Why Americans Attacked While Allies Took Cover ?

At 11:30 hours on December 22nd, 1944, four German officers approached the American lines outside Bastoni, Belgium, carrying a white flag. They brought a formal surrender ultimatum from General Henrik Fonlutvitz, commander of the 47th Panza Corps. The message was direct. The American position was hopeless. Surrounded by seven German divisions, no chance of relief, limited ammunition and supplies.

Surrender now with honor or face annihilation by German artillery and armor. The ultimatum was delivered to Brigadier General Anthony Clement McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division. McAuliffe had been napping when his staff woke him with the German demand. He read it, looked at his officers, and said one word, nuts.

His staff thought this was his initial reaction, not his formal response. But Mclliff insisted. That was his official reply. Nuts. Send it back to the Germans exactly as stated. Lieutenant Colonel Harry Kard typed the response to the German commander. Nuts. The American commander. Colonel Joseph Harper delivered it personally.

When the confused German officers asked what the word meant, Harper explained in clear terms, “It means the same as go to hell.” In plain English, it means no. McAuliff’s one-word response captured something fundamental about American military doctrine that had been developing for more than two decades. Something that made American forces fight differently than any other army in the Second World War.

When surrounded, most armies defended and waited for rescue. Americans counterattacked. This difference in tactical philosophy did not happen by accident. It was the result of deliberate choices made by military leaders who studied the First World War and determined that American forces would never fight that way again. The transformation began on September the 1st, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland.

That same day, General George Catlet Marshall was sworn in as chief of staff of the United States Army. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had passed over 33 more senior generals to select Marshall, a decision that shocked the military establishment. Marshall inherited an army that ranked 17th in the world.

174,000 soldiers scattered across 130 posts and stations worldwide, smaller than the armies of Portugal, Romania, and Spain. Most units were under strength. Equipment dated from the First World War. Training was minimal and focused primarily on garrison duties and ceremonial functions. The United States Army in 1939 resembled a constabularary force more than a modern combat organization.

Officers spent more time on paperwork than tactical training. Mying Enlisted men performed administrative duties, construction projects, and guard details. Large-cale maneuvers were rare. Combined arms training was almost non-existent. The idea that this small, scattered force would need to fight a major war seemed remote.

But Marshall had seen modern war firsthand. He had served in France during the First World War as a staff officer with the American Expeditionary Forces. He had planned major operations, including the Muse Argon offensive, which involved moving more than half a million soldiers into position for the largest battle in American history.

He had watched American units take massive casualties in frontal attacks against prepared German positions. He had seen talented officers fail because they could not adapt to rapidly changing battlefield conditions. He had witnessed the consequences of rigid centralized command structures that could not respond fast enough to tactical realities.

Marshall understood that the next war would be even more complex, more mobile, and more deadly than the last. American forces would need to be trained differently. They would need doctrine that emphasized flexibility, initiative, and aggressive action rather than rigid adherence to plans that became obsolete the moment combat began.

The foundation for this new doctrine had been laid years earlier at Fort Benning, Georgia. From November 1927 to June 1932, Marshall served as assistant commandant of the infantry school at Fort Benning. During those four and a half years, he revolutionized how the United States Army trained its infantry officers.

200 future generals passed through Fort Benning as students or instructors during Marshall’s tenure, including Omar Nelson Bradley, Joseph Warren Stillwell, Matthew Bunker Rididgeway, and Walter Bedell Smith. Marshall’s approach was radical for its time. He stripped away the complex formal tactical problems that had dominated military education and replaced them with simple practical exercises focused on making rapid decisions with incomplete information.

He told instructors that officers needed to learn how to think, not what to think. He emphasized that in combat there would never be perfect information, never enough time, never ideal conditions. Officers had to be trained to act decisively despite uncertainty. Traditional military education at thetime emphasized following established procedures and waiting for orders from higher headquarters.

Marshall taught the opposite. He wanted officers who would take initiative, make decisions based on their assessment of the situation, and act without waiting for permission. He told students that it was better to make a decision and execute it immediately than to wait for perfect conditions that would never come.

Marshall’s tactical philosophy centered on offensive action. He taught that the best defense was a good offense. When a unit was attacked, the immediate response should be to counterattack. Do not wait to assess the full situation. Do not wait for reinforcements. Do not wait for orders from higher headquarters.

Identify where the enemy is. Fix them in place with fire and assault their position before they can consolidate their gains. This emphasis on immediate counterattack was based on Marshall’s analysis of First World War combat. He had observed that German forces were most vulnerable immediately after an attack when they were disorganized, low on ammunition, and uncertain about American strength and dispositions.

If American forces counteract attacked immediately, they could often retake lost positions before the Germans could consolidate. But if American forces waited, the Germans would bring up reinforcements, establish defensive positions, and sight their machine guns. What could have been retaken in minutes would require hours of costly fighting.

Marshall also observed that American officers in the First World War often failed not because they lacked courage or tactical knowledge, but because they could not make decisions quickly under pressure. Officers who had been trained to follow detailed procedures and wait for orders from higher headquarters became paralyzed when communications broke down or when the tactical situation changed faster than orders could be transmitted.

To address this problem, Marshall fundamentally changed how Fort Benning trained officers. He eliminated the practice of giving students problems with detailed scenario information and days to prepare solutions. Instead, he gave officers minimal information, imposed tight time limits, and evaluated them on their ability to make rapid decisions and issue clear orders.

One of Marshall’s signature training innovations was the tactical walk. Officers would be taken into the field with no advanced warning of what they would encounter. At various points during the walk, an instructor would say, “Your unit is here. The enemy is reported in this direction. What are your orders? The officer had 5 minutes to assess the terrain, determine a course of action, and issue verbal orders to an imaginary unit.

Then the walk would continue, and another problem would be presented. This training was designed to simulate the confusion and time pressure of actual combat. Officers could not prepare elaborate written orders. They had to think quickly, decide rapidly, and communicate clearly under pressure. The training emphasized that in combat, a good decision executed immediately was better than a perfect decision that came too late.

Marshall also changed how officers were evaluated. Traditional military education emphasized knowledge of regulations and procedures. Students who could quote field manuals and recite proper forms received high marks. Marshall emphasized practical execution. Students who could make sound tactical decisions under pressure and lead soldiers effectively received high marks even if they could not quote regulations perfectly.

This shift from procedural knowledge to practical judgment was revolutionary. It meant that officers were being trained to think rather than simply follow procedures. It meant that junior officers were expected to exercise judgment and take initiative rather than simply execute orders exactly as given. The impact of these training reforms extended beyond the officers who passed through Fort Benning.

The officers Marshall trained became instructors at other schools and commanders of training units. They spread marshalls methods throughout the army. By the late 1930s, officer training across the United States Army had shifted toward emphasizing initiative, rapid decision-making, and aggressive action. Marshall also revolutionized training methods.

He eliminated lengthy lectures and replaced them with outdoor practical exercises. Officers spent most of their time in the field solving tactical problems under time pressure with limited resources. Marshall wanted training to be as realistic and stressful as possible so that when officers faced actual combat, they would already be accustomed to operating under pressure.

The results of Marshall’s reforms at Fort Benning would not become fully apparent until the Second World War when the officers he trained became the commanders who led American forces to victory. But the principles he established became the foundation of American tacticaldoctrine.

When Marshall became chief of staff in 1939, he immediately began implementing these principles across the entire army. Marshall understood that the United States would likely be drawn into the war in Europe. He also understood that American forces were completely unprepared. Building an effective army would require more than just buying equipment and recruiting soldiers.

It would require changing how the army thought about warfare and how it trained its soldiers and officers. Marshall’s first priority was identifying and promoting officers who shared his vision of mobile aggressive warfare. He was ruthless in removing officers who could not adapt. Marshall later estimated that he relieved or forced into retirement more than 600 officers before American forces even entered combat overseas.

This included generals, colonels, and senior staff officers who had spent decades in the army. Marshall’s critics accused him of destroying the officer corps. Marshall believed he was saving it from obsolescence. The officers Marshall promoted were younger, more aggressive, and more willing to challenge conventional thinking.

Men like George Smith Patton Jr., who shared Marshall’s belief in speed and offensive action. Men like Dwight David Eisenhower who understood how to coordinate complex operations across multiple services and nationalities. Men like Jacob Luke’s devs who pushed for mechanization and modernization. These were officers who would implement Marshall’s doctrine of aggressive mobile warfare.

Marshall’s second priority was training. The army needed to grow from less than 200,000 soldiers to millions. How those millions were trained would determine whether they survived combat and accomplished their missions. In 1940 and 1941, the United States Army conducted a series of massive training exercises called the Louisiana Maneuvers.

Over 470,000 soldiers participated, making it the largest peacetime military exercise in American history. Entire divisions maneuvered across Louisiana and East Texas, practicing offensive and defensive operations, river crossings, airground coordination, and rapid movement over long distances. The maneuvers divided forces into two opposing armies, red and blue, that fought each other using all available equipment and tactics.

The exercises covered more than 3,000 square miles of territory and lasted for several months. Local civilians found themselves hosting the largest military operation ever conducted on American soil. Soldiers camped in fields, towns hosted headquarters units, and the Louisiana economy experienced a massive influx of military personnel and equipment.

Marshall attended the Louisiana maneuvers personally and watched carefully. He was testing whether his doctrinal concepts would work at scale. Could large units move quickly and maintain offensive momentum? Could junior officers make decisions and take initiative without waiting for detailed orders from higher headquarters? Could soldiers adapt to rapidly changing situations? The maneuvers confirmed Marshall’s beliefs.

Units that moved aggressively and counterattacked immediately when hit performed better than units that waited for orders and tried to fight defensively. Junior officers who took initiative without waiting for direction from higher headquarters achieved better results than those who hesitated. Small units that maneuvered independently and attacked enemy flanks disrupted larger enemy formations more effectively than frontal assaults with superior numbers.

One notable example involved a young tank officer named Dwight Eisenhower serving with the Third Army during the maneuvers. Eisenhower demonstrated how armored units could bypass enemy strong points and strike deep into rear areas to disrupt command and control. His aggressive tactics confused the opposing force and demonstrated the potential of mobile armored warfare.

Marshall noted Eisenhower’s performance and later promoted him rapidly through the ranks. Another officer who distinguished himself was George Patton, commanding an armored division. Patton pushed his units to move faster and farther than maneuver plans called for. At one point, he drove his tanks through civilian areas that were technically outside the maneuver boundaries, arguing that in real war, there would be no boundaries.

Umpires complained about Patton’s disregard for rules. Marshall saw it as evidence of exactly the kind of aggressive mindset American commanders would need. The maneuvers also revealed weaknesses that needed to be addressed. American units struggled with logistics. Supply lines were often disorganized with units running out of fuel or ammunition because supply officers could not keep track of rapidly moving formations.

Communications between units were unreliable with radio nets breaking down and messages being lost or delayed. Coordination between infantry, armor, and artillery was poor, with supporting fires often arriving too late or hittingthe wrong locations. But these were problems that could be fixed through better training, improved equipment, and refined procedures.

The fundamental tactical concepts were sound. Aggressive offensive action worked. Decentralized decision-making worked. Rapid movement and exploitation worked. American doctrine was on the right track. By December 1941, when the United States entered the war after Pearl Harbor, the army had grown to more than 1.6 million soldiers.

More importantly, those soldiers were being trained according to Marshall’s doctrine of aggressive offensive warfare. The doctrine was codified in Field Manual 105, Operations, published in 1941. The manual stated clearly that offense was the decisive form of combat. Defense was temporary, used only to economize force in one area while attacking in another or to gain time before resuming the offensive.

The manual emphasized that when defending, units should conduct aggressive counterattacks to disrupt enemy attacks and regain lost ground. This was fundamentally different from Allied doctrine. The British army had spent two decades perfecting defensive tactics based on their first World War experience. British doctrine emphasized establishing strong defensive positions with mutually supporting fields of fire.

When attacked, British units would hold their ground, call for artillery support, and wait for reserves to be organized for a deliberate, carefully planned counterattack. This deliberate approach took time, hours, sometimes days. British commanders believed that hasty, uncoordinated counterattacks would result in unnecessary casualties against prepared German positions.

The French military had similar doctrine. They emphasized defense in depth with strong points that would channel attackers into killing zones covered by artillery and machine gun fire. French doctrine called for methodical step-by-step operations with overwhelming firepower preparation before any attack. Speed was less important than thorough preparation and coordination.

Soviet doctrine was different, but also emphasized mass and preparation. The Red Army called for massive artillery barges before any offensive operation. Overwhelming force concentrated at decisive points and centralized control from higher headquarters. Soviet counterattacks involved thousands of tanks and hundreds of thousands of soldiers moving according to detailed plans coordinated at army level.

American doctrine was unique among the major powers. It emphasized immediate action by the forces in contact. If a position was threatened, the unit commander on the spot, whether a sergeant, lieutenant, or captain, was expected to counterattack immediately with whatever forces were available. Do not wait for orders from higher headquarters.

Do not wait for reinforcements. Do not wait for perfect information about enemy strength and positions. Attack now with what you have before the enemy can consolidate their gains. This doctrine required a different kind of soldier than other armies produced. American training focused on creating soldiers who could think and act independently, who understood the commander’s intent rather than just following specific orders, who could adapt to unexpected situations without waiting for direction.

At infantry replacement training centers across the United States, recruits spent 13 weeks learning to be soldiers. A substantial portion of that training focused on battle drills that emphasized aggressive action. React to ambush, assault a fortified position, conduct a hasty attack, clear a building. Every drill emphasized immediate offensive action.

The training was physically exhausting and mentally demanding. Recruits marched 20th separately assaulted an objective. They dug fox holes, then got ordered to abandon them and attack in a different direction. They learned that there was no time to rest, no time to wait for perfect conditions, no time to get every detail right.

You acted with what you had when you could. Officer training at Fort Benning was even more intensive. The infantry officer candidate school compressed the equivalent of four years of college level military education into three months. Candidates were constantly evaluated on their ability to make rapid decisions under pressure, to lead soldiers in realistic tactical exercises and to adapt to unexpected changes in the tactical situation.

Instructors created scenarios where there was no perfect solution, no time to gather all relevant information, no opportunity to coordinate properly with adjacent units. Young officers had to make decisions with incomplete information and accept the consequences. The training was designed to produce officers who would take initiative and accept risk rather than waiting for guidance from higher headquarters.

This training philosophy produced a distinct American tactical culture. Junior leaders were expected to show initiative. A lieutenant who saw anopportunity to attack was expected to do so even if it meant deviating from the original plan. A captain who found the enemy flank exposed was expected to attack immediately rather than report up the chain of command and wait for orders.

The culture was reinforced by Marshall’s personnel policies. Officers who showed initiative and achieved results were promoted rapidly regardless of seniority. Officers who waited for orders and avoided risk were relieved of command. Marshall made it clear that in the American army, aggressive action would be rewarded and timidity would be punished.

The first real test of American doctrine came in North Africa in February 1943. The battle of Casarine Pass was the first major engagement between American and German forces. German armor under Field Marshal Irwin Raml attacked American positions in Tunisia on February 14th. The attack achieved complete tactical surprise.

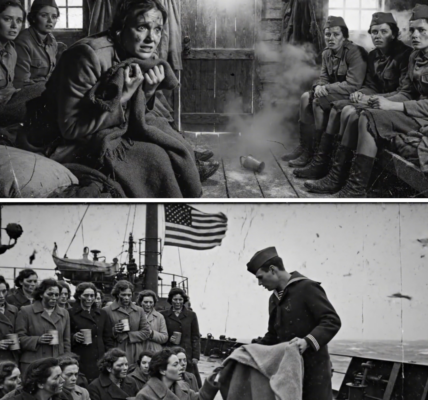

American units, most of which had never been in combat, were scattered and driven back 50 mer. By February 20th, the situation looked desperate. American forces had suffered more than 6,000 casualties, including 3,000 soldiers missing or captured. Equipment losses were heavy. Unit cohesion had broken down in many areas.

British commanders expected the Americans to pull back, reorganize, and prepare a deliberate counteroffensive. That was how the British would have responded after such a defeat. Take time to assess what went wrong, reorganize units, wait for replacements, and resupply. Plan the next operation carefully to avoid repeating mistakes.

American forces did not wait. Within 24 hours of the worst fighting, American artillery units that had retreated in disorder were back in action, firing in support of infantry counterattacks. Tank units were refueling and rearming, ready to engage again. Infantry regiments that had been scattered were reforming and moving back toward the enemy.

By February 22nd, just 3 days after the peak of the German assault, American counterattacks had stopped the German advance. By February 24th, American forces had recaptured all the territory they had lost. The Germans withdrew, having failed to achieve their operational objectives. British commanders were both impressed and appalled.

Impressed by American resilience and aggressive spirit, appalled by what they saw as reckless haste and poor coordination, British doctrine said you needed weeks to recover from a defeat like Karine Pass. The Americans recovered in days. General Harold Alexander, the British officer who took overall command after Cassarine Pass, tried to slow the Americans down.

He wanted them to wait, train more, and conduct more methodical operations. But American commanders pushed for immediate action. General George Patton, who took command of second corps after Cassin Pass, told his officers that the way to recover from a defeat was to attack immediately. Make the enemy worry about what you are going to do to them, not what they are going to do to you.

Within a month, American forces won the battle of Elgetta, their first clear tactical victory against the Vermacht. The aggressive doctrine was working. By June 1944, when Allied forces landed in Normandy, American tactical doctrine had been refined through campaigns in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy.

Junior officers knew to take initiative. Soldiers knew to counterattack immediately when hit. The culture of aggressive offense was deeply embedded at all levels. This brings us to December 1944 and the German Ardan offensive. On December 16th, 1944, at 0530 hours, German forces launched the largest offensive they would mount in the West during the entire war.

30 divisions, 250,000 men, nearly 1,000 tanks, and assault guns. The attack achieved complete tactical surprise along an 85 mm front in the Ardan forest of Belgium and Luxembourg. Weather conditions favored the Germans. Heavy snow, freezing temperatures, dense fog that grounded Allied aircraft. German armor advanced rapidly through thinly held American positions.

Some American units broke and ran. Others were surrounded and destroyed. Within 48 hours, German forces had created a bulge 50 m deep into the Allied front. The situation looked catastrophic. American forces were scattered and retreating. German armor was driving toward the Muse River and the vital port of Antworp.

If the Germans reached Antworp, they would split the Allied armies and potentially force a negotiated peace that would allow Germany to continue the war. But three things happened that the Germans did not expect. First, small American units throughout the Ardan immediately began mounting local counterattacks.

At dozens of crossroads and villages, American forces that had been bypassed or surrounded did not surrender or retreat to the rear. They counteratt attacked. These small unit actions bought time. Every hour the Germans were delayed allowed more American forces to move into position.

Every counterattackforced German units to deploy from March column into combat formation, slowing their advance. The cumulative effect of hundreds of small, often unsuccessful counterattacks was to disrupt the German timetable and prevent them from achieving the rapid breakthrough their plan required. Second, American commanders immediately began organizing large-scale counterattacks without waiting for the overall situation to be clear.

Within 24 hours of the initial German attack, General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, was moving entire divisions toward the breakthrough, not to establish defensive positions, but to counterattack. On December 19th, Eisenhower met with his senior commanders at Verdon, France. The meeting began at 1100 hours.

Present were Lieutenant General Omar Bradley commanding 12th Army Group, Lieutenant General Jacob Deis commanding sixth army group, Lieutenant General George Patton commanding third army and senior staff officers. Eisenhower opened the meeting by saying that the present situation should be regarded as one of opportunity for the Allied forces, not disaster.

The Germans had come out of their fortifications. Now they could be attacked and destroyed in the open. He turned to Patton and asked how soon Third Army could counterattack. Patton said he could attack with three divisions in 48 hours. The room went silent. Third army was 100 meter south of the breakthrough.

Fully engaged in offensive operations toward the German border in the S region. To counterattack into the Ardans, Patton would have to disengage from his current offensive, turn his entire army 90° north and attack into the German flank. This required moving hundreds of thousands of men, thousands of vehicles, repositioning artillery, arrooting supply lines, and coordinating with other Allied units.

British and German military planners estimated such a maneuver would take at least two weeks, possibly a month. Moving an entire army required careful planning, detailed logistics, coordination, and methodical execution. You could not just turn an army 90 degra and attack in 48 hours. It was tactically impossible.

Eisenhower looked skeptical. Do not be fatuous, George, he said. He ordered Patton to attack with three divisions on December 22nd, giving him 72 hours instead of 48. What Eisenhower did not know was that Patton had anticipated this request. Before leaving for Verden, Patton had ordered his staff to prepare three contingency plans for turning north.

The plans were cenamed nickel, dime, and cent corresponding to different axes of advance. When Eisenhower gave the order, Patton’s staff simply executed the plan they had already prepared. But executing the plan still required extraordinary effort and coordination. Third Army staff officers worked through the night, issuing orders.

Regimental commanders disengaged from their current operations and began moving north. Battalion commanders organized their units for movement while still in contact with the enemy. Company commanders rued supply convoys on their own initiative. Supply officers worked through the night, establishing new logistics routes.

Artillery units displaced their guns, moved north, and prepared to fire in support of the counterattack. Nobody waited to be told exactly what to do. They knew the mission. Attack north. They figured out the details themselves. This was exactly what Marshall’s training doctrine was designed to produce. junior leaders who could execute complex operations without detailed direction from higher headquarters.

At 0630 hours on December 22nd, 66 hours after the Verdon meeting, three divisions of third army attacked north into the German flank. Fourth armored division led the advance, driving toward Bastonia, where American forces had been surrounded since December 20th. The defense of Bastonia itself demonstrated American tactical doctrine in action.

Bastonia was a small Belgian town that controlled seven roads converging from different directions. Whoever controlled Bastonia controlled movement throughout the region. The Germans needed those roads for their offensive. They had to capture Bastonia or their advance would stall. American forces defending. Bastonia included the 101st Airborne Division, Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division, and various support units.

Total strength was approximately 15,000 men. They were surrounded by seven German divisions, totaling more than 45,000 soldiers with heavy armor and artillery support. The conventional military response to being surrounded was to establish a defensive perimeter and wait for relief. Conserve ammunition, avoid unnecessary engagements, hold the line until help arrived.

American forces in Baston did the opposite. They attacked. Throughout the siege, American forces conducted continuous offensive operations. When German forces probed the defensive perimeter, American units did not just repel the attack. They counterattacked to push the Germans backand inflict casualties. When German artillery positions were located, American units organized raids to attack them.

When German infantry attempted to infiltrate the lines, American patrols went out to hunt them down. The aggressive counterattack doctrine was practiced by soldiers throughout the Bastonia perimeter. When German forces attempted to breach American lines, the response was always the same. Immediate counterattack.

On December 23rd, German infantry from the 26th Vulks Grenadier Division penetrated American positions near the village of Marvy on the southeastern edge of the perimeter. The penetration threatened to split the American defense and allow German armor to enter Baston from the east. Team O’Hara from Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James O’Hara immediately counterattacked.

The team included M4 Sherman tanks, M5 Stewart light tanks, M18 Hellcat tank destroyers, armored infantry and halftracks, and supporting engineers. They did not wait for orders from higher headquarters. They did not wait to assess German strength. They attacked immediately. The counterattack hit German infantry who were attempting to consolidate their penetration.

American tanks rolled through German positions, firing high explosive and machine gun rounds. Armored infantry dismounted and cleared buildings. Engineers blew up German strong points with demolition charges. The fighting was close and brutal. American and German soldiers fought roomto- room in Marvy village, but within two hours, American forces had driven the Germans back and reestablished the original defensive line.

Similar actions occurred around the entire Bastier perimeter. On the northern sector, the 56th Parachute Infantry Regiment conducted night raids against German positions. On the western sector, the 52nd Parachute Infantry Regiment attacked German artillery observation posts. On the southern sector, glider infantry from the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment ambushed German supply columns.

These were not isolated incidents. They were consistent application of doctrine. Every commander from battalion to squad level understood that when Germans attacked, the response was immediate counterattack. This kept German forces off balance and prevented them from massing overwhelming force at any single point. The defenders also benefited from artillery support that was aggressively employed.

American artillery doctrine emphasized massing fires quickly and shifting targets rapidly. When German forces were spotted concentrating for an attack, American artillery would hit them with concentrated fire before they could assault. When German infantry attacked American positions, artillery would fire directly in front of American lines, so close that shell fragments sometimes wounded American soldiers.

This was acceptable. Better to take some friendly casualties from your own artillery than to be overrun by German infantry. The 969th Field Artillery Battalion, an all black unit, provided critical fire support throughout the siege. The battalion fired more than 10,000 rounds during the siege, often at danger close range to American positions.

Battery commanders made independent decisions about targets and fire missions without waiting for approval from higher headquarters. This decentralized control allowed artillery to respond immediately to requests from infantry units in contact. American armor also operated aggressively. Tank commanders did not wait in defensive positions for German armor to attack.

They conducted aggressive patrols, engaged German forces at long range, and repositioned constantly to prevent German forces from determining American tank positions. This mobile defense was more effective than static positions would have been, even though it consumed more fuel and wore out equipment faster. The aggressive tactics worked because American soldiers at all levels had been trained to think offensively.

A private manning a machine gun position did not just defend his position. He looked for opportunities to attack German positions with fire. A sergeant commanding a squad did not just hold his section of line. He organized patrols to raid German positions. A lieutenant commanding a platoon did not just wait for orders.

He assessed the situation and took action based on his understanding of the commander’s intent. This tactical culture was the direct result of training that emphasized initiative at all levels. From basic training through advanced individual training through unit training, soldiers learned that they were expected to act, not just follow orders.

When circumstances changed, soldiers were expected to adapt without waiting for new orders. When opportunities appeared, soldiers were expected to exploit them without requesting permission. This was not unusual. It was standard operating procedure throughout the Bastoni defense. Every German attack was met with an immediate American counterattack.

The Germans expected the surrounded Americans to fight defensively, conserving strength and ammunition. Instead, they encountered continuous offensive action that kept German forces off balance and prevented them from massing for a decisive assault. On December 22nd, when the German surrender demand arrived, the American response was not surprising given this tactical culture.

General McAuliff’s one-word reply, nuts, was consistent with the aggressive spirit that pervaded American forces at Bastonia. They were not thinking about surrender or survival. They were thinking about killing Germans. The siege was lifted on December 26th when elements of fourth armored division spearheading Patton’s counterattack reached Bastonia.

Lieutenant Charles Bogus, commanding a tank platoon from company C, 37th tank battalion, led the breakthrough. His lead tank, nicknamed Cobra King, rolled into Baston at 1650 hours. The corridor was only a few hundred yardds wide and came under immediate German fire, but it was enough.

Supplies and reinforcements could reach the defenders. But the relief of Baston did not mean the fighting stopped. American forces immediately transitioned from defense to offense. Units that had been defending the perimeter for six days began attacking outward to expand the corridor and push German forces back. The 101st Airborne Division, which had been surrounded and under constant attack, was conducting offensive operations by December 27th.

German commanders were stunned. How could forces that had just survived a desperate siege immediately go on the attack? Where did they get the supplies? How were they organized so quickly? What kind of soldiers did not need time to recover before resuming combat? The answer was soldiers who had been trained since day one.

That offense was the default. Defense was temporary. Rest came after the enemy was destroyed, not before. This pattern repeated throughout the Battle of the Bulge. American units were hit hard, fell back while counterattacking, reorganized quickly, and resumed offensive operations. There was no long pause for assessment and planning.

The cycle of attack, defend, counterattack, attack again happened in hours, not days. British and Canadian forces fighting in the northern sector of the bulge operated differently. When German attacks were repelled, British units established strong defensive positions and waited for the situation to be clearly assessed before mounting counterattacks.

British commanders organized deliberate, carefully coordinated counteroffensives with proper artillery preparation and clear lines of communication. Both approaches worked, but the American approach was faster. By January 25th, 1945, 41 days after the German offensive began, American forces had eliminated the entire bulge and restored the front line.

German forces had suffered between 85,000 and 100,000 casualties. More critically, they had lost tanks, trucks, artillery, and fuel they could not replace. The Vermacht in the West never recovered from the Battle of the Bulge. American casualties were also heavy. 19,000 killed, 47,000 wounded, 23,000 captured or missing, nearly 90,000 total casualties.

But the Americans had achieved a decisive victory through aggressive continuous offensive action. The tactical principles that saved Bastoni and won the Battle of the Bulge were the same principles Marshall had taught at Fort Benning in the 1920s and codified in army doctrine in the 1940s. Take initiative.

Act decisively with incomplete information. When hit, counterattack immediately. Maintain offensive action. Never give the enemy time to rest and reorganize. After the war ended in May 1945, the United States Army conducted extensive analysis of combat operations. The data confirmed what Marshall and other American commanders had believed.

Aggressive continuous offensive action achieved objectives faster and often with lower cumulative casualties than cautious, methodical approaches. Training that emphasized initiative and speed produced more effective combat units. Doctrine that pushed decision-making to the lowest practical level created more flexible and responsive forces.

These lessons became embedded in American military culture and doctrine through Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, Iraq, and Afghanistan. American military doctrine continued to emphasize offensive action and immediate counterattack. Modern infantry field manuals still teach that the best response to ambush is to assault through the ambush.

Modern officer training still emphasizes making decisions quickly with incomplete information rather than waiting for perfect knowledge. The Marshall Center at Fort Benning, opened in February 2006, teaches these same principles to new generations of Army leaders. The core curriculum emphasizes what Marshall taught in the 1920s.

Offense is the decisive form of warfare. Speed and aggression can overcome superior enemy numbers or positions.Junior leaders must be empowered to act without waiting for direction from higher headquarters. What happened at Bastonia in December 1944 was not an accident or a lucky break. It was the direct result of 20 years of doctrinal development, training, innovation, and cultural change within the United States Army.

The soldiers defending Bastonier fought the way they had been trained to fight since the day they entered the army. When surrounded, they attacked. When offered terms of surrender, they refused. When relieved, they immediately resumed offensive operations. This was not recklessness or bravado. It was doctrine consistently applied.

The difference between American and Allied tactical approaches came down to fundamentally different answers to a basic question. When your forces are under attack, what two do you do? British doctrine said, “Establish strong defensive positions, call for support, wait for the situation to clarify, then launch a carefully planned counterattack with adequate forces and preparation.

Soviet doctrine said, “Mass overwhelming force, coordinate with higher headquarters, prepare with massive artillery bombardment, then attack with numerical superiority.” American doctrine said, “Counter attack immediately with whatever forces you have available before the enemy can consolidate their position.

” All three approaches could work in the right circumstances, but the American approach was consistently faster. And in mobile warfare against a skilled enemy with limited resources, speed often mattered more than perfect preparation. The Germans understood this after fighting American forces for 2 years. German commanders consistently noted in afteraction reports that American forces were the hardest to fight because they never stopped attacking.

When you defeated an American unit, they immediately counterattacked. When you prepared defenses, they attacked before you were ready. When you tried to rest and regroup, they kept the pressure on. The cumulative effect was exhausting and demoralizing for German troops who were already stretched thin and running low on supplies.

German forces on the Eastern Front faced the Soviet Red Army, which employed tactics of overwhelming mass. Soviet offensives involved thousands of tanks, millions of soldiers, and artillery barges that lasted for hours or even days. German forces on the Eastern Front knew when Soviet offensives were coming and could prepare defensive positions.

They could not stop Soviet offensives, but they could channel them and exact heavy casualties. German forces on the Western Front faced American forces that attacked constantly, unpredictably, and with incredible material support. Americans did not mass for one giant offensive. They attacked everywhere all the time with combined arms coordination that Germans could not match.

German commanders never knew where the next American attack would come from or when it would hit. This operational approach was only possible because of three American advantages. industrial production that could supply vast amounts of ammunition, fuel, and equipment. A large population that could replace casualties, and a training system that produced soldiers and officers who could execute complex operations independently without detailed direction from higher headquarters.

Marshall understood all three factors when he designed American tactical doctrine. He knew that American forces would have material advantages that other armies lacked. He designed doctrine to exploit those advantages through continuous aggressive offensive action that consumed resources but maintained constant pressure on the enemy. The doctrine worked.

By May 1945, German forces had been destroyed in both east and west. American ground forces had advanced from Normandy to the Ella River in less than a year. They had destroyed or captured more than 4 million German soldiers. They had done so by attacking continuously, counterattacking immediately when hit and never giving German forces time to rest or reorganize.

General Anthony McAuliffe, who commanded at Baston, retired as a left tenant general in 1956. He was asked many times about his famous nuts reply. He always said the response came naturally. The Germans expected the Americans to be thinking about surrender. The Americans were thinking about how to kill more Germans.

The attitude difference came from training and doctrine that emphasized offensive action regardless of circumstances. General George Patton died in December 1945 from injuries sustained in a car accident in Germany. His rapid relief of Baston became legendary. Moving an entire army 90° and attacking in 66 hours became a case study taught at military mis worldwide as an example of operational agility and aggressive execution.

General Dwight Eisenhower served as Army Chief of Staff after Marshall then became president of the United States. His decision to view the German Ardo offensive as an opportunity rather thana disaster demonstrated how deeply offensive doctrine had penetrated American military thinking at the highest levels.

General George Marshall served as Secretary of State after the war and developed the Marshall Plan for European recovery. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. But his most enduring contribution was the tactical doctrine he developed at Fort Benning in the 1920s and implemented across the United States Army in the 1940s.

That doctrine shaped how American forces fought in the Second World War and continues to shape American military operations today. The principles are simple. Seize the initiative. Maintain offensive action. Counterattack immediately when hit. Empower junior leaders to act without waiting for orders.

Accept risk and uncertainty as inherent in combat operations. Speed and aggression can overcome superior enemy numbers or positions. These principles saved Boston. They won the battle of the bulge. They contributed significantly to Allied victory in Europe and they remain at the core of American military doctrine 75 years later.

That is how military innovation actually happens. Not through advanced technology or overwhelming numbers alone, though both help. Innovation happens through clear thinking about what kind of war you need to fight, what advantages you have, and what doctrine will allow you to exploit those advantages most effectively.

It happens through training systems that instill that doctrine at every level, from private to general. And it happens through leaders who have the courage to implement new approaches even when they contradict conventional military wisdom. If you found this account meaningful, please like this video.

It helps us share more essential chapters from the Second World War. Subscribe to stay connected with these histories. Each story preserves lessons that remain relevant today. Leave a comment telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans continents and generations. United by commitment to understanding how history shapes the present.

See you soon

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.