Operation Swift: The Bloodiest Marine Ambush of the Vietnam War That You’ve Never Heard Of. NU

Operation Swift: The Bloodiest Marine Ambush of the Vietnam War That You’ve Never Heard Of

The Quaison Valley stretched across Kuang Nam and Kangtin provinces like a wound in the earth. A broad expanse of rice patties and villages flanked by mountains that rose dark and jungle covered on either side. The Vietnamese had farmed this valley for centuries, building their lives around the rhythm of the seasons and the flow of the rivers that fed their fields.

But by September 1967, the Quaison Valley had become something else entirely. It had become one of the most dangerous places in Vietnam, a killing ground where American Marines and North Vietnamese regulars fought battles of such intensity that the valley had earned a name among the men who served there, the Valley of Death.

The Marines had been operating in Quaison since 1966, conducting endless patrols and operations designed to deny the enemy access to the populated coastal areas. But denying the enemy anything in Quaison was nearly impossible. The valley was a natural corridor that connected the mountains of Laos to the coast, a highway for the infiltration of troops and supplies that the North Vietnamese had been using for years.

The villages that dotted the valley floor were filled with people whose loyalties were impossible to determine. Some supporting the government, some supporting the Vietkong, most simply trying to survive in a war that gave them no good choices. The terrain favored the defender in ways that made offensive operations a nightmare.

The mountains that bordered the valley were covered with triple canopy jungle so thick that visibility was measured in feet rather than yards. The enemy could watch American movements from these heights, could track patrols as they crossed the valley floor, could choose exactly when and where to strike. The rice patties that filled the valley bottom offered no cover for troops under fire, turning Marines into targets the moment shooting started.

The hedge and tree lines that bordered the patties provided perfect positions for ambush, allowing the enemy to achieve surprise at ranges so close that American firepower advantages meant nothing. The first marine division had been bleeding in quaison for more than a year. The names of the operations blurred together.

Colorado, Mon, Napa, dozens of others that resulted in casualties and body counts and reports of progress that never seemed to translate into actual security. The enemy remained no matter how many times the Marines swept through the valley. The villages remained contested no matter how many pacification programs were attempted. The infiltration continued no matter how many patrols were run and how many ambushes were set.

By early September 1967, intelligence indicated that the enemy presence in Quaison had grown significantly. The second NVA division had moved into the area, joining local Vietkong main force units to create a concentration of enemy strength that threatened to overwhelm the scattered marine positions. The intelligence was fragmentaryary, as intelligence in Vietnam always was.

But the pattern suggested that something big was building, that the enemy was preparing for operations that would exceed anything the valley had yet seen. The Marines of the Fifth Marine Regiment were tasked with responding to this threat. The Fifth Marines were veterans. Their battalions filled with men who had already survived months of combat and who harbored no illusions about what they were facing.

They knew the Quissson Valley. They had buried friends in the Quaison Valley, and now they were being sent back in to find and destroy an enemy force that might be larger and better prepared than anything they had encountered before. The operation that would become known as Swift began in the early morning hours of September 4th, 1967.

It would last only 4 days. In those 4 days, 127 Marines would be killed and hundreds more wounded. Companies would be overrun and nearly annihilated. Men would fight handto hand in the darkness, struggling to survive against an enemy that seemed to appear from nowhere and vanish just as quickly.

Operation Swift would become one of the bloodiest engagements of the entire Vietnam War. A concentrated burst of violence that demonstrated everything that was wrong with how America was fighting and everything that was right about the men who were doing the fighting. This is the story of those four days. It is a story of ambush and slaughter, of heroism and survival, of young men pushed beyond any limit they had imagined and asked to do things that should not have been possible.

It is a story of the valley of death and of the Marines who walked into it knowing that many of them would never walk out. The fifth marine regiment traced its lineage back to 1914 and its battle honors included some of the most storied engagements in American military history. Bellow Wood in World War I where Marines had earned the German nickname Toefl Hunden Devil Dogs.

Guadal Canal, Paleu, and Okinawa in World War II. The chosen reservoir in Korea where the regiment had fought its way through seven Chinese divisions in temperatures that reached 40 below zero. The fifth Marines had a tradition of being sent to the hardest places and asked to do the hardest things, and Vietnam was proving no exception.

The battalions that would fight Operation Swift were the First Battalion, Fifth Marines, and the Third Battalion, Fifth Marines. These were not fresh units filled with replacements, but seasoned formations whose men had already learned the brutal lessons that Vietnam taught. The company commanders and platoon leaders had survived long enough to know what worked and what did not, what kept men alive and what got them killed.

The sergeants and corporals who led the fire teams and squads had been tested in combat and had not been found wanting. The individual Marines who filled the ranks were a cross-section of America in 1967. Some were volunteers who had enlisted seeking adventure or escape from deadend lives in small towns and urban neighborhoods. Others were drafties who had been channeled into the Marine Corps by a system that seemed designed to ensure that the burden of the war fell disproportionately on those least able to avoid it. They came from every state

and every background, united only by the transformation that boot camp had imposed and the experiences they had shared since arriving in Vietnam. The average marine in the fifth regiment was 20 years old, though many were younger and a few were older. They were physically hardened by months of patrolling in terrain that demanded constant exertion and psychologically hardened by exposure to violence that would have been unimaginable in the lives they had lived before.

They had lost friends, had killed enemies, had seen things that they would never fully be able to describe to people who had not been there. They were not the same men who had stepped off the planes and ships that brought them to Vietnam. And they would never be those men again. The weapons they carried were the standard arament of Marine infantry in 1967.

The M16 rifle, still controversial and still prone to the jamming that had killed Marines in earlier battles, though procedures for cleaning and maintenance had improved. The M60 machine gun, beltfed and capable of providing the suppressive fire that could make the difference between survival and annihilation.

the M79 grenade launcher, which could drop explosive rounds on enemy positions at ranges beyond what handthrown grenades could achieve, and the mortars and artillery that provided fire support. The great equalizers that American forces relied on to overcome the enemy’s advantages in numbers and terrain. The Marines also carried equipment that the war had proven essential.

Multiple cantens for the water that the heat and humidity demanded. Ammunition in quantities that would have seemed excessive in training, but that combat had proven barely adequate. First aid, supplies that might save a life if a corman could not reach a wounded man quickly enough. and the personal items that provided what comfort they could.

Letters from home, photographs of girlfriends and families, small talismans that men believed might protect them from the random violence that claimed lives without reason or pattern. The officers who commanded these Marines faced challenges that no peaceime training could fully prepare them for.

The lieutenants who led platoon were often only a year or two older than the men they commanded, learning their trade in an environment where mistakes were paid for in blood. The captains who commanded companies had to make decisions that would determine who lived and who died, often with incomplete information and inadequate time.

The colonels and generals who planned operations did so from command posts that were far from the fighting, dependent on radio reports that could never fully convey the reality of what was happening on the ground. The enemy that the fifth Marines faced in Quaison was worthy of respect, though that respect was rarely acknowledged openly.

The second NVA division was a professional military formation whose soldiers had trained for years and who believed in their cause with a fervor that American troops often could not match. The local Vietkong main force units had been fighting in this valley for even longer knew every trail and every hiding place and could count on the support or at least the silence of many of the local population.

These were not the pajama clad gorillas of American propaganda, but disciplined soldiers who had learned their craft in a hard school and who had proven their willingness to die for their objectives. The collision between these forces in September 1967 would produce a battle of exceptional violence fought at ranges so close that the advantages of American technology largely ceased to matter.

It would be a battle of rifles and grenades and bayonets, of men killing each other at distances measured in feet, of courage and terror mixed together in ways that defied clean description. It would be Operation Swift. The initial phase of Operation Swift began on September 4th, 1967 when elements of the fifth Marines moved into the Quaison Valley to investigate reports of enemy activity.

The operation was conceived as a routine sweep, the kind of search and destroy mission that Marines conducted constantly throughout their area of operations. Intelligence suggested enemy presence, but could not confirm its strength or dispositions. The Marines would advance into the valley, find whatever was there, and deal with it using the firepower and tactical skill that had characterized their operations throughout the war.

Delta Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marines, moved out early on the morning of September 4th, advancing across the valley floor toward the village of Dong Son. The day was typical for Kuang Nam Province in September. Hot and humid, the sky a hazy white that filtered the sun without reducing its intensity. The Marines moved in formation, maintaining the intervals and security that experience had taught them were essential, watching the tree lines and hedge for any sign of the enemy.

The valley floor was a patchwork of rice patties separated by earth and dikes and bordered by vegetation that could conceal anything. The patties themselves were flooded, ankle deep water that sucked at boots and made movement exhausting. The mud beneath the water was treacherous, sometimes firm enough to support a man’s weight, and sometimes soft enough to swallow him to the knee.

Every step was an effort, and the Marines were sweating through their uniforms before they had covered the first kilometer. The villagers they encountered seemed to melt away before them, disappearing into their homes or simply vanishing into the landscape. This was not unusual. The people of the Quaison Valley had learned that proximity to American patrols was dangerous, that the fighting that often followed such patrols did not discriminate between combatants and civilians.

Their absence was not necessarily evidence of enemy presence, but neither was it reassuring. The Marines moved forward with heightened alertness. Sensing that something was wrong without being able to identify what. The first indication that something was wrong came without warning. The point man raised his fist, the signal to halt.

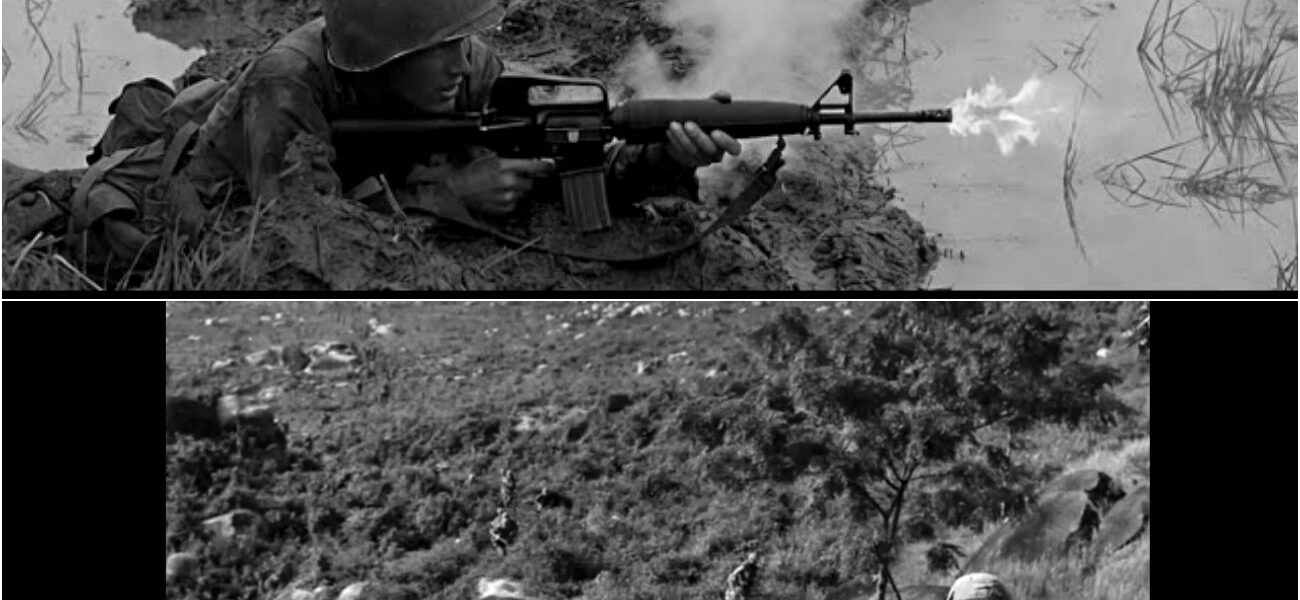

The patrol froze, every man dropping to a knee, weapons ready, eyes scanning the terrain ahead. The silence stretched, tension building with each passing second. And then the world exploded. Contact came in the early afternoon as Delta Company approached a treeine that bordered a cluster of huts. The first shots cracked across the patty with a distinctive sound of AK47 fire.

Rounds snapping past the Marines before anyone had time to react. The sound was followed instantly by more fire. A crescendo of automatic weapons that seemed to come from everywhere at once. Men dove for the patty dikes, seeking whatever cover the lowear and BMS could provide. While the volume of fire increased to a level that suggested this was no chance encounter with a few gorillas, the initial volley cut down Marines who had no chance to react.

A rifleman in the lead squad was hit three times before he reached the ground, his body jerking with each impact. His fire team leader turned to help him and was hit in the throat, the round tearing through his larynx and dropping him into the patty water that instantly turned red. A machine gunner tried to get his M60 into action and was killed before he could fire a single burst.

The valuable weapon falling into the mud beside his body. The Marines returned fire immediately, sending rounds into the treeine where muzzle flashes revealed enemy positions. The M60 machine guns opened up, their heavier reports providing base notes to the higher crackle of rifle fire. The company commander was on the radio calling for fire support, trying to assess a situation that was changing by the second.

This was not a minor contact. This was something much bigger. The enemy had prepared the position carefully, as they always did. The treeine was honeycombed with fighting holes and bunkers concealed so well that the Marines could not see them even as they took fire from their occupants. The NVA soldiers who manned these positions were disciplined, firing in controlled bursts and shifting locations to avoid giving the Americans fixed targets.

They had waited until the Marines were in the open, committed to their advance before initiating contact. It was a textbook ambush and Delta Company had walked into it. The first casualties came within minutes of the initial contact. A marine fell in the patty, hit by rounds that caught him before he could reach cover.

Another was struck as he tried to move to a better position. The bullets spinning him around and dropping him in the shallow water. The calls for Corman began. The desperate shouts that meant men were bleeding and dying. That the abstract danger of combat had become immediate and personal. The company commander ordered his platoon to maneuver to find the enemy’s flanks and develop the situation.

But maneuvering across the open patties under fire was almost impossible. Every movement drew additional fire. The enemy seemed to be everywhere, firing from positions that the Marines could not identify or suppress. The Americans were pinned, unable to advance and unwilling to retreat, bleeding under fire that showed no sign of slackening.

Artillery was called and the rounds began falling on the enemy positions. Geysers of earth and smokes erupting along the tree line. But the enemy had prepared for this as well, digging deep and accepting the bombardment as the price of maintaining contact. The artillery killed some, but others remained, continuing to fire even as the shells fell among them.

The American firepower advantage that was supposed to guarantee victory was proving insufficient against an enemy who had learned to survive it. Delta Company was in trouble. The first engagement of Operation Swift had barely begun, and already the situation was spiraling toward disaster. As the afternoon wore on, the situation facing Delta Company grew increasingly desperate.

What had begun as a chance contact was revealing itself to be something far more serious. A deliberate ambush by a force that significantly outnumbered the Marine Company. The enemy was not withdrawing in the face of American firepower, as they often did, but maintaining pressure, pouring fire into positions that were becoming increasingly untenable.

The casualties mounted with terrible speed. Marines who had survived months of combat were hit by rounds that seemed to come from everywhere at once. The corman moved from casualty to casualty, exposing themselves to fire that did not discriminate between those providing aid and those needing it. The wounded cried out for help, their voices mixing with the continuous crack of rifle fire and the heavier thud of grenades and mortars.

The company commander, Captain Gene Grunberg, was trying to coordinate a response to a threat he could not fully see or understand. His radio was alive with reports from his platoon leaders, each describing a situation that seemed to be deteriorating independently. First platoon was heavily engaged on the left, taking fire from positions they could not suppress.

Second platoon was trying to move forward, but was pinned by machine gun fire that cut down anyone who rose above the Patty dikes. Third platoon was attempting to flank the enemy positions, but was itself taking fire from an unexpected direction. The realization dawned slowly, but with increasing certainty.

Delta Company had not stumbled into a local Vietkong unit, but into a much larger force, possibly an entire NVA battalion that had been waiting for exactly this kind of opportunity. The enemy had drawn the Marines into a kill zone and was now methodically destroying them, exploiting their exposure in the open patties and their inability to bring their advantages in firepower fully to bear.

The call went out for reinforcements. Lieutenant Colonel Peter Gruenberg, commander of First Battalion, Fifth Marines, ordered his remaining companies to move toward Delta Company’s position. But moving reinforcements across the Quaison Valley was not a simple matter. The terrain that trapped Delta Company would trap anyone who tried to reach them.

The same enemy who had ambushed the first company would be waiting for the others. The rescue mission was itself an invitation to further disaster. Echo Company was the first to move, advancing across the patties from their own positions toward the sound of the fighting. They had not gone far before they too came under fire. Rounds cracking past from positions that had not revealed themselves until the Marines were in the open.

The enemy had prepared multiple ambush sites, anticipating that the Americans would reinforce their trapped comrades and planning to destroy the reinforcements as well. The battlefield was expanding, the violence spreading across the valley floor like fire through dry grass. What had been one company in contact was now two, then three, each facing enemy forces that seemed to have materialized from nowhere.

The radio traffic became a cacophony of calls for fire support, reports of casualties, desperate requests for ammunition, and medical supplies. The command post struggled to keep track of a situation that was changing faster than reports could convey. The close air support that was supposed to provide the decisive edge in such situations was slow to arrive and difficult to employ.

The proximity of friendly and enemy forces made bombing runs dangerous with the risk of hitting marines as high as the risk of hitting the enemy. When aircraft did arrive, they had difficulty identifying targets in the tree lines and hedge. their pilots unable to distinguish between the positions that needed to be destroyed and the ones that needed to be protected.

The artillery continued to fall, but its effects were limited by the same constraints that hampered air support. The enemy had positioned himself so close to the Marines that calling fire on his positions meant calling fire dangerously close to friendly troops. The artillery forward observers who directed the fire were working at the edge of what was possible, trying to drop shells on enemies who were sometimes only 50 m from the marines they were trying to kill.

As the sun began to sink toward the mountains that bordered the valley, the situation had not improved. Multiple companies were now engaged, all of them taking casualties, none of them able to break the enemy’s grip. The Marines were fighting for survival, and survival was not guaranteed. The darkness that was coming would make everything worse.

The medevac helicopters made attempt after attempt to reach the wounded. Each approach met with fire that drove them back. The pilots circled, watching the tracer rounds reach up toward them, knowing that men were dying below because they could not land. Some pilots made the approach anyway, accepting the risk because they could not accept the alternative.

One helicopter was hit and forced to withdraw trailing smoke. Another landed despite the fire. its crew chief pulling wounded Marines aboard while bullets sparked off the fuselage. The radio traffic was a constant stream of desperation. Company commanders reporting casualties they could not evacuate. Platoon leaders requesting ammunition they could not receive.

Forward observers calling fire missions that fell dangerously close to friendly positions because the enemy was that close. The command net was saturated with the sounds of a battle that was spinning out of control. The wounded who could not be evacuated lay where they had fallen or where their buddies had dragged them. The corman moved among them doing what they could with supplies that were running low.

Morphine was administered to men whose pain exceeded what anyone should have to bear. Bandages were applied to wounds that needed surgery. IV lines were started with fluids that could not replace the blood that had been lost. The cormen knew that some of the men they were treating would die, that their efforts were only delaying the inevitable, but they worked anyway because working was all they could do.

The smell of the battlefield was something that those who experienced it would never forget. The copper scent of blood mixing with the cordite smell of gunfire. The bodily odors of men who had soiled themselves in terror or in death. The particular smell of exposed intestines from men with abdominal wounds.

The rot that began almost immediately in the tropical heat. The bodies of the dead already beginning to decompose even as the living fought around them. The tropical darkness came quickly. The sun dropping behind the western mountains and plunging the valley into a blackness that was almost absolute for the Marines scattered across the Quaison Valley floor.

The darkness brought both relief and terror. Relief because the enemy’s fire slackened as visibility disappeared. Terror because the darkness belonged to the enemy who had spent years learning to use it as a weapon. The companies that had been engaged throughout the afternoon used the darkness to consolidate their positions, to collect their wounded, to count their dead.

The casualties were staggering. Delta Company had lost dozens of men killed and wounded. Its ranks so depleted that its ability to continue as an effective fighting force was in question. Echo Company had suffered as well, along with the other units that had moved to reinforce. The battalion was bleeding out in the darkness of the Quaison Valley.

The wounded presented a crisis that threatened to overwhelm the medical resources available. Men with traumatic amputations, with penetrating abdominal wounds, with injuries that required immediate surgical intervention, lay in the darkness, waiting for evacuation that might not come. The corman did what they could with the supplies they had.

But what they had was not enough. Men who might have survived with prompt treatment died because the helicopters could not fly into a hot landing zone in the darkness. The dead were collected and placed in rows, their bodies covered with ponchos or whatever material was available. The Marines who performed this duty worked in silence, recognizing faces that had been alive hours before, handling bodies that still held the warmth of life.

There was no time for grief, no opportunity to process what was happening. The dead were handled with as much dignity as circumstances allowed and then set aside so that the living could focus on staying alive. The enemy was not idle during the night. The NVA soldiers who had conducted the ambush used the darkness to reposition, to reinforce, to prepare for the continuation of the battle that would come with dawn.

They moved through the valley with the confidence of men who knew the terrain intimately, who had rehearsed these movements and who understood exactly what they were trying to achieve. They were not interested in breaking contact and withdrawing. They were interested in destroying the marine force that they had trapped.

The probing attacks began around midnight. Small groups of NVA soldiers moved toward the Marine perimeters, testing the defenses, looking for gaps that could be exploited. The Marines fired at sounds and shadows, at movement that might be real or might be imagined. The night was punctuated by bursts of fire that illuminated nothing and revealed less.

Each exchange adding to the tension that was already almost unbearable. The command post worked through the night trying to arrange the reinforcements and support that would be needed when morning came. Additional battalions were being alerted. Helicopter assets were being marshaled. Artillery was being repositioned to provide better coverage.

But these preparations took time, and time was something that the trapped Marines did not have in abundance. The men in the perimeters waited for dawn with the desperate hope of men who knew that the coming day would bring more fighting and more dying, but who could not face the alternative of being overrun in the darkness.

They checked their weapons, counted their remaining ammunition, talked in whispers to the men beside them. Some prayed. Some wrote letters that they hoped would reach home if they did not. Some simply stared into the darkness, trying to see an enemy they knew was out there, preparing for the assault that might come at any moment.

The hours passed with agonizing slowness. The darkness seemed to last forever. Each minute stretching toward infinity as men waited for the light that would reveal what they faced. The sounds of the night, the insects, and the distant artillery, and the occasional burst of fire created a soundtrack of tension that wore on nerves already frayed to breaking.

And then finally, the eastern sky began to lighten. The darkness faded to gray and the shapes of the valley emerged from the night. The Marines could see again, could identify targets and threats, could bring their weapons to bear on enemies that were no longer invisible. The second day of Operation Swift was about to begin.

The Marines ate what breakfast they could stomach. Cold rations that tasted like cardboard and sat heavy in stomachs that were already churning with anxiety. They checked their weapons obsessively, ensuring that magazines were full and chambers were clear, that bayonets were sharp and grenades were secure. They looked at the faces of the men around them, and wondered which of them would still be alive when the day ended.

The war morning mist that lay across the valley floor began to lift as the sun climbed higher, revealing terrain that looked deceptively peaceful. The patties sparkled with water that caught the light. The tree lines were green and still. Birds moved through the vegetation, their calls providing a soundtrack that seemed to belong to a different world than the one the Marines inhabited.

The contrast between the beauty of the landscape and the horror of what had happened there was almost obscene. The morning of September 5th, 1967 brought a brief period of relative calm as both sides assessed the situation and prepared for the fighting that would inevitably resume. The Marines used the light to evacuate their most seriously wounded helicopters darting in and out of landing zones that had been cleared during the night.

The dead were collected more thoroughly now, their bodies prepared for transport to the rear where they would be processed and eventually sent home. The reinforcements that had been promised during the night were beginning to arrive. Additional companies from the fifth marines moved into the valley along with elements of the third battalion that had been held in reserve.

The helicopter assets that had been marshaled during the night were available for troop lifts and fire support. The Americans were preparing to counterattack to seize the initiative from an enemy who had dominated the first day’s fighting. But the enemy had his own plans for September 5th. The attack came midm morning as Bravo Company, First Battalion, Fifth Marines moved across open ground toward positions that intelligence believed were held by enemy forces.

The company had been briefed on the previous day’s fighting and was advancing with appropriate caution, maintaining security and ready to react to contact, but nothing could have prepared them for what they encountered. The NVA opened fire from positions that had been invisible until the moment they began shooting.

The volume of fire was staggering. Hundreds of rounds per minute pouring into the Marine formation from multiple directions. Men fell in the first seconds, cut down before they could react to a threat that seemed to materialize from the Earth itself. The company’s advance stopped, then reversed, then collapsed into desperate individual struggles for survival.

The killing ground that the enemy had prepared was a masterpiece of tactical planning. Fields of fire had been cleared and concealed. Positions had been dug and reinforced and connected by trenches that allowed movement without exposure. Machine guns had been cited to create interlocking bands of fire that left no dead space.

No safe ground where a man could find protection. The Marines had walked into a trap that had been designed specifically to destroy them. The sounds that filled the air were the sounds of slaughter. The continuous rattle of AK-47s on full automatic, their distinctive report identifying them as enemy weapons. The heavier thud of RPD machine guns, their rounds cutting through vegetation and flesh with equal indifference.

The crack of American M16s answering, sporadic and desperate compared to the disciplined volleys of the enemy. The screams of wounded men high and terrible, cutting through the den in moments that seared themselves into memory. Marines died in every conceivable way. Some were killed instantly, rounds striking heads or hearts and ending lives between one heartbeat and the next.

Others died slowly, bleeding out from wounds that might have been survivable with immediate treatment, but that were fatal in the chaos of the ambush. Some died trying to help others. Cormen and buddies who exposed themselves to reach the wounded and paid the price for their courage. A few died by their own hands. Grenades detonated in final acts of defiance when capture or slow death seemed the only alternatives.

The bodies accumulated in patterns that would later be analyzed, but that meant nothing to the men who were creating them. Marines fell in the open patties, their bodies floating face down in the shallow water. They fell behind the dikes where they had sought cover, killed by fire that found them anyway.

They fell in the tree lines where they had tried to close with the enemy. Their advances stopped by fire too intense to push through. The dead were everywhere, marking the progress of a battle that had become a massacre. The wounded who survived the initial moments faced agonies that tested the limits of human endurance. Men with shattered legs dragged themselves toward cover, leaving trails of blood that enemy soldiers could follow.

Men with abdominal wounds tried to hold their intestines inside their bodies, their hands slipping on viscera that refused to stay contained. Men with head wounds lay still, their breathing the only sign that life remained, waiting for help that might never come. The company commander was hit early in the engagement.

His leadership lost at the moment it was needed most. The executive officer took command and was hit minutes later. The platoon commanders fell one by one, targeted by enemy fire that seemed to know exactly who to kill. The sergeants stepped up and the sergeants fell. The corporals took over and the corporals fell. The chain of command disintegrated under fire that showed no mercy and made no mistakes.

The casualties on September 5th exceeded anything the battalion had experienced. Bravo Company was effectively destroyed as a fighting unit within the first hour. Its dead and wounded carpeting the ground over which they had advanced. The survivors huddled behind whatever cover they could find, unable to move forward or backward, taking fire from enemies they could not see and could not suppress.

The command structure began to collapse under the weight of the casualties. Officers and NCOs were targeted specifically. The enemy recognizing the value of eliminating leaders who could coordinate resistance. Radio operators were hit. Their antennas marking them for fire that arrived with precision that suggested careful planning.

The Marines found themselves leaderless, weaponless, fighting as individuals rather than as the coordinated unit they had been trained to be. The hand-to-hand fighting that day reached levels of intensity that veterans would remember for the rest of their lives. NVA soldiers emerged from their positions to engage Marines at close range, using bayonets and grenades and rifle butts in struggles that were decided by strength and will rather than tactics or firepower.

Men died face to face with their killers, seeing the eyes of the enemy in the moment of their deaths. The intimacy of this combat was psychologically devastating in ways that firefights at longer ranges were not. A marine might look into the face of a man he was killing might see the fear and determination that mirrored his own. Might watch the life leave those eyes as his bayonet found its mark.

These images would return unbidden for years and decades, surfacing in dreams and quiet moments, forcing confrontations with what had been done and what it had cost. The noise of close combat was different from the noise of firefights. There was grunting and cursing and screaming in both English and Vietnamese.

There was the thud of bodies colliding, the crack of bones breaking, the wet sounds of blades entering flesh. There was the heavy breathing of men exerting themselves to the limits of their endurance, fighting not just to win, but to survive another second, another minute, another breath. The smell was close and personal.

the sweat and blood and fear of men who were killing each other at arms length. Marines could smell their enemies, could smell the fish sauce and newok mom that flavored their meals. Could smell the particular odor of bodies that had lived differently than American bodies lived. The enemy could smell them, too. The different sweat and different food and different fear of young Americans far from home.

Grenades exploded among men who were too close together to avoid the blasts. Marines threw grenades at positions only meters away, diving for cover as the explosions sent shrapnel through air that was already thick with flying metal. The enemy threw grenades back. Chcom grenades with their distinctive wooden handles. Explosions that killed Americans and Vietnamese alike in the chaos of the melee.

One Marine, Sergeant Lawrence Peters, threw himself on a grenade to save the men around him, absorbing the blast with his body and dying so that others might live. His sacrifice was one of many that day. Acts of courage that emerged from the chaos because courage was all that some men had left to give.

The medal that Peters would receive postumously, the Navy Cross, could not capture what he had done or why he had done it. It was simply the military’s way of acknowledging that extraordinary things had happened in the Quaison Valley. The evacuation of casualties became almost impossible. Helicopters that attempted to land in the zone were driven off by fire so intense that approaching the ground meant almost certain destruction.

The wounded lay where they had fallen, waiting for help that could not reach them, dying from wounds that might have been survivable if treatment had been available. The coremen who tried to reach them were themselves becoming casualties. Their selflessness no protection against bullets that did not discriminate.

The dying took hours, sometimes men clinging to life long past the point when death would have been a mercy. They called for their mothers, as dying men often did, reverting to the most fundamental relationship in moments of extremity. They called for water, their throats parched by blood loss and shock.

Water that their buddies gave them, even though they knew it might do more harm than good. They called for help that could not come, for medevacs that could not land, for miracles that did not happen. The men who watched their friends die were themselves being transformed by the experience. Something hardened inside them.

Some protective shell that formed around the emotions that would otherwise have been unbearable. They learned to look at the dying without feeling or at least without showing feeling. Because showing feeling was a luxury that the battlefield did not allow. They would pay for this hardening later in the years and decades after the war, but for now it was necessary.

The ammunition situation grew increasingly critical as the afternoon wore on. Marines were running low on magazines, low on grenades, low on everything they needed to continue fighting. The resupply that had been promised was delayed by the same fire that prevented evacuation. Men scred rounds from the dead and wounded, redistributing ammunition to those who could still use it.

Some fixed bayonets, preparing for the possibility that they would have to fight without bullets. By late afternoon on September 5th, the American situation in the Quaison Valley had reached a crisis point. Multiple companies had been mauled, their casualties running into the hundreds. The enemy showed no sign of withdrawing, continuing to pour fire into positions that were becoming increasingly untenable.

The battle that had begun as a routine sweep was becoming one of the bloodiest marine engagements of the entire war. Darkness would come again soon, and with it another night of terror. The magnitude of the disaster unfolding in the Quaison Valley had reached the third Marine Amphibious Force headquarters, and the response was immediate.

Additional battalions were ordered into the fight. Aviation assets were concentrated, and artillery was masked to provide the fire support that the trapped units desperately needed. The operation was no longer about finding and destroying enemy forces. It was about rescuing Marines who were fighting for survival. The commanders at division and force level understood that they faced a situation that could become even worse than it already was.

The enemy had demonstrated the ability to ambush and destroy American units in the Quaison Valley if the relief forces were themselves ambushed if the disaster was compounded rather than remedied. The result could be a catastrophe of historic proportions. The decision to send more men into the valley was not made lightly.

The third battalion, Fifth Marines, had been moving toward the battle throughout September 5th. Its companies advancing through terrain that might contain additional ambushes that might be seated with the same traps that had snared the other battalions. The men of 35 knew what they were walking into. They had heard the radio traffic, had seen the helicopters returning with wounded, had received the reports of casualties that were almost beyond belief.

They advanced anyway because Marines did not abandon other Marines. The advance of the relief force was conducted with extreme caution. Point men moved slowly, searching for the signs of ambush that might give warning before contact was made. Flank security pushed out into terrain that might conceal enemy forces. The formation was dispersed to minimize casualties if fire was received.

Every lesson that had been learned in two days of bloody fighting was applied to the movement that might determine whether the trapped Marines lived or died. The link up between the relief force and the trapped companies was achieved late on September 5th as the light was beginning to fade. The scene that greeted the fresh troops was one of carnage that exceeded anything most of them had imagined.

Bodies lay in the patties and along the dikes, some covered with ponchos and some not. Their positions marking the progress of the day’s fighting. The wounded filled every available space. Their injuries ranging from minor to mortal. All of them waiting for evacuation. that was still not possible. The perimeter that had been established was pathetically thin, held by men who had been fighting for two days without rest, whose ammunition was running low and whose leaders were dead or wounded.

The relief force integrated into this perimeter, thickening the defenses and providing the first real hope that the position might be held through another night. The fresh ammunition and supplies that they brought were distributed among men who had been counting rounds and wondering how long they could hold out. The consolidation of the perimeter was conducted under intermittent fire.

The enemy reminding the Marines that he was still present even as the relief force arrived. Positions were dug deeper. Fields of fire were cleared. Claymore mines were in place to cover the most likely avenues of approach. The work was exhausting, but it was also necessary. The perimeter had to be strong enough to survive whatever the night might bring.

The Marines, who had survived the ambush and the counterattack, looked at the fresh troops with expressions that mixed relief and something else, something harder to define. The relief force had not been through what they had been through. The new arrivals still had the look of men who had not yet been tested, whose confidence had not yet been shattered by experiences that exceeded anything training could prepare you for.

The veterans of the days fighting knew something that the relief force would soon learn. The enemy in this valley was not the enemy they had expected. The command structure was rebuilt during the brief respit that the relief forces arrival provided. Officers and NCOs from fresh units took over positions that had been left vacant by casualties.

Communications were restored with higher headquarters. The situation was assessed with something approaching clarity for the first time since the initial contact. The picture that emerged was grim. Multiple companies had been mowled. Casualties were in the hundreds, and the enemy remained capable of continuing the fight.

The night of September 5th, the 6th, was tense, but quieter than the previous night had been. The enemy had suffered casualties as well, losses that were significant, even if they were less catastrophic than what the Marines had experienced. The NVA commanders were reassessing their situation, deciding whether to continue the attack or withdraw before American reinforcements became overwhelming.

The probe attacks continued, but the major assault that the Marines feared did not materialize. The evacuation of wounded continued throughout the night. Helicopters making dangerous approaches to landing zones that were still under sporadic fire. The pilots who flew these missions displayed courage that matched anything shown by the men on the ground, bringing their aircraft into conditions that defied reasonable expectations of survival.

Each helicopter that lifted off with wounded men represented lives saved. futures preserved. Families that would not receive the telegrams that so many others would receive. The dead were collected and arranged for evacuation as well, though they had lower priority than the living. The process of identifying bodies, of recording the names and circumstances of their deaths, of preparing them for the journey home was conducted with as much dignity as circumstances allowed.

For some of the dead, identification was difficult or impossible. Their bodies damaged beyond recognition by the weapons that had killed them. The Marines who had survived the first two days of Operation Swift were changed in ways that would never be fully undone. They had seen friends killed at close range, had fought enemies they could sometimes touch, had experienced a level of violence that exceeded anything they had been prepared for.

Some would process these experiences successfully, integrating them into lives that would continue to have meaning and purpose. Others would carry wounds that no surgery could heal, would struggle for years or decades with what they had seen and done. The morning of September 6th brought the hope that the worst was over. The enemy’s fires had slackened.

His pressure had eased and the possibility of breaking free from the trap he had set seemed real. But the battle was not yet finished. The NVA forces in the valley had taken losses, but had not been destroyed. They remained capable of fighting and they had not yet decided to withdraw. The third day of Operation Swift would determine whether the Marines had survived or merely delayed their destruction.

September 6th, 1967 began with the first sustained American offensive action since the battle had started. The reinforced Marine force, now comprising elements of multiple battalions, began moving to clear the enemy positions that had caused so much destruction over the previous 2 days. The advance was cautious, painfully aware of the cost that had been paid for insufficient caution.

But it was an advance nonetheless. The Marines were no longer simply trying to survive. They were fighting back. The enemy positions that the Marines approached had been prepared with the same thoroughess that had characterized the ambush sites. Bunkers and trenches crisscross the tree lines, providing cover for defenders who were not ready to abandon the fight.

The NVA soldiers who man these positions had not broken under the artillery and air attacks of the previous days. They remained disciplined, ready to kill more Americans if the opportunity presented itself. The fighting on September 6th was characterized by close quarters combat as Marines cleared positions that could not be reduced by firepower alone.

Bunkers had to be approached and destroyed individually, their occupants killed or driven out by grenades and direct fire. Trenches had to be entered and cleared. Their defenders engaged at ranges so close that bayonets were sometimes the weapons of choice. The skills that the Marines had developed over months of combat were tested to their limits.

The bunker clearing operations were among the most dangerous tasks that infantry could be asked to perform. A bunker might contain a single defender or a dozen. Might be connected to other positions by trenches or tunnels. Might be booby trapped against exactly this kind of assault. The Marines who approached these positions knew that they might be killed in the next seconds, that the darkness ahead might conceal death that was waiting for them.

The technique for clearing bunkers had been developed through bloody experience. Grenades first thrown through the aperture or rolled through any opening that could be found. Then suppressive fire. Rounds poured into the opening to keep any survivors pinned while assaulting troops moved to the entrance. Then entry, a moment of total commitment when the marine went through the door and into whatever waited inside.

Then the killing, close and personal, done in darkness and smoke and the confusion of combat. The men who specialized in this work developed reputations that spread through the battalion. They were respected and feared. Their willingness to do the most dangerous job, marking them as either exceptionally brave or exceptionally crazy. Some of them were killed.

the odds catching up with them despite their skill. Others survived, carrying the memories of what they had done in those dark spaces, the faces of men they had killed at arms length. The casualties continued to mount, though at a slower rate than on the previous days. Men fell to fire from positions they had not detected, to booby traps that had been in place during the night, to the random misfortunes that war distributed without logic or fairness.

Each casualty was a tragedy for someone, a son or husband or brother or friend who would not be coming home. But the overall trajectory of the battle had shifted. The Marines were now the hunters rather than the hunted. The enemy began to withdraw during the afternoon of September 6th. The NVA commanders had achieved significant results, inflicting casualties on the Americans that would be felt for months.

But they recognized that continuing the fight risked the destruction of forces they could not easily replace. The withdrawal was conducted with professional skill. Rear guards covering the movement of the main body. Trails booby trapped to delay pursuit. Positions prepared to ambush anyone who followed too aggressively. The Marines pursued but carefully.

The lessons of the previous days had been learned in blood, and no one was eager to walk into another ambush. The advance cleared enemy positions that had been abandoned, capturing equipment and documents that would provide intelligence value, but making limited contact with the withdrawing enemy force.

The NVA was escaping, melting back into the mountains and jungle that had sheltered them before the battle began. By the evening of September 6th, the active fighting was essentially over. The enemy had broken contact and withdrawn. The Marines held the ground where so many had died. The rice patties and tree lines that would forever be associated with Operation Swift.

The valley was quiet in a way it had not been for days. The absence of gunfire almost disorienting after the constant violence of the battle. The cost was becoming clear as the final accounting began. The Marines had suffered 127 killed and over 300 wounded in just 4 days of fighting. Several companies had been effectively destroyed.

their ranks so depleted that they could no longer function as independent units. The casualty rate for units engaged was among the highest of any operation in the entire war. A concentration of death and injury that reflected the intensity of what had happened. The enemy’s losses were harder to assess as they always were in Vietnam.

Body counts were reported, numbers that suggested the enemy had suffered even more heavily than the Americans. But these numbers were notoriously unreliable. What was certain was that the NVA force had withdrawn intact. Its cohesion and discipline maintained even in retreat. The Marines had survived, but they had not destroyed the enemy that had ambushed them.

The helicopters came throughout the evening and into the night, evacuating the last of the wounded and the accumulated dead. The men who remained in the valley worked through the darkness, policing the battlefield, collecting equipment, preparing for whatever mission would come next. They were exhausted in ways that transcended physical fatigue.

Their minds and spirits drained by experiences that would take years to fully process. Operation Swift was ending. The long process of understanding what had happened was just beginning. The Marines who had survived the 4 days of Operation Swift were not the same men who had entered the Quaison Valley. They had been transformed by experiences that exceeded anything they had imagined, that tested them in ways that peacetime life never could.

Some would look back on the battle as the defining moment of their lives, the crucible that revealed who they truly were. Others would spend the rest of their lives trying to forget. The physical toll was immediately visible. The surviving Marines were gaunt and holloweyed. Their faces aged by days that had felt like years.

They moved with the exhaustion of men who had pushed far beyond their limits, who had found reserves of endurance they did not know they possessed and had depleted them completely. They needed sleep and food and medical attention. And they needed something else that was harder to provide. They needed to process what had happened to find some way to integrate the experience into lives that had to continue.

The psychological toll was less visible but equally profound. The men who had fought through Operation Swift carried memories that would surface unbidden for the rest of their lives. the faces of friends who had died, the sounds of the battle at its height, the smells that had filled the air as men bled and died and rotted in the tropical heat.

These memories were not like other memories. They were vivid and intrusive, capable of transporting the men who carried them back to the valley as if no time had passed at all. Some of the survivors would develop what would later be called post-traumatic stress disorder, though that term did not yet exist in 1967. They would experience nightmares and flashbacks, would flinch at sounds that reminded them of combat, would struggle to form relationships with people who could not understand what they had experienced.

They would self-medicate with alcohol and drugs, trying to dull pain that seemed impossible to treat. Some would take their own lives, casualties of Operation Swift, who died years or decades after the battle ended. The Quaison Valley in the days following Operation Swift was a haunted place. The Marines who remained, those who had survived and those who had arrived as reinforcements, moved through a landscape that bore the scars of intense combat.

Shell craters pocked the patties. Bunkers gaped open where they had been destroyed. The tree lines were torn and splintered by the explosives that had been poured into them. And everywhere, if you knew where to look, there were the traces of what had happened. Blood stains on the dikes, equipment abandoned in flight, the detritus of a battle that had consumed everything in its path.

The smell of death lingered in the valley for days after the fighting ended. The bodies had been removed, but the blood that had soaked into the earth, the viscera that had been scattered by explosions, the human waste that had been released in death, all of these remained, decomposing under the tropical sun and filling the air with an odor that the Marines who experienced it would never forget.

It was the smell of what they had done and what had been done to them, a physical reminder of the cost that had been paid. The recovery of equipment and weapons continued long after the battle. Rifles and machine guns that had been dropped in the patties were retrieved and cleaned. Radios that had been abandoned were collected and cataloged.

Personal effects that had belonged to the dead were gathered with as much care as circumstances allowed to be shipped home to families who would treasure these last connections to sons and brothers they would never see again. The local population, those who had survived and remained, emerged slowly from wherever they had hidden during the fighting.

Their villages had been devastated, caught between forces that did not particularly care what happened to civilians. Homes had been destroyed, crops had been burned, and the delicate fabric of rural life had been torn in ways that would take years to repair, if they could be repaired at all. The villagers looked at the Americans with expressions that were impossible to read, that might have contained fear or hatred, or simply the exhausted resignation of people who had seen too much.

The Marines who had fought Operation Swift were rotated out of the valley as quickly as logistics allowed. Fresh units moved in to continue the mission, to patrol the same ground where so many had died, to face an enemy who would return as surely as the seasons changed. The war did not pause to honor the dead or comfort the living.

The war continued, demanding more operations, more patrols, more young men to feed into the machinery of attrition that neither side could seem to break. The survivors carried their experiences out of the valley and into the rest of their lives. Some would serve additional months in Vietnam, surviving subsequent operations that seemed almost anticlimactic after what they had experienced.

Others were wounded in ways that required evacuation, their war ending in hospitals where they would spend weeks or months recovering from injuries that would mark them forever. A few were so damaged psychologically that they could no longer function, their minds having reached a limit beyond which continued service was impossible. The memory of Operation Swift would persist long after the operation itself had ended.

The men who had been there would remember specific moments with a clarity that time could not diminish. The face of a friend who had died beside them, the sound of a particular weapon, the smell of the valley in those September days. These memories would surface unbidden for years and decades, triggered by stimuli that had nothing to do with Vietnam, but that somehow connected to the experiences they could not forget.

The anniversaries of the battle would be observed by those who survived. Gatherings that grew smaller each year as age claimed those whom the war could not. At these reunions, men who had shared the worst experience of their lives would reconnect, would remember the dead and celebrate the living, would try to convey to each other an understanding that could not be shared with anyone who had not been there.

The bonds formed in the Quaison Valley were bonds that nothing could break. The military processed the operation in its own way, producing afteraction reports and analyses that tried to extract lessons from what had happened. The reports documented the tactical details, the timelines and unit movements and casualty figures that could be reduced to numbers and charts.

They identified mistakes that had been made and suggested improvements for future operations. They did what military reports were supposed to do, creating a record that could be studied and learned from. But the reports could not capture what Operation Swift had actually been like for the men who had fought it.

The terror of the ambush, the desperation of the night, the chaos of the counterattack. These experiences defied the clinical language of official documentation. The reports recorded that 127 Marines had been killed, but they could not convey what those deaths had meant to the men who had witnessed them, to the families who would receive the notifications, to the communities that would never see their sons and brothers again.

The Quaison Valley would continue to be contested for years after Operation Swift. The enemy would return as he always did, and the Marines and later the army would continue to fight him in the same terrain where so many had already died. The valley would consume more lives, add more names to the wall that would eventually be built in Washington, generate more afteraction reports that would try to make sense of violence that ultimately made no sense at all.

Operation Swift became one of many operations, one battle among hundreds that collectively constituted the American experience in Vietnam. Its name was remembered by those who had fought it but faded from wider memory as the war continued and other battles demanded attention. The dead of Operation Swift joined the growing roster of Americans killed in a war that seemed to have no end.

Their sacrifices honored in the abstract, but often forgotten in the particular. Among the carnage of Operation Swift, there were acts of heroism that deserved recognition. Even if the circumstances that demanded them, deserved condemnation. The medals that were awarded afterward, the Navy crosses and silver stars and bronze stars, marked moments when individual Marines had done things that exceeded any reasonable expectation that demonstrated the capacity for selflessness that combat sometimes revealed.

The criteria for heroism in combat were simple, but almost impossible to meet. A willingness to risk one’s own life for others demonstrated an action that went beyond what duty required. Every Marine in the Quaison Valley was risking his life simply by being there. But some took risks that exceeded even that baseline. That put them in positions where survival was almost impossible, but where their actions might save others.

These men were the heroes of Operation Swift. Sergeant Lawrence Peters, who threw himself on a grenade to save the men around him, received the Navy Crossostumously. His action was not unique to Operation Swift. Similar sacrifices occurred throughout the war. Young men making instant decisions to trade their lives for the lives of their friends.

But each such sacrifice was unique to the man who made it. A choice that could not be taken back and that defined everything that followed. Peters died so that others might live. And those others would carry the weight of that gift for the rest of their days. The cormen who moved through the killing fields to treat the wounded displayed a courage that was almost incomprehensible.

These Navy medical personnel attached to marine units to provide battlefield care repeatedly exposed themselves to fire that had already killed and wounded so many. They treated wounds that would have made lesser men turn away. Working with hands that remained steady even when everything around them was chaos. Several cormen were killed during Operation Swift.

their bodies found among the men they had been trying to save. The officers and NCOs who held their units together during the worst of the fighting demonstrated leadership that no training could fully prepare a man to provide. They made decisions under fire, decisions that determined who would live and who would die. And they made them with incomplete information and inadequate time.

Some of these decisions were wrong, leading to casualties that might have been avoided. Others were right, saving lives that would have been lost without quick and correct action. The burden of these decisions would be carried by the men who made them for the rest of their lives. The individual riflemen and machine gunners and grenaders who held their positions under fire that should have driven any sane man to flight displayed a stubbornness that was the foundation of everything else.

They did not break. They did not run. They stayed in their holes and fought back against an enemy who outnumbered them and who had every advantage. Their courage was not the courage of action, but the courage of endurance. The refusal to quit that kept positions from being overrun and units from being destroyed. The pilots who flew the helicopters into hot landing zones, knowing that each approach might be their last, demonstrated a commitment to the men on the ground that went beyond professional obligation. They could have refused,

could have circled at safe altitude until conditions improved, could have prioritized their own survival over the survival of the wounded who needed evacuation. Instead, they flew into fire that had already brought down aircraft, landed in zones that were still under attack, and carried out men who would have died without their intervention.

The stories of heroism from Operation Swift were countless, most of them never recorded or recognized. The marine who carried a wounded friend through fire that should have killed them both. The squad leader who held his position long enough for his men to withdraw. The radio operator who continued calling for support even as he bled from wounds that would eventually kill him.

These stories were told among the men who had witnessed them passed down through the brotherhood of those who had been there. But they never became part of the official record. The medals that were awarded captured only a fraction of what had happened. The criteria for military decorations required specific verifiable acts that could be documented and witnessed.

But much of what happened in Operation Swift occurred in chaos that defied documentation, witnessed only by men who were themselves fighting for survival and who could not have written statements or provided testimony. The heroism that was recognized was the tip of an iceberg whose true dimensions could never be measured.

What the heroes of Operation Swift shared was not fearlessness, but the ability to act despite fear. They were all afraid, terrified in ways that would haunt many of them forever. But they did not let their fear control them. They did what needed to be done. Whether that meant throwing themselves on grenades or treating wounded under fire or simply holding a position that seemed impossible to hold.

Their fear was the context within which their courage became meaningful. The aftermath of Operation Swift extended far beyond the immediate clearing of the battlefield. The Marine Corps and the American military more broadly had to reckon with what had happened to understand how a routine sweep had turned into one of the bloodiest engagements of the war to extract lessons that might prevent similar disasters in the future.

The body counts were calculated and recalculated. The grim mathematics of attrition warfare producing numbers that were supposed to demonstrate progress. The Marines claimed hundreds of enemy dead, a toll that would have been devastating to the NVA force if accurate. But the claims were difficult to verify based on estimates and extrapolations rather than actual counts.

The enemy had been able to remove many of his dead during the withdrawal as he always did, leaving the Americans to guess at the true cost of the engagement. The afteraction reports that were produced in the weeks following the battle filled hundreds of pages with details that tried to capture what had happened. Unit movements were reconstructed from radio logs and survivor accounts.

Casualty figures were verified against medical records and graves registration reports. The tactical decisions that had been made were analyzed with the benefit of hindsight that had not been available to the men who made them. The most obvious lesson was about intelligence. The Marines who walked into the ambush on September 4th had not known what they were facing.

The intelligence that had prompted the operation had indicated enemy presence, but had grossly underestimated enemy strength and intentions. This was not unusual in Vietnam, where the enemy’s ability to conceal his dispositions regularly exceeded American ability to detect them. But the cost of this intelligence failure in Operation Swift was measured in over a hundred dead.

The tactical lessons were studied intensively. the enemy’s preparation of the battlefield, his use of interlocking fields of fire, his targeting of leaders and specialists, his willingness to close with American forces and accept the casualties that close combat entailed. All of these pointed to an adversary who was sophisticated and adaptable, the assumptions that American firepower would always be decisive, that the enemy would break under pressure, that technology would trump tactics.

All of these assumptions were challenged by what had happened. The questions about leadership were more difficult to address. Decisions had been made during Operation Swift that in retrospect had contributed to the disaster. Companies had been committed peacemeal, allowing the enemy to defeat them in detail. Reinforcements had been sent into the same traps that had snared the initial forces.

The opportunities to break contact and withdraw, to accept a tactical defeat rather than risk annihilation, had been rejected in favor of continuing attacks that only increase the casualties. But judging these decisions from the safety of hindsight was unfair to the men who had made them. The commanders in the Quaison Valley had not known what they were facing until it was too late.

They had acted on the information available to them, had made decisions that seemed reasonable in the moment, had tried to accomplish the mission while preserving the lives of their men. That they had failed in both objectives was not necessarily evidence of incompetence. It might simply have been evidence that the situation they faced was impossible.

The larger questions about the war itself were raised by Operation Swift, though they were rarely addressed directly. The attrition strategy that governed American operations in Vietnam assumed that killing enough enemy soldiers would eventually break their will to continue fighting. But the enemy in the Quaison Valley had demonstrated that he could inflict casualties on the Americans that were at least as damaging as those he received.

If attrition was a competition, it was not clear that America was winning. The human cost of Operation Swift was felt most acutely in the communities that had sent young men to Vietnam and would not see them return. The notifications arrived in the days and weeks following the battle. Uniformed officers appearing at doors across America to deliver news that would shatter families.

The funerals followed, ceremonies that tried to honor the dead while providing comfort to the living. Rituals that could never be adequate to the magnitude of the loss. The survivors returned to their units or to the hospitals or to the states, carrying memories that would never fade. Some would speak about what had happened, trying to convey experiences that defied ordinary language.

Others would remain silent, keeping their memories locked away where they would fester and grow and eventually demand attention that could no longer be deferred. The psychological casualties of Operation Swift would continue accumulating for decades. A toll that no afteraction report could capture. The war continued.

Operation Swift was followed by other operations, other battles, other casualties that added to the total that would eventually exceed 58,000 Americans killed. The Quaison Valley remained contested. The enemy returning to fight and die and kill in terrain that had already been soaked with blood. The lessons that might have been learned from Operation Swift were often not learned, or learned and then forgotten, or learned but impossible to apply given the constraints under which the war was being fought.

More than 50 years have it passed since Operation Swift, and the men who fought it are old now, if they are still alive. The young Marines who walked into the Quaon Valley in September 1967 are in their 70s and 80s. Their bodies marked by time and often by the wounds they received in that distant place. Their numbers diminish each year as age claims those whom the war could not.

And soon there will be no one left who can say from personal experience what Operation Swift was actually like. The 127 Marines who died during Operation Swift are remembered on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. their names etched into the black granite along with the names of all the others who did not come home.

The wall does not distinguish between operations, does not indicate which names belong to which battles, does not tell the stories that lie behind each inscription. The names are simply there, a roster of the dead that grows more distant from living memory with each passing year. The Quaison Valley itself has changed in the decades since the war.

The bunkers and trenches have been filled in or collapsed. The shell craters have been smoothed over by cultivation and erosion. The villages that were devastated have been rebuilt or abandoned. Their populations moved by war and peace and the ordinary processes of social change. A visitor today would see rice patties and mountains would feel the same heat and humidity that the Marines felt, but would find little physical evidence of what happened there in September 1967.

The farmers who work the fields today may not know what lies beneath the soil they cultivate. The bones of young men, American and Vietnamese, remain scattered through the valley, too deeply buried or too fragmented to be recovered. The metal from the weapons and equipment that was abandoned has long since rusted away or been collected for salvage.

The physical traces of Operation Swift have been absorbed by the Earth that witnessed it. But the memory remains preserved in the minds of those who were there and in the records they have left behind. The official afteraction reports sit in archives available to historians who want to understand the details of what happened.

The personal accounts, the memoirs and oral histories that survivors have provided offer perspectives that the official records cannot capture. Together, these sources preserve a version of Operation Swift that future generations can study and try to understand. But understanding Operation Swift requires more than studying documents.

It requires imagination. The willingness to place yourself in the position of young men who walked into a trap and fought their way out or did not fight their way out, who experienced violence of such intensity that it marked them forever. It requires empathy, the recognition that these were real people with real hopes and fears, not abstractions or statistics or characters in a story.

It requires humility. The acknowledgement that those of us who were not there can never fully comprehend what it was like for those who were. The lessons of Operation Swift are not primarily military lessons. Though military lessons can certainly be extracted. The lessons are about what war does to the people who fight it.

About the costs that are paid, not just in bodies, but in minds and spirits. about the gap between the abstractions of policy and strategy and the reality of young men killing and dying in a valley on the other side of the world. These lessons are not new. They have been taught by every war in human history. But each generation seems to need to learn them again.

The men who fought Operation Swift deserve to be remembered. Not because what they did was glorious, but because what they did was hard. They went where they were sent. They fought when they were told to fight. They died, many of them, in a cause whose justification became increasingly unclear even as they served it. Their sacrifice was real, regardless of whether it was wise.

Their courage was genuine, regardless of whether it was well employed. They were ordinary young Americans who were asked to do extraordinary things. And many of them rose to the occasion in ways that honor demands we acknowledge. Operation Swift was four days in the Quaison Valley. A battle that began with an ambush and ended with a withdrawal that killed 127 Marines and wounded hundreds more that demonstrated both the determination of the enemy and the courage of the Americans who faced him.

It was one battle among many, one tragedy among thousands, one story among the countless stories that together constitute the American experience in Vietnam. But it was also unique. a specific set of events that happened to specific people at a specific time and place that deserves to be remembered in its particularity as well as its generality.

The survivors of Operation Swift, those who are still alive to remember, carry their memories into the final years of their lives. Soon they will be gone, and Operation Swift will exist only in the historical record, in books and documents and accounts like this one. Before that happens, their stories deserve to be told.

The world should know what happened in the Quaison Valley in September 1967. The world should know what those young men did and what was done to them. This is the story of Operation Swift. This is the story of 127 Marines who did not come home. This is the story of the Valley of Death. The names of the dead are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial panels 26E through 27E.

Rows of names that represent rows of graves, rows of families that were shattered, rows of futures that were never realized. Those names are not just names. They were sons and brothers and husbands and fathers. They were young men who answered their country’s call and paid the price that their country demanded.

The survivors who visit the wall to find those names often trace them with their fingers, a gesture of connection. Across the years, a way of touching friends who died more than half a century ago. They stand before the black granite and remember and the memories are as vivid now as they were then. Und dimmed by time, unddeinished by distance.

They remember the heat and the fear and the noise and the death. They remember Operation Swift. The wall does not explain what happened to the men whose names it bears. It does not describe the battles they fought or the manner of their deaths. It simply records their names, a testament to their sacrifice and a challenge to those who come after to remember what that sacrifice cost.

The names are silent, but they speak to those who know how to listen. May they never be forgotten.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.