‘My Hands Used to Play Piano’ — German POW Woman Whispered Looking at Her Scarred Fingers. NU.

‘My Hands Used to Play Piano’ — German POW Woman Whispered Looking at Her Scarred Fingers

THE HANDS THAT STILL KNEW MUSIC

A World War II Story

Chapter I – Arrival Under a Vast Sky (Texas, 1945)

Texas, March 1945.

The mess hall at Camp Swift fell silent as the women entered.

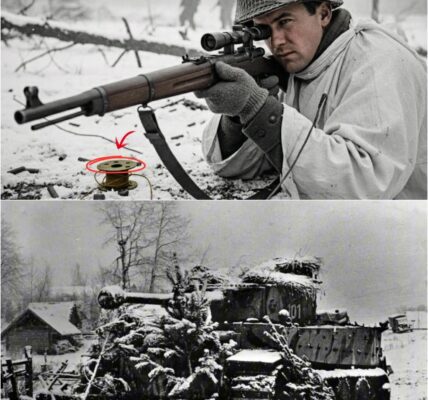

Twelve German prisoners stood beneath the humming fluorescent lights, their gray dresses hanging loosely from bodies thinned by years of deprivation. The air smelled of dust and metal, of boiled food and military order. American guards paused in their routines—not out of hostility, but curiosity. These women did not look like enemies. They looked like survivors who had reached the edge of endurance.

One woman lingered near the entrance. She was smaller than the others, her posture careful, almost guarded. Her hands were held close to her body, fingers bent inward as if protecting something invisible. Her eyes, however, were fixed on the far corner of the hall.

There stood a piano.

It was an upright instrument, dark wood, its surface covered with a cloth dulled by dust. It had likely been placed there for soldiers’ recreation—for hymns, for popular songs, for moments of relief from the weight of war. Now it sat unused, forgotten.

The woman’s lips moved, silently.

Later, a guard would remember what she whispered.

“My hands used to play piano.”

Her name was Lisa Hartman.

Outside, Camp Swift stretched across central Texas, its barracks and parade grounds set beneath a sky so wide it seemed to swallow human concerns whole. Guard towers cast long shadows. Beyond the wire, cattle moved slowly through dry grass, unconcerned with uniforms or flags. The war felt distant here, abstract, as if it belonged to another world.

Colonel James Morrison, the camp commander, reviewed the women’s files with practiced efficiency. He was a career officer who believed deeply in order, discipline, and the obligations set forth by the Geneva Conventions. He had seen enough of war’s consequences to know that cruelty did not strengthen victory—it corrupted it.

Lisa Hartman’s file was thin.

Born in Dresden, 1914.

Educated at the Dresden Conservatory.

Concert pianist.

Arrested in 1943.

“Injuries sustained during internment.”

Nothing more.

Morrison closed the folder and stared out the window at the endless land beyond the camp. He wondered what these women thought of such openness, after years behind walls.

Chapter II – The Scars That Told the Truth

The women were housed in a separate compound—simple wooden barracks surrounded by fencing, but with windows that opened. Air moved freely. Sunlight entered without permission.

For many of them, this alone felt unreal.

Lisa took a lower bunk near the door. She moved carefully, deliberately, as if her body had learned that sudden movement could invite pain. Her hands remained folded in her lap, fingers curled inward.

At dinner, the food was plentiful: mashed potatoes, vegetables, real meat. No one shouted. No one struck them. The guards stood back, watchful but restrained.

Lisa barely ate. Her gaze never left the piano.

The following morning, work assignments were given. Some women went to the kitchens or laundry. Lisa was sent to the camp library.

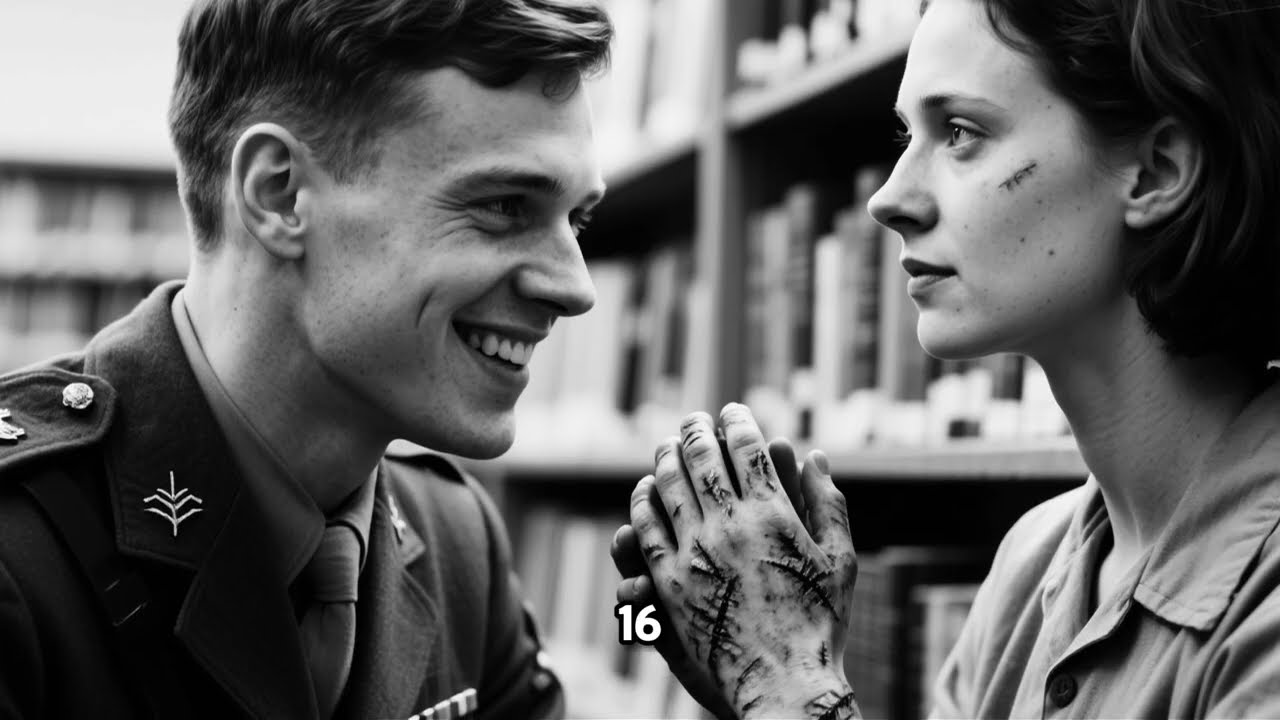

The librarian, Corporal Daniel Reeves, was twenty-three, bespectacled, and gentle in manner. Before the war, he had studied library science. The Army had decided his skills were better used preserving knowledge than carrying a rifle.

He showed Lisa how to shelve books, speaking slowly, clearly. She worked in silence, her scarred fingers moving carefully along the spines. Dust floated in the sunlight. Outside, soldiers called to one another across the parade ground.

For the first time in years, her body loosened slightly.

On the third day, Reeves placed a folder on the desk without comment.

Sheet music.

Chopin nocturnes.

Lisa stared at it for a long time before opening it. Her hands began to tremble. She could no longer hear music the way she once had—something inside her had been damaged by pain and fear—but she could still read it. She could remember.

Tears fell quietly onto the yellowed pages.

The camp doctor, Dr. Elizabeth Chun, examined Lisa later that week. She was an experienced physician, professional and composed, yet deeply observant.

When Lisa extended her hands, the truth was unmistakable.

Burns. Cuts. Crushed bones that had healed improperly. Skin thick and rigid, fingers bent at wrong angles. These were not accidents. They were deliberate.

“What happened?” Dr. Chun asked softly.

Lisa hesitated, then spoke in careful English.

“I helped someone escape. A student. After a concert.”

She gestured toward her hands.

Dr. Chun understood. This was not random violence. This was punishment meant to erase identity.

“I’m sorry,” she said—and meant it.

Chapter III – Kindness Without Conditions

Weeks passed. No cruelty came.

For Lisa, this absence was unsettling. She waited for punishment that never arrived. The American guards followed rules, not whims. They did their duty without humiliation or excess.

This restraint—this quiet professionalism—was not something she had known before.

Reeves continued bringing sheet music. Beethoven. Mozart. Brahms. Debussy. He never asked questions. He never demanded gratitude.

One afternoon, he finally spoke.

“I heard you once,” he said. “Before the war. In San Antonio.”

Lisa looked up, startled.

“You played Rachmaninoff. I was sixteen. I didn’t understand music then. You changed that.”

She shook her head slowly. “That was another person.”

“Maybe,” Reeves replied. “But she existed.”

The war in Europe ended in May. News arrived slowly, filtered through routine. Relief mixed with uncertainty. Letters from home spoke of ruined cities and vanished families.

Lisa received none.

She continued her work in the library. Reading. Remembering.

And then came the announcement.

A concert. July Fourth. A celebration of peace.

Lisa attended as a listener only. The piano had been cleaned, tuned. Soldiers and prisoners sat side by side.

When Reeves took the bench, he looked directly at her.

“This is for someone who taught me what music means,” he said.

He played Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C minor.

The sound struck Lisa with physical force.

She remembered not only the music, but the feeling of playing it—the resistance of keys, the weight of sound moving through her hands.

She left before the applause ended.

Reeves found her later, standing by the fence, staring at the vast Texas sky.

“I thought it was gone,” she said. “All of it.”

“They destroyed how you played,” he answered gently. “Not what you knew.”

Chapter IV – The First Note

The next morning, Lisa asked for permission to use the piano.

Colonel Morrison agreed without hesitation.

She sat at the bench for days without touching the keys. Simply sitting. Remembering. Mourning.

Then, one afternoon, she pressed a single note.

Middle C.

Clear. Honest. Unjudging.

She pressed it again.

The sound did not care about scars.

She played a scale, slowly, painfully. It was not performance. It was contact.

Reeves listened from a distance, saying nothing.

Soon, she began to write—technique, theory, teaching notes. Other prisoners watched. One asked for lessons.

Then another.

Lisa discovered that although her hands were limited, her knowledge was intact.

Dr. Chun observed one lesson and spoke to her afterward.

“What was done to you was meant to destroy you,” she said. “Every time you teach, you prove they failed.”

Chapter V – A New Purpose

By late summer, Lisa had several students. She taught with discipline and kindness, the same standards she once demanded of herself.

When repatriation lists were posted, her name appeared for October.

Colonel Morrison called her to his office.

“There is a program in Germany,” he said. “Rebuilding education. They need teachers.”

He slid the application across the desk.

“You would be perfect.”

Lisa hesitated. Then she remembered the first note. The scale. The students.

She applied.

Approval came in September.

She would teach in Frankfurt.

On her final night at Camp Swift, she played what she could. Simple melodies. Honest ones.

The scars remained. But they no longer defined her.

Chapter VI – What Survived

Lisa Hartman taught music in Frankfurt for thirty-two years.

She never performed publicly again. But her students numbered in the hundreds—then thousands. Some became musicians. Others became teachers.

In 1967, a concert was dedicated to her.

Afterward, someone asked how she learned to teach despite her injuries.

She looked at her hands.

“In Texas,” she said, “I learned that what they took from my hands, they could not take from my understanding.”

Her story became one of survival, dignity, and quiet courage.

And the music played on.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.