings, not enemies. The realization made my stomach churn with discomfort.

I picked up the hot dog slowly, my hands trembling. The bread was soft, yielding beneath my fingers. The mustard bottle beside it was so ordinary, so mundane, it was almost absurd. I raised the hot dog to my mouth, my thoughts swirling with doubt and fear. And then, I bit into it.

The taste hit me instantly. It was salty, savory, warm. It tasted like food—real food. It tasted like something from a world I had almost forgotten. As I chewed, I felt the strangest sensation wash over me—something I hadn’t felt in years. It was relief, mixed with disbelief, and even a little shame. In Germany, we hadn’t eaten like this in so long. We hadn’t tasted meat, real meat, in months. To eat like this—so freely, so without fear—felt like an act of rebellion against everything I had been taught.

Around me, the other women began to eat as well, hesitantly at first, then with more confidence as the minutes passed. They too were breaking down the walls we had built around ourselves—walls of fear, distrust, and anger. But none of us had prepared for the feeling that came with it. The feeling of being fed, of being treated like human beings, not prisoners.

And yet, as I ate, I couldn’t shake the thought that this meal—this simple, ordinary meal—was more than just food. It was a test. A test I wasn’t sure I was ready for. The hot dog in my hand suddenly felt heavy, like a weight I wasn’t sure I could bear. It wasn’t just food. It was the realization that everything I had been taught was wrong. The enemy, the Americans, were not the monsters I had been led to believe they were. They were kind. They were generous. And that thought terrified me more than any weapon.

The meal was simple—hot dogs, bread, mustard—but it was the simplest gestures that began to break us. A soldier passed by, carrying a basket of bread. Without a word, he set it down beside us, as if it were just part of the routine. There was no ceremony, no fanfare. He didn’t even look at us. He just placed the bread on the table and walked away. And in that moment, I realized that what we were witnessing wasn’t kindness born out of pity or mercy. It was routine. It was how they lived.

And that, more than anything, began to break something inside me. Not because I wanted to be broken, but because I realized that the system they had built was stronger than the walls we had constructed in our minds. They were confident enough to be kind. They didn’t need to prove their strength through cruelty. They didn’t need to make us feel small to feel big. They had enough to offer—enough food, enough space, enough kindness—that it didn’t need to be earned.

As I finished my meal, I realized something else—that this moment, this small act of mercy, would stay with me long after the war was over. It wasn’t about the food. It was about what it represented. It was about a country confident enough to offer kindness without expecting anything in return. And in that moment, I saw the true strength of America—not in its military, not in its factories, but in its ability to treat its enemies with dignity.

That night, as I lay on my bunk, the sound of the camp settling around me, I thought about what I had just experienced. The war outside was still raging. Germany was still fighting. But here, in this small, quiet camp, something had changed. I had been treated not as a prisoner, but as a person. And that change, small as it was, meant more to me than anything the war could have ever taken.

The next day, as I returned to my work, I looked around at the other women. We had all been broken in different ways, but in that mess hall, we had been fed in more ways than one. I didn’t know what the future held, but for the first time, I believed it might not be as bleak as I had been taught to expect.

America had fed us—not just with food, but with dignity. And in that moment, I knew that they had already won the war. Not by force, but by choosing kindness.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.