Testimonies Documents And Whispers At The End Of World War Two That Still Demand Answers Today From Those Who Were Once Prisoners. NU.

Testimonies Documents And Whispers At The End Of World War Two That Still Demand Answers Today From Those Who Were Once Prisoners

“It hurt when I sat down.”

The sentence was short, almost casual, and spoken decades after the war had ended. It was not shouted in a courtroom or written in a headline at the time. It appeared in a quiet interview, recorded long after uniforms were folded away and medals had lost their shine. For years, it meant little to anyone who heard it. Then, slowly, it began to matter.

That simple phrase became a key. Not a full confession, not an accusation written in legal ink, but a human signal pointing toward something buried under layers of victory narratives and official silence. It suggested that the end of war did not end suffering for everyone, and that some wounds were carried not on the chest but deep within daily life, remembered each time a chair scraped the floor.

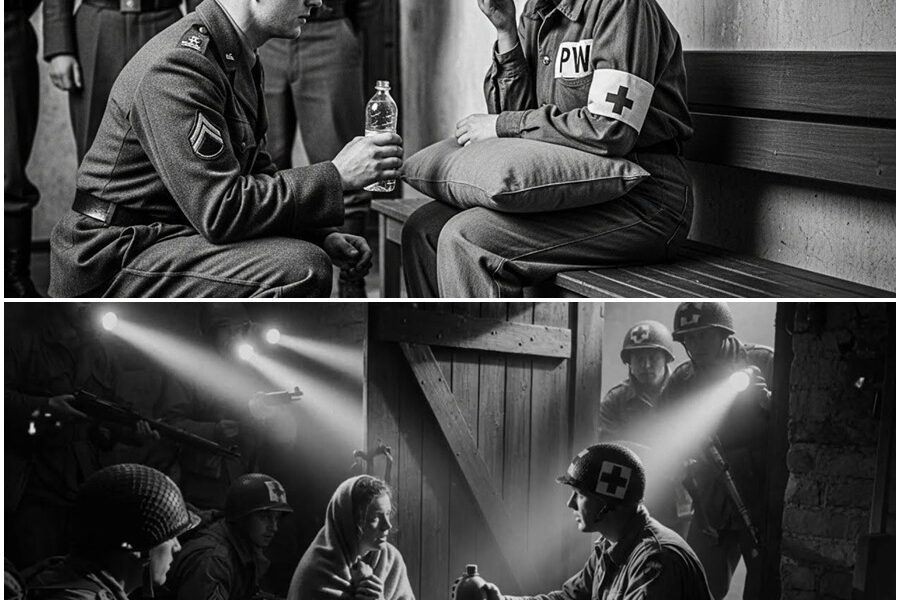

This article explores what emerged when historians, journalists, and archivists began to look again at the experiences of German women held in custody during the final months of the Second World War and the unstable period that followed. It does so carefully, avoiding graphic language and focusing instead on patterns, power, and the long shadow cast by silence.

What follows is not a trial. It is an examination of how stories survive when they are not allowed to be spoken, and how history changes when we finally listen.

Victory, Chaos, and the Blind Spots of Memory

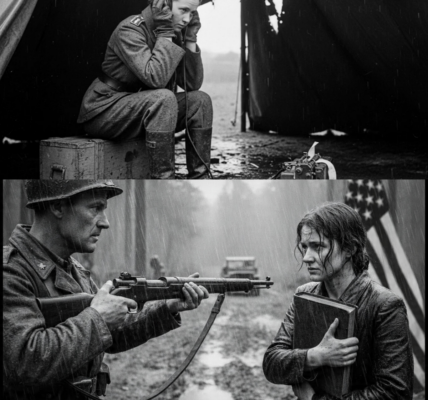

When the war in Europe ended, the public story was clear. Liberation had arrived. Order would be restored. Justice would follow. In that powerful narrative, there was little room for complexity. The world wanted clean lines between right and wrong, hero and villain, liberator and defeated.

But history rarely moves in straight lines.

The final months of the conflict and the early postwar period were marked by disorder. Cities lay in ruins. Command structures shifted overnight. Millions were displaced. Detention centers, temporary camps, and improvised holding facilities appeared across defeated territory. In this environment, oversight was uneven, records were incomplete, and accountability often depended on who was watching.

For women taken into custody under various suspicions, ranging from political involvement to simple association, the experience could be deeply isolating. They were surrounded by authority but often without advocates. Many were young. Many were alone. And many understood very quickly that silence was safer than speaking.

The victorious side wrote the reports. The defeated learned to endure.

The Language of Pain Without Words

One of the most striking features of the surviving testimonies is what they do not say. Instead of direct descriptions, there are references to discomfort, to changes in posture, to long periods of illness without clear cause. Doctors’ notes from years later mention chronic pain, difficulties with movement, and conditions that began “during detention” without further explanation.

“I could not sit for long,” one woman said in a recorded interview in the 1970s. “I learned to stand, even when tired.”

Another recalled avoiding public transport because of the pain of hard seats. A third spoke of sewing cushions by hand, not as decoration but as necessity.

These statements, taken alone, could mean many things. Taken together, across regions and decades, they form a pattern that is difficult to ignore.

Historians refer to this as indirect testimony: when survivors communicate experience through consequence rather than description. It is a language shaped by fear, shame, and the knowledge that some truths were not welcome in the world they returned to.

Custody Without Clarity

Detention during and after the war took many forms. Some women were held for questioning. Others were transferred between facilities as borders and authorities changed. The legal status of these detainees was often unclear, and procedures varied widely.

In some locations, oversight was strict and documented. In others, authority rested with small units far from higher command. The difference mattered.

Archival fragments show that complaints were rare and, when made, often dismissed as unreliable. The assumption of moral superiority on the part of the victors made it easy to ignore uncomfortable claims. After all, how could those who had defeated a brutal regime be capable of wrongdoing themselves?

This question, once unthinkable, now sits at the center of modern historical debate.

Why So Few Spoke, and Why Many Never Did

To understand the silence, one must understand the cost of breaking it.

For German women after the war, life was already marked by loss. Homes destroyed. Families separated. Hunger and uncertainty were constant companions. To speak openly about mistreatment in custody risked social isolation, disbelief, and retaliation in a world where survival depended on cooperation with occupying authorities.

There was also the burden of collective guilt. Many women felt that any personal suffering would be dismissed or even condemned as deserved, simply because of nationality. This belief, reinforced by the political climate of the time, kept mouths closed and memories private.

Some tried to speak years later, only to find that the world had moved on. Others shared their stories only within families, often in fragments, often late in life.

“It was not something you put on paper,” one daughter recalled her mother saying. “It was something you carried.”

The Archivists Who Noticed the Gaps

In the late twentieth century, a new generation of researchers began to notice inconsistencies in postwar records. Medical files referenced injuries without recorded causes. Welfare applications mentioned trauma linked to detention but lacked detail. Oral histories contained repeated phrases that seemed almost coded.

At first, these details were dismissed as coincidence. But as collections grew and technology allowed wider comparison, the patterns became harder to explain away.

Researchers began cross-referencing personal letters, local clinic records, and interviews recorded decades apart. The same themes appeared again and again: pain when sitting, fear of uniforms long after the war, a reluctance to enter official buildings.

None of this proved a single event. But history is rarely built on single events. It is built on accumulation.

Power, Vulnerability, and the Absence of Witnesses

One reason these stories remained hidden for so long lies in the imbalance of power. Detention settings place individuals in total dependence on authority. When that authority is armed, foreign, and unaccountable, vulnerability increases dramatically.

In such environments, witnesses are rare. Those present may fear consequences. Records, if kept, may be incomplete or later destroyed. What remains is memory, and memory is often treated as unreliable, especially when it challenges comforting narratives.

Yet modern historical method recognizes that memory, when consistent across independent sources, is evidence of a different kind. Not courtroom proof, but human truth.

How Language Was Used to Erase Experience

Another barrier to understanding lies in the language of official documentation. Reports often used neutral terms that concealed lived reality. Transfers, interrogations, and “disciplinary measures” could encompass a wide range of experiences, yet the words themselves revealed nothing.

For the women involved, this bureaucratic language added a second layer of erasure. Not only were their experiences undocumented, but the words used ensured that even if documents survived, they would say very little.

This gap between lived experience and recorded history is where investigative journalism now operates, carefully, respectfully, and with an awareness of past harm.

Families, Inheritance, and Silent Echoes

The impact of these hidden experiences did not end with those who lived through them. Children and grandchildren grew up sensing something unspoken. They noticed habits, fears, and unexplained illnesses.

Some remembered being told not to ask questions. Others recalled emotional distance or sudden anger triggered by sounds, uniforms, or authority figures. These family memories, once dismissed as anecdotal, are now recognized as part of the historical record.

Trauma does not require explicit storytelling to be passed on. Sometimes it travels through silence.

Why This History Matters Now

In recent years, societies around the world have begun to reexamine the moral simplicity of past conflicts. This is not about rewriting victory or denying the crimes of defeated regimes. It is about acknowledging that human behavior does not become pure simply because the cause is just.

Recognizing hidden suffering does not weaken historical truth. It strengthens it.

For survivors who are still alive, acknowledgment offers a form of dignity long denied. For those who are gone, it offers something else: the assurance that their pain was not invisible after all.

The Careful Line Between Exposure and Respect

Writing about these topics requires restraint. Sensational language can cause harm, retraumatize families, and reduce complex lives to headlines. That is why this article avoids explicit description and focuses instead on structures, patterns, and consequences.

The goal is not shock for its own sake, but understanding. Curiosity should lead to empathy, not exploitation.

What We Still Do Not Know

Many questions remain unanswered. Records are missing. Witnesses are gone. Some truths may never be fully documented. History, unlike fiction, does not always offer closure.

But uncertainty is not the same as ignorance. The accumulation of testimony, however indirect, demands attention.

When multiple women, unknown to one another, describe the same long-term pain linked to the same period of custody, history is speaking quietly but clearly.

Listening to the Sentence Again

“It hurt when I sat down.”

Heard once, it might seem trivial. Heard in isolation, it might be dismissed. Heard across decades, regions, and archives, it becomes something else entirely.

It becomes a reminder that the end of war is not the end of consequence, that victory can carry shadows, and that silence is often the final chapter written by those with the least power.

History is not only what was shouted from podiums. It is also what was whispered at kitchen tables, carried in bodies, and finally, carefully, brought into the light.

And once heard, it cannot be unheard.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.