German Mother Begged American Soldier for Food, What He Did Next Shocked Her

March 1946, in the American zone of Berlin, snow was falling in thick, muffled flakes, softening the edges of a city that had been smashed to pieces.

Anna Schäfer, twenty-eight, walked down a ruined street with a four-year-old boy on her hip and her six-year-old daughter clinging to her coat. All three wore whatever coats they’d managed to find. Their faces were thin, cheekbones too sharp, eyes too big in hollow sockets. The children hadn’t eaten properly in weeks. Anna herself hadn’t eaten in three days so the little ones could share half a boiled potato each.

Ahead of her, a lone American soldier walked his patrol. Tall, clean uniform, helmet pushed back, rifle slung easy across his chest. Private First Class James O’Connor, twenty-two, from Brooklyn, was chewing gum and looked almost bored, until he saw the woman and the two small shadows beside her.

Anna scraped together what courage she had left. She stepped into his path and spoke in halting, cracked German, her voice raw from cold and shame.

“Bitte… my children are starving. Do you have anything? Anything at all?”

She braced for a shove, a shout, a raised rifle. That was what the radio had warned of. That was what neighbors whispered Americans did.

Instead, the soldier stopped chewing. His gaze went from the little boy’s blue lips to the girl’s twiglike fingers gripping her mother’s coat. James reached into his field jacket and pulled out a Hershey bar. Then another. Then a small tin of Spam. Then a pack of Wrigley’s gum.

He knelt down so he was eye-level with the children and held the chocolate out. The girl stared at it like it was made of gold. She didn’t move. She’d been taught never to take anything from the enemy. Anna began to cry silently. Tears froze on her cheeks.

“It’s all right, Liebling,” she whispered. “Take it.”

Still the girl hesitated. James unwrapped one bar, snapped off a square, popped it into his own mouth, and chewed, smiling.

“See? Good,” he said.

Only then did the girl reach out with trembling fingers.

James wasn’t finished. He stood, glanced up and down the empty street, then beckoned to Anna to follow. She hesitated, fear knotting her stomach. It could be a trick. He waited. Finally, she walked after him.

Ten minutes later they reached an American mess tent on the edge of the district. Inside, it smelled of coffee and real bread. GIs looked up, curious. James spoke quickly in English to the cook sergeant. The sergeant nodded, disappeared, and came back carrying a metal tray loaded for three: thick slices of warm rye bread with butter, two fried eggs each, powdered milk already mixed, and a bowl of canned peaches in heavy syrup.

Anna stopped dead in the doorway. She hadn’t seen that much food in one place since 1941.

James pulled out chairs for the children and then for her. The boy clambered up and immediately began eating with his hands. The girl tried to be polite, but hunger won and she ate the same way. Anna tried to say thank you in broken English. No one understood the words, but everyone understood the tears.

When the plates were empty, the cook refilled them without being asked. James found a paper bag and filled it with more bread, two cans of beans, a jar of peanut butter, another chocolate bar. He pressed it into Anna’s hands.

She looked from the bag to his face. “You are feeding the children of your enemy,” she said in German.

James shrugged, embarrassed. “Kids didn’t start the war, ma’am.”

That night, back in the freezing basement room they called home, Anna lit their single candle. The children fell asleep with chocolate still smudged on their lips. She sat at the edge of their mattress and opened the paper bag again just to be sure it was still real.

The next morning, she went back to the same street corner. James was there. This time she carried something wrapped in newspaper: a small porcelain angel, the only unbroken thing she still owned from before the bombs. She pressed it into his hand. When he tried to give it back, she closed his fingers over it and used the phrase she had practiced all night.

“Thank you for my children.”

For the next three weeks, James brought extra rations whenever he could. Some days it was a can of peaches, some days powdered eggs, some days a blanket “borrowed” from the supply tent. The children began to laugh again. Color crept back into their cheeks. Anna’s strength returned. Her milk came in for the baby she was expecting in two months.

Then James rotated home. One day he was simply gone. Anna went to that corner for weeks hoping to see him, to say goodbye properly. He never came. She kept the porcelain angel on their table instead, a silent stand-in for the American who had changed everything.

Years passed. With the help of care packages and Marshall Plan aid, Anna trained as a nurse. Klaus, the little boy whose lips had once been blue in that Berlin winter, grew up to be an engineer who helped rebuild the autobahn. Liesel studied languages and became an English teacher. Baby Peter, the child still in her belly when James handed over canned peaches and bread, went to medical school.

In December 1962, in Brooklyn, James O’Connor—now forty, married, with three kids of his own and working as a fireman—came home from a shift to find a thin airmail envelope on the kitchen table. West German stamps ran across the corner.

His wife said, “It’s in English, but the writing’s careful—like someone practiced every letter.”

He opened it. A photograph slipped out first: three tall teenagers, two boys and a girl, standing in front of a rebuilt apartment block. On the back, in neat English:

To Private James O’Connor.

You once told my mother children didn’t start the war. Because of you, we got to grow up.

Your German family,

Anna, Klaus, Liesel, and little Peter.

He read it twice, then sat down hard. His wife asked what was wrong. He handed her the photograph.

“These are my German kids,” he said simply.

He had never told anyone the full story. Only that he’d tried to help one family in Berlin. Now that family had found him through the Red Cross tracing service.

Anna’s letter—four pages—told the rest. After he left, she’d gone to that corner every day but never saw him again. She’d kept the porcelain angel on the table and each year on their birthdays the children kissed it and said, “Danke, American Daddy,” before eating cake.

She wrote about her training as a nurse, about Klaus’s work as an engineer, about Liesel’s classroom, about Peter in medical school. At the bottom, one more line:

If you ever want to visit, our door is open. You will never pay for a meal in our house. Never.

James showed the letter to the guys at the firehouse. They took up a collection. Six months later, in the summer of 1963, James, his wife, and their three children flew to Frankfurt.

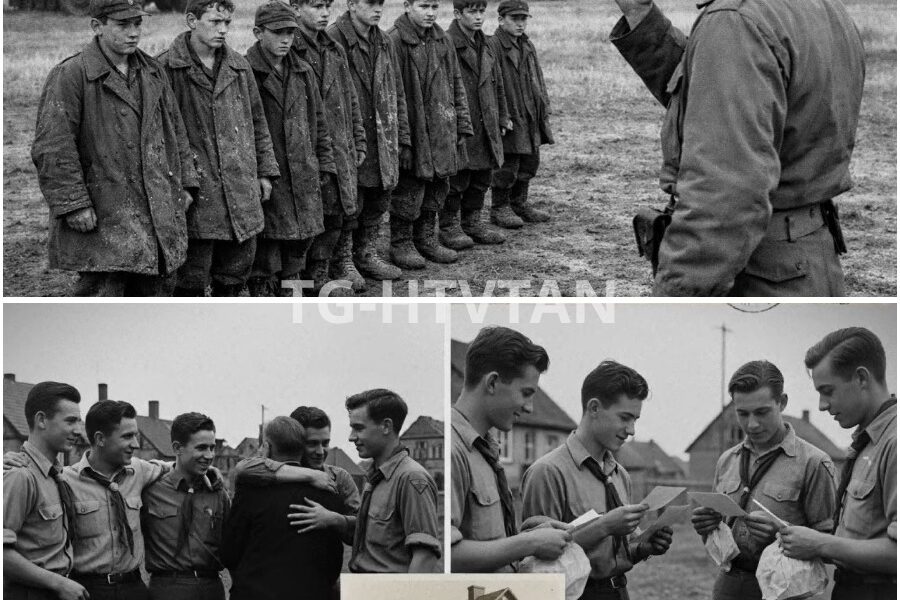

Anna and her children met them at the airport. The reunion photograph made the local paper: an American fireman hugging three Germans who now towered over him, everyone crying under the arrival hall lights.

For two weeks, James was treated like royalty. Anna insisted he take the best bed, the biggest steaks, the last piece of bread. He wasn’t allowed to lift a finger. At night, the teenagers begged for stories about Brooklyn. In the backyard, James taught them how to throw and catch a baseball.

On the final evening, Anna took him to the shelf where the porcelain angel still stood. Its glaze was a little crazed with age, but it was intact.

“We survived because of you,” she said quietly. “Germany survived because of men like you.”

James tried to deflect it. “I just gave away some extra K rations,” he joked, voice breaking.

Anna shook her head. “No. You gave us tomorrow.”

Forty years later, in 2003, another letter arrived addressed to the same Brooklyn firehouse. This time it was from Peter, now a successful heart surgeon in Munich. Inside was an invitation to his wedding—and a plane ticket, already paid for.

James, now eighty, gray-haired and retired, boarded the flight with his grandchildren. At the reception, the bride and groom introduced him not as a guest, but as “our American grandfather.” When the band played the first dance, Peter’s new wife led James onto the dance floor before anyone else. The whole room rose to its feet and applauded.

In 2011, at eighty-eight, James died peacefully in his sleep. At his funeral in Brooklyn, among the firemen in dress uniforms and the bagpipes skirling, four tall Germans stood near the front: Klaus, Liesel, Peter, and their mother Anna, now in her nineties, who had flown over one last time.

When the service ended, Anna stepped forward. In her hands she held the little porcelain angel. She placed it gently on his casket.

The priest read the line she had asked him to include:

“He shared his bread with my children when the world had no bread left. Because of him, three generations carry kindness in their hearts.”

Sometimes one chocolate bar on a bombed-out street, one hot meal in a cold city, becomes a bridge that lasts a lifetime and beyond.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.