Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944.

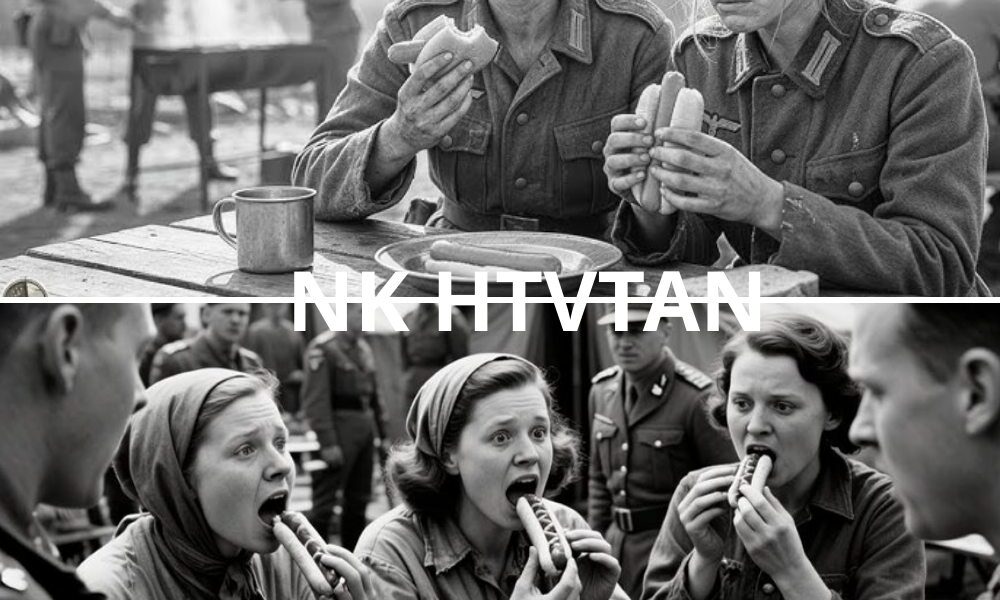

Camp Florence, Arizona. July 1944. The 4th of July celebration smelled of charcoal and frying onions. And Sergeant Maria Kaufman watched the American guards set up a strange assembly lying metal grills, split bread rolls, pink sausages that looked nothing like German worst.

Lieutenant Rachel Cohen explained through the translatter, “These are hot dogs, American tradition. one for each prisoner with all the toppings you want. Maria stared at the unfamiliar food, at the casual abundance, at guards treating enemy prisoners to holiday feast. She took a bite and tasted something beyond meat and bread.

She tasted freedom, democracy, the American casual confidence that made propaganda’s lies impossible to sustain. What happened next would change everything. Maria Kaufman was 31 years old from Stutgart had served as a communications specialist for German forces in North Africa until British troops captured her unit in Tunisia during the spring 1943 collapse.

She’d been in military service since 1941, translating intercepted radio messages. Skilled work had kept her away from front lines, but made her valuable enough that the regime had recruited women when manpower shortages became critical.

Her capture had been anticlimactic surrender negotiated by officers who’d run out of ammunition and options. Enemy soldiers who treated them firmly, but without the cruelty propaganda had promised. Helga Schneider was 28, a nurse from Hamburg who’d seen more death in most combat soldiers. She’d worked in field hospitals across North Africa, performing triage under impossible conditions, holding dying boys while artillery shells landed close enough to shower her with sand and worse.

Her medical training had been accelerated, condensed from years into months, adequate for battlefield emergency, but not proper medical education. She’d learned to amputate limbs, to prioritize who might survive over who definitely wouldn’t, to disconnect emotionally from suffering because feeling it would make the work impossible.

El Becker was 43, oldest among the prisoners at Camp Florence, a widow from Bavaria whose husband had died on the Eastern Front in Dsti, 1,941. She devolunteered for military service, partly from patriotic duty, partly from having nothing left to lose her sons or serving somewhere. In Russia, without recent word, her village had been bombed.

Her life had shrunk to waiting for news that rarely came and was never good. She’d worked in supply logistics, managing inventory for military units, keeping track of resources that grew scarcer as the war dragged on. and Germany sind industrial capacity crumbled under Allied bombing. The journey to Arizona had been long and disorienting.

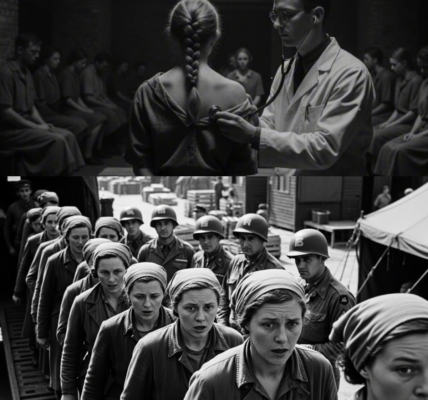

Captured in Tunisia, transferred to temporary facilities in Algeria, then shipped across the Atlantic to America, where military authorities struggled to figure out what to do with female prisoners of war. The Geneva Conventions covered combatants, but hadn’t quite anticipated women in military roles, creating bureaucratic confusion about proper housing, security protocols, and treatment standards.

The solution was segregated facilities like Camp Florence, where women prisoners were housed separately from men, guarded primarily by American female personnel, managed through regulations adapted on the fly. Camp Florence itself was new built in 1942, sprawling across Arizona desert where heat felt like physical assault and the horizon stretched forever without encountering anything humans had built before.

American military expansion brought roads and rails and structures to emptiness. The facilities were basic but adequate wooden barracks with screens against insects electricity that worked most of the time plumbing that exceeded anything. The women had experienced in North Africa mess halls that served food regularly and in quantities that challenged understanding built on years of German scarcity.

Lieutenant Rachel Cohen commanded the women’s detention section. a 32-year-old from Brooklyn whose grandparents had immigrated from Germany in the 1890s who spoke German fluently who approached her assignment with mixture of professional duty and personal complexity. Her relatives still in Germany had stopped writing in 1938 and she didn’t know if they’d survived the regime’s policies, if they’d fled, if they’d been caught in persecutions that newspapers reported, but details remained unclear. Managing German prisoners meant confronting heritage and

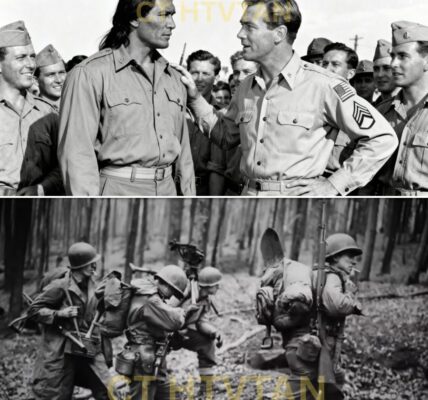

enmity simultaneously, requiring emotional discipline that wasn’t always successful. The idea came from Sergeant Williams, a guard from Texas, who de been listening to discussions about how to mark Independence Day, while managing prisoners who deing against American independence and everything it represented. “We should do a cookout,” he’d suggested to Lieutenant Cohen.

hot dogs, the whole American experience. Show them what they’ve been fighting against isn’t decadent weakness, but actual culture worth defending. Cohen had been skeptical initially feeding prisoners holiday meals seen potentially problematic might be interpreted as fraternization or excessive leniency. But the more she considered it, the more she saw strategic value, demonstrating American abundance and confidence, challenging propaganda through direct experience, treating prisoners with dignity that might influence postwar attitudes. She proposed it to the camp

commander, Colonel Thomas Henderson, who’ approved with caveat, “Keep it appropriate, maintain security, but show them American traditions. They’ve been told we’re culturally inferior, that democracy makes us weak, that our prosperity is illusion. A Fourth of July cookout, where we share our food and traditions might communicate more effectively than any propaganda we could distribute.

Just make sure the guards understand this is strategic, not social. We’re demonstrating values, not making friends. The preparations took a week. Williams requisitioned hot dogs from the camp commissary 240 of them enough for all prisoners and staff standardisssue frankfforters that tasted like childhood and summer and normaly in nation where such things remained possible despite war.

He arranged for buns, condiments, mustard and ketchup and relish that seemed excessive to people raised on German austerity. He organized grills, charcoal, cooking equipment, turning the camp’s outdoor recreation area into makeshift American celebration. The German prisoners were informed through announcements that mixed information and invitation. On July 4th, America’s Independence Day, there will be special meal featuring traditional American food.

Attendance is voluntary but encouraged. This is cultural exchange, opportunity to learn about American traditions. The prisoners received the news with suspicion and curiosity. What did American independence have to do with them? Why were capttors celebrating while captives waited for wars end? What was this food they’d never heard of? Maria disgusted with other prisoners that evening, voices low in the barracks after lights out.

It’s probably propaganda, someone suggested, making us think America is prosperous and generous when it’s all show. But Helga countered. Everything here has been show by that logic. The food, the facilities, the medical care. If it’s all propaganda, it’s remarkably consistent propaganda. Maybe we should consider that what we see is actually real.

The debate continued inconclusively, but most prisoners decided to attend curiosity outweighing suspicion. Boredom making any novelty attractive. And honestly, the promise of special food was hard to resist after years of deprivation. July 4th dawned clear and brutally hot. Arizona summer asserting itself with temperatures that would reach 105 by afternoon.

The cookout was scheduled for 1700 hours when heat would be slightly less unbearable. Sunset still hours away, evening approaching, but not yet arrived. The prisoners gathered in the recreation area where American guards had set up grills that were already smoking, charcoal glowing red, preparing for the cooking that would begin shortly.

Maria watched the setup with fascination that transcended the practical. The grills themselves were evidence of American resource deployment metal fabricated for purpose of cooking outdoors. Charcoal produced commercially and distributed for recreational use. Equipment and fuel allocated casually for holiday celebration. In Germany, metal went to military production.

Coal to industry or heating, recreational cooking was luxury from before the war. But here were Americans using resources for pleasure, for tradition, for maintaining cultural practices despite wartime priorities. The hot dogs emerged from coolers where they’d been kept cold and other casual deployment of resources, electricity powering refrigeration for food preservation, infrastructure that worked reliably enough to be taken for granted.

Sergeant Williams began grilling, the Frankfforters sizzling as they hit hot metal. Smells spreading across the area, triggering responses that were simultaneously foreign and familiar. Meat cooking was universal, but this particular preparation was distinctly American, something the German women had never encountered.

Williams worked with practice efficiency, turning hot dogs with tongs, managing the grill to ensure even cooking, clearly comfortable with process he’d performed countless times before, he explained through a translated German. These are hot dogs, Frankfarters, technically, though they’re American version rather than German original.

We grill them, put them in buns, add whatever toppings you like. Traditional Fourth of July food, simple but good, part of American culture since the 1800s. The serving line formed with prisoners uncertain but curious. The process was straightforward. Receive a hot dog in a bun, move down the line, adding desired toppings.

mustard, ketchup, relish, chopped onions, sauerkraut for those wanting something closer to German familiarity. The choices were individual, personal, nobody dictating what combinations were acceptable, small freedom. It felt symbolically significant to women whose lives had been regulated by military and then captivity for years.

Maria chose mustard and onions, avoiding ketchup that looked too sweet. Taking sauerkraut that provided familiar taste, even if the overall construction was alien, she found a seat at one of the picnic tables that had been set up, wooden structures painted white, distinctly American in their casual functionality. She held the hot dog uncertainly, examining it the pink sausage, the soft white bun, the yellow mustard, and translucent onions.

It looked almost comical, not quite serious as food, too casual for proper meal, but the smell was undeniably appealing, savory, and rich, triggering hunger that went beyond mere nutrition. She bit into the hot dog and experienced cascade of sensations that were simultaneously strange and delightful. The sausage had snapped to it, casing giving way to softer interior, texture different from German worst, but not unpleasantly so.

The bun was sweet, softer than bread, she remembered, compressing under her teeth. The mustard was sharp, cutting through the meat’s richness. The onions added crunch and slight bitterness. Together, the components created flavor profile that was unsophisticated but effective comfort food that didn’t pretend to be oat cuisine but succeeded completely at being satisfying.

She chewed slowly, swallowed, and felt something unexpected. Joy. Not happiness exactly. Her circumstances were still captivity. Still uncertainty about family back home. still grief for everything lost. But this simple food, this casual American tradition, this moment of eating something purely for pleasure rather than necessity, it triggered emotions she’d forgotten was possible. Food could be fun.

Eating could be enjoyable rather than just sustaining. That recognition felt revolutionary after years when every meal was calculated for survival value. around her. Other prisoners were having similar reactions. Helga Schneider ate her hot dog with the methodical attention of someone analyzing medical procedure, assessing each component, determining overall effectiveness.

She’d chosen ketchup and relish combination that created sweet tangy flavor she’d never encountered. “It’s good,” she said to Maria with surprise audible in her voice. Not complex, not sophisticated, but genuinely enjoyable. I haven’t eaten something just for pleasure in years. Even before capture, military food was fuel, not celebration.

This feels almost decadent. Else Becker had loaded her hot dog with sauerkraut, seeking familiar flavor in unfamiliar context. She ate it slowly, thoughtfully, her expression cycling through skepticism, “Surprise, acceptance.” When she finished, she looked at the empty paper plate and said quietly, “This is what prosperity creates space for simple pleasures.

Resources deployed for enjoyment rather than just necessity.” Germany hasn’t had this since before the war, maybe longer. We called Americans weak for caring about comfort and pleasure. But maybe caring about those things is what strong societies do when they resecure enough to afford it.

The observation was philosophical, almost melancholy, but it captured something fundamental that was shifting in the prisoner’s understanding. American abundance wasn’t weakness or illusion. It was what systems produced when they functioned properly. when economies generated surplus rather than extracted every resource for military purposes. When societies valued civilian happiness alongside military effectiveness.

After the initial serving, Sergeant Williams and other American guards circulated among the prisoners, answering questions about hot dogs and Fourth of July traditions. The conversations were carefully supervised. Lieutenant Cohen had instructed guards to maintain appropriate professional distance while still engaging in cultural exchange.

The line between fraternization and education was thin, but Cohen believed navigating it was worth the risk. Maria found herself talking with Williams through the translator, asking about hot dog origins and American food culture. Williams explained with enthusiasm that suggested he de been waiting for someone to ask.

Hot dogs came from German immigrants actually frankfurters from Frankfurt but Americans adapted them made them ours. We simplified the recipe standardized production created whole culture around them. Their baseball game food, picnic food, summer cookout staples. Not fancy, not trying to be, just good, reliable satisfaction that everyone can afford and enjoy. The democratization of food struck Maria as significant.

In Germany, quality meat was luxury, accessible primarily to wealthy or connected. But Williams was describing food culture where basic satisfaction was universal, where everyone could access the same simple pleasures regardless of class or status. that seemed fundamentally different from German social structures, from hierarchy that permeated everything, including dining.

Helga asked about American medical care, curious whether the abundance she’d seen in Camp Infirmary extended to civilian life. Cohen answered this question personally, describing her experience growing up in Brooklyn, the local doctor who treated everyone regardless of ability to pay.

the hospitals that were well equipped, if not perfect, the general sense that healthc care was right rather than privilege. She acknowledged problems, poverty, discrimination, inequality, but emphasized that the overall trajectory was toward expanding access rather than restricting it to elites. The conversation was carefully balanced between honesty and strategic messaging. Cohen wanted to present America accurately while also highlighting values that contrasted with German regime’s approach.

She wasn’t lying, but she was curating, emphasizing aspects of American society that demonstrated principles that prisoners might carry home when eventually repatriated. El found herself discussing agriculture with a guard from Iowa, comparing German and American farming. The guard described family farm that sprawled across acreage that would have sustained entire Bavarian village.

Mechanization that allowed few people to produce enormous quantities, economic systems that rewarded efficiency and generated surplus. Else listened with the attention of someone whose entire worldview was being challenged, whose assumptions about German agricultural superiority were dissolving under evidence of American capacity.

As evening approached and temperature dropped from unbearable to merely oppressive, the camp prepared for fireworks display. This raised security concerns, explosives near prisoners, potential for panic or manipulation. But Colonel Henderson had decided the risk was manageable and the symbolic value worth it. The prisoners would see American celebration, American confidence, American willingness to make noise and light and spectacle even in wartime. Even with enemies present, the fireworks began at 2030 hours.

Full darkness, desert sky, providing perfect backdrop. The first explosion made Maria flinch combat reflex, expecting incoming rather than celebration. But subsequent bursts came in rhythm and color that was clearly intentional, artistic rather than destructive. Explosions that created beauty instead of death.

Red and white and blue patterns filled the sky, accompanied by American patriotic music from speakers that had been set up, combining visual and auditory display into total sensory experience. Maria watched the fireworks and felt tears on her face without quite understanding why. Partly it was beauty. She’d forgotten that humans created spectacular things for no reason beyond joy and tradition.

Partly it was the contrast in Germany. Explosives meant death and destruction. Here they meant celebration. Partly it was recognition of what American confidence looked like. Deploying resources for pleasure. Making noise and light without fear of enemy retaliation. Maintaining cultural traditions despite war that should have eliminated anything non-essential.

Helga watched with medical detachment that couldn’t quite hide emotional response. She’d treated burns from explosions, amputations from shrapnel, trauma from sustained bombardment. Seeing explosives used for beauty rather than harm felt almost offensive initially, then gradually transformative.

What kind of society, she wondered, had such security that they turned weapons into art? What did that say about their military strength, their economic capacity, their fundamental confidence in victory? else watched the fireworks and thought about her sons in Russia, about her dead husband, about the village in Bavaria that had been bombed and might be bombed again.

She wondered if they were watching anything beautiful, if they had moments when horror paused and beauty could exist, if there was anything in their experience comparable to this American certainty that pleasure was permissible even in wartime. She doubted it. Germany was survival mode. every resource devoted to military necessity. No space for beauty or joy or traditions that didn’t serve propaganda purposes.

The fireworks lasted 20 minutes, finale building to crescendo of color and sound that felt excessive and wonderful simultaneously. When it ended, the prisoners sat in darkness that felt profound after the display, silence that seemed weighted with meaning. Lieutenant Cohen had the translatter announce.

This is what Americans fight for, the right to celebrate, to maintain traditions, to create beauty even in difficult times. This is what democracy protects. Not just survival, but space for joy, for culture, for the things that make life worth living beyond mere existence. The message was clear propaganda, but it was propaganda supported by evidence the prisoners couldn’t deny.

They’d eaten American food, watched American celebration, experienced American abundance firsthand. Arguing that it was all illusion required rejecting their own direct experience, choosing ideology over reality, maintaining beliefs that contradicted everything they’d observed. That night, in the barracks after prisoners returned from the cookout, the discussions were intense and conflicted.

Some women remained suspicious, arguing that generous treatment was manipulation designed to break the resistance, that accepting American hospitality meant betraying German loyalty. But most found themselves unable to maintain that position convincingly, unable to reconcile suspicion with evidence of consistent, decent treatment.

Maria wrote in her diary, a practice she’d maintained throughout captivity, documenting experiences in German script she hoped might someday help her remember or understand. Today we celebrated American Independence Day. They served us hot dogs, which are simple sausages and bread, but somehow capture something essentially American, unpretentious, accessible, satisfying without being fancy.

Then fireworks, explosions turned into art, resources deployed for beauty and tradition despite wartime pressures. I keep thinking about what this says regarding everything we were told. Propaganda insisted Americans were weak, their culture shallow, their prosperity elucory, their democracy chaotic. But I’ve eaten their food, lived in their facilities, experienced their systems, and none of propaganda’s claims match observed reality. They’re not weak.

They’re so strong they can afford generosity to enemies. Their culture isn’t shallow. It just values different things than German culture emphasized. Values access and democracy over hierarchy and tradition. Their prosperity isn’t illusion. It’s visible in every meal, every facility, every casual deployment of resources for purposes beyond bare survival.

I don’t know what happens when we’re eventually repatriated. I don’t know what Germany will be after defeat that now seems inevitable, but I know I’ll carry these observations home. will remember that enemies showed mercy, that propaganda was comprehensively false, that societies can be evaluated by how they treat those with least power, including prisoners, who theoretically deserve nothing but are given dignity anyway.

Helga’s reflections were more clinical, analyzing the experience through medical lens. The hot dog itself is interesting from nutrition perspective. Protein, carbohydrates, fats in ratios that provide energy and satisfaction. But more interesting is what it represents. Democratization of food quality. Idea that everyone deserves access to satisfying meals regardless of status.

In Germany, medical care and food quality tracked with social hierarchy. Here prisoners literally the lowest status individuals receive nutrition that would be envied by German civilians. That tells you something fundamental about resource distribution and values.

The fireworks were pure symbolism converting military technology into civilian celebration, demonstrating confidence and security through wasteful beauty. No nation creates fireworks unless they have explosives to spare. Resources beyond military necessity, confidence that enemies can’t exploit the vulnerability of celebration. Germany stopped all non-essential activities years ago.

America hosts cookouts with prisoners and shoots fireworks into the sky. That asymmetry explains the war’s outcome more clearly than any military analysis. else wrote letters to her sons that might never reach them might be read by sensors who dean analyze them for intelligence value. Today I ate an American hot dog and watched fireworks celebrating their independence from monarchy and hierarchy.

I thought of you both constantly wondered if you’re eating adequately, if you’re safe, if you’ll survive to see whatever Germany becomes after this war ends. The Americans have been kind to us in ways I didn’t expect and maybe don’t deserve. They feed us well, treat us with basic dignity, maintain systems that work reliably. I don’t think this is deception.

I think it’s just how their society functions when properly resourced. They have so much capacity that they can afford mercy, can treat enemies with decency because the cost is minimal relative to their total resources. I hope you survive this war. I hope Germany survives in some form worth living in.

And I hope that what I’m learning here about how to treat people, about what prosperity enables, about values that transcend nationalism, I hope I can share those lessons with you someday when we are reunited. Until then, know that your mother is safe, is fed, is learning difficult truths about everything we believed. The Fourth of July cookout became template for other American cultural education.

Lieutenant Cohen organized regular events where prisoners could experience different aspects of American food culture. Pancakes for breakfast on weekends, hamburgers for summer barbecues, apple pie that prisoners learned to make with American cooks teaching techniques. Each food item became lesson in American abundance and values in what societies produced when systems function properly.

Maria found herself particularly drawn to baking lessons working with American cooks to learn about American desserts apple pie with its flaky crust and cinnamon spiced filling chocolate cake that was richer than anything she’d dee in Germany cookies that combined sweetness with textures she dee never encountered.

The baking was educational, but also therapeutic, giving her skills and knowledge she could carry forward, ways to create pleasure for others that transcended nationality or wartime allegiance. The American cooks who taught her were generous with knowledge, sharing recipes and techniques without proprietary concerns.

This struck Maria as distinctly American, a willingness to share information freely, to help even enemies learn, to treat knowledge as abundant resource rather than scarce commodity requiring hoarding. In Germany, professional knowledge was guarded. Competition emphasized success zero sum.

But these American cooks acted as if Maria’s success increased rather than decreased their own value. Helga integrated into the medical program more thoroughly, working alongside American doctors and nurses, learning their techniques and systems. She was struck by their emphasis on standardization protocols that everyone followed, quality control that ensured consistent care, systems thinking that prioritized population health over individual practitioner autonomy.

German medicine had been craftoriented, hierarchical with senior physicians maintaining practices based on personal judgment. American medicine was becoming more systematic, collaborative, focused on replicable best practices. The Americans were willing to teach her everything, to share medical knowledge with someone who’d recently been enemy combatant. This generosity with professional expertise suggested confidence they were ant worried about.

Germans learning American methods because they believed their systems were good enough, innovative enough, adaptable enough to maintain advantages. That confidence was itself educational, demonstrating what security looked like when it came from genuine strength rather than proclaimed superiority. By October 1944, Maria had become something like assistant cook, helping prepare meals for her fellow prisoners, applying techniques learned from Americans while adapting them to German pallets.

She made apple pie with more cinnamon and less sugar, hamburgers seasoned with carowway seeds, hot dogs served with proper German mustard when available. Diffusion cuisine pleased both prisoners and American staff, demonstrating that cultures could combine rather than requiring one to dominate.

Her work in the kitchen gave her purpose beyond mere survival, skills that would be valuable in whatever came after the war. She began imagining opening a restaurant in Stoutgart if Stogart still stood. If Germany survived defeat, if civilian life became possible again, she’d serve American German fusion food, introduce Germans to hot dogs and hamburgers while maintaining traditional dishes, create space where both cultures could coexist and learn from each other.

The dream felt improbable but sustaining, giving her reason to think about futures rather than just surviving present. Helga had similar professional transformation. her medical skills improving through American training, her understanding of public health systems, expanding through observations of how the camp clinic functioned. She began planning to return to medical education after the war.

If Germany had functioning universities, if medical training was possible, if reconstruction created opportunities rather than just struggle, she’d teach American methods, advocate for systematic approaches, push Germany toward medicine that emphasized access and quality over hierarchy and tradition. Elsa’s transformation was more philosophical than professional.

She’d worked in logistics for years, understood resource management, but American abundance challenged her basic assumptions about scarcity and distribution. She began writing detailed notes about American system, how supplies were ordered, how quality was maintained, how distribution worked to ensure consistent availability.

She planned to apply this knowledge to German reconstruction to help build systems that generated surplus rather than merely managing scarcity. The three women different ages, different backgrounds, different roles were all undergoing similar fundamental shift from believing propaganda to trusting evidence from assuming American weakness to recognizing American strength from viewing enemies as inferior to understanding them as different. from thinking conflict was inevitable to imagining cooperation might be possible.

December brought the prisoners first American Christmas and Lieutenant Cohen organized celebration that integrated German and American traditions. The menu planning became collaborative project German prisoners working with American cooks to create meals that honored both cultures.

The result was feast that would have been impossible in Germany. Roast turkey prepared American style served alongside German red cabbage and potato dumplings. American rolls and German stolen pumpkin pie and leken cookies. But the centerpiece almost as joke that became genuine tradition was hot dogs. Sergeant Williams prepared them as he had for 4th of July. But this time prisoners requested them specifically.

wanted them included in Christmas meal because they’d become symbol of American generosity, of cultural exchange, of transformation from enemy to something more complicated. The hot dogs at Christmas dinner represented acceptance of American culture, of changed circumstances, of the reality that propaganda had been comprehensively wrong. Maria helped prepare the meal, working in the kitchen alongside American cooks and German prisoners.

The collaboration seamless by now. She’d learned American techniques, taught German methods, created hybrid approaches that combined best of both traditions. The Christmas dinner was culmination of 6 months education. Demonstration that cultures could coexist rather than requiring one to eliminate the other.

The meal was served at 1700 hours. Prisoners and guards eating at decorated tables. Christmas carols playing from speaker German and American songs alternating. Silent night sung in both languages. Music bridging what politics had divided. Maria sat with Helga and else, the three women who’d arrived suspicious and frightened, now eating Christmas dinner that exceeded anything they’d experienced in Germany even before the war.

Else looked at her plate turkey and hot dog side by side, American and German foods combined, and said, “This is what peace might look like. Not one culture defeating another, but both learning to coexist, to appreciate what each offers, to build something richer than either achieved alone.

I don’t know if that’s possible at national level, but at this table right now, it’s real. That gives me hope. The war in Europe ended May 8th, 1945, and repatriation planning began, though execution would take months. Maria received notification in August that she’d be sailing in October, returning to Bremen, and then making her way to wherever Stoutgart had become.

She spent her final weeks at Camp Florence, documenting everything she’d learned, recipes, techniques, systems, observations about American culture and values. She filled notebook with information she could carry home. Knowledge that might help rebuild Germany from defeat’s ashes.

Her last week, Sergeant Williams organized a final cookout. One more round of hot dogs is farewell to prisoners who’d become something between charges and friends. He grilled with the same casual competence he’d shown that first Fourth of July, but the emotional weight was different now, not demonstrating American culture to suspicious enemies, but sharing tradition with people who’d come to appreciate it.

Maria ate her final American hot dogs slowly, savoring flavors that had become familiar, thinking about the journey from suspicion to acceptance, from propaganda certainties to evidence-based understanding. This simple food frankfer in bun, mustard, and onions had been gateway to larger education about prosperity and generosity about what strong societies looked like when they could afford mercy about enemies who proven more decent than propaganda had prepared her to expect. She kept the paper plate from that final meal. Writing on it in English she’d learned

during captivity. My last American hot dog, October 12th, 1945. Thank you for showing me that enemies can be kind, that propaganda lies, that food can be bridged between cultures. I’ll l carry these lessons home and tried to build Germany worthy of the mercy you showed us.

She packed the plate with her notebooks, fragile artifacts that would survive journey home and remain treasured possessions for decades. Helga sailed in November, returning to Hamburg that no longer existed as she’d known it. City reduced to rubble, infrastructure destroyed, population starving and traumatized.

She brought medical knowledge learned from Americans, systems thinking that would help rebuild German healthcare, conviction that enemies could teach valuable lessons if pride didn’t prevent learning. She wrote to Lieutenant Cohen in 1946 thanking her for treatment that exceeded Geneva Convention requirements, for education that prepared her for reconstruction work, for demonstrating that victory didn’t require brutality.

El returned in December to find her sons had both survived, barely wounded and psychologically damaged, but alive. She used logistics knowledge learned from observing American systems to help organize food distribution in Bavaria, applying efficiency methods that made scarce resources stretch further.

She never forgot the lesson of hot dogs and fireworks, that prosperity created space for pleasure, that strong societies valued civilian happiness, that German militarism had sacrificed joy for power and achieved neither. Maria Kaufman lived until 1997, dying at age 84, having opened the Stoutgart restaurant she dreamed about in captivity.

It served American German fusion food, introduced Germans to hot dogs and hamburgers properly prepared, maintained traditional dishes while incorporating new techniques. The restaurant became gathering place where Maria told stories about American captivity, about enemies who’d shown mercy, about propaganda demolished by hot dogs and fireworks. She kept the paper plate in a frame on the restaurant wall artifact from October 1945.

Her last American meal before repatriation, physical evidence of transformation from enemy to student to someone who’d learned that cultures could coexist. Customers asked about it occasionally, and Maria would explain, “That plate represents the moment when I learned enemies could teach valuable lessons.

When propaganda mech reality and couldn’t survive the collision. When simple food became education about what strong societies look like when they can afford generosity.” Her grandchildren found her notebooks after her death pages documenting American recipes and techniques, observations about culture and values, reflections on what she’d learned during captivity.

They donated them to museum documenting German P experiences, where they sit alongside thousands of similar testimonies about propaganda dissolving under evidence, about enemies showing unexpected mercy, about food becoming bridged between cultures that war had divided. The hot dog itself, that simple American staple, had been more than meal.

It had been demonstration of abundance, proof that propaganda lied, evidence that American culture wasn’t shallow, but valued accessibility and pleasure, symbol of generosity that enemies had shown when cruelty would have been justified. That 18-month education through meals and traditions and consistent decent treatment had transformed 37, germing women from suspicious enemies into people who understood that the other side was human, too.

that their culture had value worth respecting, that peace required finding common ground rather than requiring one side to dominate completely. Sergeant Williams kept photograph from that first Fourth of July cookout German prisoners eating hot dogs, expressions mixing suspicion and surprise and gradual acceptance.

He displayed it in his Texas home, and when grandchildren asked about it, he Dex explained, “Those were enemy prisoners.” I fed American hot dogs to show them our culture wasn’t weak or shallow like they dee been told. Food became our weapon, not to hurt them, but to challenge their certainties, to demonstrate that prosperity and mercy could coexist, that winning war was different from winning peace, and that sometimes the best way to defeat an ideology was to prove it wrong through kindness rather than just violence. The hot dog invented by German

immigrants, adapted by Americans, served to German prisoners in Arizona desert had come full circle. Symbol of cultural exchange and transformation that war had tried to prevent but ultimately enabled not through combat or conquest but through simple act of sharing food and tradition with people who de taught to expect cruelty and instead received mercy that changed everything.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.