Dark Things the Viet Cong Did to Captured M60 Gunners

November 17th, 1965. 10:30 hours. The Ia drang valley. The air is not just hot. It is solid. It tastes of cordite and wet rot. Private first class Toby Brave Boy is hugging the dirt behind a termite mound that feels as hard as concrete. In his hands is 23 lbs of cold rolled steel and stamped metal, the M60 machine gun.

The pig. For the last 20 minutes, he has been the god of this small patch of jungle. Every time he squeezes the trigger, a line of orange tracers rips through the elephant grass at 2,800 ft per second. He controls the space. He dictates who lives and who dies in the 1100 m ahead of him. The power is intoxicating. It rattles his teeth.

It vibrates in the marrow of his bones. But then the belt runs dry for 6 seconds. While his assistant, Gunnner, fumbles with the feed tray cover. The god becomes immortal. The noise stops. And in that silence, a terrifying realization washes over him. The enemy was not suppressed. They were waiting. They were counting.

A whistle blows from the treeine. It is not a signal to retreat. It is a signal to advance. They are not charging the riflemen on the left. They are not charging the command post in the rear. Three North Vietnamese regulars rise from the grass less than 30 m away. Their eyes are fixed on one thing, not the radio, not the officer.

They are looking at the machine gun. The logic of the battlefield has inverted. The weapon that made him the most powerful man in the platoon has instantly made him the most vulnerable. He is no longer the hunter. He is the prize. Statistics from the Department of Defense would later suggest that in a high-intensity firefight during the Vietnam War, the average life expectancy of an exposed machine gunner was measured in seconds, not minutes.

But death was the simple outcome. Death was the clean break. There was a third option, one that haunted the barracks conversations from Daang to the Meong Delta. It was the option where the gun jams. The option where the perimeter collapses. The option where the gunner does not die, but wakes up with his hands bound with communication wire, staring into the eyes of men who have spent three years learning exactly how to dismantle him.

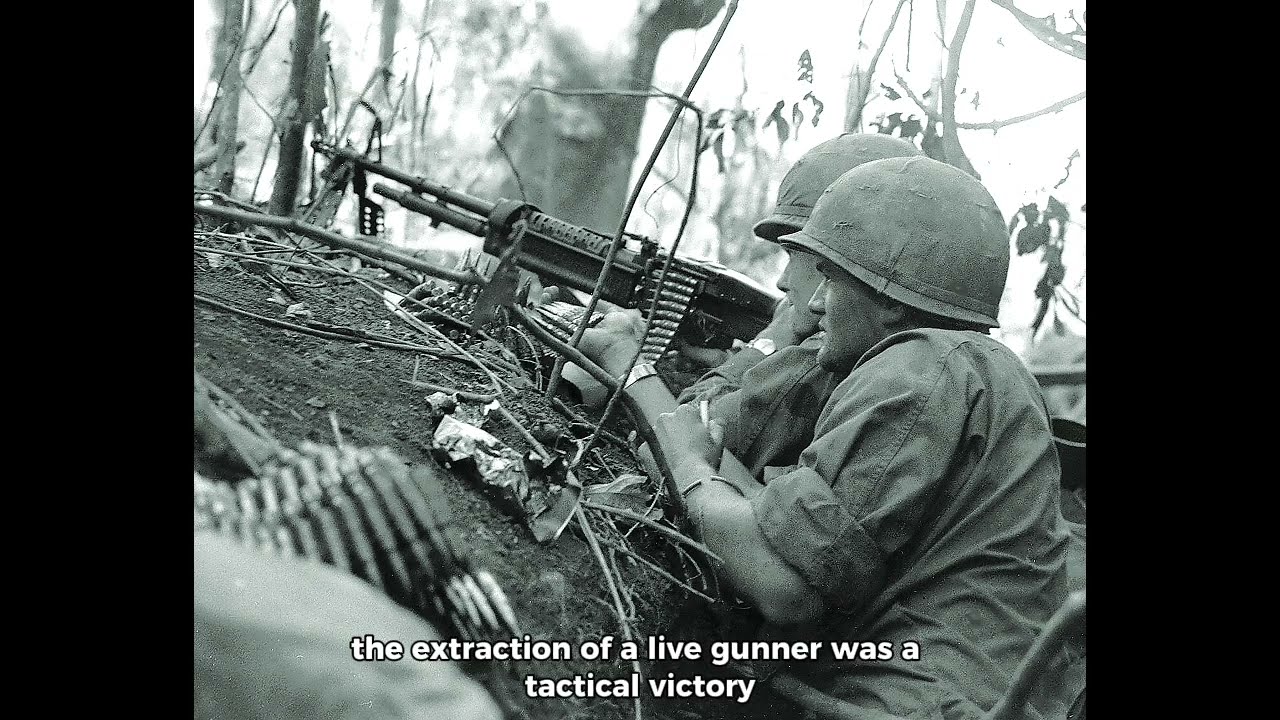

This is the story of the men who carried the heaviest burden. This is the story of what happened when the heavy end of the firepower equation fell into the hands of the enemy. To understand the fate of the captured gunner, you must first understand the machine. The M60 generalpurpose machine gun was the backbone of American infantry tactics. It fired the 7.

62 mm NATO round. It cycled at 550 rounds per minute. It was designed to bridge the gap between the automatic rifle and the heavy caliber Browning. In the doctrine of the United States Army, the M60 was the base of fire. When a squad made contact, the riflemen were there to protect the gun. The gun was there to kill the enemy. It was the anchor.

If the gun moved, the line moved. If the gun fell, the line broke. This doctrine was not a secret. The National Liberation Front, known to the Americans as the Vietkong and the People’s Army of Vietnam, the NVA, studied American field manuals with the same intensity as the men at Fort Benning. They knew the weight of the gun.

They knew the cyclic rate. They knew that the barrel had to be changed after 2 minutes of sustained fire or the rifling would melt. Most importantly, they knew the psychological hierarchy of the American platoon. They knew that the soldiers rallied around the noise of the pig. The rhythmic thumping of the M60 was the heartbeat of the unit.

As long as they heard it, they knew they were still in the fight. Therefore, the North Vietnamese doctrine was cold and specific. Silence the gun and you kill the morale. Capture the gunner and you break the spirit. The men who carried the M60 were often the biggest men in the platoon. They had to be. The gun alone weighed 23 lbs.

A belt of 100 rounds weighed another seven. A typical loadout for a patrol in the central highlands might involve the gunner carrying the weapon and 600 rounds of ammunition. He was carrying nearly 60 lb of killing power before he even strapped on his water, his rations, or his flack jacket. This physical reality created a specific mindset.

The machine gunner was a laborer. While the rifleman could move with relative agility, the gunner was a beast of burden. He walked slower. He sweated more. He developed a fatalistic bond with the weapon. He cleaned it before he cleaned his own body. He oiled it before he ate. He slept with it curled against his chest like a child.

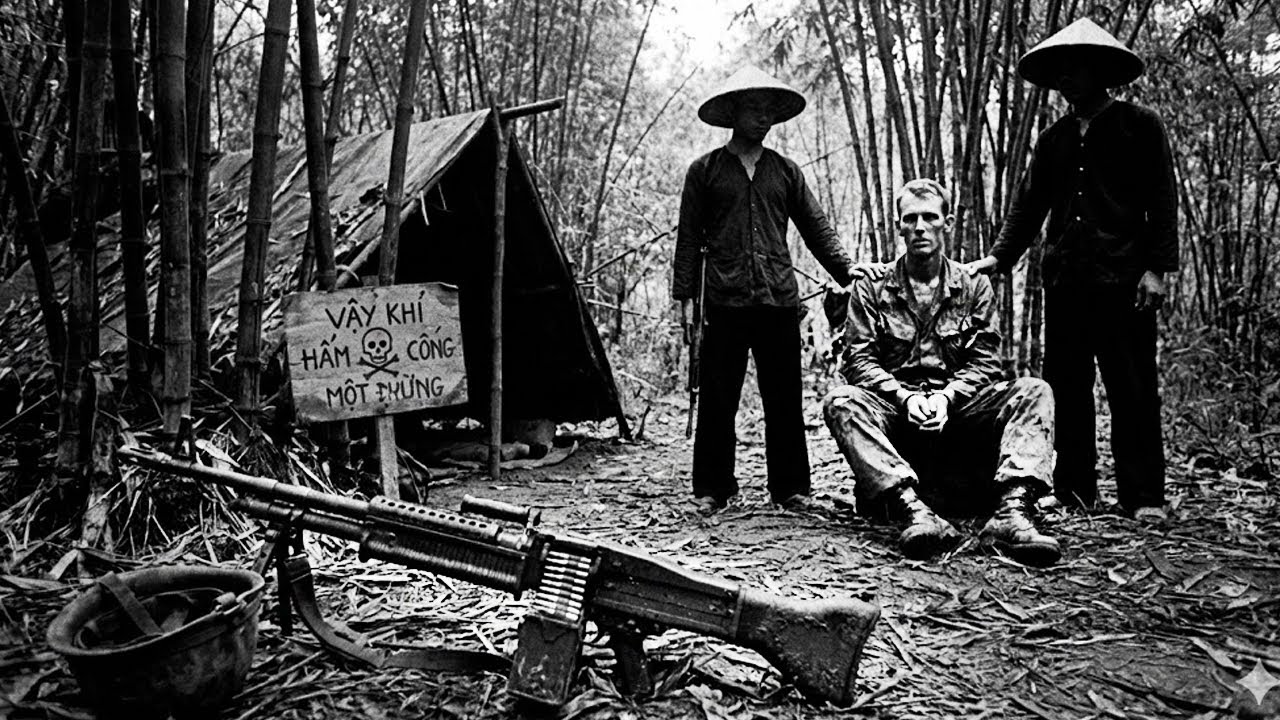

This bond is critical to understanding what came next. When a rifleman is captured, he is disarmed. When a machine gunner is captured, he is severed. He is stripped of the object that defined his existence and his survival. The capture of an M60 gunner was rarely an accident of chaos. It was often the result of a deliberate coordinated effort by specialized Vietkong hunter killer teams.

By 1967, intelligence reports from the first infantry division operating in the Iron Triangle began to notice a disturbing pattern. In ambushes, the initial volley of rocket propelled grenades, the RPG7s, was not directed at the lead element or the radio operator. It was directed at the machine gun teams.

The Vietkong had learned to identify the gunner even before the shooting started. They looked for the silhouette, the way the man hunched under the weight, the distinctive shape of the spare barrel bag carried by the assistant. They looked for the asbestous mitten hanging from the gunner’s web gear used to handle the searing hot barrel during changes.

Once the ambush was initiated, the objective shifted. If the gunner was killed, the VC would risk mass casualties to retrieve the weapon. But if the gunner was merely wounded or concussed by the blast, the dynamic became far darker. There are accounts from the Asha Valley of NVA regulars bypassing wounded riflemen to swarm a stunned machine gunner.

They did not shoot him. They dragged him. The extraction of a live gunner was a tactical victory that resonated far beyond the immediate skirmish. It was a propaganda coup. It was an intelligence gold mine and it was a source of labor. The transition from combatant to prisoner usually began with a blur of violence that shocked the system into a state of dissociation.

Imagine the sensory experience. One moment, you are deafened by the roar of your own weapon, the adrenaline masking the fatigue of a 6-hour patrol. The next, a concussive blast knocks the world sideways. The air is sucked out of your lungs. You reach for the pistol grip of the M60, but your hand grasps only mud. Then comes the smell.

The distinct fermented smell of fish sauce and unwashed bodies that American soldiers often associated with the close proximity of the enemy. Hands are on you. Not the frantic checking hands of a medic, but rough tearing hands. The first thing they take is the boots. This was standard procedure for all prisoners, but for a machine gunner, it was the first step in a calculated process of immobilization.

A gunner is accustomed to a solid stance. He plants his feet to ride the recoil. By taking his boots, they sever his connection to the ground. The jungle floor is a carpet of thorns, bamboo spikes, and biting insects. Without boots, the American giant is reduced to a hobbling invalid within hours. Next, they strip the webbing, the canteen, the rations, the entrenching tool.

They leave the uniform usually, but they strip the identity. But for the gunner, there is often a special attention paid to the hands. The hands that fed the belt, the hands that changed the barrel. Survivors from camps in the Yuman Forest recall that captured gunners were frequently bound differently than other prisoners.

While riflemen might have their elbows tied behind their backs, gunners often had their thumbs wired together with copper wire, pulled tight until the circulation cut off. This was not just cruelty. It was pragmatism mixed with symbolism. Those hands had killed their comrades. Those hands were the mechanism of the machine. By crushing the hands, they neutralize the threat permanently.

The initial march is where the reality of the new existence sets in. The captured gunner is often forced to carry the very weapon he used against his capttors. This is a psychological master stroke by the Vietkong. The gun, once his protector, becomes his tormentor. He is forced to carry the pig, but without the sling. He must cradle 23 lbs of dead weight in his arms, his thumbs throbbing against the wire bindings.

If he stumbles, he is beaten with bamboo canes. If he drops the weapon, he is denied water. They walk for days. The Vietkong logistics system was a marvel of human endurance. Moving through terrain that Americans considered impassible. They moved at a trot, a relentless pace that wore down the larger, heavier American frames. A machine gunner, often chosen for his size and strength, requires more calories and more water than a smaller man.

The deprivation hits him harder and faster. The muscle mass that allowed him to hump the gun through the patties begins to consume itself. The destination is not a prison in the conventional sense. There are no stone walls or iron bars. The prison is the jungle itself. It is a bamboo cage sunk into the earth or a clearing under the triple canopy where the sun never quite touches the ground.

Here the gunner is introduced to the hierarchy of the camp. And here he discovers that his specialty has earned him a special place in the interrogation rotation. The Vietkong intelligence officers were not interested in the grand strategy of the war. They did not ask about the movements of carriers in the South China Sea or the political decisions in Washington. They wanted tactical data.

And the machine gunner knew the things they needed to know. He knew the interlocking fields of fire. He knew the sector stakes. He knew how the claymores were set up in front of the gunpits. He knew the resupply cycles for ammunition. To extract this information, the captors utilized a mixture of physical torture and environmental weaponization.

One documented technique involved the cage of silence. The prisoner would be placed in a bamboo tiger cage too small to stand up in, too short to lie down in. He was forced to crouch. For a man with the heavy build of a gunner, the cramping was immediate and agonizing. But the physical pain was secondary to the isolation.

They would leave him there. No questions, no beatings, just the jungle. The mosquitoes would descend in clouds. The leeches would crawl up through the slats in the bamboo floor. The dysentery would set in. After 3 days of this, a political officer would arrive. He would offer water. He would offer a cigarette.

He would speak in soft, perfect English. He would ask about the gun. “The M60 is an unreliable weapon, is it not?” he might say. It jams in the dust. It is heavy. Your officers make you carry it because they do not care about your back. They ride in helicopters. You walk in the mud. This was the wedge. They tried to exploit the resentment that every infantryman feels towards the brass, but they tailored it to the specific misery of the machine gunner.

They tried to turn the soldier against his own role. If the soft approach failed, the dark things truly began. There are accounts of gunners being tied to trees near Antills. The sugar from their own rations would be rubbed on their exposed skin. It is a slow, maddening torture that leaves no broken bones, but shatters the mind.

There were worse things. The rope trick, as it was grimly known by PS, released in 1973 during Operation Homecoming. This involved binding the arms behind the back and hoisting the prisoner off the ground by his wrists. For a large man, the weight of his own body would dislocate the shoulders within minutes. The pain is absolute. It blinds the vision.

But the physical torture was often just the prelude to the labor. The Vietkong operated on a philosophy of total utilization. A prisoner who could not provide intelligence could still provide work. And a machine gunner, even emaciated, was seen as a source of raw power. In the camps along the Cambodian border, prisoners were used as pack animals to move supplies down the Ho Chi Min Trail.

They were loaded with sacks of rice or boxes of ammunition. The irony was cruel. The gunner who had once carried the ammunition to kill these men was now carrying the ammunition that would be used to kill his friends. He would be forced to walk barefoot over sharp carsted limestone. The infections would set in quickly. Jungle rot, a fungal infection that eats away the skin, would turn feet into raw, weeping meat. Yet, they were kept alive.

Why? Because a dead American was of no value. A living American was a bargaining chip. He was a symbol of the enemy’s weakness. The Vietkong propaganda machine loved to film captured airmen, the pilots who fell from the sky. But for the domestic audience, for the morale of the guerilla fighter in the tunnel, the sight of a captured infantry man, specifically a heavy weapons specialist, was more visceral.

It proved that the American giant could be brought down to the mud. Let us zoom in on a specific sector. The year is 1968. The location is the Asia Valley. This was Indian country, a place where the NVA had built a road network under the canopy. We focus on a man we will call Sergeant Miller. Miller was a career soldier, a grid coordinate of a man who ran a weapons squad.

He was captured in May during a botched extraction. Miller was not just a gunner. He was a teacher of gunners. He knew the M60 better than the men who designed it. When he was captured, the NVA commander realized who he was. They did not put Miller in a cage immediately. They took him to a clearing where a captured M60 sat on a stump. It was rusted.

The gas piston was seized. The bolt was frozen. They threw Miller’s boots into the jungle and pointed at the gun. “Fix,” the officer said. Miller refused. He was beaten with rifle butts until his ribs cracked. He still refused. They tied him to a bamboo stake in the center of the clearing and left him in the sun for two days without water.

When they cut him down, he could barely stand. They dragged him back to the gun. Fix. Miller looked at the weapon. It was his religion. Seeing it in that state, rusted and useless, triggered something deep in his lizard brain. It was a perverse instinct. He wanted to fix it. Not for them, but for the gun. He disassembled it.

His hands, shaking and swollen, moved with a memory that bypassed his conscious thought. He cleaned the gas cylinder with a piece of rag. He oiled the bolt with pig fat they provided. He reassembled it. The metallic clack of the bolt going home was the loudest sound in the valley. The NVA officer smiled. He had broken the soldier by using the soldier’s own competence against him.

Miller was then forced to conduct classes. He had to show young NVA conscripts how to clear a jam, how to change a barrel. This is the psychological dark side that is rarely discussed. The forced collaboration, the manipulation of professional pride. Miller was not betraying his country in his own mind.

He was servicing a weapon, but in doing so, he was making the enemy more lethal. The guilt of this action is a weight heavier than the gun itself. Survivors speak of the gray zone of captivity. It is not a movie where you name, rank, and serial number until you die. It is a series of impossible choices made in a state of starvation and delirium.

The Vietkong knew that a machine gunner felt responsible for the safety of his platoon. They used this during interrogations. They would not threaten the gunner. They would threaten the other prisoners. If you do not tell us the radio frequency, they would say, we will stop feeding the boy with the leg wound. The boy was usually a rifleman from the same unit.

The gunner conditioned to be the protector, the base of fire, the big brother would crumble. He could take the pain himself, but he could not watch his a gunner rot to death. This leverage was systematic. It was a dark inversion of the band of brothers ethos. The bonds that made the unit strong in combat were the same bonds that the enemy used to dismantle them in captivity.

But there is another layer to this darkness. It is the medical reality of the captured gunner. The M60 gunner often suffered from specific occupational injuries even before capture. Hearing loss was universal. The gun operated at 150 dB. Many gunners were partially deaf. In the whispering environment of the jungle prison, this was a terrifying disability.

They could not hear the guard approaching. They could not hear the signal to bow. They were beaten for disobedience. They did not hear. Also, the back problems, the compression of the spine from carrying the heavy loads in the bamboo cages where they could not stand up. These injuries flared into crippling spasms. A gunner who could not work was a liability.

The Vietkong had a solution for liabilities. They did not have the medicine to treat them, and they did not have the food to waste on them. The release program was often a cynical exercise. When a prisoner became too sick to work or too broken to interrogate, the VC might release him to an American patrol or a village. This was not an act of mercy.

It was an act of logistics. They were offloading a mouth they didn’t want to feed. But for the gunner, the journey to that point of release was a descent into a primal state. Let’s look at the numbers. Statistics from the era are difficult to parse because the North Vietnamese did not keep centralized records of every prisoner in the South and many men were simply listed as missing in action.

However, postwar analysis of returning PS shows a disparity. Pilots captured in the north had a survival rate that while grim was higher than the infantry captured in the south. The pilots were valuable political pawns kept in Hanoi. The grunts captured in the jungle were kept in the jungle.

For the enlisted machine gunner, the survival rate was terrifyingly low. The combination of the initial targeting, the physical demands of their body type versus the starvation diet, and the specific animosity directed toward heavy weapons crews created a lethal funnel. In the camps, the hierarchy of suffering was flattened, but the experience of the gunner retained a specific flavor of tragedy.

He was the man who had commanded the most attention on the battlefield, the man who had been the loudest. Now he was required to be the quietest. To survive, the gunner had to shrink. He had to shed the identity of the pigman. He had to become small, invisible. For a man who had built his identity on being the anchor of the platoon, this psychological amputation was as painful as the physical torture.

November 1969, a camp near the Cambodian border. A group of five Americans is huddled in a pit. The monsoon rain has turned the floor into a slurry of mud and excrement. Among them is a specialist fourth class, a machine gunner from the 25th Infantry Division. He has been there for 6 months. He has lost 60 lbs.

His skin is a map of fungal infections and insect bites. He is hallucinating in his delirium. He is not in the pit. He is back on the burm at fire support base. He is holding the M60. He can feel the vibration. He is calling out for ammo. Ammo up. The guard standing at the lip of the pit hears the shouting.

He does not see a soldier reliving a battle. He sees a noisy prisoner for breaking the rules of silence. The guard drops a bamboo grenade, a hollowedout section of stalk filled with black powder and scrap metal into the pit. It is a cruel, low-grade explosive. It is not enough to kill everyone, but it is enough to punish.

The explosion in the confined space is deafening. Shrapnel bites into emaciated flesh. The gunner screams. The scream is the only weapon he has left. This is the reality of the captured gunner. It is not a single event of capture. It is a long slow erosion of humanity. It is the systematic dismantling of a soldier piece by piece until only the raw nerve endings remain.

But to truly understand the depth of this darkness, we must look at what happened when the system worked. When the interrogation broke the man, when the labor broke the body, what was left? There were instances where American patrols would find a marker on the trail, a warning. Sometimes it was just a boot, an American jungle boot, size 12 wide, the size of a big man, placed on a stick in the middle of the path. Sometimes it was worse.

In the summer of 1967, a longrange reconnaissance patrol LRP team moving through zone D found a body tied to a tree. It was an American. He had been dead for days. He was missing his hands. And around his neck, hung by a piece of communications wire, was the feed tray cover of an M60 machine gun. The message was clear.

It was not written in words, but in the brutal language of guerilla warfare. This is what happens to the men who bring the fire. This is the price of the pig. The darkness was not just in what they did to the bodies. It was in the message they sent to the living. Every gunner who saw that or heard the story about it back at the base camp felt the weight of his weapon increase.

The M60 was no longer just a tool. It was a curse. This psychological warfare was effective. It created a hesitancy, a split second of doubt. If I open up with this gun, I am marking myself. If I get left behind, that is my future. And in a firefight, a split second is the difference between life and death.

The Vietkong understood this leverage perfectly. They didn’t just want to capture a man. They wanted to capture the mind of every man who was still free. They wanted the gunner to be afraid of his own gun. This fear was a constant passenger. It sat on the shoulder of every man who carried the pig.

It was there when they cleaned the barrel. It was there when they loaded the belt. It was there when they walked point. And it is this fear that makes the story of the captured gunners so necessary to tell. Because despite the horror, despite the torture, despite the statistical probability of death, they picked up the gun.

Day after day, patrol after patrol, they strapped on the 23 lbs of steel. They wrapped the belts of ammo around their chests and they walked into the green dark knowing exactly what was waiting for them if they fell. January 20th, 1969. Deep in war zone C northwest of Saigon, the jungle canopy is so thick that noon looks like twilight.

Here, the concept of a prisoner of war camp is a misnomer. There are no guard towers. There are no spotlights. The prison is a series of bamboo cages sunk 3 feet into the mud, camouflaged with palm frrons. Inside one of these cages, which measures 4 ft high by 3 ft wide, sits a man we will call Corporal Jackson.

Before his capture, Jackson was 6’2. He was a slab of muscle who could shoulder fire the M60 while walking. Now he is a folded geometric shape of bone and skin. He cannot stand. He cannot lie flat. He exists in a permanent trembling crouch. This is the tiger cage. It was the primary instrument of behavioral modification used by the Vietkong against uncooperative elements.

For a machine gunner, the cage was not just confinement. It was a specific anatomical torture. The physiology of a heavy weapons operator is built on core strength and leverage. By forcing a large man into a box designed for a much smaller frame, the captors initiated a process of rapid muscular atrophy. The cramps began within hours.

The screaming usually started on the second day. By the fourth day, the screaming stopped, replaced by a low, rhythmic moaning as the leg muscles seized and began to tear away from the bone. But the physical degradation was merely the softening up phase. The true darkness lay in the re-education curriculum that followed.

The Vietkong viewed the M60 gunner not just as a soldier, but as a technician of imperialist aggression. In their Marxist Leninist framework, the rifleman was a conscript to be pied, but the machine gunner was a specialist to be broken. He controlled the means of destruction. Therefore, his confession had to be total.

The interrogation sessions were often conducted by a cadre leader who spoke colloquial English learned perhaps in Hanoi or from previous prisoners. They did not begin with torture. They began with a lesson in economics. You carry the heavy gun, the interrogator would say, offering a cup of tea that the prisoner was too terrified to drink.

Does the son of the banker carry the heavy gun? Does the son of the senator carry the ammo? No, they are in college. You are here. You are the worker. The M60 is your shovel and you are digging your own grave. This was a psychological scalpel. It cut deep because for many drafties it contained a grain of truth. The Vietkong doctrine was to weaponize the American class system against the American soldier.

They knew that the M60 gunner often came from the working class, mechanics, farm hands, construction workers, men used to physical labor. They would show the gunner photographs not of battles, but of anti-war protests in Chicago and Washington. See, they would point, “Your own people spit on you. We are the only ones who respect you.

We respect your strength, but you use it for the wrong side. If the gunner resisted this narrative, the tone shifted. The politics of rice was enacted. The human body in a high stress jungle environment requires approximately 3500 to 4500 calories a day to maintain mass. A captured American was typically fed a ration of roughly 400 to 600 calories.

Usually, this was a ball of rice, perhaps tainted with sand, and a sliver of dried fish or manio root. For a 140lb rifleman, this diet is slow starvation. For a 200lb machine gunner, it is a metabolic catastrophe. The body, denied fuel, begins to cannibalize itself with terrifying speed. It burns fat first, then muscle, then organ tissue.

The Vietkong controlled the food with absolute precision. They would place a bowl of fish sauce and extra rice just outside the cage of the gunner, just out of reach. Sign the declaration, they would say. Admit that you used your machine gun to murder civilians. Admit that the M60 is a terror weapon. Then you eat.

The declaration was a pre-written statement. It usually contains specific technical details about the lethality of the weapon. Details that only a gunner would know, lending the propaganda authenticity. I fired into the thatched roofs. I saw the tracers ignite the schoolhouse. This was the moral trap. to eat. To survive, the gunner had to agree to become a war criminal on paper.

He had to desecrate his own service. Those who signed often broke mentally. The act of signing was a surrender of identity deeper than the surrender of the weapon. Those who refused were introduced to the hole. This was a pit dug vertically into the ground, barely wide enough for a man’s shoulders. The prisoner was lowered in and a great was placed over the top.

Darkness was absolute. Ventilation was poor. In the wet season, the water level would rise to the prisoner’s neck. He would have to stand on his tiptoes for hours, days, to keep his nose above the filth. It was in these holes that the specific nightmare of the machine gunner often came full circle.

Deprived of sensory input, the mind loops. Survivors recount hallucinating the sound of their gun. The thump, thump, thump of the M60 became the rhythm of their heartbeat. They would mime the actions of clearing a jam in the dark. Their fingers working invisible bolts trying to fix a malfunction that didn’t exist.

But the Vietkong did not just want broken men. They wanted useful ones. And this leads to one of the darkest chapters of the P experience, the logistics of betrayal. As the war dragged on into the late60s, the NVA supply lines were stretched thin. They needed every able-bodied person to move material. The lenient treatment policy was a facade for slave labor.

Captured gunners, despite their emaciation, were often selected for the heavy lift gangs. They were forced to hump mortar rounds and bags of rice down the precipitous trails of the anomite range. Consider the cruelty of the physics. A man who once carried a 60 lb combat load to protect his friends is now carrying a 60 lb load of enemy ordinance to kill them.

If a prisoner collapsed, the guards used a technique known as the prod. They sharpened bamboo sticks and jabbed them into the lower back or the buttocks. It wasn’t a deep wound, but it was constant, a thousand jabs a day. The skin would become a mass of infected punctures. During these forced marches, the gunners were often made to walk past American bomb craters.

The guards would stop the column. They would force the prisoners to look at the devastation. This is your work, they would say. This is what your machine does. It was a relentless 360deree assault on the prisoner’s psyche. They were not allowed to be victims. They were forced to be perpetrators who were finally being punished.

There is a documented instance from a camp near the Cambodian border involving a captured gunner from the fourth infantry division. Let’s call him Specialist Roberts. Roberts had resisted the indoctrination. He had refused to sign the leaflets. He had survived the cage in the hole. So the camp commander tried a different approach.

He didn’t want a confession. He wanted a consultant. The camp had captured a significant cache of American weapons from a convoy ambush. Several M60s, M16s, and crates of ammunition. But the M60s were finicky. They were jamming. The Vietkong guerrillas, used to the loose tolerances of the AK-47, could not master the gas system of the American gun.

They dragged Roberts out of his pit. They set up a table. On it lay the pieces of three M60 machine guns. Assemble one working gun, the commander said. If you do this, you get medicine for your feet. If you do not, we will shoot the man next to you. The man next to him was a 19-year-old radio operator who was shivering with malaria.

Roberts stood over the metal. This is the gray zone of survival. The ethical binary of right and wrong dissolves when you are staring at the trembling back of a dying friend. Roberts went to work. His hands covered in jungle ulcers moved over the sear and the operating rod. He knew the trick to wiring the gas cylinder so it wouldn’t vibrate loose.

A trick not in the manuals. a trick only a grunt knows. He performed the maintenance. He built a weapon that would fire. The commander was pleased. He picked up the gun. He walked to the edge of the clearing and fired a burst into the trees. The gun ran perfectly. The orange tracers cut a clean line through the leaves.

The sound of that American gun firing in the hands of the enemy fixed by American hands is a sound that Roberts would hear every night for the rest of his life. He saved the radio operator that day, but the cost was a piece of his soul. This specific type of technical exploitation was more common than admitted. The Vietkong respected the M60s firepower, even if they hated its weight.

They used captured American gunners to train their own heavy weapons teams on how to counter it. Where is the blind spot? They would ask. How long does it take to change the barrel? When the gunner is reloading, where does the assistant look? They were mining the prisoner’s professional expertise to kill his replacements.

And then there were the medical experiments, not the sterile clinical experiments of a laboratory, but the crude opportunistic surgery of the bush. The NVA field hospitals were desperate for blood and practice. Captured Americans sometimes served as living blood banks. A large machine gunner was seen as a reservoir. They would drain a pint, two pints to transfuse into a wounded NVA officer.

There are unverified but persistent accounts of American prisoners being used for surgical practice. Trainy medics learning to amputate limbs or suture arteries on imperialist aggressors before working on their own comrades. The logic was utilitarian and brutal. If the prisoner died, it was one less mouth to feed.

If he lived, he had served the revolution. But perhaps the most insidious dark thing was the manipulation of release. Occasionally, the Vietkong would release a prisoner. It was usually done for propaganda purposes, time to coincide with a visit from an anti-war delegation or a holiday. Who got released? It was rarely the hardliners.

It was rarely the strongest. It was often the man who had been most thoroughly broken or the man who was so physically destroyed that his appearance would shock the American public. But before release, there was a final ceremony, the farewell. The prisoner would be cleaned up, given a fresh set of black pajamas, fed a meal with meat.

The camp commander would sit with him like an old friend. You are going home, the commander would say. We are merciful. We forgive you. But remember, you are alive because we allowed it. Your government sent you here to die. We gave you life. They would hand him a souvenir. Sometimes a comb made from the wreckage of an American plane.

Sometimes a ring made of aluminum. Take this. When you look at it, remember who holds the power. For a machine gunner returning to the world after this was a dislocation of reality. He would be flown to a hospital in the Philippines or Japan. He would be surrounded by clean sheets, endless food, nurses. But he would look at his hands, the hands that had fixed the gun for the enemy, and he would feel the copper wire still cutting into his thumbs.

He would hear a car backfire and freeze, waiting for the bamboo grenade. The dark things did not stay in the jungle. They traveled home. One of the most chilling aspects of the post capture trauma for these men was the inability to explain the specific nature of their guilt. How do you explain to a civilian or even to a regular soldier what it feels like to trade the operational secrets of your weapon for a bowl of rice? How do you explain the politics of rice? The Department of Defense debriefings were exhaustive. They wanted to know about

codes, escape routes, camp locations. They were less equipped to handle the confession of a man who said, “I showed them how to clear the feed tray because I didn’t want to die.” The military code of conduct says, “I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country.” It is a black and white standard written in a warm room.

In the Tiger Cage, the standard is gray. Let’s look at the numbers again to understand the scale of this attrition. In some operational areas, the return rate for captured enlisted infantry was less than 50%. The jungle simply ate them. But those who did not return often suffered fates that were only discovered years later.

In 1970, after the invasion of Cambodia, American forces discovered a series of hasty graves near a hastily abandoned hospital complex. The forensic analysis of the remains told a story that no script could invent. They found bodies with their hands tied, but they also found bodies with specific healed fractures in the feet.

the Bastonado torture where the soles of the feet are beaten. They found skulls with the orbital bones crushed, the signature of rifle butt strokes. And in one grave, they found a skeleton wearing a rusted dog tag. Entangled in the rib cage buried with him was the heavy rusted bolt assembly of an M60 machine gun. It was a final insult, a final marker.

The Vietkong had buried the man with his burden. Even in death, they would not let him put it down. This discovery reinforced the grim reality. The relationship between the gunner and his capttors was personal. It was intimate. It was a hatred born of respect for the damage the man could inflict, twisted into a desire to see that man reduced to zero.

As we move toward the climax of this story, we must understand that the darkness was not static. It evolved. As the war turned against the Americans, as the B-52 strikes shattered the sanctuaries, the treatment of prisoners in the jungle camps became more desperate and more feral. The lenient policy evaporated.

The cages got smaller. The rations got smaller. The graves got shallower. And for the M60 gunner, the man who represented the technological superiority of the United States, the end was often a stark demonstration of that superiority failing. He was the giant brought low by the ant. He was the thunder silenced by the silence of the bamboo.

February 12th, 1973. Clark Air Base, the Philippines. 1300 hours. A C141 Starlifter touches down on the tarmac. The engines wind down. The rear ramp lowers. The world is watching. The cameras are rolling. Operation Homecoming has begun. Out of the belly of the aircraft walk the men who have been ghosts for years.

They are wearing crisp new dress uniforms. They are clean shaven. They salute the flag. But look closer. Among the pilots who stride down the ramp with their heads held high, there are others. Men who have to be supported by nurses. Men who are squinting in the sunlight, their eyes darting toward the perimeter fence. Men who are 25 years old but walk with the shuffling gate of octogenarians.

These are the jungle prisoners, the grunts, the machine gunners. While the pilots in the Hanoi Hilton were organized, maintaining a military structure within the walls of the prison, the men in the jungle camps existed in a feral atomization. They had been kept in cages the size of coffins. They had been marched until their feet were black stumps.

This is the climax of their war, but it is not an end. It is a terrifying transition. For the machine gunner, the return to civilization is a sensory assault that rivals the initial combat. The messaul at Clark Air Base offers them a steak. A thick, juicy American steak. Sergeant Miller, the man who was forced to fix guns for the NVA, sits in front of the plate.

He holds the knife and fork, his hands permanently clawed from the copper wire bindings, cannot grip the utensils properly. He stares at the meat. He does not see food. He sees the politics of rice. He sees the bowl of fish sauce placed just out of reach. He begins to weep. Not a sob of relief, but a silent shaking convulsion. He pushes the plate away.

He hides a bread roll in his pocket. He is safe, but his brain is still in the tiger cage. This is the final dark victory of the Vietkong system. They did not just break the body. They rewired the survival instinct. The medical intake exams reveal the forensic truth of their captivity. The doctors find things that are not in the textbooks.

They find jungle rot that has penetrated to the bone, requiring amputation years after the infection started. They find intestinal parasites that have consumed 40% of the patients body weight. But for the gunners, they find the occupational scars, the spinal compression fractures from the beatings while carrying heavy loads, the nerve damage in the thumbs, the hearing loss that isolates them in a bubble of tinitus.

The climax of this story is not a parade. It is a diagnosis. The turning point comes when the euphoria of release fades and the gray zone follows them home. The Department of Defense intelligence officers begin the debriefings. They are looking for tactical data. Where was the camp? Who was the commander? What codes did you use? But then comes the question that every gunner dreads.

Did you cooperate? It is a binary question for a non-binary reality. How does Miller answer? Yes, I fixed their guns. Yes, I signed the paper. Yes, I carried the ammo. He sits in a white room with a tape recorder and a major from the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. He has to confess to his own survival.

The fear of court marshal hangs over these men. The code of conduct was absolute. I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country. But the code did not account for the bamboo grenade in the pit. It did not account for the starvation that makes a man hallucinate. Although few PS were prosecuted, the shame was a prison that they built for themselves.

The Vietkong had planted a seed of self-hatred that blossomed in the safety of America. I am not a hero, the gunner thinks. I am a collaborator. This reframes every handshake, every welcome home banner. They feel like impostors. The enemy had successfully weaponized the American conscience against the American soldier. Let us zoom out to the resolution.

The years pass. 1975, 1980, 1990. The war is over. The wall is built in Washington. The names are etched in black granite. But the machine gunners are fighting a new battle. It is a battle against the ghost of the pig. Post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, was not yet a diagnosis in 1973. It was called postvietnam syndrome.

For the gunner, it manifested in specific sensory triggers. The sound of a jackhammer, the rhythmic thud, thud, thud. To a civilian, it is construction. To a former M60 gunner, it is the cyclic rate of fire. It is the sound of the ambush. There are police reports from the 1980s. A veteran in Ohio is found digging a fighting position in his front lawn at 3:00 a.m.

He is screaming for his A gunner. He is holding a rake like a machine gun. He is not crazy. He is back in the Aha Valley. The timeline has collapsed. The physical toll accelerates the aging process. The men who carried the 23-lb gun and the 60-lb ruck on a starvation diet developed early onset arthritis, degenerative disc disease, and chronic neuropathy.

Their bodies, used as mules by the US Army and then as mules by the Vietkong, simply gave out. By the time they were 50, many were in wheelchairs. The strength that made them gunners became the source of their disability. And then there is the silence. For decades, the stories of the jungle camps were not told. The narrative of the P was dominated by the pilots in the Hanoi Hilton.

Men like John McCain and Jeremiah Denton. They were officers. They were articulate. Their torture was brutal, but it was cleaner in the public imagination. The story of the grubby enlisted man in the bamboo cage covered in leech sores forced to carry rice for the enemy. That was too dark. That was too messy. So the gunners stayed silent.

They drifted into the margins. But look at the data. The suicide rates, the divorce rates. A study of Vietnam veterans suggests that those with high combat exposure, specifically heavy weapons crews, had significantly higher rates of substance abuse and suicide than support personnel. Why? Because of the responsibility, the rifleman looks out for himself.

The medic looks out for the wounded. The machine gunner looks out for everyone. When the platoon gets hit, everyone looks at the gun. Make it stop. Suppress them. When the gunner is captured, that failure to protect is total. He didn’t just get caught, he let the unit down. That guilt is a stone that no amount of therapy can fully lift.

It wasn’t until the late 1990s and 2000s with the advent of the internet and veteran forums that these stories began to surface. Men started typing their nightmares into message boards. Did anyone else have to fix guns for the VC? Did anyone else get the bamboo treatment? I thought I was the only one. The validation was the first step in healing.

They realized that the dark things were not personal failures. They were systemic torture. They were not traitors. They were victims of a calculated program to destroy their humanity. We reach the epilogue. The present day, a VFW hall in a small town in Georgia. On the wall mounted on a wooden plaque, is a deactivated M60 machine gun. The steel is cold.

The feed tray cover is welded shut. It is a museum piece. An old man stands in front of it. He is 80 years old. He leans on a cane. His hands are gnarled. He stares at the weapon. A young man, perhaps his grandson, asks, “Was it heavy, Grandpa?” The old man looks at the gun. He remembers the weight of the steel. He remembers the weight of the ammo.

He remembers the weight of the boot on his neck. He remembers the weight of the copper wire on his thumbs. He remembers the weight of the silence in the tiger cage. “Yes,” he says softly. It was heavy. He doesn’t say that he still feels it. He doesn’t say that every time he closes his eyes, he is back in the pit waiting for the grenade.

He turns away. He walks back to the bar to sit with the other old men. They don’t talk about the war. They talk about football. They talk about the weather. But when a car backfires in the parking lot, three of them flinch. They share a look, a microscopic glance that says, “I know. I was there. I heard it, too.

” The Vietkong doctrine failed in its ultimate goal. It tried to turn these men against their country and it failed. It tried to erase their identity and it failed. But it succeeded in one thing. It took a piece of them that never grew back. It took the innocence of the silence. The dark things they did to the M60 gunners were not just acts of violence.

They were acts of theft. They stole the peace of a quiet room. They stole the comfort of the dark. And that is the true legacy of the war for the men who carried the pig. The gun is gone. The jungle is gone. The enemy is gone.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.