Corn on the Cob: How American Abundance Crushed German Propaganda in a World War II POW Camp. NU

Corn on the Cob: How American Abundance Crushed German Propaganda in a World War II POW Camp

In the muddy fields of a transit camp near Kublans, Germany, in April 1945, the final days of World War II unfolded not with gunfire but over a simple meal. Thirty-four German women, captured as Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht auxiliaries, sat on wooden benches in tattered uniforms, their faces emaciated from months of starvation. They expected cruelty from their American captors—propaganda portrayed the Allies as barbarians. Instead, they were served trays of piping hot food, including bright yellow corn on the cob, grilled and dripping with butter. “Is this pig food?” one of them whispered in horror. But within an hour, laughter echoed through the camp as the women devoured the corn, licking the butter from their fingers and begging for more. This seemingly trivial incident – a bite of corn – challenged everything they believed about their enemies and broke the cultural chasm that the war had created.

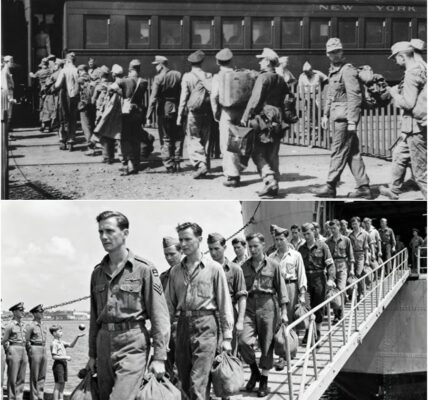

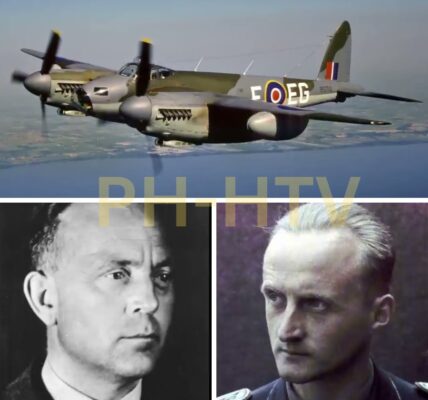

The story begins with the women themselves. Analise Breni, a 23-year-old communications assistant from near Cologne, spent the war directing communications in a concrete bunker. She surrendered in the farmyard, arms raised, after American forces surrounded her position. “I thought they were going to shoot us,” she later recalled. Beside her were Renati Stalberg, an army nurse who treated wounded soldiers without morphine or bandages; Walrod Feifer, a telephone operator from Berlin; and Alfred Latiman, a 19-year-old anti-aircraft gunner from Frankfurt. Mobilized to liberate the men on the front lines, these women believed in the Reich’s promises of victory. In April 1945, as the Western Allies advanced, they faced capture. Staff Sergeant Virgil Tibido, a Cajun from Lafayette, Louisiana, directed their processing. Raised on gumbo and jambalaya, Tibido understood the power of food to unite. “Meals are sacred,” he often said, echoing his mother’s teachings.

The American military’s logistical miracle solidified this moment. By 1945, the U.S. Army operated the largest supply system in history, shipping 800,000 tons of supplies a day across the Atlantic. Trucks like those on the Red Ball Express carried rations—coffee, sugar, flour, powdered eggs, canned meat, and corn—from ports in France to the front. Prisoners of war ate the same food as soldiers, in compliance with the Geneva Conventions, but also for strategic reasons: well-fed prisoners didn’t riot or spread disease. Corporal Emmett Lindfist, a Swedish-American from Minnesota, wrote home: “Today we unloaded crates of corn from Iowa. The Germans looked at them as if we had delivered gold.” Private Lester Simansky, a farm boy from Nebraska, worked in field kitchens, feeding 1,200 men in a few hours. Breakfast: powdered eggs and toast; lunch: meat, potatoes, and bread. The Germans received identical portions.

Corn, an American staple, was alien to Germans. In the US, farmers produced over 3 billion bushels a year by 1945. Sweet corn was grilled at picnics, cooked for dinners, and served at festivals. But in Germany, corn (called “Mais”) was animal feed—cut into silage for pigs and cattle. No self-respecting family ate it. When women saw the grilled cobs glistening with butter, they rejected them. “They’re feeding us animal feed,” muttered Hannal Fikner. Oty Drexler, an administrative official from Munich, pushed away her tray: “They think we’re animals.” The cultural divide was clear. Germans had grown corn for centuries, but never for humans. Americans saw it as a comfort food.

Private Delbert Martinelli, an Italian-American from Brooklyn, New York, smiled as he served it. “Corn straight from the grill. You’ll love it.” The women hesitated, their pride wounded. But hunger prevailed. Analise Breni, watching the Americans feast on the same meal, lifted her cob. One bite exploded with sweetness—delicate kernels, smoked charcoal, creamy butter. “This isn’t pig food,” she gasped. Walrod tried next, then Renati, Hannal, and even Oty. Laughter erupted as they devoured their second helpings. “My God,” Walrod exclaimed. The camp was transformed. Meals became moments of connection. The women helped in the kitchen, organizing trays and cleaning. Renati, with her nursing prowess, streamlined distribution. Mechild Weedderman, the barracks supervisor, enforced order. Walrod discovered Private Woodro Pettigrew, a black soldier from Georgia, playing the harmonica. Nightly concerts followed, where blues melodies provided a unifying element.

For the Americans, it was routine. Tibido, from the Louisiana swamps, treated the prisoners humanely, sharing water and blankets. Lindfist, from the Minnesota lakes, noticed the change: “They stopped treating us like enemies. Maybe it’s the corn.” Pettigrew, homesick, played music that reminded everyone of home. Simansky, from the Nebraska cornfields, taught barbecue techniques. These men, from diverse American backgrounds—Southern Cajuns, Midwestern farmers, urban Italians—embodied American abundance. Their well-fed, healthy appearance contrasted with the hunger of the women, refuting Nazi propaganda about American “mutts.”

The war ended on May 8, 1945, but the women remained in the camps for several more weeks. Freed, they returned to a devastated Germany—cities in ruins, families scattered. Yet they carried with them memories: warm meals, kindness, and corn. Analise told her mother, “It was sweet, nothing like pig feed.” The families were initially skeptical, but stories quickly spread. Then came American aid—food deliveries allowed infrastructure to be rebuilt. In the 1950s, sweet corn became part of the German diet, grown for human consumption and sold in supermarkets.

In 1987, the German oral history project “Stimmen der Generation” interviewed survivors. Analise Breni Sauer, 75, laughed: “We thought they were mocking us. Then we tried it. At that moment, I knew we were being lied to.” The corn incident, small in the context of the war, changed thinking. It showed the enemies as human beings and the propaganda as false. Food, not bombs, helped to calm the conflict.

American soldiers like Tibido, Simansky, and Pettigrew returned home—Louisiana stew, Nebraska fields, Georgia melodies—carrying their own lessons. The camp near Kublans has become a mere footnote, but its message remains relevant: abundance and kindness can heal divisions. In a world of conflict, a shared meal reminds us of our shared humanity.

Note: Some content was created with the help of AI (AI & ChatGPT) and then creatively edited by the author to better reflect the context and historical illustrations. I wish you a fascinating journey of discovery!