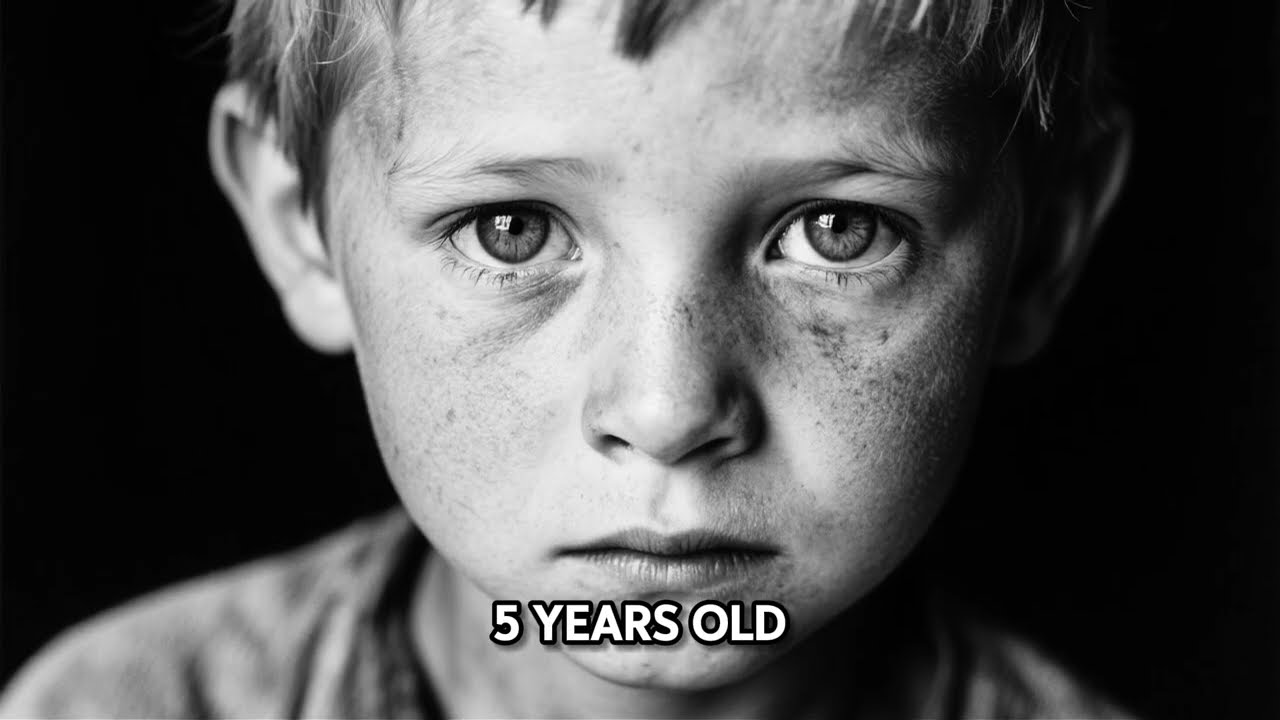

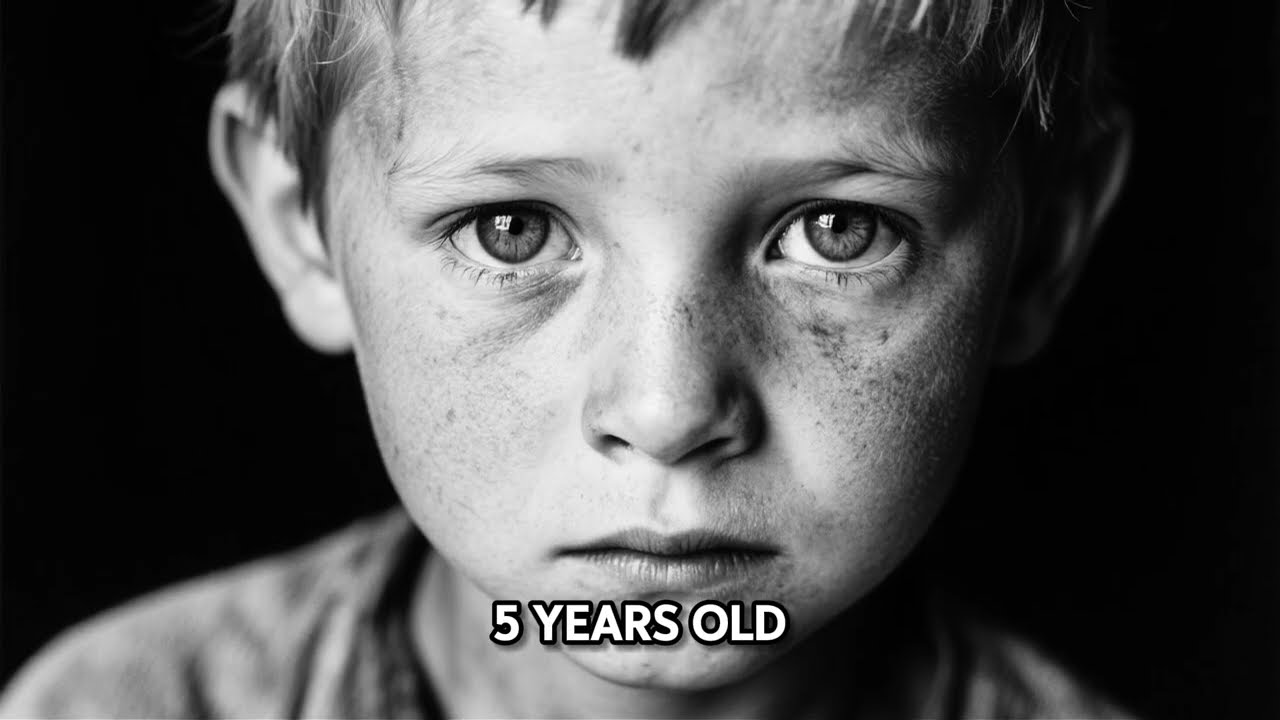

American Medics Found a 5 Year-Old German Boy Weighing Only 32 Pounds—What They Discover Shocks Them.NU.

American Medics Found a 5 Year-Old German Boy Weighing Only 32 Pounds—What They Discover Shocks Them

Is This Real?

A World War II story set in Bavaria, May 1945 (about 2,000 words), told in six short chapters

Chapter 1 — Mud, Canvas, and the End of a War

Bavaria in May did not look like victory.

Rain fell without drama, steady as breath, and turned a field outside Munich into a wide gray wound. Thirty canvas tents sagged under the weight of water. The ground became ankle-deep mud that clung to boots and stole each step. People moved slowly, as if the earth itself were trying to hold them down.

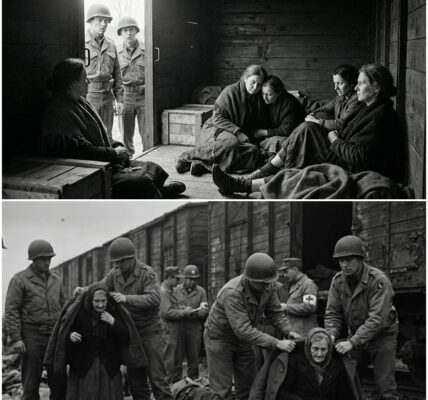

The war in Europe had ended only days earlier—Germany’s surrender announced like a door slamming shut. But the aftermath did not end when the guns did. It arrived in waves of displaced civilians: families pulling handcarts, widows with bundles, old men who stared too long at nothing, children with distended bellies and skin stretched thin over bone.

Corporal Daniel Morrison reported to the camp on May 12th. He was twenty-six, a medic from Oregon, and he had served with the 45th Infantry Division since North Africa. He had cleaned blood from his hands after patching up men who never woke. He had walked through villages where walls had been punched open by shells. He had learned to work quickly, to choose who could be saved when time and supplies ran short.

Yet nothing in combat medicine prepared him for the slow ruin of starvation.

Here there were no dramatic wounds to wrap, no obvious enemy to curse. There was only the long arithmetic of hunger: bodies consumed from the inside, immune systems failing quietly, children shrinking into silence. Morrison set up his screening station under a tent flap that snapped in the wet wind. He laid out his scale, tape measure, forms, and pencil, and began moving people through triage.

Critical: immediate hospital transfer.

Moderate: monitoring and supplemental feeding.

Stable: rations and shelter.

The categories felt too small for the suffering in front of him. Almost everyone belonged to all three, depending on the hour.

Still, he worked. That was what a medic did. He measured, asked, recorded, directed—trying to make order out of ruin with paper and routine.

On May 15th, in the afternoon line, he saw a child who made him stop breathing for a moment.

Chapter 2 — Thirty-Two Pounds

The boy stood beside an elderly woman who held his shoulder as if he might drift away. Morrison guessed the child was five, maybe six. Malnutrition made age uncertain—some children looked older because hunger carved sharpness into their faces; others looked younger because it stole height and strength.

This boy looked like absence.

His clothes hung loose on a frame too thin to fill them. His ribs showed through skin that looked almost translucent. His legs were narrow as kindling. His eyes seemed enormous, not because they were large, but because everything else had shrunk around them.

When they reached the table, Morrison spoke German with the steady tone he used to keep fear from spreading.

“Name?”

The woman answered, voice tired but firm. “Kurt Hoffmann. Five years old. My grandson.”

Morrison helped the boy onto the scale, careful as if he were lifting something fragile.

Thirty-two pounds.

A healthy five-year-old should weigh forty-five, maybe fifty. This child had lost nearly a third of what his body needed. Hunger had been eating him like a quiet animal.

Morrison measured height—three feet, four inches. Not stunted. That suggested the worst malnutrition was recent, the past months rather than a lifetime. Something had happened in the last year that had pushed him over an edge.

“When did he last eat properly?” Morrison asked.

The grandmother’s face tightened. “November. Maybe December. Our city was bombed. We fled east, then west again. After that…” She lifted a hand, helpless. “There was nothing. Roots. Sometimes bread when we could beg. Sometimes nothing.”

Morrison examined Kurt more closely: bleeding gums that hinted at vitamin deficiency, hair thinning, skin infections from a weakened immune system. The beginnings of rickets in the legs. A catalog of deprivation written in small symptoms.

“He needs hospitalization,” Morrison said. “Immediately.”

The grandmother nodded as if she had been waiting for someone to finally name what she already feared. “He doesn’t complain,” she whispered. “He hasn’t spoken much for weeks. He just… exists.”

Morrison felt a twist in his chest that surprised him. He had seen death often enough to keep his face calm. But this was different. This was a child who should have been dirty-kneed and laughing, hoarse from shouting at play. Instead he stood with the stillness of a person who had learned that movement costs calories.

Morrison reached into his bag and pulled out something small and ordinary by American standards—something the Army issued in huge quantities and soldiers traded like currency.

A chocolate bar.

He kept them for moments when medicine needed help from mercy, when a human gesture could reach places a bandage couldn’t.

He held it out.

“For you,” he said gently in German. “It will help you get stronger.”

Kurt stared at it. Not with excitement. Not even with simple hunger.

With caution.

With disbelief.

And then, with hands trembling from weakness, he reached out and took it as if it might break.

Chapter 3 — Three Words

Kurt did not tear into the wrapper. He held the bar against his palm, feeling its weight, as if trying to decide whether it belonged to the world he had survived.

Then he looked up at Morrison—direct, unblinking—and spoke in broken English, three words that stopped Morrison’s hands mid-motion.

“Is this real?”

The question was so small it should have vanished in the noise of the camp. But it landed like a blow.

Kurt wasn’t asking whether it was truly chocolate rather than some substitute. He was asking whether this moment belonged to reality at all: an American soldier kneeling in the mud, offering food to a starving German child with no demand attached.

He was asking whether kindness could still exist after months of a world that had taught him the opposite.

Morrison felt his throat tighten. He had spent three years building a medic’s armor—professional detachment that allowed him to keep working when grief tried to pull him under. He had watched young men die, had written names on tags, had carried bodies to trucks. He had done all of it without breaking.

But this question cracked something anyway.

Because it was not simply a child’s doubt.

It was evidence of what war had done—how thoroughly it had broken trust, how deeply it had taught a five-year-old to question goodness as if goodness were a trick.

“Yes,” Morrison said, voice rougher than he intended. “It’s real. You can eat it. It’s yours.”

Kurt glanced at his grandmother, seeking permission in her eyes, confirmation that accepting a gift was allowed in this strange new world. Her face crumpled and tears slid down the lines of her cheeks.

She nodded.

Kurt unwrapped the chocolate slowly. He broke off a piece the size of a coin and placed it on his tongue.

For a moment his expression changed—pure sensory astonishment. Sugar and fat and cocoa, tastes his body had been denied for months, moved through him like a bright shock. He chewed slowly, as if rushing would waste the miracle.

Then he rewrapped the rest carefully and pressed it to his chest.

Not hoarding greedily—protecting it.

Morrison looked away for a moment, blinking hard. He forced himself to breathe, to return to his checklist, because the line behind Kurt still needed screening and the camp still needed order. But his hands moved differently now, as if the boy’s question had reached into him and rearranged something.

He marked Kurt’s file: CRITICAL. Immediate transfer to the field hospital.

When the grandmother asked, barely audible, “He’ll be okay?” Morrison answered with the best truth he had.

“We’ll do everything we can,” he said. “He’s young. He can recover if we’re careful.”

He watched them walk away through the mud—an old woman supporting a skeletal boy who clutched chocolate like a piece of proof.

And when they disappeared into the gray, Morrison sat for a moment longer than the schedule allowed.

He kept hearing the words.

Is this real?

Chapter 4 — The School Turned Hospital

That evening Kurt was transferred by ambulance to a field hospital in a converted school building. Morrison went with the transport—officially to document transfers, unofficially because he could not let the story end at a checkbox.

Classrooms had become wards. The gymnasium smelled of disinfectant and exhaustion. Nurses moved with practiced speed, their faces tired but focused. War had ended, but the work of saving people had not. It had simply changed targets.

Captain Sarah Chun met them at intake. She was thirty-four, a chief pediatric nurse—calm, efficient, trained at Johns Hopkins before volunteering for the Army Nurse Corps. Her voice carried authority without cruelty, the kind of steadiness that makes frightened people believe in order again.

“How much does he weigh?” she asked.

“Thirty-two pounds,” Morrison said. “Five years old. Severe malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies.”

Chun’s eyes flicked over Kurt’s limbs, his face, the way he sat quietly holding the chocolate bar as if it were part of him. Her professional mask slipped a fraction.

“We start glucose to stabilize,” she said briskly, making notes. “Then gradual refeeding. Small amounts every two hours. Monitor electrolytes. Watch for refeeding syndrome.”

When Morrison told her what Kurt had asked—Is this real?—Chun paused with her pen suspended. She looked up, reading Morrison’s face as much as the words.

She knelt beside the gurney and spoke German with competent clarity.

“Hello, Kurt. I’m Nurse Chun. You’re safe here. We’re going to help you.”

Kurt stared, eyes huge, testing her tone for deception.

He whispered again, as if the question was now part of him. “Is this real?”

Chun answered firmly, with the kind of certainty children borrow when their own is gone. “Yes. This is real. You are in a hospital. We will take care of you.”

Kurt broke off another small piece of chocolate and ate it. Slowly. Carefully.

The refeeding began with almost insulting portions: broth, a few spoonfuls of mashed potatoes, soft bread. To an observer it looked like cruelty, feeding a starving child so little. But Chun knew what Morrison also knew: a body that has been starving can die from sudden abundance. Refeeding syndrome could stop a heart. Mercy required patience.

The nurses fed Kurt like you feed a fragile flame—small, steady, protected from sudden gusts.

Morrison visited daily. He brought small gifts when he could: a wooden toy soldier carved by a German prisoner, a picture book salvaged from the school’s damaged library, another chocolate bar rationed into tiny daily pieces.

On the third day Kurt finally asked a new question.

“Where is Ma?” he whispered.

“Your grandmother?” Morrison said. “She’s at the camp. She visits twice a day.”

Kurt absorbed this, then asked, voice anxious: “Will she get food too? Is she… real too?”

Morrison swallowed hard. “Yes,” he said. “She’s getting meals. She’s safe.”

Kurt nodded, and a visible tension left his shoulders. The confirmation mattered more than his own comfort. Even in starvation, he worried for her first.

Chapter 5 — Learning to Trust “Better Real”

As Kurt’s weight rose—thirty-two to thirty-five to forty-one pounds—his body began to remember how to function. His gums improved. His skin infections eased. His eyes grew less glassy. He slept longer stretches.

But the deeper injury was harder to measure.

He checked obsessively for meals. He hid bread under his pillow at first. He watched nurses with the wary attention of someone who had learned adults could fail.

Captain Chun requested a consultation with Dr. Robert Klein, a psychiatrist documenting war trauma among civilians. Klein interviewed Kurt through a translator and assembled the story: a father drafted and never returned, a mother killed in a bombing raid, months of running and begging, winter walks with no destination, other children dying along the road, adults stealing food from each other, abandoning the weak.

Klein explained it to Morrison with quiet precision.

“He learned the world is unsafe,” Klein said. “Food is scarce. Promises fail. So when you offered chocolate, it didn’t fit his reality. He needed to know whether he was hallucinating or being tricked.”

“Can he recover?” Morrison asked. “Not just physically.”

Klein considered. “Children are resilient. If he gets consistent safety—reliable care, predictable meals—his mind can rebuild trust. But he won’t forget.”

Weeks passed. Kurt began to speak more. He built towers from wooden blocks, then dismantled them, then rebuilt—practice, perhaps, in making a world that could be controlled. Morrison folded paper airplanes with him, and Kurt watched them glide across the ward with a quiet delight that looked almost like surprise at joy itself.

The hoarding faded. He stopped hiding bread. He still looked anxious when food was delayed, but he no longer treated every meal as the last.

One afternoon, Kurt smiled—small and cautious, but unmistakable. A nurse had made a silly face, and for a moment Kurt allowed himself to be five years old again.

Those small smiles felt like victories. Not for America, not for the Army, but for civilization itself—the proof that a child could return from the edge.

Before discharge, Dr. Klein asked Kurt a question as carefully as a doctor tests a wound.

“Is this real?” Klein asked. “The hospital, the food, the care. Is it real?”

Kurt thought hard, then answered in German.

“Yes. It is real. But it is strange real—different from before.”

“How is it different?” Klein asked.

“Before real,” Kurt said slowly, “was always afraid. Always hungry. Always moving. Never safe.” He paused, choosing words with the seriousness of a child who has had to become older than his years. “This real has food every day. Has bed that doesn’t move. Has people who say they help and then they help. It is better real… but strange because I remember other real.”

Klein wrote it down, his expression thoughtful. “That’s a brave thing to understand,” he told Kurt. “To remember the bad and still accept the good.”

Kurt looked up. “Will you remember me?”

“Yes,” Klein said. “I will remember you.”

Chapter 6 — A Chocolate Bar That Outlived the War

Kurt was discharged on May 30th and returned to the refugee camp with his grandmother. Morrison escorted him back—part duty, part something more personal. The boy carried a small suitcase of donated clothes and a handful of treasures: the wooden soldier, the picture book, saved chocolate bars.

As the supply truck bounced along muddy roads, Morrison asked gently, “Do you remember when you first came here?”

Kurt nodded. “I thought maybe I die,” he said simply. “Like other children.”

Morrison let the words sit between them. Then Kurt looked at him and asked, with the directness of someone who still needed logic for mercy.

“Why did you help?”

Morrison searched for an answer that a child could hold without it breaking.

“Because you needed help,” he said. “And we could help. That’s enough.”

Kurt considered. “In my before real, people not help unless they want something. Unless it is useful.” He looked out at the tents, the muddy field, the lines of people waiting for rations. “This new real… people help because helping is good?”

“Yes,” Morrison said. “Helping is good.”

At the camp, Kurt’s grandmother waited outside her assigned tent. When she saw Kurt stronger—still thin, but alive in a way he hadn’t been—she began to cry. Kurt ran to her and pressed himself against her with a sudden, fierce need to belong. They held each other, rocking in the rain.

Morrison stood back, giving them privacy, feeling the familiar tightness in his chest.

In July his unit was transferred. Before leaving Bavaria, Morrison visited one last time and gave Kurt a small stuffed bear another soldier had been discarding.

“For you,” Morrison said. “To remember.”

Kurt took it carefully, as reverently as he had taken the first chocolate bar.

“I will remember,” he said. “I will remember the American soldier who gave me chocolate and said it was real.”

Morrison returned to Oregon after the war. He built a life—marriage, children, work. But he kept the memory of a muddy camp outside Munich and a boy who asked if kindness was real.

Decades later, in 1983, a letter arrived forwarded through veterans’ organizations. It was from Kurt Hoffmann, now a grown man, a civil engineer in Hamburg.

He wrote: You saved my life, but more than that, you taught me that reality can include kindness. I built things because you showed me a world worth building.

Morrison read the letter three times, tears running down his face.

When his wife found him at the kitchen table, he held the paper as if it were fragile evidence.

“What is it?” she asked.

“A letter,” Morrison said quietly. “From a boy I helped during the war.” He swallowed. “I gave him chocolate… and told him it was real.”

And somewhere in Germany, long after uniforms and borders changed, Kurt kept a worn stuffed bear and a carefully preserved chocolate wrapper dated 1945—labeled in his handwriting:

Evidence that reality can be kind.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.