‘My Husband Will Kill Me for Surrendering’ —German Woman POW Refused Liberation ,Promised Protection.NU

‘My Husband Will Kill Me for Surrendering’ —German Woman POW Refused Liberation ,Promised Protection

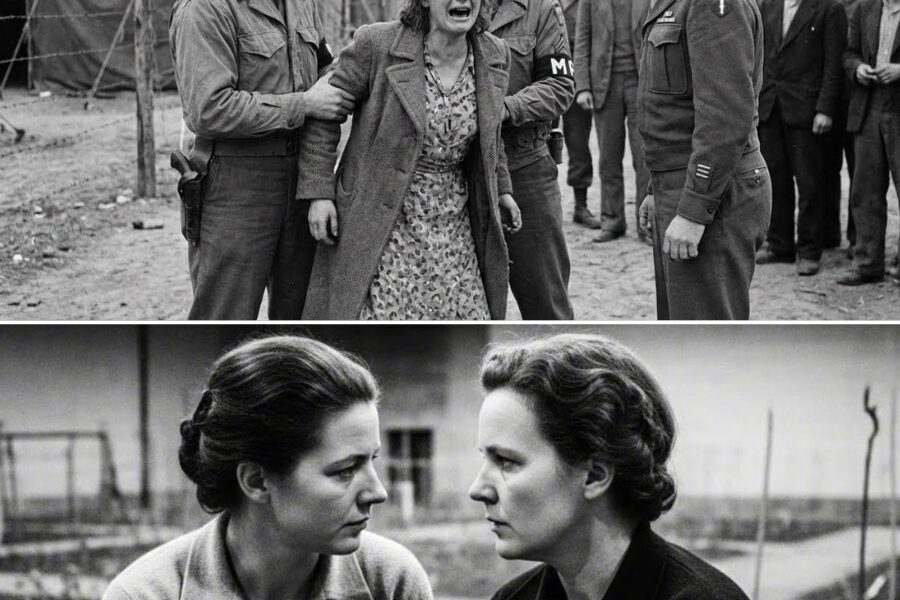

Part 1 — The Woman Who Refused Liberation

May 1945. Outside Munich.

The gates of the women’s prison camp opened with a sound that should’ve ended the story.

Metal groaned. Chains rattled. Someone shouted in German, then in English, then in something half-formed between the two—orders and relief all mixed together.

American soldiers stood at the entrance, rifles slung low, faces tight with the strange expression men wear when they’re walking into the aftermath of human suffering. They had seen camps before. They knew what they were likely to find.

What they didn’t expect was this:

When the women rushed toward the open gates—crying, laughing, collapsing into each other’s arms—one woman stayed behind.

She didn’t stumble.

She wasn’t delirious.

She wasn’t frozen from shock the way survivors sometimes are when their brains can’t process the word free.

She was sitting on her bunk, spine straight, hands folded in her lap as if she were waiting for a sentence.

Her name was Margaret Klene.

And while her fellow prisoners ran toward daylight, Margaret stared at the floor as if daylight was a trap.

A young American lieutenant approached her cell.

He was barely twenty-three. His uniform was dusty. His eyes were kind in the careful way young officers learn to be kind—like they know kindness is powerful but they’ve also learned it can get you hurt.

He spoke through a translator, a German-American sergeant who looked uncomfortable delivering joy in a language that had carried so much fear.

“Ma’am,” the sergeant said gently. “It’s time to go. The war is over. Germany has surrendered. You’re free.”

Margaret lifted her head slowly.

She looked the lieutenant in the eyes.

And in broken English, she said the sentence that changed everything:

“My husband will kill me if I go home.”

The lieutenant blinked. He thought he’d misheard.

The translator repeated it in German, then back in English, voice tightening.

Margaret’s mouth didn’t shake, but her hands did.

“He is SS,” she added. “He say… any wife who surrender is traitor.”

Behind the lieutenant, the camp yard was chaos—women being processed, names being recorded, Red Cross packages handed out, people sobbing into bread and soap like those objects were miracles.

Inside this cell, the war hadn’t ended.

It had simply changed shape.

Margaret didn’t need a promise about food or transport or paperwork.

She needed something else:

The right to choose a life that wasn’t waiting for her at home.

And she needed someone—anyone—with power to believe her.

Because for years, nobody had.

This is the story of how captivity became freedom, and how the enemy became her protector.

The Husband Who Called Fear “Honor”

March 1943.

A train carrying Margaret and forty other women rattled through the German countryside heading west toward France. Margaret pressed her face against the cold glass, watching villages blur past—each one looking more tired than the last, each one wearing the war like a sickness.

Margaret was twenty-six.

She was being sent to work in a munitions factory near Paris.

Her husband told her it was an honor.

An honor to serve the Reich.

Heinrich Klene, her husband of four years, was SS—stationed on the Eastern Front. When he left, he had gripped her shoulders hard enough to bruise.

“You will work for Germany,” he told her. “You will not shame me.”

His fingers pressed deeper.

“If the Allies come, you fight. You never surrender. Surrender is for cowards and traitors.”

Margaret didn’t speak. She didn’t argue. She had learned what arguing cost.

He leaned in close, voice dropping into something intimate and poisonous.

“Do you understand what happens to traitors?”

Margaret understood.

He had shown her.

Photos he kept in his desk drawer—people hanging from lamp posts, signs around their necks: traitor.

He showed them to her with pride, explaining how the Party dealt with weakness.

On the train, Margaret touched the place on her shoulders where bruises had faded from purple to yellow-green.

Around her, other women talked nervously about factory work, about Paris, about whether they would receive letters from home.

Margaret said nothing.

Silence was safer than words.

France: Work, Bombs, and the Threat That Never Left

The factory outside Paris was massive, concrete, surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. The women were housed in a converted warehouse, sleeping on thin mattresses laid in rows.

Twelve-hour shifts assembling shells.

Metal dust in the air.

Chemical smells that clung to skin.

Margaret’s hands, once soft from being a shopkeeper’s daughter, became rough and scarred.

But the work wasn’t what terrified her most.

It was the bombing raids.

Every few weeks, sirens screamed and the women huddled in basements while explosions shook the world above them. Supervisors told them the Allies were murderers who wanted to kill German women.

Heinrich said the same thing in letters when he bothered to write.

“If they capture you,” he wrote once, “they will do unspeakable things. Better to die fighting than fall into their hands.”

By June 1944, bombings increased. News filtered through: the Allies had landed in Normandy. Supervisors grew harsher, demanding longer hours, threatening anyone who slowed down.

Then one morning in August, the factory manager announced evacuation.

The Allies were getting too close.

They loaded the women onto trucks and drove them east toward Germany.

But Germany was not the Germany Margaret had left.

Cities were damaged. Roads were crowded. Fear was everywhere.

The convoy was attacked from the air. Two women died. They were buried in a roadside grave because war doesn’t pause for funerals.

Eventually, they arrived at a converted prison near Munich.

Thick stone walls. Cold corridors. Cells packed with women. Three to a cell. Straw mattresses. Thin blankets.

Margaret was assigned to Cell 47 with two other women:

Anna, quiet, from Hamburg.

Elsa, sharp-tongued, a former nurse.

At first they barely spoke. Trust was dangerous. Anyone could be reporting.

But as winter set in and news grew worse, defenses cracked.

One night, frost formed on the inside of their window and Elsa whispered:

“Do you think we’ll survive this?”

Anna shook her head.

“Does it matter? What is there to survive for?”

Margaret surprised herself by speaking.

“I hope we lose.”

The words landed like a gunshot in the darkness.

Elsa stared.

“You could be shot for saying that.”

“I know,” Margaret said. “But it’s true.”

“If we win,” she continued, voice quiet, “nothing changes. If we lose…”

She didn’t finish.

Anna did, flat.

“If we lose, we’re defeated.”

Margaret swallowed.

“If we lose,” she said slowly, “maybe some of us get to be free.”

That was the first time Margaret admitted out loud what she had been thinking for years:

Her country’s victory would lock her life into a cage forever.

Defeat—terrible, humiliating defeat—might open a door.

April 1945: The Guards Fade Away

In April, the prison began to fray.

First guards disappeared. Then more. Food deliveries became irregular. The women waited in their cells listening to distant artillery that grew louder each day.

Some whispered the Americans were coming.

Others said the Russians.

No one knew what would happen to women trapped in a prison while an empire collapsed around them.

Then, on May 3rd, the sound stopped.

A heavy silence fell.

And in early morning light, the gates opened and American soldiers walked in.

The lieutenant was young. Kind eyes. Dirt on his uniform. A German-American translator beside him delivering the news.

“Ladies,” the translator said, “the war is over. Germany has surrendered. You are free to go.”

Chaos erupted.

Women screamed. Wept. Collapsed. Laughed hysterically. Some stood frozen, unable to process the word free.

Anna grabbed Margaret’s hand. Elsa sobbed with her face in her sleeve.

Margaret felt ice move through her veins.

Free to go.

Free to go where?

Home.

Home to Heinrich.

Home to the man who promised to kill her if she surrendered.

For Germany, the war had ended.

For Margaret, her personal war was just beginning.

The Americans set up release tables in the yard, recording names and home addresses, handing out Red Cross packages with food and soap, organizing transport.

Women lined up eagerly, clutching their meager belongings, desperate to find families, rebuild lives.

Margaret stayed in Cell 47 watching through the barred window.

Anna turned.

“Aren’t you coming?”

“No.”

Anna blinked. “What do you mean, no? We’re free.”

“I can’t go home,” Margaret said.

Elsa stopped packing.

“Why not?”

Margaret’s voice stayed steady, but her hands shook.

“Because my husband is SS,” she said. “Because he told me surrender is treason. Because if I go home, he will kill me.”

The cell went quiet.

Anna’s eyes widened.

“He showed me pictures,” Margaret added softly. “What they do to women they call traitors.”

Elsa sat down hard on the bunk.

“My God,” Elsa whispered. “What will you do?”

“Stay here,” Margaret said. “Until I know it’s safe.”

Anna shook her head. “They’ll make you leave.”

“Then I will tell them the truth.”

The Question That Changed the Lieutenant

By midday, most women were processed and transported.

The yard that had been a storm of emotion in the morning grew quiet.

The Americans were packing up their tables when the young lieutenant noticed that Cell 47 still had one occupant.

He climbed the stone stairs with the translator, boots echoing in the corridor.

Margaret sat on her bunk like she was waiting for judgment.

The translator spoke gently.

“It’s time to go. Everyone else has left.”

Margaret shook her head.

“I cannot leave.”

The lieutenant frowned.

The translator asked, “Why not? You’re free. Don’t you want to go home?”

Margaret forced the words out in broken English, with the translator filling gaps.

“My husband is SS. He will kill me. He said surrender is treason.”

The lieutenant’s expression changed—confusion to shock to anger.

Not at Margaret.

At the man she described.

He spoke quickly in English. The translator looked uncomfortable, then turned back.

“Ma’am,” he said, “we need to consult a superior officer. Can you wait here?”

Margaret looked around the cell.

“I have nowhere else to go,” she said.

A Different Kind of Captain

Three hours later, a different American arrived.

Captain Robert Morrison—older, around forty, gray at his temples, eyes tired in the way men get tired when they’ve seen too much war.

This time they brought a female translator, Freda—a German woman who immigrated to America before the war.

Morrison sat across from Margaret in the administrative office.

“Mrs. Klene,” he said through Freda, “I need you to tell me everything from the beginning.”

And Margaret did.

Not only the parts she’d shared.

The parts she’d kept buried.

How Heinrich courted her when she was eighteen, charming at first. How he changed after marriage—controlling, violent. How ideology fed that violence, how the uniform made him worse. How he punished her for questioning him. How he used fear like a leash.

Freda’s pencil slowed as she listened.

Margaret’s voice cracked only once.

“He arranged the factory assignment,” she said. “He said I needed to be useful. If I was not useful to the Reich, I was not useful to him.”

Morrison leaned back, processing.

“And you believe if you return home, he will kill you.”

Margaret didn’t hesitate.

“I know.”

Freda stopped writing for a moment and looked at Margaret with wet eyes.

“I believe you,” she said quietly in German—off the record.

Then Morrison stood.

“Mrs. Klene,” he said, “I’m going to make some calls. In the meantime, you can stay here.”

He paused, then added the kind of sentence Margaret had not heard from a man with authority in years:

“You will eat. You will sleep. You will be safe while we figure this out.”

That night, Margaret sat in an empty dining hall eating American rations that tasted better than anything she’d eaten in years.

A young private brought her coffee and smiled kindly.

Through Freda he said, “Don’t worry, ma’am. Captain Morrison is a good man. He’ll help you.”

Margaret stared into the coffee.

She had learned not to trust promises.

Not from men.

Not from anyone.

But for the first time, she felt something unfamiliar:

Not trust.

Not yet.

A pause in fear.

Part 2 — The Calls Captain Morrison Made

The Americans didn’t throw Margaret out.

That alone felt unreal.

For years, “authority” had meant one thing to her: control. Threats. Punishment disguised as righteousness. A uniform that could do whatever it wanted because the system behind it approved.

Now a man in an American uniform—Captain Robert Morrison—looked at her fear and treated it like information instead of weakness.

He made calls.

He asked questions.

He didn’t laugh.

He didn’t tell her she was being dramatic.

He didn’t say, That’s your husband, you should go home.

He said, in effect: We will find out what’s true, and then we’ll decide what safety looks like.

Margaret had never heard a man with power talk like that.

It was almost harder to accept than cruelty. Cruelty makes sense when you’ve lived in it long enough. Kindness makes you suspicious.

For the first two days, Margaret stayed inside the prison that had turned into an American administrative site overnight. She was given a private cell, clean sheets, and three meals a day. She was not treated like a criminal.

She was treated like a person in danger.

But danger is stubborn. It follows you in your imagination when it can’t reach you physically. At night Margaret still woke in jolts, convinced she heard Heinrich’s boots in the corridor. She would sit upright in bed, heart racing, mouth dry, waiting for the door to fly open.

It never did.

The silence that followed was its own kind of lesson:

Sometimes the monster isn’t in the room anymore.

Sometimes it’s in your body.

Freda—Margaret’s translator—stayed close. Officially, she was there to interpret. Unofficially, she became something more: a calm presence, a German voice inside an American operation, someone who understood the cultural fear Margaret carried and didn’t dismiss it.

Freda’s German wasn’t the stiff military German Margaret was used to hearing.

It was softer. Human. The kind you hear in kitchens and train stations.

That mattered.

Because it told Margaret: you’re not alone in your language.

Captain Morrison visited daily.

Always with Freda.

Always calm.

Always asking the same core question in different forms:

What do you need to be safe?

Not what do you want.

Not what is convenient.

Safe.

Margaret answered carefully.

She had learned to speak like a person who expects her words to be used against her.

“My parents are dead,” she said.

“My brother died at Stalingrad.”

“Heinrich’s family disowned me.”

“Friends…” She hesitated. “He chased them away.”

Every answer closed another door.

Morrison’s face didn’t change.

He simply wrote things down and kept asking.

“What unit was your husband in?” he asked one afternoon.

Margaret swallowed.

“The Third SS Panzer Division,” she said. “He was proud of it. Too proud.”

Morrison wrote it down.

“Where was he stationed?”

“The Eastern Front.”

“Rank?”

Margaret hesitated a fraction.

“He was very proud of rank,” she said quietly. “He wore uniform even… even at home.”

Freda’s pen slowed.

Morrison’s eyes lifted briefly, not judgmental—just registering the depth of control Heinrich had exerted.

“Alright,” Morrison said. “We’re checking lists.”

Margaret’s stomach tightened.

Lists meant paperwork.

Paperwork meant truth.

Truth meant consequences.

And she didn’t know which consequence she feared more.

The Waiting

The waiting was agony.

Part of Margaret hoped Heinrich was dead.

The thought made her feel guilty, and then the guilt made her feel angry, because guilt was another chain Heinrich had wrapped around her.

But the truth was simple:

His death would mean freedom.

That didn’t make her evil.

It made her honest.

Another part of her—conditioned by years of fear—kept expecting him to appear anyway.

To storm into the prison.

To drag her out by the hair.

To tell the Americans they had no right.

To remind her that no matter what country won the war, he still owned her.

That was how he had trained her mind.

Not with logic.

With repetition.

On the third day, Morrison came in with a folder.

He didn’t sit immediately. He stood for a moment as if deciding how to say what he had learned.

Margaret’s hands tightened around her tin cup of coffee.

Freda sat beside her, face serious.

“Mrs. Klene,” Morrison said through Freda, “we have located your husband.”

Margaret’s heart stopped so hard she felt lightheaded.

Her hands gripped the edge of the table.

Alive or dead. Alive or dead.

Morrison’s next words landed like ice.

“He is alive.”

Margaret’s vision blurred. The room tilted. She realized she wasn’t breathing again.

Freda leaned in.

“Margaret,” she said softly in German. “Breathe.”

Morrison continued quickly, as if trying to anchor her before she fell.

“He is in American custody,” Morrison said. “A POW camp near Regensburg.”

Margaret’s body went numb.

Alive meant danger still existed in the world.

Alive meant he could come for her.

Alive meant her fear was not irrational, not imagined.

But Morrison said the sentence that steadied her just enough to keep her upright.

“He does not know you are here,” Morrison added. “And he will not know.”

Margaret stared at him.

Morrison’s voice stayed firm.

“We have also been investigating his record,” he said. “Mrs. Klene, your husband is being held for war crimes. He is not being released.”

“War crimes.” The words hung there.

Margaret had known Heinrich was cruel.

But war crimes?

What had he done?

Morrison didn’t give details. He couldn’t. He didn’t need to for the point to land.

“He is going to be tried,” Morrison said.

Margaret closed her eyes and felt nausea rise.

She had married a monster.

Not in the metaphorical sense she used in private nightmares.

In the literal sense.

A man whose cruelty was not a private flaw, but part of a system of murder.

She felt sick with shame and fury, and beneath it, something else—something she hadn’t allowed herself to feel yet.

Relief.

Because if Heinrich was in custody and facing trial, then the immediate threat of him killing her for surrendering was reduced.

Not erased—fear never erases cleanly—but reduced enough that her mind could start imagining the next day without his shadow.

Morrison watched her carefully.

“The question now,” he said, “is what you want to do.”

Margaret’s voice was small.

“I cannot stay here forever.”

“No,” Morrison agreed. “This facility is shutting down in two weeks.”

Margaret’s mouth went dry again.

“So where do I go?”

That was the real question.

She had no home.

No parents.

No brother.

No safe family network.

Germany was chaos. Hunger. Ruins. Men like Heinrich still existed everywhere even if her Heinrich was locked away.

Morrison spoke carefully.

“We are establishing displaced persons camps,” he said. “Temporary housing. Food. Medical care. And there are organizations helping women like you find work and start over.”

Margaret repeated the phrase like she didn’t trust it.

“Women like me.”

Freda leaned forward, eyes bright with purpose.

“I work with an organization,” Freda said. “We help women who are victims of abuse. Women who need to start over.”

Margaret stared at her.

“Find housing,” Freda continued. “Help you learn a trade. Maybe even help you leave Germany entirely if you want.”

“Leave Germany,” Margaret whispered, the words tasting forbidden.

Freda nodded.

“It is difficult,” she admitted. “But possible.”

Margaret felt something fragile rise inside her.

Hope.

Not the loud hope of propaganda.

Not the false hope Heinrich used when he wanted obedience.

A quiet hope that sounded like a question:

What if there is another life?

Freda’s Story

That afternoon, Freda stayed after Morrison left.

They sat in the prison yard where American soldiers had started a small garden—because soldiers always do that when the fighting stops. They plant things. They try to make the world sane again.

Freda spoke without melodrama.

“My sister married a man like your Heinrich,” she said.

Margaret turned her head.

Freda’s gaze stayed on the dirt.

“Brown shirt,” she said. “Very proud. Very correct in public.”

She paused.

“He hit her on their wedding night.”

Margaret felt her stomach twist with recognition.

“What happened?” she asked.

Freda’s voice stayed flat, like she had told this story too many times to let it hurt differently.

“She tried to leave him in 1938,” Freda said. “He found her. Beat her so badly she lost hearing in one ear.”

Margaret swallowed.

“The police did nothing,” Freda continued. “He was Party. She was just a wife.”

Freda’s hands clenched in her lap.

“She died in 1940. He said she fell down the stairs.”

She looked up then, eyes hard.

“Everyone knew he pushed her. Nothing happened to him.”

Margaret’s voice broke.

“I’m sorry.”

Freda shook her head sharply.

“Don’t be sorry,” she said. “Be angry.”

She gripped Margaret’s hand.

“Be angry enough to survive. Be angry enough to build a life he can’t touch.”

Margaret felt something shift.

For years, fear had defined her marriage.

Now fear had a companion.

Anger.

Not reckless anger.

Anger that gave her spine.

Anger that made her want to live out of spite if nothing else.

Anger that said: He doesn’t get to own my ending.

A Camp Full of People Starting Over

Captain Morrison arranged for Margaret’s transfer to a displaced persons camp near Stuttgart.

It was cleaner and more organized than she expected—rows of barracks, hundreds of people, former forced laborers, refugees, people whose homes were gone.

Everyone there was starting over.

That fact mattered.

It meant Margaret wasn’t a strange exception.

She was one of many.

She was assigned a bed, a small trunk, and three meals a day.

It wasn’t luxury.

But it was hers.

No Heinrich to judge her meals, her words, her body.

No threats hanging over her head.

Just space to breathe.

Margaret enrolled in English classes offered by aid organizations. She learned sewing and got work in the camp’s clothing repair shop.

She made friends with other women because women in survival situations do what men often don’t: they form small nets and pull each other through.

Some nights she still woke in panic, convinced Heinrich stood over her bed.

Other women had nightmares too.

They comforted each other without making speeches. A hand on a shoulder. A shared cup of weak tea. Silence that didn’t feel lonely.

But the hardest part wasn’t fear.

It was guilt.

Guilt for having believed pieces of propaganda.

Guilt for having complied to survive.

Guilt for having assembled shells in France.

Guilt for not questioning sooner.

She confessed it to Freda one day.

“How can I start over when I was part of it?” Margaret asked. “I helped make weapons.”

Freda’s answer didn’t erase guilt, but it did something important:

It reframed it.

“You were forced,” Freda said. “You survived by doing what you had to do.”

Margaret’s eyes filled.

“But I should have seen it sooner.”

Freda leaned closer.

“Maybe,” she said. “But you see it now.”

She tapped Margaret’s chest lightly.

“The question is what you do with what you see.”

That sentence stayed with Margaret.

Because it wasn’t forgiveness.

It was direction.

The Call About Heinrich

Months later, Morrison visited the DP camp on other business and stopped to see her. They sat with coffee and paperwork and the awkwardness of talking about a man who had shaped Margaret’s life by trying to destroy it.

Morrison told her Heinrich’s trial was scheduled.

He told her she would not be forced into anything.

But if she wanted to speak—about the kind of man he was, about what he believed, about what he did to her—there were avenues.

Margaret didn’t decide immediately.

She went back to her bunk and lay awake thinking about standing in a room with Heinrich again.

Part of her wanted to vanish.

Part of her wanted to speak.

The part that had grown stronger—the part that had begun to live—wanted to take back something he had stolen.

Not revenge.

Voice.

And when she finally chose, it wasn’t because she wanted to hurt him.

It was because she wanted to stop hiding.

The First Real Definition of Freedom

Margaret understood something in those months that she hadn’t understood on Liberation Day when everyone else ran to the gate:

Freedom isn’t the open door.

Freedom is what happens after you step through—if you can step through without being pulled back.

She had been afraid of leaving because leaving meant going back into Heinrich’s control.

The Americans didn’t force her into that.

They listened.

They investigated.

They protected.

And in doing so, they showed her a form of authority she had never experienced:

Protection without ownership.

Help without punishment.

Power used to give someone options instead of take them away.

That didn’t erase what she had lived through.

But it gave her something she hadn’t had since she was eighteen:

A future that belonged to her.

Part 3 — The Bravest Word She Ever Said

Margaret didn’t decide to speak against Heinrich in a single dramatic moment.

It wasn’t like the movies where a woman stands up in a courtroom, points at the monster, and suddenly everything inside her becomes steel.

Real fear doesn’t melt that cleanly.

It clings.

It echoes.

It follows you into sleep and makes your hands shake when you don’t understand why.

So Margaret took months.

Months of English lessons and sewing work and weak coffee in a displaced persons camp cafeteria. Months of waking up with her heart sprinting because her brain still expected Heinrich to be in the room. Months of hearing other women whisper stories that sounded different but felt the same—the same pattern of control, humiliation, threats.

And slowly, she noticed something:

Her fear was no longer the only thing defining her days.

There were stretches of time where she forgot to be afraid.

Not for long.

Not perfectly.

But enough.

Enough to prove her life could contain something besides survival.

It was during one of those stretches—one of those rare calm afternoons—that Margaret realized she had been living her entire marriage as if Heinrich owned her voice.

He didn’t just control where she went or what she said. He controlled what she believed was possible.

He had convinced her that speaking would lead to death.

Now he was in custody.

Now he was the one being watched.

Now the uniform that had protected him was gone.

And Margaret asked herself a question that felt almost dangerous to form:

If I don’t speak now, when will I ever?

The First Time She Said It Out Loud

Freda and Dr. Eleanor Wright—the British psychologist who rotated through the DP camp—helped Margaret prepare for the idea of facing Heinrich again.

They didn’t treat it like a heroic mission.

They treated it like trauma management.

What happens when you see him?

What happens when he looks at you?

What happens if you freeze?

Margaret hated those questions because they forced her to imagine the moment before it happened.

But the women helping her were practical.

They were trying to keep her safe.

Not physically—Heinrich couldn’t touch her now—but psychologically.

Remember, Dr. Wright told her gently, you have power now. He is the one in chains. He is the one being judged.

Margaret repeated that sentence like a prayer.

Power now.

She didn’t feel powerful.

She felt fragile.

But she also felt something else she hadn’t felt in years:

Anger that didn’t turn inward.

Anger that pointed outward like a compass.

Freda sat with her one evening and said the thing Margaret needed to hear from someone who understood Germany and understood what men like Heinrich did to women like her.

“You don’t owe him silence,” Freda said.

Margaret stared at her hands.

“I don’t want revenge,” Margaret whispered.

“I know,” Freda said. “This isn’t revenge. This is ownership.”

Margaret’s throat tightened.

“Ownership of what?”

Freda leaned in, eyes steady.

“Of your story,” she said. “He stole it. He stole your right to say what happened. You take it back.”

That was the moment Margaret understood something she hadn’t understood even when the prison gates opened.

Liberation was not the end of captivity.

Captivity ends when you stop living inside someone else’s fear.

Facing Him

When the time came—when she was finally transported to the courthouse under supervision, when she sat in a waiting room with her hands folded tightly in her lap—Margaret felt the old terror rise.

Not because she doubted what Heinrich had done.

Because her body remembered him.

Her body remembered how it felt to exist near him.

Freda sat beside her like a wall—quiet, solid, present.

“You can still change your mind,” Freda said softly.

Margaret shook her head.

“No,” she replied. “I need to do this. Not for him.”

She paused.

“For me. For all the women he hurt. For the women who couldn’t speak.”

Her voice didn’t shake on the last sentence.

That surprised her.

Then it was time.

Margaret walked into the room, and there he was.

Heinrich looked smaller than she remembered. Thinner. Stripped of his uniform, stripped of the posture it gave him.

His eyes were still hard, though. Hardness was his natural language.

When he saw her enter, his expression flickered—surprise, then rage, then something else.

Fear.

Margaret recognized it with a strange calm.

Good, she thought.

Let him be afraid for once.

Margaret spoke about what he had done to her.

Not with drama.

With clarity.

She described threats. Control. Violence. The way he used ideology like a weapon. The way he treated “surrender” like a crime.

She told the truth about what it meant to be married to a man who believed he had the right to destroy you if you disappointed him.

At one point, she looked directly at him and said the sentence that had started everything back in that prison cell.

“My husband would have killed me for surrendering.”

And in saying it out loud, in a place where people wrote it down, where it became record instead of secret, Margaret felt something loosen inside her.

Not joy.

Release.

The defense tried to shake her.

Tried to suggest she was bitter.

That she was exaggerating.

That she was emotional.

Margaret didn’t flinch.

Because she had lived years where flinching was survival. Now she understood something:

Calm truth is stronger than a man’s anger.

When she stepped down, her knees felt weak—not from fear, but from adrenaline draining out.

Freda gripped her hand.

“You did it,” Freda whispered.

Margaret nodded once.

She didn’t cry.

Not then.

She felt too empty to cry.

The Verdict

Heinrich was convicted.

Not solely because of Margaret—his crimes were larger than her marriage—but because the system that had protected him was gone, and now there were people documenting what men like him had done in the name of ideology.

He was sentenced to death.

Margaret felt no happiness at the sentence.

No celebration.

People expect victims to feel satisfied when their abuser falls.

But abusers don’t leave cleanly.

They leave damage.

His punishment didn’t erase what he had done.

It didn’t give her back the years.

It didn’t undo the fear that lived in her body.

It only did one thing, and that one thing mattered:

He couldn’t create new victims anymore.

Freda watched Margaret’s face carefully and asked, gently, “How do you feel?”

Margaret searched for words and found only one that fit.

“Tired,” she said.

It wasn’t a weakness.

It was honesty.

England

Freda’s organization had been working on Margaret’s case quietly, building the paperwork, finding options, because that’s how people survive after war: through forms and signatures and someone willing to push a file through a system that would rather forget.

They found her a sponsor in England—a family willing to help her immigrate, to offer her a job and a place to stay while she built her life.

“It won’t be easy,” Freda warned. “You’ll be a German in England right after the war. Some people will be kind.”

She paused.

“Others won’t.”

Margaret nodded.

“I understand,” she said.

Then she added, quietly but firmly:

“But I’ll be free.”

Before leaving, she returned to Munich one last time.

Not to her old apartment—someone else lived there now, and the past was not something she could reclaim like furniture.

She went to the cemetery where her parents were buried.

She stood with flowers in hand and whispered:

“I’m sorry.”

Sorry she married him.

Sorry she didn’t see what he was sooner.

Sorry for so many things.

Then she lifted her chin and said the sentence that mattered most.

“But I survived.”

“And I’m going to build something good from all this pain.”

“I promise.”

The ship to England departed from Hamburg.

Margaret stood on deck watching Germany shrink behind her—ruins and ghosts and a chapter she never wanted to reopen.

Part of her felt guilty for leaving.

Germany was her homeland.

But her homeland had offered her nothing but fear.

England was gray and cold when she arrived.

The sponsor family was kind but distant at first—polite, cautious, not sure what to do with a German woman whose story they only partially understood.

Margaret took a small room and a job in their office helping with paperwork.

At first, she was mostly invisible.

Which suited her.

Her English was imperfect.

People stared at her accent.

Some were hostile when they learned she was German.

Margaret kept working anyway.

Because work was the one thing she trusted.

And slowly, she built a life.

Friends.

A small apartment later.

A routine that didn’t involve waiting for a man’s mood.

A life where she could decorate a room without permission.

Where she could spend money without fear.

Where she could sleep without listening for boots.

She attended church sometimes, though she wasn’t sure what she believed anymore. The pastor—gentle, a former chaplain—listened without judgment.

“God doesn’t blame you for surviving,” he told her.

“And neither should you.”

The Letter That Finished It

Two years later, Margaret received a letter from Freda.

Heinrich had been executed.

It was over.

Truly over.

Margaret sat alone in her room holding the letter, waiting for relief to flood her.

It didn’t.

She felt no joy.

No triumph.

Just a deep, exhausted quiet.

His death didn’t heal scars.

It didn’t undo nightmares.

It simply meant he couldn’t make new ones.

Margaret wrote back:

“Thank you for telling me.”

“I feel strange. Not happy, not sad—just finished with that chapter.”

“I’m ready to write a new one now.”

And she did.

Turning Survival Into Help

Margaret began working with the charity office, helping other displaced women navigate paperwork, housing, and the complicated maze of starting over.

She learned to recognize abuse in the way survivors often do—not as a dramatic event, but as a pattern: isolation, control, fear disguised as “love” or “duty.”

When a young woman came in years later—German, shaking, fleeing an abusive marriage—Margaret sat with her and took her hand.

“I understand,” Margaret said simply.

“My husband was the same.”

The woman’s eyes filled with tears.

“How?” she whispered. “How did you escape?”

Margaret smiled, not because the memory was pleasant, but because it was true.

“I surrendered to the Americans,” she said.

“I asked for protection.”

“And they gave it.”

She paused, then added the line that became her quiet lesson to others:

“Not all enemies are enemies.”

“Sometimes the people you’re told to fear are the ones who save you.”

Margaret never remarried.

Trusting a man that deeply again felt impossible.

But she built a rich life anyway.

Work she believed in.

Friends.

Small joys: gardening, painting, laughter that came without permission.

And when she looked back on the moment in May 1945—the open gates, women running, her staying on the bunk—she finally understood what was true then and true now:

She wasn’t afraid of freedom.

She was afraid of going back into chains.

Real freedom came when someone heard her fear and said:

“We will keep you safe.”

That promise changed everything.

In later years, Margaret kept a diary.

One of her final entries carried the truth she wished she could have given her younger self:

“I spent years being told surrender was weakness.”

“That asking for help was shame.”

“That enemies could never be trusted.”

“But I learned that sometimes surrender is the bravest thing you can do.”

“Sometimes asking for help is the smartest choice.”

“Sometimes freedom is not the open gate.”

“It is the moment someone believes you.”

Margaret Klene died in 1987 at seventy, in a small London apartment.

She left behind paintings, letters, and a legacy of helping women find a life that belonged to them.

And that is the story worth remembering:

Not only that the war ended.

But that one woman finally got to choose what happened next.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.