This Is the Best Food I’ve Ever Had” — German Women POWs Tried American Food for The First Time. US.

This Is the Best Food I’ve Ever Had” — German Women POWs Tried American Food for The First Time

On May 8th, 1945, the war in Europe was over.

In a dusty field outside the ruined city of Darmstadt, Germany, thirty-eight women still wore the gray uniforms of the Wehrmacht. They were the last female auxiliaries of the Luftnachrichten—Helferinnen from the signal corps who had operated radios, telephones, and radar stations until the final hour. They were between eighteen and twenty-nine years old. Some had volunteered. Some had been conscripted. All of them were now prisoners.

They sat in rows on the ground, knees drawn up, surrounded by American GIs with rifles. Their faces were thin, cheekbones sharp, eyes too large in their pale faces. Their hair was cropped short under caps that no longer carried insignia. They had not eaten properly since February. The last official ration—three days earlier—had been a cup of watery soup and a slice of sawdust bread.

They knew what might happen next. They had heard stories. They had been told the Americans would take revenge. They waited for shouting, for blows, for the worst things they could imagine, and they waited quietly, because that was what German women had been taught to do when the world ended.

But the Americans were not shouting.

A young lieutenant from Texas named Daniel O’Connell walked forward. He was twenty-four, with a baby face and a drawl as thick as molasses. In the past month he had seen too many concentration camps. He had also seen his own men hand chocolate to starving French children. He looked at the women, some barely older than his little sister back home, and made a decision.

He turned to his sergeant. “Bring the kitchen truck up.”

Ten minutes later, two field kitchens rolled forward. The smell drifted across the field—real coffee, frying Spam, powdered eggs, biscuits baking in portable ovens. The women smelled it and didn’t believe it. Some began to cry without sound.

Lieutenant O’Connell walked along the rows with a clipboard. Through an interpreter, he asked if any were wounded or sick. A few raised their hands. He marked their names. Then he did something none of them expected.

He took a mess tin and piled it high with scrambled eggs, two biscuits dripping with butter, a thick slice of Spam, and a spoonful of peach jam from a 10-in-1 ration. He walked to the first woman in the front row, nineteen-year-old Erika Müller from Hamburg, and held it out.

Erika stared at the food as if it were a trick. She had never seen so much in one place. The lieutenant smiled—a small, ordinary smile, but one with no anger in it. In careful German he had learned from prisoners, he said, “Essen, bitte. Eat, please.”

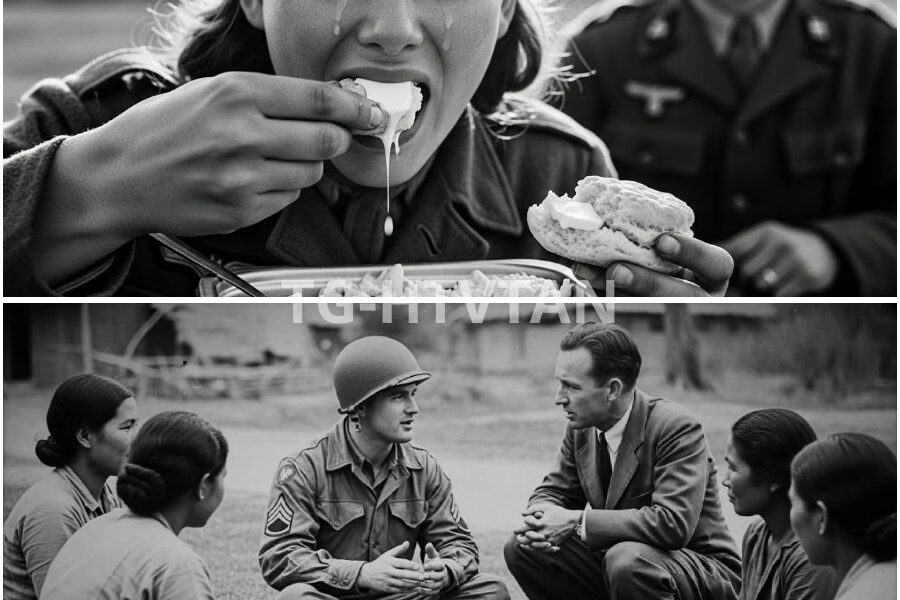

Her hands shook so badly the tin rattled. She took one bite of the eggs. Her eyes closed. Tears rolled down cheeks still dusted with airfield soot.

“This is the best food I’ve ever had,” she whispered.

O’Connell didn’t understand the words, but he understood the look. He moved to the next woman, and the next. Within minutes, every woman held a full mess tin. Some ate slowly, terrified it would be taken away. Some ate so fast they choked and cried at the same time. Some simply held the warm tin against their chests and rocked.

Private Ruth Becker, twenty-one, from Munich, had not tasted butter since 1942. She spread it thick on the biscuit, licked the knife clean, and then started crying so hard she couldn’t swallow. Corporal Elsa Klöne, twenty-seven, the eldest, a mother of two boys she had not seen in two years, took a sip of real coffee with canned milk and sugar. She closed her eyes and mouthed “Danke” over and over.

The American soldiers watched in silence. Many had sisters, wives, sweethearts. Some had daughters. One GI pulled a Hershey bar from his pocket and handed it to the girl beside him without a word. Another lit a Lucky Strike and passed the pack down the row. Soon the air was full of cigarette smoke and the sound of women trying not to sob while chewing.

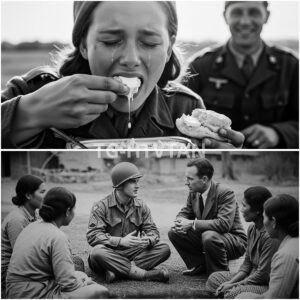

Lieutenant O’Connell sat on the ground with them. Through the interpreter, he asked where they were from, what they had done in the war, whether they had families. The answers came slowly at first, then in a rush. They were terrified of being judged, of being condemned for uniforms they no longer believed in. O’Connell only nodded. He told them about his little sister in San Antonio who was learning to drive the tractor.

The women laughed. Small, broken laughs, but real.

Night fell.

Instead of being loaded onto trucks and dragged off to unknown camps, they were given blankets. Real wool blankets, smelling of mothballs and America. They were told they would sleep in a barn that night under guard, but with a roof over their heads and straw for bedding. Before they left the field, each woman received a small paper bag.

Inside were two Hershey bars, a pack of Lucky Strikes, a tin of Spam, and a handwritten note in German:

“You were doing your duty. We were doing ours.

The war is over. Welcome to the human race again.

87th Infantry Division, U.S.A.”

Years later, many of those women would keep that note in a drawer or a Bible for the rest of their lives. Erika framed hers. She would marry an American soldier in 1949 and move to Wisconsin. Every Christmas, she baked biscuits with too much butter and told her grandchildren about the day the “enemy” fed her like a daughter.

Ruth Becker opened a small bakery in Bremen. The first thing she learned to bake perfectly was American biscuits. She named the shop “Danke 1945.”

Elsa found her two sons alive in a displaced persons camp. The first real meal she cooked for them when they were reunited was scrambled eggs with Spam. They each ate three helpings and asked why “Mutti” was crying into the frying pan.

In 1978, thirty-three years after that dusty field outside Darmstadt, twenty-one of the original thirty-eight women met there again. They brought their children, their grandchildren, and their American husbands. They laid a wreath on the spot where the kitchen trucks had once stood and read aloud, one by one, the note they still carried.

Because some moments are bigger than victory or defeat. Some moments are simply the first time someone looks at you and sees a human being instead of an enemy.

On that day in May 1945, thirty-eight German women discovered that peace does not always begin with treaties. Sometimes it begins with a plate of scrambled eggs, a biscuit dripping with butter, and a young lieutenant from Texas who decided that hunger has no uniform.

And for the rest of their lives, whenever they tasted real butter or smelled coffee brewing, they heard that soft voice again across the years:

“Essen, bitte. Eat, please. You are home now.”

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.