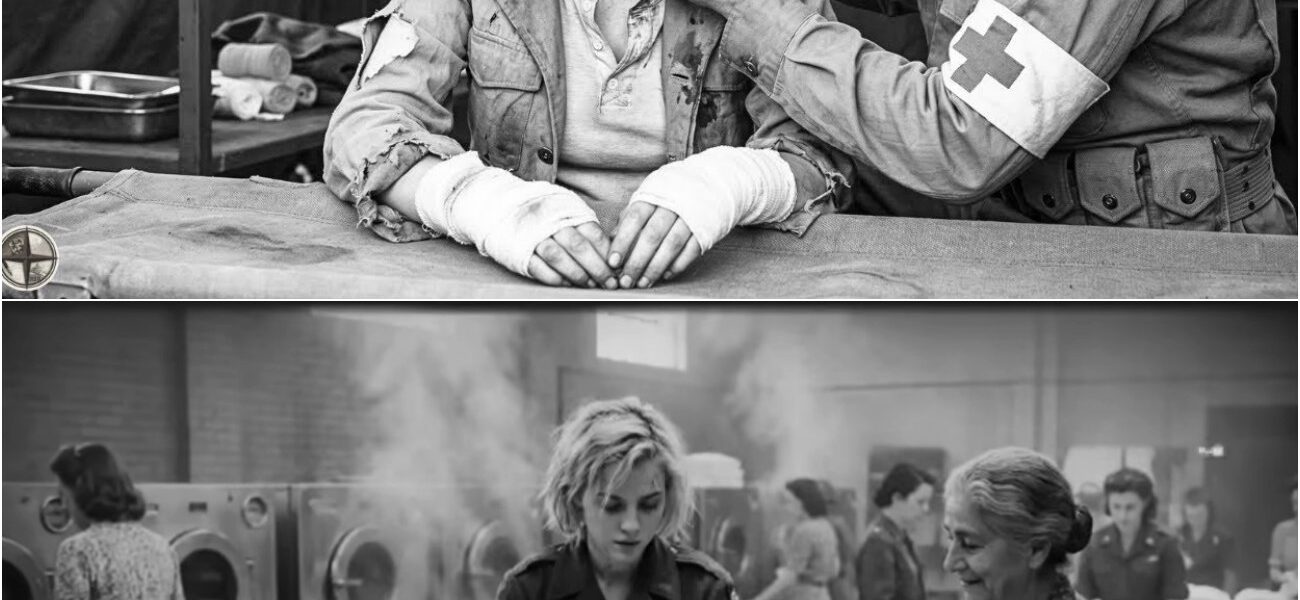

“My skin hurt” — A German prisoner of war is in shock after U.S. Army medics saved her life and prevented her from losing both hands. NU

“My skin hurt” — A German prisoner of war is in shock after U.S. Army medics saved her life and prevented her from losing both hands

March 1945, Fort Sam, Houston, Texas. The American medic stared at the young woman’s hands and murmured four words that would haunt him for decades: “How are you alive?” Her fingers were black, not bruised. Necrotic, black tissue that should have killed her weeks earlier from septicemia. She had crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a freezing cargo hold with forty other women, and no one had given her even the slightest bandage.

Now, at 17, she sat in the enemy hospital, waiting for the Americans to decide whether she deserved to keep her hands or her life. She had been told that the Americans tortured prisoners. The propaganda was clear: capture meant death. But what would happen in the next 40 minutes would shatter all her beliefs about the enemy, about mercy, about which side was telling the truth.

This is the story of a German nurse whose hands were left to rot and the small-town Oklahoma doctor who had every reason to let her die, but didn’t. His act changed their lives forever and proved that even in the darkest war in history, a single choice could defeat an empire of hatred. If you’ve never heard a World War II story like this, subscribe now, because what you’re about to see will restore your faith in humanity.

And most importantly, watch until the very end, because the last words she whispered 64 years later will break your heart. Let’s go back to that Texas morning when everything she thought she knew about America was about to crumble. The telegram arrived at Fort Sam Houston on a Tuesday morning, under a low, gray sky over Texas.

The message read: “Arrival of German prisoners at 8:00 a.m. Military auxiliaries captured Belgium during the winter offensive. Apply standard detention protocols.” Colonel Warren Fischer, the base commander, read the message twice, then handed it to his agitator. “Prepare the men’s barracks. Notify the military police. Standard admission procedures.” No one expected the presence of women.

The trucks, covered with tarpaulins, passed through the gate at 8:15 a.m., their diesel engines coughing in the damp spring air. The guards at the checkpoint signaled them to proceed toward the detention camp, surrounded by barbed wire and wooden barracks built for captured Luftwaffe aircrews or branded infantrymen—the kind of prisoners America had been dealing with since 1943.

When the situation changed and thousands of German soldiers began to surrender in North Africa, the tarpaulins on the trucks opened, revealing young girls. Forty women in gray wool uniforms climbed down from the flatbeds, moving slowly, as if they had forgotten how to walk. Some looked sixteen, others twenty-five.

They all had the same expression. Their eyes fixed on the Texas soil, their faces etched with exhaustion, their bodies carrying a burden heavier than their small canvas bags. Sergeant Roy Kemp, notepad in hand, stared at them for a good ten seconds before remembering his mission. He began calling out names from a list typed by a Belgian who had transcribed everything phonetically.

Lisa Voss, Margarit Drestler, Illy Ilsa Drestler, stepped forward when she heard a name similar to her own. She was 17 years old, with short blond hair cut like a boy’s, and her hands were wrapped in gauze that had once been white but was now stained brown. She had been bound like this for three weeks.

The Atlantic crossing had been a nightmare, an ordeal in the darkness and ice. The hold of a Liberty ship, designed to carry tanks and ammunition, not human beings, was overcrowded. Forty women were crammed into a space of six square meters. Metal walls dripped with freezing condensation from the February storms. Temperatures were so low that their breath turned to frost on their lips.

No blankets, no heating. The ship’s captain had been informed that these were enemy prisoners, not priority passengers. The Geneva Convention stipulated that they were entitled to minimal treatment. Minimal meant being alive upon arrival. They huddled together for warmth, taking turns holding each other. The women on the outside were freezing while those in the center struggled to stay warm.

Elsa had given up her place in the center by the second night to an older woman who was coughing up blood. By the third night, Elsa couldn’t feel her fingers. By the fifth, they had turned purple. By the tenth, she had stopped looking at them. When the ship finally docked in Virginia, fourteen days later due to storms, the Navy medic who opened the hold vomited overboard before calling for help.

Two women did not survive the sinking. Their bodies were listed as victims of the transport and buried in a military cemetery near Norfolk, under headstones marked “unknown German national.” Elsa, however, barely survived. Now she stood in the bright Texas sun, so intense it almost weighed her down, waiting to find out what would happen. The base hospital was a low, white building topped with a red cross.

Protection against air raids that would never reach this region, thousands of kilometers from any front line. Inside, it smelled of disinfectant, floor wax, and a clean scent Elsa hadn’t smelled in months. The fluorescent lights hummed on the ceiling, bright and steady. No flickering candles or dim bulbs in the basement. Everything shone.

Captain Aldrich Peton ran the medical admissions department with weary efficiency. Fifty-three years old, with graying hair thinning at the temples, this Boston doctor had enlisted in 1942, expecting to serve overseas, but had been assigned to the P administration in Texas. He had examined hundreds of German prisoners, submarine crews rescued from the Atlantic, Marines from the African Corps captured in Tunisia, and Luftwaffe pilots shot down over France.

Most arrived in fairly good health, thin, perhaps exhausted, certainly, but functional. These women were different. Malnutrition, he noted on his notepad as the first one stepped forward. Probable vitamin deficiency. To be sent to the kitchen for extra rations. Cold damage, he wrote for the next, slight frostbite on her extremities.

Standard treatment protocol. Ilsa Drestler then sat down in the examination chair. Peon gestured to her hands. “Let’s see.” She extended them slowly, like a witness on the stand. He began to remove the gauze. It was stuck to her skin. Elsa made a sound, not a cry, not a scream, just a small, muffled noise, like air escaping through a crack. The tissues came away in pieces.

Peton froze. For a good three seconds, he stood there, his eyes fixed on what lay below. Then he turned towards the door and called out: “Pruit, I need you right away!” Nurse Puit was restocking the supply cupboards in the next room, counting the sulfur packets and rolling new bandages into neat white cylinders.

He was 22 years old, tall and thin, with perpetually messy black hair and hands of surgical precision. His Oklahoma accent was still quite noticeable despite two years spent in Texas. A medic, he had dreamed of being a soldier, but had been reassigned because his left ear constantly tinnitus following a childhood fever. An injury that had disqualified him from combat.

He had spent six months feeling cowardly before the wounded arrived from Europe. Then, he felt nothing but intense activity. He entered the examination room and saw Ilsa’s hand. “My God,” he murmured. Frostbite had reached third-degree necrosis on three fingers of her left hand.

Second-degree burns, because that’s what the extreme cold caused. The burn was so severe it covered both her palms. In places, the tissue was necrotic, the dead flesh turning purple, gray, and black where cells had frozen and never regenerated. An infection had set in. Red lines radiated from the wounds to her wrists, like rivers of poison flowing toward her heart. She should have screamed.

Iltsa Dressler, unperturbed, remained seated in the examination chair, her eyes fixed on a point above Captain Peton’s shoulder, breathing through her nose in small, regular breaths. The pain was so constant it had become a habit, a background noise. She had learned to live with it, like soldiers learn to sleep despite artillery fire.

The EMTT team had already treated war wounded: soldiers repatriated from Europe with shrapnel wounds, bullet impacts, and tank burns. But those men had received immediate medical care, field hospitals, morphine, and evacuation within hours. This young girl, however, had been left to fend for herself for weeks, even months. The infection alone could have been fatal.

Sepsis didn’t care about the uniform. “How long has she been in this condition?” the paramedic asked. Peton consulted the shipping manifest. “The ship left Belgium on February 14th. It arrived in Virginia on March 9th. She remained there for six days awaiting treatment. That brings us, according to his calculations, to at least five weeks since the initial injury. Perhaps longer if it occurred before boarding.”

Five weeks of necrosis poisoning her blood. Five weeks of spreading infection. Five weeks of suffering that should have plunged her into shock. The paradox was obscene. America had spent billions of dollars on medical technology to save its own soldiers: sulfur-based drugs to fight infection, blood plasma to prevent shock, evacuation systems capable of transporting the wounded from the battlefield to the operating room in less than twelve hours.

The U.S. Army Medical Corps had reduced the death rate from infected wounds to less than 4%, compared to 30% during World War I. Penicellin was already being tested in military hospitals, with seemingly miraculous results, and this young girl had been left to die slowly in the hold of a ship because no one deemed her worthy of the price of a blanket.

“We need to debride immediately,” Peton said. “Remove all the necrotic tissue before the infection reaches the bone. If it’s already reached the bone…” He didn’t finish his sentence. They both knew amputation was possible. Maybe the whole hand. Maybe his life if they arrived too late. Elsa watched them talk. She didn’t understand a word of English, but she grasped the medical tone.

Before the war, she was a nursing student in Hamburg. Two years of training before the bombs started falling and the university became a treatment center for the wounded. She knew what the doctors were like. They discussed the possibility of saving a patient. She had expected that, not the discussion, not the abandonment.

In the Belgian detention center, a guard had looked at her hands and laughed. “Americans don’t waste medicine on German dogs,” he had said in broken German. “They’ll let you rot.” She had believed him. Why wouldn’t she? The propaganda was clear. The Americans were cruel, greedy, obsessed with revenge. They executed prisoners.

They tortured captured soldiers. They had no honor, no pity, no humanity. So, when the ship locked her in darkness and cold for three weeks, it was like confirmation. When her fingers turned black and no one came to her aid, it was like standard procedure. When the pain became so intense that she could no longer sleep or think, that she could only exist in a present burning with suffering, she accepted it as the price to pay for having been on the losing side.

These American doctors were now talking about saving his hand. It was absurd. Peton was already moving on to the next patient. Forty women to care for, limited time, military efficiency. “This is your case. Clean it thoroughly. Debride all the necrotic tissue. Absolutely all of it. Leave nothing that could worsen the situation. Sulfur powder, apply generously.”

Fresh dressings changed twice a day. Keep her here for observation. Watch for fever, increased swelling, and redness spreading beyond the wrist. Any signs of sepsis? Call me immediately. Understood? Yes, sir. Does she speak English? I don’t think so, sir. Peton looked at Elsa for a moment. Her face was blank, vacant, the expression of someone who had given up on the world having any meaning.

Okay, do your best. She needs to understand that we’re trying to help her, not hurt her. I suppose the next hour is going to be pure torture anyway, he said as he left. The room suddenly seemed larger, quieter. The paramedic gathered his equipment: surgical scissors, tweezers, antiseptic solution that would burn like fire on an open wound.

Sterile, white gauze rolls. Sulfur powder in small paper packets. A miracle drug developed in 1935. Reduced mortality from infections by 60 percent. The kind of drug that could save lives if it weren’t too late. He approached Ilsa slowly, like one approaches a frightened animal. She looked at him with an expectant, cruelty-inducing gaze and had already decided not to resist, as if she had learned that fighting only made things worse, as if she had learned to endure.

EMTT had seen that expression before on the faces of soldiers wounded time and again, who had lost all hope and were clinging on only to a stubborn struggle for survival. It angered him, not at her, but at the system that had left a 17-year-old girl to suffer like that for five weeks without any help. He grabbed a stool and sat down at her level.

“Very well,” he said softly, knowing she didn’t understand his words, but hoping his tone would be enough. “This is going to hurt. I’m sorry, but we’ll fix this. You’ll keep your fingers. I promise.” She stared at him, uncomprehending. He took the scissors and reached for her left hand.

She flinched, a tremor running through her entire body, but she didn’t break free. That’s when he understood. She thought it was the amputation. Emmett saw the fear cross her face. The certainty that he was going to cut off her fingers right there, right then and there, without anesthesia or warning, just to eliminate an enemy—efficient American cruelty.

“No, no,” he said quickly, raising both hands, the scissors pointing in the opposite direction. “I’m not cutting, I’m just cutting the bandages. The old bandages, you see?” He mimed unwrapping them, his hands circling invisible rolls. Then he pointed to the roll of clean white bandages on the tray beside him. “Olaf, new, help me, medicine. Do you understand?” She didn’t understand, but she stopped struggling.

He began to cut away the outer layers of stained gauze. The fabric had stiffened where the blood and fluids had dried. Beneath, the next layer was damp, stuck to the skin by a bodily ooze that gave off a sickly sweet, putrid odor of infection. He had smelled it before on soldiers who had spent days in muddy trenches, their wounds untreated.

The gang green had a distinctive smell. It wasn’t quite that far along yet, but it was close. He worked slowly, cutting away sections, peeling back the layers clinging to the necrotic tissue. Each detached piece took away shreds of skin. Elsa’s shoulders began to tremble. Fine tremors that ran up her arms to her mangled hands. “Not fear, just pain.”

The pain was so intense that her body couldn’t stay still. “You’re doing really well,” Emmett said softly, his voice calm and low. “You’re braver than most of the soldiers I’ve treated. Hang in there a little longer.” The words meant nothing to her, but the tone did. She focused on his voice as if it were an anchor, something to cling to while her nervous system screamed.

When the last bandage was removed, he filled a steel basin with warm water and an iodine antiseptic solution that gave it an amber tint. He gently dipped his hands into it. She gasped. A sudden inhale, the antiseptic hit her full force, exposing her nerve endings like liquid fire. Then the tears flowed, silent, steady, tracing clear lines across the dust that covered her face.

She was crying without sobbing, without making a sound, just tears flowing from her eyes that had held them back for too long. The paramedic soaked his hands for three minutes, giving the antiseptic time to work and kill the surface bacteria. Then he began the debridement. This was the step that required precision. The necrotic tissue had to be completely removed, otherwise it would continue to contaminate the surrounding living tissue.

But the incisions mustn’t be too deep. The healthy tissues trying to regenerate mustn’t be damaged. It was delicate work, more an art than a science, acquired through practice on hundreds of wounds. He used tweezers to lift the necrotic skin, surgical scissors to trim the edges. The dead tissue was grayish-black, firm, and completely separated from the underlying living flesh.

On her left index finger, the lesions were deep, reaching the dermis and hypodermis. On her palms, the skin was split in several places, hardened fissures, never properly cleaned, now filled with dried blood and infection. Ilsa trembled even more violently. Her breathing was ragged, through clenched teeth.

Tears streamed down her knees, staining the gray wool of her uniform. But she didn’t turn away. The orderly continued speaking. “Everything will be all right. These wounds will heal well if we keep them clean. There’s good tissue under all these lesions. You see?” He pointed to a spot on her palm where healthy, pink skin was visible beneath the gray.

That’s already healing. Your body is doing the work. We’re just helping it. She didn’t understand his words, but she looked where he was pointing and saw the pink. A glimmer crossed her eyes. Perhaps hope, perhaps simply confusion from exhaustion. The procedure lasted 43 minutes in total.

When he had finished unbridling, the water in the pool had turned dark, thick with blood and necrotic tissue. His hands were in worse condition than when he started. Raw and exposed, they bled where he had removed the necrotic flesh, but they were clean. Truly clean for the first time in five weeks. He dried them carefully with sterile compresses, gently dabbing around the wounds.

He then opened the packets of sulfur powder, six in total—more than the standard protocol recommended, but he wanted complete coverage. The white powder fell like snow onto the raw flesh, coating every exposed surface. Military medical studies had shown that sulfur-based medications reduced infection rates by 64% when applied within 72 hours of injury.

Applied five weeks late, the bandage had lost about 30% of its effectiveness, but it was still better than nothing. That 30% could mean the difference between keeping his fingers and losing them. He began applying new bandages, starting at the fingertips of his left hand, moving down each finger, then covering the palm, around the wrist, and tightening everything carefully: tight enough to protect, but not so tight as to restrict blood flow.

Then the right hand, less damaged, but still seriously injured. The same methodical procedure. Once finished, both hands were wrapped in immaculate white gauze that seemed to gleam under the fluorescent lights. He held them delicately, checking his work, making sure the bandages would hold. “There,” he said.

“This is better, isn’t it?” Elsa looked at his hands as if she were seeing them for the first time. Then she looked at him, then back at her hands. Her lips moved, forming words in German he didn’t understand. “Woram! Hilsttomir, why are you helping me?” The confusion in his voice was palpable. The disbelief, the absurd question—she’d expected it.

Where enemies were enemies, where pity was merely propaganda, where Americans were monsters who abused German women for pleasure. Emmett smiled. “Everything will be alright.” His expression changed. The glass wall cracked slightly, just enough to let in an impossible thought. What if they’d lied to us all?

For the next twelve days, Ilsa returned to the medical ward every morning at 8 a.m. The routine became familiar, almost reassuring in its predictability. A member of parliament escorted her out of the women’s detention area; the barbed wire seemed decorative compared to what she had seen in Europe, watchtowers where men read the newspaper and drank coffee as if it were just a boring mission.

She would cross the parade ground in the morning light. The Texas sun was already scorching in March; the air tasted of dust and smelled of green, which she would later learn was mosquitoes. The emergency response team would be waiting for her in the same examination room. The equipment was already laid out on the metal table: basin, antiseptic, fresh compresses, sulfur powder, surgical scissors that caught the light.

She always sat in the same chair by the window, holding out her hands without being asked. He carefully removed the old bandages, checking for signs of the infection worsening or improving, examining each finger for any changes in color, temperature, or swelling. The first three days were critical. It was usually during this time that sepsis, if present, developed.

A case of septicemia that could have been fatal within 72 hours once vital organs were affected. But by the fourth day, the redness radiating down her wrists had faded. The swelling had decreased. The tissues beneath the damaged layers were regaining their pink color. New skin cells were dividing, regenerating, doing what healthy human bodies do when finally given the chance.

“Good,” Emmett said on the fifth morning. Genuine relief shone in his voice. “Really good. The infections are clearing up, your recovery is faster than expected.” Ilsa watched him work. He was young, maybe five years older than her, though the war aged everyone. His hands moved with surgical precision, without roughness or haste.

He touched her damaged fingers as if they mattered, as if she mattered. It was unsettling. In Germany, she’d been told that Americans were barbarians. Propaganda posters showed Uncle Sam with bloodied hands, standing over piles of dead children. Radio broadcasts described torture camps where German forced laborers were starved and beaten.

Her instructor had told her: “If you are captured, do not expect any mercy. They hate us. They will make you suffer.” But this man spent 30 minutes every morning cleaning her wounds with remarkable gentleness and precision, speaking to her in a low voice, even if she did not understand, and smiling at each step forward in her healing.

On the seventh day, she tried to communicate. She showed him her hands, then his, then placed her palm on his chest. “Danker,” she said. “Thank you.” He understood. “You’re welcome.” She frowned, frustrated by the language barrier. Then she tried again in hesitant, cautious English that surprised them both.

“You’re kind, I don’t understand. Why?” Emmett blinked. “Do you speak English?” She brought her thumb and forefinger together. “Small school before the war. Not good, but a little.” He smiled. “Your English is better than my German, which has absolutely no words.” She almost smiled. Her expression was hesitant, fragile, as if she had forgotten how to do it properly.

Then she spoke of what had haunted her since that first treatment. “In Germany, they tell us that Americans are cruel as animals. They say that if we capture them, they’ll hurt us. They’ll torture us, they’ll kill us, maybe worse.” She paused, carefully choosing her words from her limited vocabulary. “I think that when I come here, you’ll let me die with my hands.”

Punishment for being German, and yet you help. You use medication. You’re careful. I don’t understand why. Emmett stopped bandaging his right hand. The question hung between them, honest, direct, cutting through all the propaganda and political noise to get to the heart of the matter. He asked himself similar questions.

Late at night, in his bunk at the barracks, he wondered why he was so interested in the hands of a mere German woman. While German soldiers had killed thousands of American boys. While German bombs had razed entire cities, while the full horror of the concentration camps was only just beginning to reach American newspapers: photos of skeletal prisoners, mass graves, atrocities so enormous they defied comprehension.

We couldn’t ignore it simply because a 17-year-old had frostbite. But we also couldn’t ignore the frostbite itself, because it required treatment. That’s the role of first responders. We help those in need, regardless of the uniform they wore or which side they fought on. Pain is pain. Infection is infection.

You treat the patient in front of you. Elsa remained silent for a long moment, thinking. Then she thought, “That’s a good answer. Perhaps that’s why America will win. Not just because it has more guns, more planes, more of everything. Because it still sees people as human beings.” The paradox was striking. Two nations had spent years conditioning their populations to hate each other, to dehumanize the enemy, to believe that the other side was fundamentally evil.

Millions of dollars poured into propaganda aimed at normalizing murder, making surrender unthinkable, and pity impossible. And here, in a Texas hospital room, forty minutes of attentive care had shattered all those illusions. The nurse finished bandaging her hand and stitched the wounds. There, she could go on living. They had to be kept dry.

Don’t use your fingers just yet. The healing tissue is fragile, she agreed. Then, in English tinged with a German accent, it became clearer and clearer every day. I’ll be back tomorrow. At the same time. At the same time, he confirmed. She got up to leave, then stopped at the door. EMTT. He looked up. It was the first time she had said his name.

Thank you for seeing me as a person, not an enemy. You were never my enemy, Ilsa. Just a patient who needed help. After he left, the nurse remained alone in the examination room and thought about that word, “enemy.” How easy it was to apply it to millions of strangers across the ocean! How impossible it became after spending twelve mornings tending to one person’s wounds and watching her hands heal.

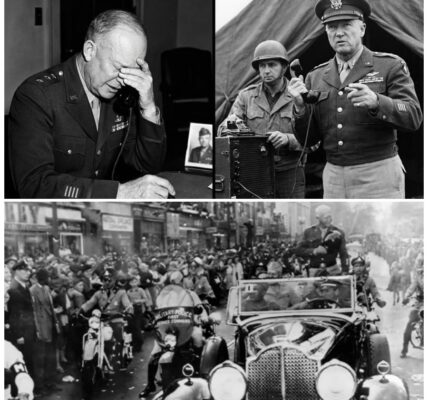

The news reached the radio on May 8, 1945. A Tuesday morning like any other, until everything changed. Germany had surrendered, unconditionally, completely. The regime had collapsed. Hitler was dead. Berlin had fallen. The war in Europe was over. Ilsa was working in the base’s laundry when the announcement crackled over the loudspeakers mounted on the walls.

She had been assigned there after Captain Peetton gave her permission to discontinue her daily medical treatments. Her hands had healed enough for light work; the scars, still pink, were functional. The work was repetitive: washing, drying, folding endless mountains of sheets, towels, and uniforms, the hot steam rising from the industrial machines, the acrid smell of soap and bleach.

Her hands still ached at the end of each shift. Her tendons still bore the marks of her injuries, but they worked. All ten of her fingers were fully functional. The EMTT had kept its promise. The American women working in the laundry stopped dead in their tracks as soon as the broadcast began. Someone turned up the volume. The commentator’s voice filled the building, announcing victory, the triumph of the Allies, the beginning of peace.

Outside, the base was in turmoil. Soldiers were shouting, trucks were honking, and shots were being fired into the air until an officer ordered them to stop. Inside the laundry room, the German women continued folding clothes. A heavy, tense silence hung between them. Ilsa, standing at her table, her hands mechanically performing memorized gestures, was thinking about Hamburg.

The streets she had walked as a child were now nothing but ruins, according to the news that reached her. The whereabouts of her mother and sister were unknown. All communication with Germany had been impossible for months. They could be alive. They could be dead. She had no way of knowing. She thought of her father, killed in 1943 when a bomb struck his school during class time.

Twenty-three students perished with him. She was furious. Furious at the Allies for dropping the bomb. Furious at the regime for starting a war that had sent bombers into German cities. Furious at the universe for its cruelty, its randomness, and its unforgivability. Now the regime had fallen. Its leaders were dead or captured. The great ideological struggle that had consumed millions of lives had been reduced to ashes, mass graves, and cities razed to the ground.

And there she was, alive in Texas, her hands healed, folding U.S. Army bedsheets. Consuel Agira, the supervisor, found her during her lunch break. Canuelo was 56, her iron-gray hair pulled back in a tight bun, her hands rough from decades of work. She had lost a nephew in Normandy and a son-in-law in the Ardennes. She had every reason to hate the women in gray uniforms who worked under her.

Instead, she brought Elsa a glass of cool water. “Are you all right, Miha?” Consuel asked gently. Elsa drank the water. Her English had improved considerably after two months of daily practice. “I don’t know what I am. The war is over. Germany is destroyed. I don’t know if my family is still alive. I don’t know what will happen to us now. They’ll send you home eventually.”

Repatriation, as they call it. It’s a long process, there’s a lot of paperwork, but you’ll go back. Go back to what? Ilsa’s voice was monotonous. There’s nothing. The cities are in ruins. The economy is destroyed. Millions of people are dead. And we’re the ones who lost. The ones who were wrong. Consuel was silent for a moment. So the war doesn’t last forever. Nothing lasts. You’re young.

You will rebuild. We always rebuild. That evening, while Troutg Garing was holding a discreet meeting in the barracks common room, Voltroud, the oldest of them, was 32. A signals officer, she had been captured in France. Her piercing gaze and distrust of everything were familiar to him. For two months, she had warned the younger men about supposed American benevolence, insisting that it was propaganda designed to subjugate them.

But even Walroud’s cynicism had its limits. “We survived,” she told the group of 37 women. Three of them had been transferred to other facilities for various administrative reasons. “After everything that’s happened, we’re still alive. They’ll decide our fate: send us home, interrogate us. Whatever the administration decides, we’re alive. Never forget that.”

Elsa also remembered something else. She remembered Emmett spending 43 minutes meticulously cleaning her hand. She remembered Consuelo bringing her fresh water on hot summer days when the laundry detergent temperature exceeded 38°C. She remembered the MP who had accompanied her to her doctor’s appointment and who had learned to say “Guten Morgan,” even though he pronounced it very badly.

Small acts of kindness from those whom the war had allowed to see as less than human, she who had made a different choice. Perhaps this was how one rebuilt a destroyed world. One small choice at a time. The decision to see people as human beings and not as enemies. That night, lying in her bunk, she stared at her hands in the dim light. The scars were visible, pink lines on her palms.

Slightly darker patches marked three fingers, where the frostbite had been deepest. They would eventually whiten, but would never completely disappear. Indelible marks, witnesses to what she had endured. Her hands had been condemned to die in the icy hold of a cargo ship. Now, they were alive, functional, healing. Because an American doctor had chosen to dedicate 43 minutes to treating an enemy like a patient.

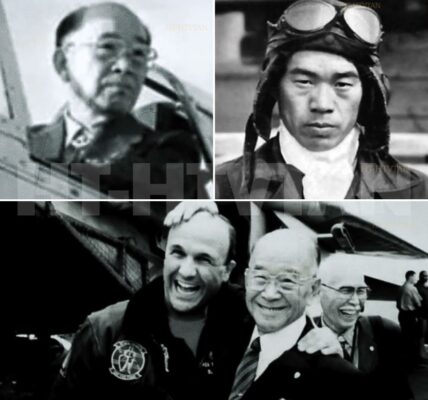

The universe was brutal, random, and often unforgiving. But sometimes, extremely rarely, almost impossible, it held moments of grace that defied all logic. Two weeks later, the EMTT team received transfer orders. The Pacific War was still raging. Japan continued fighting despite Germany’s collapse. Personnel were redeployed. Doctors were sent as reinforcements to prepare for the imminent invasion of Japan.

He was on his way to California, to a field hospital in San Diego, where staff were being trained in anticipation of the massive influx of wounded everyone expected. He caught a glimpse of Ilsa one last time by chance near the base mess hall. She was carrying a crate of supplies. Her hands were bare. No bandages, just scars. She set the crate down when she saw him. “You’re leaving.” Without asking any questions. Somehow, she knew.

Yes, new orders. California. They need paramedics for… well, for what’s going to happen next in the Pacific. She held out her right hand, the one that had been most injured. The one he thought would have to be amputated. Thank you, paramedic, for my hands. For showing me that not all Americans are what they pretend to be.

He shook her hand carefully, aware of the healed wound, the rough scars beneath his palm. His grip was firm. “Good luck, Elsa. I hope you come home safe and sound. I hope you find your family. Good luck to you too. I hope you continue to help many more people.” They stood there for a moment. Two people whose lives had briefly intersected in the chaos of war, who had taught each other a lesson in humanity that no amount of propaganda could erase. Then he left.

She picked up her box and continued working. The Texas sun beat down fiercely, indifferently and eternally. Ilsa Drestler was repatriated to Germany in November 1945. The process lasted six months: the administrative formalities, the security checks, the interviews with intelligence agents who questioned her meticulously about what she had seen, what she knew, and the role she had played.

She was 17 years old, clearly not a war criminal, guilty of nothing more than being a nurse in an inappropriate uniform at the wrong time. She was exonerated without incident. The ship that brought her back across the Atlantic was heated and provided blankets, hot meals served twice a day, and a competent medical team looking after the passengers. The crossing lasted 11 days, and no one’s hands turned black from the cold.

The ship docked in Hamburg on a gray morning in late November. Elsa stepped down the gangplank and discovered a city she didn’t recognize. The destruction was total. Entire neighborhoods reduced to ruins. Not just damaged, but destroyed, vanished. The streets she had walked as a child were now nothing more than paths cleared through the rubble.

Buildings that had stood for two centuries now existed only in memories. People lived in cellars and basements, scavenging for food and burning their furniture for warmth. The British occupation forces maintained order with military efficiency. But the traumatized and shocked population struggled to comprehend what had happened. Ilsa found her mother alive in a village 30 kilometers from the city.

The reunion took place in a small room with cracked windows, barely heated by a wood-burning stove. Her mother had aged twenty years in three, but she was breathing, she was surviving. “Lau is in England,” her mother explained. “She married a British soldier and now lives in Manchester; she’s pregnant with her first child.” The news seemed unreal.

Her younger sister, who was fifteen the last time Ilsa saw her, was married to a former enemy, carrying a mixed-race child, and living in the country that had reduced their town to ruins. The world had shifted and kept turning. Ilsa resumed her nursing studies in 1946. It took her three years to graduate amidst the chaos of postwar Germany, studying in makeshift classrooms with secondhand textbooks, limited supplies, and constant shortages. But she did it.

She spent the next 42 years working in hospitals across Germany, first in Hamburg, then Munich, and finally Berlin after reunification, caring for patients with the same attention and dedication that Emmett Puit had shown her. She married a teacher named Friedrich Vber in 1952. They had three children: two daughters and a son.

She raised them to respect peace, understanding, and the importance of seeing beyond labels, of perceiving the human being. She told them the story of the American doctor who saved her hands when he had every reason not to, who chose kindness over propaganda that demanded cruelty. She lived long enough to see Germany reunified. She witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Tears streamed down her face as people danced in streets divided for decades. She watched her grandchildren grow up in a peaceful Europe, a peace that seemed impossible during those dark years when everything burned. She lived a beautiful life, a full life, a lucky life, all things considered. And sometimes, on summer days, when the heat shimmered on the vast, endless sky, she would look at her hands, now old, marked by age, by faint scars on her palms that had never truly faded.

And she would remember Texas, the dust, the impossible sky, the young doctor who treated her like a human being when the world considered her an enemy. She died in 2009 at the age of 81, surrounded by her children and grandchildren, in a Germany that had rebuilt itself, a country that the 17-year-old girl she was could never have imagined.

His last words, whispered in English with a lingering German accent after 64 years, were: “Thank you, EMTT. I was fine.” Emmett Puit worked in veterans’ hospitals for 33 years after the war. He was never deployed to the Pacific. Japan surrendered three months after his arrival in California. The atomic bombs ended the war before the planned invasion.

Instead, he cared for thousands of patients returning from both theaters of operation, soldiers broken by combat, their bodies and minds bruised by the horrors they had witnessed and committed. He saved some, lost others, and did his best for all. In 1947, he married a nurse named Dorothy Chen, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, who worked at the Naval Hospital in San Diego.

They had two sons, both of whom became doctors, thus perpetuating the family tradition of caregiving. The ringing in his left ear never stopped. This persistent memory of the childhood fever that had kept him away from the fighting had become almost familiar. A background noise he had learned to live with. He sometimes thought of Elsa over the years.

He wondered if she had returned. He hoped she had. He hoped her hands were completely healed, that she had found some semblance of peace on a devastated continent, struggling to rebuild itself. He had tried to find her once before, in 1978, when he was considering retirement. He had written to the Red Cross, contacted military archives, combed through repatriation files. But the trail had gone cold.

Too much time had passed. Too many files lost or destroyed. The bureaucracy of two countries, decades of separation, the vastness of the world. He never knew for sure what had happened to him. But sometimes, he treated a patient suffering from terrible injuries: burns, frostbite, wounds that should have been fatal, but which, against all odds, were not.

And he worked with the same care and attention he had learned in Texas. He thought of her, of that moment when she had extended her healed hand to him, when she had thanked him in impeccable English, when two people from opposing sides in the worst war in history had found a moment of shared humanity. He died in 1996 at the age of 73.

A heart attack in his garden, one Sunday morning, quick and relatively painless. He never knew that the young woman whose hands he had saved had lived a full life, raised three children, worked as a nurse for forty years, and whispered his name with her last breath. Historians now mention it in a footnote. More than 400,000 German prisoners of war came under American custody during World War II.

The vast majority of victims were treated in accordance with the standards of the Geneva Convention: properly fed, housed, and cared for according to minimum requirements. Some, like Ila Dressler, received more humane treatment. These were not the stories that earned medals or made headlines. They were small moments, too discreet to change the course of the war, but which transformed lives forever.

They rebuilt trust slowly, person by person, over decades of reconciliation. These are the stories that, in the end, mattered most. March 1945, Texas. The hands of a young girl, covered in blood so white it was painful to look at. Beneath it, skin healed, cells divided, tissues regenerated, life persisted despite injury and adversity, and despite every reason to give up.

A medic worked with care and gentleness, tending to an enemy like a patient. A young girl accepted help from someone she had been taught to fear and understood that the propaganda was a lie. In this exchange, one human being cared for another across the vastness of war. Something changed. Wounds could heal. Scars would remain. But kindness was still possible.

Even in the darkest hours of human history, human beings could choose to be better than circumstances demanded. That choice resonated across decades, across lives, across an ocean and a war, and across all the hatred that should have made mercy impossible. Two people who never saw each other again carried that truth into a world that desperately needed to remember it.

Note: Some content was created using AI (AI and ChatGPT) and then reworked by the author to better reflect the historical context and illustrations. I wish you a fascinating journey of discovery!